Global Challenges to Democracy Report No.260

Party Like Mamdani

Debasish Roy Chowdhury

November 26, 2025

New York mayor-elect’s campaign masterclass has important lessons for India’s flailing democracy, particularly its ineffectual opposition parties that have failed to mount any meaningful pushback against Modi’s monopoly over power in more than a decade.

Contents

- Feeling the buzz from Brooklyn to Bihar

- Crisis of political parties

- Reading the ‘moment’

- A real alternative

Feeling the buzz from Brooklyn to Bihar

Zohran Mamdani has lit up social media in unusual places around the world far away from ground zero of his triumph. In India, a bit more than others. The Indian-born mayor-elect’s victory speech laced with quotes of India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Bollywood music has added to the buzz, but his desi connection is not the only reason why Mamdani resonates across three oceans.

Like people in democracies everywhere weighed down by populist demagogues and dispirited by sterile politics governed by big money and small men, Mamdani has inspired hope of a breakthrough in India as well. In fact, nowhere does the lessons of his success seem more urgently relevant than in India, which has gone from being the world’s largest democracy to an ‘electoral autocracy’ in a decade under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and the opposition has seemed ineffectual in mounting any substantive pushback. This month, Modi triumphed again as an opposition alliance was drubbed in the eastern Indian state of Bihar by a coalition formed by his Hindu supremacist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that swept the state election by winning an astounding 88 per cent of the seats in which it contested.

With this victory, Modi has again proved his lock on power is unchallenged and tamped down hopes of an opposition that briefly looked resurgent after last year’s national elections that returned Modi to power for a third term but with a lower margin. His legislative numbers in the national Parliament dipped a little as his party lost the absolute majority in Parliament for the first time, forcing it to seek outside support. But Modi’s dispensation has remained the country’s dominant political force by far, and just as unrelenting in its constitutional transgressions and programmatic targeting of minorities. The stunning Bihar election result now shows it has already put behind last year’s minor upset and is gaining more momentum, instead of being slowed by the burden of 10 years of incumbency.

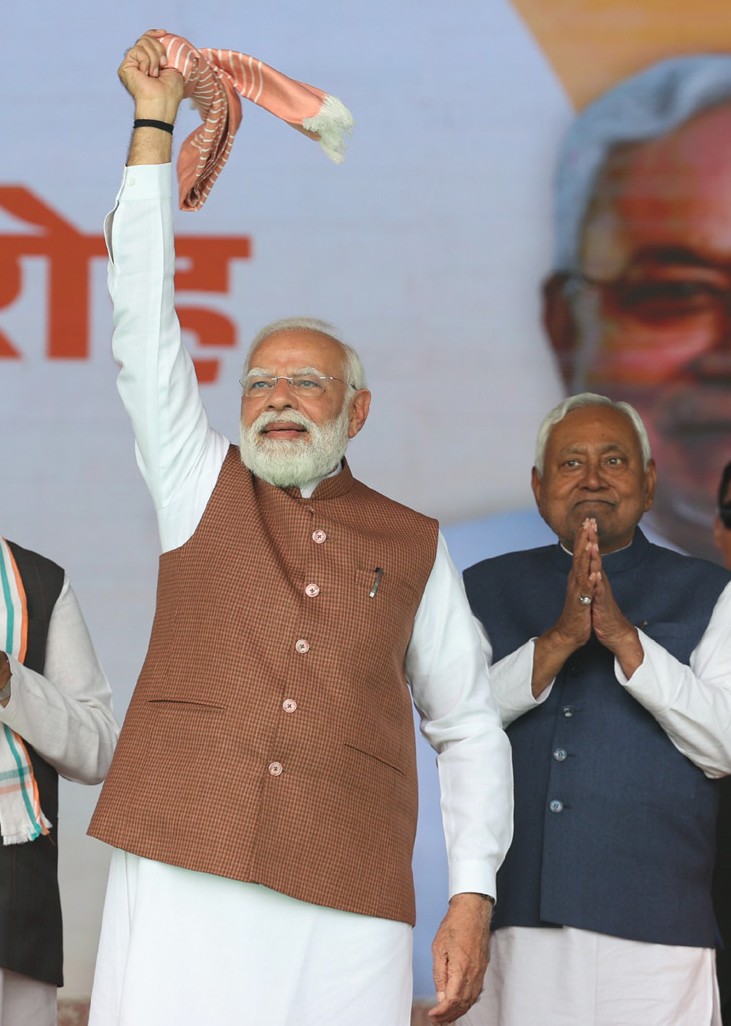

PM Modi attends the swearing-in-

ceremony of new Bihar government held

at Patna, in Bihar on November 20, 2025.

Image: Wiki Commons

Before Bihar, Modi’s BJP wrested back three states in recent local elections in the past year. In one state, Delhi, the top opposition leaders running the previous government were put away in jail, and in others, the opposition parties allege that his party won by manipulating voter rolls. A Brazilian model, whose photo appears for nearly two dozen voters with different names and addresses in the rolls, has become the unlikely face of the vote fraud row. But even with scandalous revelations such as these, the opposition parties have not been able to slow the juggernaut of the man the US right wing calls “a Trump before Trump”, as the Bihar result shows.

