Global Challenges to Democracy Report No.234

From Backsliding to Recalibration? Trump 2.0 and Democracy in the Philippines

Aries A. Arugay

July 21, 2025

This report analyses the three-fold impact of the Trump 2.0 presidency on Philippine domestic politics, economic sectors, and foreign policy. It argues that Trump’s restoration could reinforce authoritarian tendencies in the Philippines, undermine its economic resilience amid shifting global trade regimes and increasing economic coercion from China, and constrain its capacity for strategic autonomy within a highly volatile, uncertain, and complex international order.

Contents

- Introduction

- Duterte’s Rise to Power

- Philippine democracy and its illiberal discontents

- Trump 2.0 and Philippine democracy

- Conclusion: Toward strategic and democratic resilience in uncertain times

Introduction

The return of Donald Trump to the United States presidency, whether as historical déjà vu or democratic erosion’s most potent manifestation in the world so far, indicates a critical watershed in US foreign policy. Its far-reaching repercussions are particularly salient for the Philippines—a treaty ally deeply embedded in the US security architecture, an emerging economy tightly integrated with American markets, and a democratic polity steeped in postcolonial entanglements with its former colonizer. The Trump 2.0 administration—projected to be more ideologically rigid, isolationist, and confrontational—has significant implications for the Philippines’ political development, economic stability, and diplomatic positionalities.

Yet again, Trump’s restoration to the zenith of American power could not come at a more complicated domestic political dispensation in the Philippines. During his first term of office (2017–2021), Southeast Asia’s oldest democracy voted populist firebrand Rodrigo Duterte as its president in 2016. These two strongmen had a lot in common, so much so that they had cordial interactions when Trump attended the summits organized by the Philippines as Chair of the Association of Southeast Asia held in Manila in November 2017 (Kurlantzick 2017). The potential ‘bromance’ between the two strongmen, however, did not materialize in deeper ties between the two countries. Philippines–US relations deteriorated given Duterte’s pivot to China and his disdain for the US alliance resulting in the almost abrogation of the Visiting Forces Agreement between the two allies (Arugay and Storey 2023).

On the domestic front, the US under Trump 1.0 was radio silent while Duterte deliberately assaulted the democratic institutions of the Philippines and waged a bloody war that killed tens of thousands of mainly Filipino drug dependents in the country’s poorest neighbourhoods. Expressions of alarm started only at the tail end of the Duterte presidency under the Biden administration in 2021 (Arugay 2024). By then, Duterte succeeded in eroding Philippine democracy to the extent that it became easy for authoritarian nostalgia to catapult Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., son and namesake of the country’s brutal dictator, as president and Rodrigo’s own daughter, Sara Duterte, as vice-president after the 2022 elections (Arugay et al. 2024).

This paper analyses the three-fold impact of the Trump 2.0 presidency on Philippine domestic politics, economic sectors, and foreign policy. It argues that Trump’s restoration could reinforce authoritarian tendencies in the Philippines, undermine its economic resilience amid shifting global trade regimes and increasing economic coercion from China, and constrain its capacity for strategic autonomy within a highly volatile, uncertain, and complex international order. As a background, this paper discusses the extent of democratic backsliding in the Philippines under Rodrigo Duterte prior to the Marcos Jr. administration (2022– present).

Duterte’s Rise to Power

Between 2016–2022, Duterte’s anti-democratic predispositions such as pandering to and politicizing the military and police, intimidating the political opposition, launching a spate of extra-judicial killings, and attacking media freedoms have done serious damage to Philippine democracy (Arugay and Baquisal 2023). Many of these harms are not merely transient but will likely become fixtures of Philippine politics in the years to come. However, it is also important to discuss the nuances of Duterte’s relationship with democracy, commonly defined as a political system where political leadership is selected through free, fair, and competitive elections and where citizens enjoy substantial political and civil liberties to meaningfully partake in political decision-making (Schmitter and Karl 1991; Moller and Skaaning 2013). One critical factoid of Philippine politics is that Duterte enjoyed near-70 percent approval ratings throughout his term—an unprecedented affirmation of public dissatisfaction with a nominal democracy that has historically left much to be desired and a tacit endorsement of Duterte’s politics (Parmanand 2023; Ducanes et al. 2023).In 2019, the opposition did not win a single seat in the Senate election while Filipinos voted in 2022—for the first time in three decades— for a continuity ticket promising to continue Duterte’s brand of governance. Duterte’s campaign slogan of ‘change is coming’ indeed reverberated beyond his presidency as carried out by the Marcos–Duterte alliance.

