Peace and Security in Northeast Asia Policy Brief No.259

Reassurance on the Korean Peninsula: Lessons from Scholarship to Stabilize Deterrence

Reid Pauly

November 25, 2025

This policy brief reviews the lessons of academic scholarship on deterrence and assurance in order to unpack how and why tools of assurance work. In pursuit of stable deterrence on the Korean Peninsula, all parties ought to be reassuring one another. While there are trade-offs between communicating deterrence and reassuring adversaries, both are necessary for a stable relationship and reducing the probability of crisis or war. First, I offer definitions for key terms. Second, I review scholarly findings on credible communication and signalling. Third, I apply theory to the policy problem of stabilizing the Korean Peninsula.

Contents

- Abstract

- Definitions

- Scholarship on Credible Communication

- Stabilizing the Korean Peninsula

- Conclusion

Abstract

In pursuit of stable deterrence on the Korean Peninsula, all parties ought to be reassuring one another. While there are trade-offs between communicating deterrence and reassuring adversaries, both are necessary for a stable relationship and reducing the probability of crisis or war. To unpack how and why tools of assurance work, this paper reviews the lessons of academic scholarship on deterrence and assurance. First, I offer definitions for key terms. Second, I review scholarly findings on credible communication and signalling. Third, I apply theory to the policy problem of stabilizing the Korean Peninsula.

Key Takeaways:

- Reassurance need not replace deterrence, it is complementary

- Compellence can undermine deterrence; and denuclearization is a compellent goal

- Military signalling on the Korean Peninsula should support deterrence, not compellence

- Conventional arms control can send reassuring signals that stabilize deterrence

Definitions

THREE TYPES OF ASSURANCE

There are three types of ‘assurance’ in the study of international politics: reassurance of adversaries, coercive assurance, and ally reassurance. All three are relevant to the Korean Peninsula.

First, reassurance of an adversary is an attempt to communicate: “I mean you no harm.” Political scientist Janice Stein defines reassurance as “a set of strategies that adversaries can use to reduce the likelihood of resort to the threat or use of force.”[1] Ideally, reassurances mitigate the ‘security dilemma’—whereby countries tend to see each other’s defensive arming as offensively threatening. When reassured, they perceive each other as less threatening.

Second, ‘coercive assurance’ describes the conditional intentions communicated by one state to another in the context of coercion: “if you comply, I will not harm you.”[2] What makes assurance a unique dilemma in the context of coercion is the fact that the coercer intends to threaten the target. There is no connotation of “I mean you no harm” in coercive assurance; rather I am threatening you today and I need you to believe that I mean it. The coercer wishes to send two seemingly conflicting signals: that its threats are credible, just also contingent upon the target’s behaviour. The object is to present a choice—one that does not lead the target to believe they are ‘damned if they do, and damned if they don’t’.

Third, ally reassurance is a promise to come to the aid of an ally: “I will defend you.” While crucial to US–ROK relations, it is not the focus of this paper. That one’s allies need reassurance is well known to policymakers—so well, in fact, that it often leaves the other two types of assurance underappreciated.

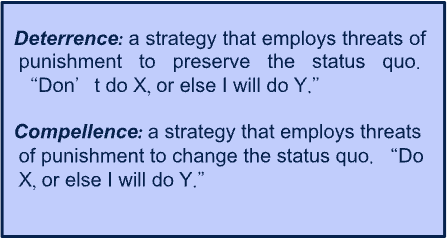

DETERRENCE AND COMPELLENCE

Assurances complement both deterrence and compellence—two distinct types of coercion. Both are attempts to affect the decision-making of a target using threats, implied or explicit. Deterrence preserves the status quo, while compellence seeks to change it.

Consider examples from the Peninsula. Preventing an invasion of South Korea or preventing the use of North Korea’s nuclear weapons are deterrent goals. Curtailing missile testing or seeking the denuclearization of North Korea are compellent goals, requiring a change from the status quo.

INDUCEMENTS

All types of assurance are distinct from inducements—pledges to reward by providing a benefit.[3] The Trump administration’s negotiating strategy with North Korea in 2019 offered such carrots. If North Korea did not denuclearize, sanctions would remain in place; but if Pyongyang did agree to denuclearize, not only would some sanctions be lifted but North Korea would also receive carrots in the form of aid and investment.

Scholarship on Credible Communication

A growing body of scholarship seeks to understand just how important credible assurance is to the success or failure of diplomacy.[4] Several findings from political science scholarship are of note.

First, there are trade-offs between making credible threats and providing reassurance. For instance, relative power tends to undermine the credibility of assurances while it enhances the credibility of threats. The stronger I am, the more likely you are to believe my threats, but the more you must also be concerned that I will hurt you anyway, even if you comply with my demands. Yet, while there are tensions between what is needed to make a threat credible and what is needed to make an assurance credible, to successfully deter or compel, both must remain sufficiently credible in the eyes of the beholder.

