Climate Change and Conflict Report No.196

Climate Change's Intangible Loss and Damage: Exploring the Journeys of Pacific Youth Migrants

Ria Shibata, Sylvia Frain, Iemaima Vaai

January 01, 1970

The report analyses the findings from a series of Talanoa discussions with young Pasifika migrants living in diaspora communities across Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and USA. It narrates the personal journeys of these young individuals as they cope with the pain of separation from their ancestral lands, and navigate their journey to preserve their identity, dignity, social cohesion and selfhood. The experiences of these youth migrants highlight some of the challenges related to intangible losses and damages that host countries and diaspora communities could address if they are to aid future climate-related migration effectively and assist the integration of migrants into their new societies.

Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Introduction & Background

- Method

- Findings

- Discussion & Recommendations

- Conclusions

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Toda Peace Institute’s programme on Climate Change and Conflict. The research team would like to thank the Ministry for Pacific Peoples of New Zealand for their guidance, as well as the invaluable support from the Pacific youth climate change activists, members of the Tuvalu community in Auckland, Tuvalu Auckland Community Trust, the Warkworth Kiribati community, and the Mahu Vision Community Trust of Auckland. The team is deeply grateful to Kevin Clements, Volker Boege, John Campbell, Upolu Luma Vaai, Carol Farbotko, and Taukiei Kitara for their insightful and constructive comments and their generous time in reviewing our manuscript. Most of all, we would like to sincerely thank the young Pasifika participants for the willingness to offer their time to share their precious journeys to make this study possible.

Executive Summary

CLIMATE CHANGE’S INTANGIBLE LOSS AND DAMAGE: EXPLORING THE JOURNEYS OF PACIFIC YOUTH MIGRANTS

Climate change represents a critical challenge for the Pacific region, where numerous small island states confront distinctive and intricate difficulties as a result of rapid transformation of environmental conditions. The rise of sea levels, ocean acidification and coastal erosion, rising temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and an increased frequency of extreme weather events like tropical cyclones, floods and droughts all carry significant repercussions for social, economic, political and human security. Among small island states in the Pacific, atoll countries such as the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and Kiribati are viewed as particularly vulnerable to changes in climatic conditions (IPCC, 2023; Mimura et al., 2007; Barnett &Campbell, 2010; Nurse et al., 2014; Mycco et al., 2022).

As the Pacific communities continue to advocate for mitigation and adaptation, the rise in sea levels, consequent coastal flooding and saltwater encroachment, may render some islands uninhabitable if in-situ adaptation measures are insufficient or remain unfunded. While movement away from climate-impacted areas can often be achieved locally or within national borders, international migration can be a viable choice for some people whose livelihoods are drastically undermined by climate change.

These irreversible and reversible losses caused by climatic changes not only endanger Pacific peoples’ economic livelihoods but also their physical and mental well-being. Climate change-induced migration and displacement could lead to loss of unique ecosystems, fragmentation of communities, and erosion of social structures and relationships. Should residents be compelled to migrate, the damaging repercussions on their spirituality, identity, and security rooted in place could be profound. Loss and damage impacts are complex. Such non-economic loss and damage (NELD) or adverse impacts of climate change cannot be easily quantified in financial terms, and can have significant and lasting effects on the communities.

This study explores the experiences of Pasifika youth who have migrated internationally to countries such as Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the United States (Hawai’i). Although these atoll migrants have not necessarily experienced displacement or forced relocation due to climate change impacts, some have undergone involuntary migration to different countries. They have been unwillingly uprooted from their familiarPacific cultural surroundings and forced to adapt to new environments. The study aims to learn from the experiences of these youth migrants in Western diasporas. It analyses the nuanced dimensions of intangible loss and damage faced by young Pasifika migrants as they navigate the critical emotional, cultural, and societal ramifications associated with the loss of connection to their ancestral lands.