The Bihar election itself was held in the backdrop of a raging controversy over voter fraud as the opposition launched a movement against a voter verification exercise that it claimed was designed to remake the electoral rolls in a way that tilts the balance in favour of the BJP. These allegations are unprecedented as the sanctity of elections has never been questioned in India. But then, just as their ‘vote chori’ (vote theft) movement was gaining traction and their accusations against the country’s Election Commission were growing louder, the opposition parties suddenly shifted gears when the Bihar election dates were announced. They promptly joined the same election process officiated by the same set of Election Commission officials calling rigged, and negating their own claims of electoral wrongdoing, in the freshest sign of the rudderless opposition’s tactical and ideological incoherence.

Crisis of political parties

The stasis of India’s opposition parties is part of a global trend. As foundational institutions of democratic governance, political parties worldwide are experiencing organizational decay and popular disengagement, eroding their capacity for connecting citizens to the state and political processes.

Voter apathy, social media, personalization of politics, and decline of grassroots mobilizing wings like trade unions, are among the many factors that have contributed to this decay, rendering conventional parties powerless before demagogic politicians. Their loss of legitimacy has fostered the rise of polarizing authoritarians and bad-faith actors while fuelling public disillusionment and social unrest from Madagascar to Nepal, in what has come to be known as ‘Gen Z revolutions’.

Yet, compared to other democratic institutions, the role of party decay is far less understood or studied as a factor of democratic backsliding, even though political parties remain the primary site of pushback against illiberal forces. Democracy does not just die when the executive tames and hollows out the legislature, the judiciary and the media. They also perish when the opposition loses its vitality.

In India, the signs of party decay have long been evident: strong personalization, weak internal democracy, elite capture, and ideological stagnation. And, with Modi’s rise to national power in 2014, strategic confusion. Mamdani’s victory shows the potential of party rejuvenation through strategic clarity.

It begins with that awkward thing called principles, which we were told has no place in practical politics, but evidently, does.

Ideological rigidity, pundits would have us believe, is a liability in ‘moments’ when politics moves. Ever since the ascent of Modi and Trump, we have been told that India and the US have moved right—as if political mood is a homogenous monolith. Trump never commanded the support of more than a third of the electorate, and Modi, not more than a fourth, when factoring in the number of voters who abstained from voting along with their parties’ actual vote share, but such fallacies have taken root in political discourse. When opposition parties buy into such notions, they start to compromise on their core principles in the name of political expediency, and muddle their strategies.

If the US Democratic Party establishment’s reluctance to go all in on Mamdani till late in the campaign is a reflection of this pathology, in India it manifests in an opposition strategy that takes a certain amount of rightward shift in public mood as a given and a politics tailored to it. Traditional opposition parties, for example, have been hesitant in rallying staunchly behind Muslims against the state-led humiliation and brutalization of the community that has become commonplace, for the fear of being seen as pro-Muslim by the majority Hindus.

This misplaced political pragmatism is the reason why Muslim representation in legislatures has declined in India, as even ‘secular’ parties now hesitate to field Muslim candidates; Modi’s party rarely fields any.

Had Mamdani been in India, he would have no place in the BJP, and most certainly not be an opposition candidate for any high-profile office. And, if he attempted a political life outside of the atrophied opposition parties, he would be languishing in jail on trumped up charges, as many Muslim dissenters are.

Incidentally, Mamdani has expressed solidarity with their cause in far-away New York, reading out the prison diary of student activist Umar Khalid, who has been a political prisoner for five years in a Delhi jail without even a trial. India’s opposition leaders, on the other hand, won’t touch Khalid with a bargepole. The ‘moment’ wouldn’t let them.

Reading the 'moment'

Zohran Mamdani participates in 43rd

Annual Dominican Day Parade in

Manhattan, New York, on August 10, 2025.

Image: Lev Radin / shutterstock.com

Mamdani’s success underscores the power of upright politics in moments of supposed political shifts, a major learning point for oppositional politics in all beleaguered democracies. His defiant campaign in fact doubled down on everything that a pragmatically flexible electoral strategy would disavow—from his hard left policy prescription and pro-Palestine position to the unapologetic celebration of his own minority identity.

Misdiagnosis of political ‘moments’ stems from a common attribution error in the global rise of illiberalism. In Democracy Erodes from the Top: Leaders, Citizens, and the Challenge of Populism in Europe, political scientist Larry Bartels argues that populist demagogues are growing in Europe not necessarily because people frustrated by the failures of democracy are driven to despotic figures, but because conservative parties, once elected, capture institutions to entrench themselves in power. Bartels calls this “illiberalism by surprise”, as seen in Hungary and Poland in the past decade.

In Ordinary People in Extraordinary Times: The Citizenry and the Breakdown of Democracy, Nancy G. Bermeo examines the countries in 20th century Europe and Latin America where democracy broke down, and similarly concludes that it is the elites who break democracies, not the people. Polarization is often pinned on the people but people in reality do not change their political beliefs as wantonly as generally thought, she argues.