Duterte was elected in 2016 with the popular slogan ‘change is coming’. Unlike his predecessor, Benigno Aquino III, who catapulted himself into the national spotlight on a campaign for political liberalism, the mayor from Davao leapfrogged to the presidency through a wave of public anger: against alleged criminals, oligarchs, condescending Western countries preaching human rights over effective governance, and many other roadblocks to Philippine development (Pepinsky 2017; Viray 2016). The substance of the Filipino populist’s platform defied scholarly categories however. Duterte was a conservative on law-and-order issues while also criticizing economic oligarchs, US imperialism, and governmental apathy for the poor—all of which are traditionally seen as left-of-centre politics (Parcon 2021).

Duterte expended his political capital instead on law-and-order issues such as doubling the salaries of state security forces, publicly attacking democratic norms of liberalism and human rights, and executing his war on drugs. More than a third of between 12,000–30,000 estimated killings occurred in his first three months in office (Iglesias 2023). Between 2016–2018, there were persistent calls by the president’s supporters for Duterte to establish a ‘revolutionary government’. Duterte himself briefly entertained the rhetoric in 2019, threatening to arrest detractors: “I have enough problems with criminality, drugs, rebellion and all, but if you push me to the extreme, I will declare the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus and I will arrest all of you” (Gomez 2019).

Moreover, Duterte himself attributed his strong criticism of the US and heavy praise of China to the issue of human rights conditionalities in foreign aid from Western donors, which Duterte saw as political interference. The Filipino sociologist Randy David (2017) called this phenomenon ‘Dutertismo’, a “style of governance enabled by the public’s faith in the capacity of a tough-talking, willful, and unorthodox leader to carry out drastic actions to solve the nation’s persistent problems” and “will not allow anyone or anything to stand in his way”. However, from its inception the nature of Dutertismo and its relationship with democracy has been widely debated.

Beginning in 2017, Duterte’s policies began to instrumentalize public support as a disciplinary tool against society. Moreover, the populist leader started to dominate Philippine politics by refusing to honour power- sharing agreements with coalition partners. In 2017, Duterte’s allies in Congress did not confirm cabinet secretaries (ministers) from the social welfare, agrarian reform, and anti-poverty portfolios because of opposition from business groups and the political establishment. The leftist Makabayan bloc then exited the congressional majority. In the same year, Duterte formed the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) which became notorious for ‘red tagging’ or labelling individuals or groups as ‘fronts’ of the local communist insurgents, often without proof or follow-up litigation (Marasigan 2022). NTF- ELCAC is a mechanism that was popular in the defence establishment and among many social media influencers who supported Duterte.

What emerged from the coalitional in-fighting within Duterte’s camp closer to the middle of his term is a more coherent support base composed of economically moderate technocrats and highly illiberal political partisans. With the marginalization of progressive elements in Duterte’s ruling coalition, Dutertismo therefore came to be defined less by populism and more by its illiberalism given his disdain with liberal-minded opposition politicians. In this sense, Duterte has been dubbed as a ‘demobilizing populist’ who requires silent obedient consent from the public. Popular support was instrumentalized to strengthen Duterte’s hand vis-a- vis other politicians but was not mobilized in support of conventional left-wing populist policies attacking the ‘elite’ like wealth transfers, nationalization of industries, and radical attempts to foster economic equality.

Duterte’s presidency was characterized by a lack of transparency in the use of public funds (e.g. ballooning ‘confidential fund’ budget), the harassment of civil society organizations, and a heightened sense of importance for the police and the military in domestic governance (Arugay 2023). As Kenny (2020) argues, some populist movements are more personalistic than others if they are unmediated by political parties and clientelistic networks, which is Duterte’s case. Most crucially, the ‘public’ under Duterte’s governance style was subordinated to the president rather than a defined programmatic agenda carried out by institutions or social movements. The firebrand populist governed in ways different from his campaign promises, including an unexpected warming of relations with Beijing (he never expressed pro-China sentiments during his electoral campaign) and comfort in working with many oligarchs whom he criticized. Duterte also had a penchant for flip-flopping on core policy issues, as is shown with his dramatic break from the Philippine Left.