The study brought to light various non-material challenges that Pacific migrants experience when they migrate internationally. The findings raise important questions about the risks and needs associated with climate-induced migration.The stories of the Pasifika youth have highlighted that intangible assets such as cultural heritage and indigenous knowledge, social cohesion, place-based identity, and sense of belonging are as important to their well-being as quantifiable economic resources. The difficult journeys of Pacific youth illustrate a glaring oversight in current global, regional and national climate mobility policies, and discourses on climate-induced loss and damage, which primarily focus on economic losses.

The recognition of non-economic losses that involve irreversible damages to the migrants’ sense of selfhood and way of life is vital for understanding the full scope of climate change impacts, particularly in vulnerable regions such as small island states. Evaluation of non-economic losses may be challenging as they are not easily quantifiable. However, this study calls upon governments and policy makers involved in global climate negotiations to acknowledge the critical need to address intangible losses and damages in a holistic and integrated manner.

Introduction & Background

Climate change induces extreme weather events, alters the global ecosystems, and can lead to resource scarcity, socio-economic upheaval, and human migration. Pacific Island countries, especially low-lying atoll nations such as the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and Kiribati, are particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and intensified weather events. Residents of some small islands and low-lying coastal areas may face relocation or forced displacement, confronting a myriad of challenges in unfamiliar territories that may threaten their dignity and cultural identity. This chapter analyses the findings from a series of Talanoa discussions with young Pasifika migrants from Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Marshall Islands aged between 19 and 33 years old, living in diaspora communities across Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the United States (n=30). It narrates the personal journeys of these young individuals as they cope with the pain of separation from their homelands, and as they navigate their journey to preserve their dignity and selfhood. The experiences of these youth migrants highlight some of the challenges related to intangible loss and damage that host countries and diaspora communities could address if they are to aid future climate-related migration effectively and assist the integration of migrants into their new societies.

Climate change represents a critical challenge for the Pacific region, where numerous small island states confront distinctive and intricate difficulties as a result of rapid transformation of environmental conditions. The rise of sea levels, ocean acidification and coastal erosion, rising temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and an increased frequency of extreme weather events like tropical cyclones, floods and droughts, all carry significant repercussions for social, economic, political and human security. Among small island states in the Pacific, atoll countries such as the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and Kiribati are viewed as particularly vulnerable (IPCC, 2023; Mimura et al., 2007; Barnett & Campbell, 2010; Nurse et al., 2014; Mycco et al., 2022) to changes in climatic conditions.

As the Pacific communities continue to advocate for mitigation and adaptation so that they can stay in their islands, in some cases relocation, particularly away from coastal areas, is also being integrated into future planning. The rise in sea levels, consequent coastal flooding and saltwater encroachment, may render some islands uninhabitable if in-situ adaptation measures are insufficient or remain unfunded (Boe Declaration, 2018; Nunn, 2013; Barnett et al., 2022).

While movement away from climate-impacted areas can often be achieved locally or within national borders, international migration can be a viable choice for some people whose livelihoods are drastically undermined by climate change.

These irreversible and reversible losses caused by climatic changes not only endanger Pacific peoples’ economic livelihoods but also their physical and mental well-being. Climate change-induced migration and displacement could lead to loss of unique ecosystems, fragmentation of communities, and erosion of social structures and relationships. Should residents be compelled to migrate, the damaging repercussions on their spirituality, identity, and security rooted in place could be profound. Loss and damage impacts are complex. Such non-economic loss and damage (NELD) or adverse impacts of climate change that cannot be easily quantified in financial terms, can have significant and lasting damages on communities.[1] Discussions on the impacts of NELD are highly pertinent to small island developing states that are threatened existentially by climate change.