Second, the types of tools employed in states’ foreign policies will affect their ability to assure. For instance, the choice between economic and military coercion affects the credibility of coercive assurance. Force is generally withheld until it is carried out, whereas sanctions are often imposed until they are lifted. Avoiding a military punishment can require no action on the part of the coercer, but avoiding economic pain may require substantial action to remove imposed punishments. Moreover, sanctions are often ambiguous in their intent, whether they are coercive and meant to be lifted, or whether they have been imposed as a brute force tool.

Third, states have trouble engaging in successful diplomacy if they expect that the other side will renege in the future. Two key factors in the context of diplomacy affect the intensity of the problem. First, if reaching an accommodation diminishes a state’s relative power, it will be less able to resist future predation and therefore be more likely to stand firm today. Second, when considering concessions, governments worry about acquiring reputations for being pushovers and therefore becoming a more tempting target for future predation. Effective diplomacy must overcome these fears.

Fourth, assurances need not be explicit; they can be implied by diplomatic or military signals. Sending ‘costly signals’ is one way for leaders and governments to credibly communicate, distinguishing themselves in the minds of targets from someone who is less resolved. Paying a cost upfront is a ‘sunk cost’ signal, while acts that impose a future cost are ‘hand-tying’ signals. Cancelling or moving the location of joint military exercises is costly for South Korea and the United States, politically or monetarily. An example of a hand-tying signal is a leader making public promises. Commonly derided as cheap talk, these statements are meant to entangle the reputation of a leader with the outcome of diplomacy. If the leader of a democracy lies in public, they may be less likely to be re-elected. Yet autocrats, too, face domestic political audience costs, as dictators fear looking weak and being replaced by their rivals. Democracies and autocracies have similar overall rates of success with coercive diplomacy.[5]

Fifth, a history of distrust between governments is difficult but not impossible to overcome. Sometimes reputations for past duplicity lead to diplomatic failure. But other factors can sometimes convince leaders to overlook the past. Take, for example, the divergent effects of Western intervention in Libya and Muammar Gaddafi’s violent ouster and ultimate death. On the one hand, North Korea points to Libya’s 2003 agreement to eliminate a nuclear weapons program as a reason why Pyongyang will never forego nuclear weapons. On the other hand, Iran made a nuclear nonproliferation deal anyway in the aftermath of the 2011 Libya intervention. Concerted diplomacy overcame a reputational deficit. Later, reputations reemerged as all important. When the Trump administration reneged on the nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions, Iran was no longer willing to strike a new bargain with the United States. Despite threats of similarly severe economic consequences, Tehran defied Washington because it expected the US government to be duplicitous in the future.

Sixth, scholars generally conclude that offering carrots improves the prospect of successful diplomacy, even at the risk of being exploited or revealing a coercer’s lack of resolve.[6] Bargains built on small mutual inducements can serve as a foundation for further negotiations and can accumulate into bigger agreements. Step-by-step inducements especially guard against duplicity and can build trust when reciprocated.[7] Carrots should not, however, create adverse shifts in the balance of power, which would exacerbate commitment problems. And, like any tool of coercive diplomacy, an offer of an inducement will be evaluated by the target for its credibility—will the promised carrot materialize, or not? For instance, some blame the failure of the 1994 US–DPRK Agreed Framework, which aimed to stop North Korea’s plutonium production for nuclear weapons, on slow US progress toward constructing promised light-water reactors, which were the carrots in the bargain.[8]

The act of offering carrots can also be a signal in itself. If a target of coercion is concerned that its coercers are bent on punishment, an offer of a carrot can shake up that perception. It may convince them that punishment is not inevitable, and it may communicate an intent to strike a deal rather than go to war. In August 2013, for instance, an American offer to permit Iran to maintain a limited uranium enrichment capacity as part of a nuclear nonproliferation deal helped to accelerate back-channel negotiations that eventually led to the conclusion of a coercive bargain between the P5+1 and Iran in 2015. Carrots can be opening offers that communicate a willingness to bargain, especially if the offer comes at some domestic cost to the offeror.