Philippine democracy and its illiberal discontents

The erosion of Philippine democracy under Duterte was evident by all measures of democratic quality. Notably, there were significant declines in the country’s human rights observance, freedom of the press and expression, rule of law, and the efficacy of its guardrails against executive concentration of power. All these aspects of democracy were steadily and gradually eroded over time. Duterte, however, was not the first Philippine post-democratization president to attack the press or to try to break free from institutional checks and balances. What made him a critical juncture in Philippine post-1986 history was that he was the first to systematically attack liberalism as an executive policy.

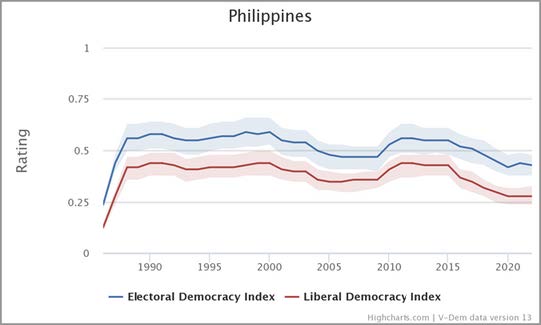

If democracy is viewed as a sum of various parts, it was observed that electoral quality has remained the same under Duterte, while liberal components of democracy such as civil society strength and rights-based indicators of democratic quality have severely worsened as seen below:

Figure 1: Comparison of the dimensions of Philippine democracy (1986-2022)

Source: Varieties of Democracy project

In many ways, Duterte’s popular appeal sharpened conceptual tensions between two pillars of democracy: vertical accountability––those relating to direct popular mandate––and horizontal accountability or the restraints on concentrations of power, particularly in the executive. But with such significant attacks on liberal components of democracy in the Philippines, more scholars have now labelled the Philippines as ‘backsliding’ rather than merely ‘careening’ or muddling through an electoral democracy wrought with many defects (Arugay and Slater 2019).

Duterte’s autocratization project is a programmatic agenda, one that reverberates beyond his presidency and is carried out by allied political entrepreneurs as seen under the current Marcos Jr. administration. It goes beyond personal misogynistic statements and inflammatory gutter language. For example, the legacy of the drug war has reinforced longstanding cultures of impunity and vertical violence between the Philippine state and its citizens but also took them to new heights unprecedented in recent decades (Reyes 2016).

This propensity for political violence goes side by side with another Duterte legacy: the re-militarization of politics in the Philippines. This manifested in various ways, including the appointment of retired security sector personnel in civilian leadership posts and the disposition for coercion-heavy rule even when it was inappropriate such as during the COVID-19 pandemic (Baquisal and Arugay 2023). In making the security sector so critical to the country’s governance, Duterte’s legacy stands to undo decades of efforts since 1986 to put the military under democratic civilian control (Lee 2020).

Dutertismo would not have made a strong and possibly lasting impact on democratic erosion if not for the rise of disinformation, a tool that was instrumental in his 2016 electoral victory (Ong and Tapsell 2022). Fake narratives amplified by social media through state sponsored troll and influencer armies dominated the country’s information and civic space. It not only promoted Duterte’s illiberal assaults against pro-democracy political actors but also allowed the revisionist narratives of the Marcos dynasty and their brand of autocratic politics. Many of Duterte’s supporters boldly used social media in agitating the opposition, including disclosures of unsubstantiated coup-plotting matrices and McCarthyist witch hunts against Duterte’s critics (Gaw et al. 2023).

Duterte ended his term in 2022 and handed power to a powerful coalition led by the son of another Philippine populist-authoritarian leader in the past, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and his own daughter Sara Duterte as vice- president. This dynastic alliance was hugely popular and won the 2022 elections with an unprecedented majority electoral mandate. Not known to have liberal and progressive ideological viewpoints, both Marcos Jr. and Sara Duterte cast further doubt on positive prospects for democratic recalibration in the Philippines.