A critical dilemma posed by climate-induced migration is the loss of land and cultural identity which can be considered a NELD often omitted from national planning. Throughout the Pacific region, there exists a profound attachment to ancestral lands and resources (Kempf & Hermann, 2014). This connection transcends the physical, intertwining the spiritual, emotional, social wellbeing and communal aspects of the Pacific peoples. In the Pacific, land is understood as “a living relational entity with strong spiritual elements which underpin an individual’s and group’s identity” (Campbell, 2024). Thus, the land possesses both a spatial and temporal meaning that reinforces people’s sense of belonging and connects current and future generations with the ancestors of the past. The Fijian concept of vanua exemplifies this, merging historical legacy with future potential (Ravuvu, 1983). Ravuvu articulates that land equates to life, and to part with one’s vanua is akin to parting with life itself (Ravuvu, 1983). Teaiwa also stresses that “Te aba,” which means both land and the people simultaneously in Gilbertese (the Kiribati language), is “an integrated epistemological and ontological complex linking people in deep corporeal and psychic ways to each other, to their ancestors, to their history, and to their physical environment (Teaiwa, 2015, pp.7-8). This intrinsic and inseparable connection to land that Pacific peoples value is now at grave risk due to climate change-induced migration and resettlement.

Studies by McNamara and colleagues have reinforced that, for Pacific Island communities, separation from their ancestral lands and relocation to new areas can entail numerous risks including intangible, non-material losses like the erosion of identity, social cohesion, traditional knowledge and customary practices inextricably linked to their natural environment (McNamara et al., 2021). “Losses to ecosystem services, environmental biodiversity due to climate change are closely linked to loss of land and have cascading effects on Pacific people’s livelihoods, indigenous knowledge, ways of life, wellbeing, culture and heritage” (Westoby et al., 2022).

Climate change-induced migration and displacement could lead to fragmentation of communities, and the erosion of social structures and relationships. In the Pacific, where traditional knowledge and practices are passed down through social networks, such disruptions can threaten the social and ontological security, emotional and spiritual wellbeing of Pacific Islands people (Farbotko, 2019; Boege, 2022; Campbell, 2024). Hence, the fear of losing connection to their ancestral land is a pivotal factor in Pacific Islanders’ reluctance to consider migration as a viable adaptation response to climate change.

It should be noted that for many in the Pacific, relocation is most likely to be local, occurring on land within the same vanua or fenua. This is especially true for community relocation of many coastal villages, such as in Fiji. Although this type of relocation results in less disruption to identity and culture, there are still typically negative effects (Boege & Shibata, 2020). Although the tangible economic impacts of displacement are well- documented, the intangible loss and damage experienced by climate migrants often remains overlooked (Chandra et al., 2023).

This study explores the experiences of Pasifika youth who have migrated internationally to countries such as Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the United States (Hawai’i). Although these atoll migrants have not necessarily experienced displacement or forced relocation due to or in anticipation of climate change impacts, some have undergone involuntary migration to different countries for economic reasons. Some of these young migrants have been involuntarily uprooted from their familiar Pacific cultural surroundings and forced to adapt to new environments. The study aims to learn from the experiences of these youth migrants in Western diasporas. It analyses the nuanced dimensions of intangible loss and damage faced by Pasifika young migrants as they navigate the critical emotional, cultural, and societal ramifications associated with the loss of connection to ancestral lands, cultural identity, indigenous knowledge, social cohesion and their foundational sense of self and belonging.

Method

The study explores, through the experiences of the young migrants who have settled in the Western diasporas, how migration may impact the connection to their cultural roots, and their sense of security and identity. While the participants in this study are not so-called “climate migrants or refugees” who have been forcefully uprooted from their lands, it has been repeatedly stressed by Pacific community leaders that there may be potential value in learning from the experiences of the Pacific migrants who have settled in foreign countries like Aotearoa New Zealand, or Australia.[2] Tammy Tabe (2022) further described the significant role of Pacific diasporas as “people that have gone before us to create those bridges and pathways so that the rest of us can have an easier way to travel to other parts of the world.”

Our exploratory research sought to comprehend the individual and shared experiences of young Pasifika migrants as they navigate their migration journeys in foreign lands. The narratives of these youths offer significant insights into the critical hurdles and challenges that may confront future climate-induced migrants, as well as the host communities that will face the possibility of accepting a substantial influx of new settlers.