Stabilizing the Korean Peninsula

TRADE-OFFS BETWEEN STABLE DETERRENCE AND DENUCLEARIZATION

Asking for too much can doom diplomacy. If coercive demands preclude a negotiated solution—i.e., the coercer is not willing to accept anything that the target is willing to concede—then negotiations fail. Powerful coercers also tend to make larger demands of their targets, endangering successful coercive diplomacy. [9] Today in the Indo-Pacific, this is why calls for the United States to define as its ultimate objective as China’s democratization are counterproductive. They undermine the credibility of US commitments to oppose unilateral changes to the status quo in the Taiwan Strait, and leave less room for bargaining with China over other important matters of trade, narcotics, and crisis management.[10]

On the Korean Peninsula, this dynamic is at play in the trade-offs between pursuing deterrent goals and compellent goals. Deterrence preserves a status quo; its aims are predictable relations, the non-use of nuclear weapons, and reduced incentives for conflict or crisis. Compellent goals aim to change the status quo; they include regime change, disarmament, or denuclearization.

These strategies interact when practiced simultaneously. Compellence weakens deterrence by suggests that the United States and South Korea will adopt a punitive approach regardless of how North Korea behaves, thereby reducing Pyongyang’s incentive to comply. Threatening to compel Pyongyang to “give up your nuclear weapons or we will hurt you” contradicts the assurance that is implied in deterrence: “we won’t hurt you unless you hurt us first.” The goal of denuclearization thus undermines the goal of deterrence on the Korean Peninsula by weakening the assurance that North Korea will find safety in not using its nuclear weapons.

This is an understandably controversial topic among allies, but policymakers ought to consider the trade-offs between the goal of denuclearization and the imperative of stable deterrence. North Korea’s nuclear arsenal is illegal and endangers the global nonproliferation regime. Nevertheless, the quest for North Korea’s denuclearization makes war on the peninsula more likely, not less. Pursuing both deterrence and denuclearization requires accepting some level of optimal instability with attendant risks of crises, conventional war, or nuclear escalation. Whatever the choice, the trade-offs between compellence and stable deterrence ought to be acknowledged explicitly.

In this context, the Lee Jae Myung administration’s stated ambition to freeze the North Korean nuclear arsenal and engage in arms control is wise. It would not undermine deterrence, as the express purpose and outcome of such discussions would be to establish risk reduction measures and communication channels—a mutually reassuring endeavour. Especially first step arms control initiatives, such as those that merely aim to increase transparency and predictability—strategic stability dialogue, a pre-launch test notification regime, and/or hotline communications—need not be thought of as compellent goals. These are mutually beneficial methods of exchange. Still, South Korean and American references to denuclearization remain and should be set aside for now, or else replaced with less direct language, perhaps by obliquely referring to the 2018 Singapore Summit statement instead.

MILITARY SIGNALLING

Military signalling on the peninsula should also prioritize deterrence over compellence. The pursuit of the denuclearization objective inclines Washington and Seoul to communicate a capability and willingness to strike first, whether to pre-empt a North Korean nuclear attack or disarm the regime. Such a policy already led the alliance toward higher risks of escalation in the 2017 crisis. The United States possesses the capability to strike deep inside North Korea. South Korea, for its part, is developing independent conventional first-strike capabilities. One destabilizing type of military signalling is demonstrating the capacity to target leadership. It reduces crisis stability by creating first strike incentives and encourages pre-delegation in command-and-control arrangements.[11] Officials in Washington and Seoul may think it is obvious that they have no intention of ordering a first strike on North Korea or overthrowing Kim Jong Un, but they should not assume that their perception is shared in Pyongyang. This is exacerbated by the fact that personalist dictatorships are prone to misperception.

A more reassuring military posture would send restrained military signals. The 2018 Comprehensive Military Agreement’s conventional arms control and risk reduction measures that reduced the proximity of North Korean and South Korean military forces were effective in this regard—no fly zones, the mutual elimination of guard posts in the DMZ, maritime protocols in the West Sea, transparency and predictability in rules of engagement. To the extent possible, these provisions should be resurrected.

Finally, Washington should keep in mind that, as a nonproliferation tool, its military signals in the region have a ceiling on their effect. More military signalling is not always better to reassure an ally. Research shows that military operations that are deemed by the public to be too provocative can end up increasing public support for an independent South Korean nuclear capability.[12]

Conclusion

This paper has reviewed the academic literature on reassurance to offer perspectives on the trade-offs between deterrence and reassurance on the Korean Peninsula. Ultimately both tools are necessary for stability. And policymakers ought to be aware that compellent goals can undermine deterrent goals via their effects on reassurance.

Of course, in any stable deterrent relationship, reassurances should be mutual. Thus, if after reassuring overtures from Seoul and Washington, North Korean reciprocation is not forthcoming, peninsular relations are more likely to spiral than stabilize.

Notes

[1]Lebow and Stein 1987; Lebow 2001; and Stein 1991. Lebow and Stein’s worked echoed Charles Osgood’s concept of Graduated Reciprocation in Tension-reduction (GRIT); Osgood 1962.