Trump 2.0 and Philippine democracy

Trump’s populist, anti-establishment rhetoric has continued to inspire or embolden similar trends among global strongmen. His first presidency contributed to the diffusion of illiberal norms—attacks on the press, delegitimization of electoral processes, disdain for multilateralism—that resonated strongly as well as occurred simultaneously with similar efforts in the Philippines. Under President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the Philippines’ democratic erosion continued with the further weakening of its accountability institutions, harassment of media, and sustained executive aggrandizement.

The momentum for autocratization diminished with the Biden presidency that saw mutual lines of cooperation with the Philippines under Marcos Jr. such as strengthening the security alliance as well as recognizing the importance of respecting human rights and the rule of law (PCO 2023). However, a second Trump presidency may disincentivize domestic elites by reducing normative pressure from Washington. During Trump’s first term, his administration remained largely silent on Duterte’s bloody war on drugs despite mounting evidence of extrajudicial killings. The absence of condemnation from a major ally like the U.S. was not lost on Filipino officials, many of whom interpreted the silence as tacit approval or indifference.

This permissiveness increases risks under Trump 2.0. While the Biden administration adopted a more values- based foreign policy—highlighted by Vice President Kamala Harris’s visit to Palawan (southern Philippines) in 2022 and vocal support for media freedom—the likely recalibration under Trump would prioritize security and transactional interests over democratic norms which has been pursued by the US since the end of the Cold War. In such a context, democratic erosion in the Philippines could accelerate, especially as the Marcos Jr. administration faces a mounting challenge from the Duterte dynasty given the unravelling of their political alliance by 2024.

Moreover, the elements of Duterte’s populist playbook that often involve scapegoating marginalized sectors, weaponizing disinformation, and discrediting good governance have remained despite his formal exit from the presidency. The social media infrastructure that enabled Trump’s rise and Duterte’s populist insurgency remains intact, posing sustained threats to evidence-based policymaking and electoral integrity (Arugay and Mendoza 2024.)

Beyond the political consequences, the Philippine economy is significantly exposed to the radical shifts in US economic policies launched by the Trump administration.

Beyond the political consequences, the Philippine economy is significantly exposed to the radical shifts in US economic policies launched by the Trump administration. Although the country’s trade has diversified—China is now its largest trading partner—the US remains a major export destination, particularly for electronic components and apparel. In 2023, Philippine exports to the US totalled approximately $11.2 billion, representing about 14.7% of total exports (Philippine Statistics Authority 2024). Any movement toward protectionism, such as renewed tariffs or the abrogation of trade preferences, would directly affect key manufacturing sectors and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) dependent on US demand.

Trump’s prior disdain for multilateral trade agreements, including his decision to withdraw from the Trans- Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, signals potential disruption to the global trading order. Should Trump 2.0 seriously implement such protectionist policies, Philippine exports could suffer from heightened tariff exposure or nontariff barriers. Furthermore, the Philippines’ long-standing attempt to join successor trade frameworks like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) may receive less traction in a US-dominated trade environment hostile to multilateral trade.

The implications extend to the business process outsourcing (BPO) sector, a vital source of foreign exchange and urban employment. US clients account for over 60% of the Philippine BPO market. In 2023, the sector employed more than 1.5 million Filipinos and generated $35.9 billion in revenues (IBPAP 2024). If Trump renews incentives for reshoring services or imposes digital protectionism—such as through federal procurement restrictions or data localization mandates—this could erode the Philippines’ cost advantage and deter investment in ICT services.

The remittance economy is similarly vulnerable. The US is the top source of overseas Filipino remittances, accounting for $12.1 billion or roughly 41% of total remittances in 2023 (BSP 2024). These funds sustain millions of households and contribute 9% to national GDP. A Trump 2.0 administration could reinvigorate hardline immigration policies, including visa caps, employment restrictions, and anti-diversity rhetoric, that disproportionately affect healthcare workers, caregivers, and professionals of Filipino descent. Even if formal policy changes are limited, heightened xenophobia and legal uncertainty could deter migration or endanger Filipino diaspora communities.