“…for Pacific Island communities, separation from their ancestral lands and relocation to new areas can entail numerous risks…like erosion of identity, social cohesion, traditional knowledge and customary practices inextricably linked to their natural environment.”

Talanoa, a traditional dialogue process in the Pacific Islands, was selected as research methodology. Talanoa is deeply rooted in the Pacific Island cultures and embedded in a communal form of storytelling, sharing of wisdom, and cultivation of mutual understanding (Farrelly & Nabobo-Baba, 2014; Vaioleti, 2006). By utilising Talanoa as a methodology, this study ensures the representation of Pacific viewpoints and psychologies, encourages cultural sensitivity, and meaningful engagement to draw lessons from the Pacific youth migrants. This approach resonates with the cultural principles of respect, reciprocity, relationality and engagement which are foundational to Pacific cultures (Vaioleti, 2006). The research was qualitatively designed to use group-based Pacific storytelling to extract rich and frank narratives that reveal the real experiences, perspectives, and insights of the youth migrants.

The selection of participants was guided by purposeful sampling to ensure a comprehensive spectrum of youth migrant experiences. Participants were identified through the assistance of key informants within the respective diaspora communities in the host countries, community partners and stakeholder organizations. Researchers valued community engagement and participation as central components of the research process. We gained formal consent from the leaders of the diaspora communities and tried to establish meaningful relationships with them. We encouraged the youth climate activists and community leaders’ active participation in shaping the research questions and findings. By incorporating their input, the intention was to instill a shared sense of ownership, thereby enhancing the authenticity and relevance of the findings.

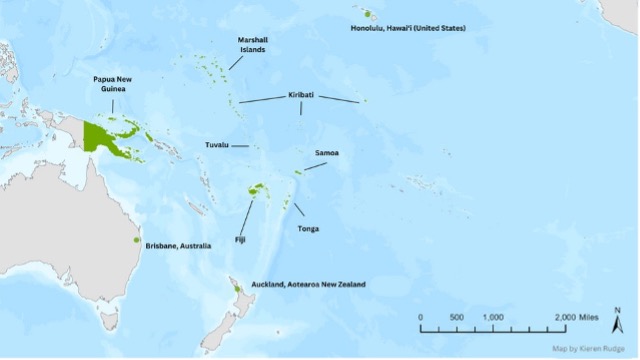

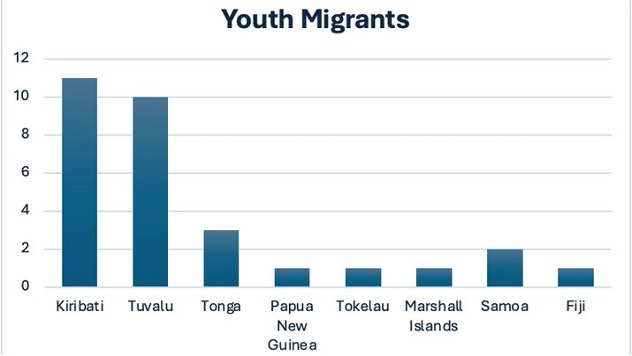

During the period of 3 August to 3 October 2022, a series of twelve Talanoa mix-gendered sessions were conducted to explore the journeys of 30 Pasifika youth migrants residing in Western diaspora communities. To allow for in-depth sharing of their stories, each session was comprised of 2-4 participants. The participants in the Talanoa sessions were selected from diverse Pacific diaspora communities of Kiribati, Tuvalu, Samoa, the Marshall Islands, Tonga, Papua New Guinea, Tokelau and Fiji residing in Auckland and Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand; Brisbane, Australia; and Honolulu, Hawai’i (see Table 1 for the breakdown). The participants consisted of 21 females and 9 males (n=30), with ages ranging from 19 to 33 years old (mean age = 24.5). The majority of the Talanoa sessions were hosted in culturally appropriate Pacific settings such as local churches and community centres in the diasporas, with five sessions facilitated online via Zoom. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the study and pseudonyms were assigned to each participant in order to ensure anonymity and confidentiality of their identities. Ethics approval was obtained from Toda Peace Institute in August, 2022 (TPI101). The conversations were structured around open-ended questions, prompting participants to provide candid reflections on their migratory experiences. Many of the young participants in these sessions had relocated to diaspora communities early in life and were thus at ease discussing their experiences in English. When necessary, language support was provided by community leaders, ensuring effective communication throughout the discussions.