[2]Reid B. C. Pauly, The Art of Coercion: Credible Threats and the Assurance Dilemma (Cornell University Press, 2025); Reid B. C. Pauly, “Damned If They Do, Damned If They Don’t: The Assurance Dilemma in International Coercion,” International Security 49, 1 (Summer 2024). This is how Schelling (1966, 4) used the term “assurance” in Arms and Influence.

[3]This is generally accepted in the literature on coercion theory. “If assurances are akin to contracts, inducements are akin to side payments.” Art and Greenhill 2018, 23.

[4]Pauly, The Art of Coercion (2025); Pauly, “Damned If They Do, Damned If They Don’t,” (2024). See also Todd Sechser, “Reputations and Signaling in Coercive Bargaining,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62, 2 (2018): 318-345; Todd S. Sechser, “A Bargaining Theory of Coercion,” in Greenhill and Krause (eds.), Coercion (2018), 55-76; Matthew Cebul, Allan Dafoe, and Nuno Monteiro, “Coercion and the Credibility of Assurances,” Journal of Politics 83,3 (2021); James W. Davis, Threats and Promises (JHU Press, 2000; Jeffrey W. Knopf (ed.), Security Assurances and Nuclear Nonproliferation (Stanford University Press, 2012); Tristan Volpe, “Atomic Leverage: Compellence with Nuclear Latency,” Security Studies 26, 3 (2017): 517-544; Max Abrahms, “The Credibility Paradox: Violence as a Double-Edged Sword in International Politics,” International Studies Quarterly 57,4 (2013): 660-671; Wyn Bowen, Jeffrey Knopf, and Matthew Moran, “The Obama Administration and Syrian Chemical Weapons: Deterrence, Compellence, and the Limits of the ‘Resolve plus Bombs’ Formula,” Security Studies 29, 5 (2020): 797-831; Thomas Christensen, Worse Than a Monolith: Alliance Politics and the Problem of Coercive Diplomacy in Asia (Princeton University Press, 2011); Bonnie Glaser, Jessica Chen Weiss, and Thomas Christensen, “Taiwan and the True Sources of Deterrence: Why America Must Reassure, Not Just Threaten, China,” Foreign Affairs 103,1 (January/February 2024).

[5]Alexander B. Downes and Todd S. Sechser, “The Illusion of Democratic Credibility,” International Organization 66, 3 (Summer 2012): 457-489.

[6]Richard Haass and Meghan O’Sullivan, Honey and Vinegar: Incentives, Sanctions, and Foreign Policy (Brookings, 2000); Han Dorussen, “Mixing Carrots with Sticks: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Positive Inducements,” Journal of Peace Research 38,2 (2001); Miroslav Nincic, The Logic of Positive Engagement (Cornell University Press, 2011).

[7]Robert Keohane, After Hegemony (Princeton University Press, 2005); Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (Basic Books, 1984); Robert Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30, 2 (1978), 181.

[8]David C. Kang, “Response: Why Are We Afraid of Engagement?” in David C. Kang and Victor D. Cha, Nuclear North Korea: A Debate on Engagement Strategies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 101–127. North Korea cheated anyway. See also Christopher Lawrence, “Normalization by Other Means: Technological Infrastructure and Political Commitment in the North Korean Nuclear Crisis,” International Security 45, 1 (2020): 9–50, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00385.

[9]Todd S. Sechser, “A Bargaining Theory of Coercion,” in Greenhill and Krause (eds.), Coercion (2018).

[10]Jessica Chen Weiss and James B. Steinberg, “The Perils of Estrangement,” Foreign Affairs (July/August 2024).

[11]A 2022 DPRK law mentions “automatic” procedures for the use of nuclear weapons, a possible reference to pre-delegation. “North Korea’s Kim Jong Un Vows to Never Give Up Nuclear Weapons,” Radio Free Asia, September 9, 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/nuclear_law-09092022184333.html.

[12]Lauren Sukin, “Credible Nuclear Security Commitments Can Backfire: Explaining Domestic Support for Nuclear Weapons Acquisition in South Korea,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 64, 6 (2020), 1011–1042.

The Author

REID B. C. PAULY

Reid Pauly is Assistant Professor of Political Science and the Dean’s Assistant Professor of Nuclear Security and Policy at Brown University's Watson School of International and Public Affairs. He studies nuclear proliferation and nuclear strategy, coercion, and secrecy in international politics. Pauly is the author of The Art of Coercion: Credible Threats and the Assurance Dilemma (Cornell University Press, 2025). His scholarship has also been published in International Security, International Studies Quarterly, the European Journal of International Relations, and Foreign Affairs. Pauly earned his Ph.D. from MIT and has held fellowships at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, the Schmidt Futures International Strategy Forum, and Dartmouth College’s Dickey Center for International Understanding.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org