For emerging economies like the Philippines, which rely on consistent capital inflows to sustain infrastructure spending and peso stability, such volatility could increase financing costs. The Marcos administration’s ambitious infrastructure agenda under ‘Build Better More’ may thus face higher sovereign risk premiums or delayed project implementation amid global capital flight to safer assets. Thus, Trump 2.0’s economic policies will have a significant impact on the ability of the Philippine government to maintain and/or sustain political legitimacy through effective performance including delivering economic growth and development. If the US under Trump will disengage economically or not help the Philippines reach its development targets under the Marcos Jr., presidency, it will generate the energy to question the viability of the country’s democratic regime and help lure the electorate to elect more populist authoritarian elites in subsequent electoral cycles, particularly the scheduled presidential elections in 2028. Finally, US economic disengagement will stem efforts of the Philippines to be less economically dependent on China and therefore more vulnerable to its economic coercive tactics that will not bode well on its current stance to resist Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific region.

Perhaps the most complicated impact of Trump 2.0 lies in Philippine foreign policy. The strategically located Southeast Asian country has long navigated a delicate balancing act between its mutual defence treaty alliance with the US and its growing economic ties with China. Trump 2.0 could upend this calculus by introducing both uncertainty in the alliance and increased pressure to side with Washington in its strategic rivalry with Beijing.

While the Philippines–US Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) remains the cornerstone of bilateral security ties and an indispensable pillar of US Indo-Pacific strategy, Trump’s earlier comments calling alliances ‘unfair’ and ‘obsolete’ raised alarm across East Asia. He demanded greater burden-sharing from allies like Japan and South Korea and reportedly considered troop withdrawals from Germany and the Korean Peninsula. The Philippines could face similar expectations—particularly in terms of defence cost-sharing or expanded access under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). While this may deepen operational coordination, it could also stoke domestic backlash if perceived as undermining national sovereignty.

In the South China Sea, the Marcos Jr. administration has adopted a more assertive stance than its predecessor, increasingly relying on US support amid rising Chinese incursions. The 2016 arbitral ruling that invalidated China’s expansive claims remains unenforced, while incidents involving water cannon use and military-grade lasers against Philippine vessels have increased (AMTI 2024). Under Biden, Washington expressed public support for the arbitral ruling and reaffirmed that attacks on Philippine armed forces would invoke Article IV of the MDT.

Trump’s contempt for multilateralism, evident in his withdrawal from the WHO and climate accords, could fragment regional security efforts and reduce collective deterrence.

However, Trump’s return could diminish such diplomatic clarity. If his transactional foreign policy resumes, the Philippines may find itself with diminished U.S. diplomatic cover in confronting Beijing. Worse, a sudden rapprochement between Trump and Xi Jinping—similar to past personalist overtures—could lead to de facto acquiescence to China’s assertiveness, leaving Manila exposed. This is salient given the Marcos Jr. administration’s approach of exposing China’s undue aggression in the South China Sea.

At the same time, the Philippines is cultivating strategic partnerships beyond the US–China dyad, including deepened defence ties with Japan, Australia, and South Korea. However, the cohesion of these relationships depends in part on US leadership within the Indo-Pacific framework. Trump’s contempt for multilateralism, evident in his withdrawal from the WHO and climate accords, could fragment regional security efforts and reduce collective deterrence.

This raises the dilemma of strategic entanglement versus autonomy. While US defence support remains indispensable, overreliance on a volatile partner risks undermining the Philippines’ long-term strategic interests. To maintain agency, Manila must invest in credible defence capabilities, broaden its diplomatic engagements, and institutionalize its foreign policy beyond presidential personalities.

Conclusion: Toward strategic and democratic resilience in uncertain times

The return of Donald Trump to the US presidency portends a turbulent external environment for the Philippines. Politically, it may embolden illiberal actors and erode democratic norms by eliminating normative guardrails. Economically, it exposes key sectors to trade disruptions, investor flight, and labour market constraints. In foreign policy, it complicates alliance management, heightens regional insecurity, and constraints strategic manoeuvrability.