Talanoa sessions were video- or audio-recorded with prior consent from the participants to ensure accurate and detailed transcription production and analyses. As recommended by Farrrely and Nabobo-Baba (2012), efforts were made to create a respectful and empathetic atmosphere to encourage Pacific participants to comfortably share their stories and experiences. The researchers attentively listened, periodically asking for clarifications to promote reciprocal dialogue to deepen mutual trust and understanding. In the analysis phase, the researchers engaged in reflective discussions with key interviewees to ensure an accurate interpretation of their accounts.

The overarching goal of this research was to glean insights from young Pasifika migrants to inform policy development, decision-making, and resource allocation strategies pertinent to future climate-induced migration and relocation from Pacific Island nations. By understanding the lived experiences and hurdles faced by these migrants, policy makers and stakeholders can develop a more comprehensive and holistic perspective on the complexities associated with Pacific migration, leading to more inclusive interventions in the future.

Findings

In this study, we explored the dynamics of intangible losses among Pasifika youth who have migrated to predominantly Eurocentric host societies such as Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the USA. Through coding and meticulous data analysis, we uncovered the following key themes that underpin the migrant experience of these individuals.

Loss of land and identity:

Our findings illuminate a profound sense of loss among the youth, particularly those with extensive childhood experience in the Pacific islands. They articulate a deep-seated connection to their ancestral lands which is intrinsic to their identity and sense of belonging.

Difficulty of navigating multiple identities in the process of acculturation:

The journey of acculturation presents a complex challenge, as these young individuals grapple with the task of reconciling their Pacific heritage with the norms of their new Eurocentric environments. This process often requires them to negotiate and navigate multiple, often conflicting, identities.

Confronting racism, discrimination and wounded dignity:

Our study also exposes the painful reality of racism and discrimination faced by Pacific youth in their host societies. These experiences have not only hindered their acculturation process but also inflicted wounds upon their dignity, with long-standing implications for their emotional well-being.

Climate victimhood:

Although the participants were not “climate migrants,” they nonetheless expressed a unique and ongoing sense of injustice associated with the climate crisis, which disproportionately affects their own homelands. However, they resist the common victimhood narrative of being labelled as the helpless people from the sinking islands.

Community engagement and social cohesion:

Despite the challenges, there is a silver lining in the form of active community engagement. Many youth find solace and strength in social cohesion, often facilitated by community groups that provide a sense of familiarity and cultural continuity in their new settings.

Nurturing cultural identity through climate activism:

Climate activism has emerged as a pivotal avenue for some youth to reconnect with their cultural roots. Through advocacy and activism, they not only contribute to the global fight against climate change but also reclaim and reinforce their own Pacific identity.

“I have accepted over time that our islands are not going to be saved…I worry about the burial grounds where our ancestors lay to rest. That is our connection to the past, present, and even the future.” Taianui, Kiribati

LOSS OF LAND AND IDENTITY

Youth who have spent a large part of their upbringing in the Pacific islands were particularly challenged by the loss of ties with their indigenous heritage and stressed the meaning of land in their lives. Taianui is from Kiribati and moved to Aotearoa New Zealand to receive a university education. After his scholarship, Taianui plans to return to Kiribati to share his migration experience with other youth who are interested in relocating to other countries. In his poignant narrative, Taianui stresses the intrinsic bond Pacific Islanders have with their land and ocean—a bond that transcends time, linking past, present, and future. This profound connection serves as the cornerstone of his identity, a stable anchor amidst the waves of change in his new environment. The potential risk of loss of land caused by climate change has left many Pacific youth yearning to preserve their link to their ancestral lands. The prospect of its severance instills in them a deep sense of anxiety and unease.