A recent study of 12 countries that have experienced democratic backsliding in recent years, including India and the US, shows voters do not consciously embrace antidemocratic alternatives out of frustration. They merely vote for change, as people are expected to do in a democracy.

Populist demagogues also do not campaign on promises of dismantling democracy; it’s only after they come to power that they begin to capture and cripple governing institutions. Modi’s campaign promise was inclusive growth and economic turnaround, not centralisation of power or state-led Islamophobia.

Mistaking a vote for a demagogue as a vote for illiberalism is thus a fundamental error of oppositional politics, common in both India and the US. In India, Modi and his party have done well not necessarily because his illiberalism appeals to the people, but also because many voters see them as more capable of governing than the alternative. They also come across as possessing a conviction in a specific vision for the country, as opposed to a flailing opposition without one and promising everything. The main opposition party in Bihar, for example, promised one government job for each of the 27 million families of Bihar—a campaign pledge verging on the ridiculous. Mamdani succeeded because, rather than second-guessing the popular mood and trying to sell a campaign to fit that mood, he focused on what he stands for, stuck to it, and relentlessly messaged it. He established that he is more capable of governing, that he has a vision, and a plan to execute it. The same moral appeal of his uncompromising belief system that attracted tens of thousands of young canvassers pounding the pavement for him also eventually drew in the voters.

A robust politics of principles is thus not only the best strategy to stand up to a populist authoritarian but also helps deepen popular engagement with politics itself at a time when people, especially the youth, across the world are growing disenchanted with it. Apart from reinvigorating a dazed and defensive party, Mamdani also got New York’s Gen Z to knock doors and initiate a million community conversations rather than burn buses. In sum, just being yourself is a terrific strategy. That’s an invaluable lesson for conventional political parties everywhere in an age of politics by consultants and professional strategists who have spawned a billion-dollar industry tailoring cosplays for political parties, making them ever more distant and disconnected.

A real alternative

Mamdani’s win also shows the power of an alternative vision of the country in concrete policy terms, instead of scaremongering about the incumbent and trafficking in fuzzy programmes or promises (like millions of non-existent government jobs). His message was less about Trump’s existential threat to democracy and more about exactly what he will do if elected mayor, and how. India’s opposition has spent much of the past decade doing the opposite.

It hasn’t worked, because studies in voter psychology show people in polarized electorates are willing to trade off democratic principles for partisan interests. Executive takeovers have accounted for four out of every five democratic breakdowns since the turn of the century as we have entered an era of creeping despotism by democratically elected incumbents rather than swift autocracies by military coups and the like.

The perpetuation of these despots in power has been possible partly because many voters place their leader above their democratic values. Droning on about the threats to democracy from an incumbent does not make any electoral difference if the people have concluded that democracy is the problem and the incumbent, the solution.

The more effective foil to polarizing despots is what Mamdani has done: find an alternative narrative through issue-based appeals to crowd out the identity-based stories voters have been fed, and message it effectively through grassroots mobilization. In the process, he has regenerated the centre, remade the electorate by bringing in new voters, forged new social coalitions, and contributed to what political scientists call ‘active depolarization’, by feeding and shaping a non-sectarian political identity.

Ravaged by a decade of divisive politics, India could use Mamdani’s blueprint of messaging and organizing to take on the polarizing demagogue whose narrative monopoly the country’s opposition parties have failed to dent in 10 years. Mamdani’s campaign masterclass offers them vital clues to transform India’s politics.

But they would have to transform themselves first.

Mamdani’s win highlights the importance of party mechanisms that create space for new talents and ideas even when they do not necessarily align with the party leadership. This is possible only when political parties have internal democracy—de rigueur for western democracies but noticeably absent in India parties, where power is highly centralized, often dynastic. There are hence no institutional mechanisms for filtering fresh ideas and spotting and promoting new political talent in India.

The bleak Bihar result has reinforced popular frustration with India’s inept opposition, especially the Congress party, the main national party whose growing irrelevance has left India without a viable alternative. But even before that, India’s liberal influencers and talking heads have been yearning for an Indian Zohran in their reels and tweets ever since the election result in New York, which landed a week before the one in Bihar.

There would be, probably many, Indian Zohrans if India’s political parties were half as earnest about democratizing themselves as they are about democratizing India. Then, New Delhi might also manage to reclaim democracy, like New York has.

The Author

DEBASISH ROY CHOWDHURY

Debasish Roy Chowdhury is a journalist, researcher and author based in Hong Kong. With John Keane, he has co-authored To Kill A Democracy: India’s Passage to Despotism (OUP/Pan Macmillan). Apart from Hong Kong, he has lived and worked in Calcutta, Sao Paulo, Hua Hin, Bangkok and Beijing, and reported from Malaysia, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Nepal and Qatar. He is a Jefferson Fellow and a recipient of multiple media prizes, including the Human Rights Press Award, the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA) award and the Hong Kong News Award. His recent writings are available at Muck Rack.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org