This paper has not only pointed out the novel ways in which the Duterte presidency adversely impacted Philippine democracy, but also how Duterte’s anti-democratic advances were stifled or moderated by structural factors and conscientious efforts by political actors. First, while Philippine society continues to be torn apart by pernicious political polarization, there are indications that pockets of Philippine democracy have matured and have proved resilient. The democratic opposition––despite suffering significant state-backed intimidation under Duterte––has chosen to cast their lot in elections and to respect the results, regardless of their defeat. It is an understated fact that the Philippines has not seen significant ‘civil society coups’ like people power movements despite what both pro- and anti-administration camps claim is an existential struggle for control over the future of the country. To be sure, such moderation is likely because of the significant public support shored up by the Duterte administration over the opposition, which has prevented political destabilization. Compounding the Philippines’ democratic deficits is the growing trend for political dynasties in the families to entrench themselves across all levels of government (Teehankee 2018).

Two important pillars of democracy will take time to rebuild after Duterte: maintaining or even improving electoral integrity and regaining public trust in liberal principles such as human rights, freedom of speech, and rule of law. For reasons identified in this chapter, Philippine democracy is regrettably likely to be on the defensive in the coming years, struggling to survive and would careen at best. In the current political environment, illiberal politicians have higher odds of winning elections, partly because of voters’ attitudes as well. Democratic consolidation cannot realistically take hold if first-order principles that make up democracy are under attack, both from political elites and significant portions of the population. At the same time, there remain credible threats of regime diminution from electoral democracy to non-democracy, particularly given alarming trends––principally from the Duterte camp in 2024––calling on the military’s intervention amid the feud between the Marcos and Duterte families (Gavilan 2024). Duterte is no longer the president, but the autocratization that Dutertismo paved is very much alive.

While Trump 2.0 may not pay attention to directly addressing the democratic erosion challenges of the Philippines, pro-democratic actors in the US and the rest of the world need to find ways to help states like the Philippines to recalibrate their democracies or help foster their resilience. More innovative ways that emphasize the mutuality of interests between the US and the Philippines must give way to conventional policies and the usual measures. Yet these challenges also offer an impetus for recalibration. The Philippines must not fall into the trap of binary alignments or reactive diplomacy. Instead, it should pursue a proactive strategy of democratic resilience, economic diversification, and foreign policy autonomy. The sustainability of democratic and strategic choices must be rooted in internal consensus, not external tutelage.

Only by anchoring its policies in national interest—tempered by normative commitments and institutional strength—can the Philippines weather the coming storms of great power politics and emerge with its sovereignty intact and its democracy preserved.

WORKS CITED

Arugay, A.A. 2024. “Philippine Democracy Despite Duterte.” Global Asia, 19(1): 56–61.

Arugay, Aries A. 2023. “Militarizing Governance: Informal Civil–Military Relations and Democratic Erosion in the Philippines.” In Alan Chong and Nicole Jenne (eds.) Asian Military Evolutions: Civil–Military Relations in Asia. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp. 68–89. https://doi.org/10.51952/9781529229349.ch004

Arugay, A. A., and J.K.A. Baquisal. 2023. “Bowed, Bent, & Broken: Duterte’s Assaults on Civil Society in the Philippines.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 42(3), 328–349.

Arugay, A.A., J. Encinas-Franco, and J.K.A. Baquisal. 2024. “Introduction: Change and Continuity Narratives in the Philippines from Duterte to Marcos Jr.” In Arugay, A.A. and Encinas-Franco, J. (eds.). Games, Changes, and Fears: The Philippines from Duterte to Marcos Jr. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, pp. 1–30.

Arugay, A.A. and M.E.H. Mendoza. 2024. “Digital Autocratisation and Electoral Disinformation in the Philippines.” Perspective, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2024/53. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2024-53-digital-autocratisation-and-electoral-disinformation-in-the-philippines-by-aries-a-arugay-maria-elize-h-mendoza/.

Arugay, A.A. and D. Slater. 2019. “Polarization Without Poles: Machiavellian Conflicts and the Philippines’ Lost Decade of Democracy, 2000–2010.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1): 122–136.

Arugay, A.A. and Storey, I. 2023. “A Strategic Reset?: The Philippines-United States Alliance under President Marcos Jr.”, Perspective, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2023/40. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ISEAS_Perspective_2023_40.pdf

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). 2024. Overseas Filipinos’ Remittances Annual Report.

https://www.bsp.gov.ph/SitePages/MediaAndResearch/MediaDisp.aspx?ItemId=7426

Baquisal, J.K.A. and A.A. Arugay. 2023. “The Philippines in 2022: The "Dance" of the Dynasties.” Southeast Asian Affairs, 2023, 234–253. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/895957.