“I grew up on an island surrounded by the beautiful sea…. I have accepted over time that our islands are not going to be saved. There isn’t much action going on around the world to stop it [climate change]. If we lose our lands, we still have the ocean. However, I worry about the burial grounds where our ancestors lay to rest. That is our connection to the past, present, and even the future.” (Taianui, Kiribati)

Young migrants from Kiribati, Mahina and Tamaeva’s words convey the turmoil of emotions that the thought of losing their land evokes. Mahina likens the potential loss of her homeland to the heart-wrenching grief of losing a grandmother—the matriarch of her family and the living embodiment of her lineage. For Tamaeva, the land is much more than a mere physical space; it is the repository of her history, a spiritual anchor and a source of heritage and continuity. The fear of this loss is not just about displacement, but a disconnection from the essence of her being, the cultural and familial roots that define who she is.

“So, losing Kiribati is like losing my own grandmother. My connection to my roots has always been through my grandmother… I know we carry culture with our bodies… but … I will feel like sort of lost…. I can never picture a life where my grandmother wouldn’t be there…. You know, you just feel so incomplete. You kind of feel empty in a way. When I feel insecure [being away from home], I always think of her. I try to remember about the certain traditional practices that she would teach me. Losing my connection to the land is like losing my grandmother. It’s like loss of a close family…” (Mahina, Kiribati)

“If we are ever forced to relocate because of climate change… we cannot abandon our land because our ancestors are buried there. Can we really abandon the bones of our ancestors? That is hard for me to imagine...” (Tamaeva, Kiribati)

The collective voice of the Pasifika youth thus underscores the deep-rooted understanding that their land is far more than a utilitarian source of livelihood but an important source of spiritual, emotional and social well- being. The potential loss and separation from these sacred grounds represent not just a change in geography but a fundamental disruption to their Pacific way of life. They make it clear that land is the cornerstone of their identity and a non-negotiable element that defines their Pacific selfhood.

NAVIGATING MULTIPLE IDENTITIES

The exploration of identity among youth migrants presents a complex process of cultural adaptation. While a segment of these youth individuals migrated for higher education purposes, a significant number were either born in host countries or had relocated from Pacific islands with their families during their formative school years. [3] Each participant in the study revealed the challenges and intricacies involved in managing multiple cultural identities amidst the processes of adaptation and integration into their new host societies (Manuela & Anae, 2017; Berry et al., 2006).

For many youth migrants raised in predominantly Eurocentric environments, preserving their Pasifika identities became a challenging aspect of their acculturation and societal integration. As they became older, these individuals felt a stronger need to rediscover their cultural roots, spurring their desire to re-engage and reconnect with their Pacific identities. Nonetheless, their journeys also include moments of conflict where they experienced pressure to suppress or to downplay their Pasifika identities in order to conform and “fit in.” Alani, a Marshallese migrant, recounted the struggles her family endured in their attempts to blend into the Hawai’ian community. Laveni, a Tongan raised in Aotearoa New Zealand, also shared her complex journey having to balance multiple cultural identities as a Pacific migrant. These personal testimonies underscore the dichotomy faced by many youth migrants as they navigate the dual desires of fitting in and preserving their unique cultural heritage.

“As I grew older, my parents started to prioritize speaking English in our home and at school. They put more emphasis on our education and put culture in the background. As new immigrants, our community faced many challenges and struggles because people had misconceptions about Micronesians and the Marshallese people. I felt the need to tone down my Marshallese-ness…. Because of these microaggressions, I felt like I was forced to be ashamed of who I am. I constantly had to ask myself, ‘Am I Western enough?’ ‘Am I good enough to be accepted and fit into this society?’….We are taught to put aside our own cultural views and prioritize the Western way which is very different… As I was growing up, I would even complain about or make fun of a lot of things about my culture. Later on, as I grew up, I had to decolonize myself and reappreciate my culture.” (Alani, the Marshall Islands)

“I identify myself as a Christian and a Tongan person living in New Zealand diaspora, but not a Tongan from Tonga. …As a member of the diaspora, I represent a mix of different cultures, identities, and ideas…and that determines how I manage my identity and act depending on different spaces. I moved to New Zealand from Tonga when I was three. I went to a private school, and I was basically the only brown person there. In that space, for a long time, I rejected and abandoned my Tongalese-ness.

Maybe it is because of the history of dawn raids[4] and the attitudes towards Pacific Islanders in Aotearoa. Nonetheless, my parents always encouraged me to be who I am and embrace my Tongalese-ness. I acted differently in the two cultural spaces …. But I felt like I wasn’t good enough in either of these spaces…I went through insecurity and there was a lot of unpacking and healing to do and reclaim my own Tongan identity growing up in New Zealand.” (Laveni, Tonga)

Napo’s narrative provides a compelling insight into the complexities of identity for i-Kiribati youth in the multicultural landscape of Aotearoa, New Zealand. This environment, rich with diverse Pasifika communities[5] sets the stage for intricate identity negotiations. Napo encountered a predominant Samoan presence in his school, which influenced his choice to adopt a Samoan identity, sidelining his i-Kiribati roots. His family’s emphasis on assimilation—speaking English and integrating into the local culture—also steered Napo away from his heritage. However, he stated that as he grew older, his yearning to reconnect with his true cultural roots became stronger.

“I moved to New Zealand as a kid. When people asked me, ‘Where are you from?’ I wouldn’t say I am from Kiribati, I’d say I am Samoan because majority of the Pacific people around me were Samoan, and I wanted to fit in. Also, I didn’t know much about my Kiribati culture. I think my family played an influential part in this. My grandpa who raised me when we moved to New Zealand, would say, ‘Hey, I don’t want to you to speak in Kiribati, I want you to speak English. I want you to find a White wife.’ This changed my perspective as a kid. I didn’t want to learn Kiribati, I wanted to learn English. I wanted to be part of the Kiwi culture. But then, you get to a point in life where you want to rediscover your own culture, learn about your culture and I actively sought to reconnect with my Kiribati identity. However, I was told that ‘you’re not Kiribati enough.’ But then, … I will never be Kiwi enough. So yeah, that’s how I went through an identity crisis. I had to go through a challenging journey of rediscovering my Kiribati identity where my faith played a huge role.” (Napo, i-Kiribati)

“Because of these microaggressions, I felt like I was forced to be ashamed of who I am… ‘Am I Western enough?’ ‘Am I good enough to be accepted and fit into this society?” Alani, the Marshall Islands

Napo’s journey highlights the pivotal role of faith and spirituality in self-reflection on his cultural identity. His experience is not an isolated one among Pasifika youth migrants, who often rely on Christian faith as a cornerstone for overcoming their identity crises and rediscovering their sense of belonging.

Teuila is a Samoan young woman who spent her school years in Australia and the United States. She brings attention to the critical challenge encountered by many youths who have migrated to Western societies—the process of mental decolonization. She argues for the need to transform the internal colonial mentality that can dominate the psyches of youth migrants, fostering a sense of ethnic inferiority. She strongly advocates for the Pacific youth to shed this colonial mindset and to affirm their unique cultural worth.

“I really want to make sure that the young Pacific migrants don’t experience the same struggle I went through. I am talking about the process of internal colonization. You start to think and behave like the colonizer because you grew up in the West and because of the education that was forced upon you. We have to change our colonial mentality and overcome our sense of cultural inferiority.” (Teuila, Samoa)

These personal accounts shed light on the broader narrative of Pasifika identity formation in Western diasporas, influenced heavily by colonial legacies. The negotiation and construction of a decolonized identity are essential in combating internalized racial oppression. Past studies have indicated that internalized racial oppression and colonial mentality can have negative effects on the mental wellbeing of the migrants (David & Okazaki, 2006; David & Nadal, 2013). Addressing these issues of identity and mental wellbeing is an important responsibility for host societies, as they navigate the delicate process of supporting migrant communities in their quest for cultural affirmation.