David, R. 2017. “Where is ‘Dutertismo’ headed?”Philippine Star, December 17.

Ducanes, G/ M., S. Rood, and J. Tigno. 2023. “Sociodemographic Factors, Policy Satisfaction, Perceived Character: What Factors Explain President Duterte’s Popularity?” Philippine Political Science Journal, 44(1):1–42.

Gavilan, J. 2024. “Duterte warns Marcos of ouster like his father’s if charter change pushes through.” Rappler, January 28.

Gaw, F. et al. 2023. Political Economy of Covert Influence Operations in the 2022 Philippine Elections. Internews, https://internews.org/resource/political-economy-of-covert-influence-operations-in-the-2022-philippine-elections/.

Gomez, J. 2019. “Duterte warns of ‘revolutionary government’ and arrests.” Associated Press, April 5.

IBPAP. 2024. Annual IT-BPM Industry Report. IT and Business Process Association of the Philippines.

Iglesias, S. 2023. “Explaining the pattern of “war on drugs” violence in the Philippines under Duterte”. Asian Politics & Policy, 15(2): 164–184.

Kenny, P. D. 2020. “Why is there no political polarization in the Philippines?” Old divisions, new dangers: Political polarization in South and Southeast Asia. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Kurlantzick, J. 2017. “Trump's Visit to the Philippines: A Budding Bromance but Few Positive Outcomes.” Asia Unbound, Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/blog/trumps-visit-philippines-budding-bromance-few-positive-outcomes.

Lee, T. 2020. “The Philippines: Civil-Military Relations, from Marcos to Duterte.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1845

Marasigan, T. 2022. “Red-tagging as a human rights violation in the Philippines”. New Mandala, 13 April.

Moller, J. and S. Skaaning. 2013. Democracy and Democratization in Comparative Perspective: Conceptions, Conjunctures, Causes and Consequences. New York: Routledge.

Ong, J. C., and Tapsell, R. 2022. “Demystifying disinformation Shadow Economies: Fake News Work Models in Indonesia and the Philippines.” Asian Journal of Communication, 32(3), 251–267.

Parcon, I.C. 2021. “Understanding Dutertismo: Populism and Democratic Politics in the Philippines.” Asian Journal of Social Science, 49(3): 131–137.

Parmanand, S. 2023. Democratic backsliding and threats to human rights in Duterte’s Philippines. In A. Brysk (ed.), Populism and Human Rights in a Turbulent Era, 105-125, United States: Edward Elgar Publishing.

PCO (Presidential Communications Office). 2023. “Marcos, Biden expand security, environment protection, trade ties; affirm commitment to international law.” https://pco.gov.ph/news_releases/marcos-biden-expand-security-environment-protection-trade-ties-affirm-commitment-to-international-law/.

Pepinsky, T.B. 2017. “Southeast Asia: Voting against Disorder.” Journal of Democracy, 28(2): 120–131.

Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). 2024. Foreign Trade Statistics of the Philippines. https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/export-import/annual/index.

Reyes, D.A. 2016. “The spectacle of violence in Duterte's ‘war on drugs’.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 35(3), 111–137.

Schmitter, P.C. and T.L. Karl. 1991. “What Democracy is… and is not.” Journal of Democracy, 2(3): 75–88.

Teehankee, J. 2023. “Beyond nostalgia: the Marcos political comeback in the Philippines.” Southeast Asia Working Paper Series, Paper No. 7. London School of Economics.

Viray, P. L. 2016. “Duterte admits to bloody presidency if he wins.” Philippine Star, February 21.

The Author

ARIES A. ARUGAY

Aries A. Arugay is Professor, Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines Diliman. Aries is Editor-in-Chief of Asian Politics & Policy, a Scopus-indexed academic journal published by Wiley-Blackwell and the Policy Studies Organization. He is also a Visiting Senior Fellow and Coordinator of the Philippines Studies Programme of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies-Yusof-Ishak Institute (Singapore). Aries obtained his PhD in Political Science from Georgia State University (United States) in 2014 as a Fulbright Fellow and his MA and BA (cum laude) in Political Science from the University of the Philippines-Diliman.

Email: aaarugay @up.edu.ph.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org