MICROAGGRESSIONS, DISCRIMINATION AND WOUNDED DIGNITY

The stories of Pacific youth migrants in nations like Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the United States bring to the forefront a pressing global issue that extends beyond their individual experiences—an intangible damage like wounded dignity and self-respect that climate migrants may increasingly encounter in the future. As they juggle multiple cultural identities, they often confront subtle yet pervasive forms of discrimination and microaggressions in their host countries. These microaggressions are, by their nature, indirect and frequently unintentional slights that nonetheless convey demeaning and hostile undertones towards members of marginalized groups. They can take the form of stereotypes, which are oversimplified and generalized beliefs about a group of people that can lead to prejudiced attitudes and behaviors (Kite et al., 2022). Stereotyping and cultural insensitivity towards Pacific migrants perpetuate harmful and inaccurate perceptions of their culture, intelligence and capabilities, making their journeys even more difficult. In Hawai’i, for instance, stereotypes about Micronesians and Marshallese are particularly stigmatizing. The community is often depicted homogenously, with gross generalizations about their living conditions, and the behavior of their youth. Alani from the Marshall Islands articulates the humiliation that comes from such generalization often portrayed in the US media. Alani emphasizes the personal struggle to demonstrate her individual worth and competence.

“Stereotyping is very common here (Hawai’i)….It is humiliating to be imitated. They say Micronesians and Marshallese live together, like sixteen people in an apartment. They therefore don’t take care of their environment. Or Micronesian kids don’t go home on time. They’re always running around like hooligans and… get involved in violent crimes. These are the common perceptions about us that are reported in the media. I had to always fight to prove to them that I am not like that, and that I am capable” (Alani, Marshall Islands)

The complex interplay of stereotyping and microaggressions extends beyond simplistic notions. They can manifest as insensitive remarks about physical appearance or about language proficiency, contributing to a deep sense humiliation, marginalization, and exclusion. Alani’s story sheds light on the subtle yet demeaning practice of exoticization where Pacific migrants are frequently seen as exotic curiosities. The implication that being ‘smart’ or ‘pretty’ is an exception within their community is not only offensive but also reinforces damaging stereotypes that suggest uniform lack of intelligence or beauty among Micronesians.

“We are not drowning. We are not going to disappear. And we don’t want to be climate refugees. We don’t want to be pitied and we are not helpless.” Mahina, Kiribati

“I hated it when people say, ‘Oh, you are smart for a Micronesian,’ or ‘You are pretty for a Micronesian.’ You know, it’s like a backhanded compliment implying that, ‘your people are not usually smart or beautiful…. I always felt like a ‘token brown person.’ I felt like an imposter that didn’t fit in, so I had to adjust myself to fit in—and that made me feel so insecure.” (Alani, Marshall Islands)

Microaggressions can be frequently expressed in the form of commentary on language skills, where even a compliment can be tainted with racist undertones. Ailana from Tuvalu shares her frustration over the surprise expressed by others at her language proficiency. These seemingly innocent questions are a form of ‘othering’ that can lead to feelings of objectification and reinforce the notion that Pacific Islanders are perpetually foreign and ‘different’ from the dominant culture of the host societies.

“I am often asked, ‘Wow, where are you from? You speak well enough’ or ‘Where are you really from?’ These questions make me feel like I really don’t belong.” (Ailana, Tuvalu)

Pacific youth migrants also encounter biases in educational settings. Low expectations from teachers can be detrimental to their sense of dignity and academic aspirations. Emele moved to Auckland from Kiribati when she was in high school to pursue her college education in New Zealand. She recounted, with tears of pain and humiliation, her experience with her college supervisor who made dismissive and demeaning remarks about her competency which deeply hurt her self-esteem. These encounters can have long-term damages on the young students’ sense of self-worth.

“I started university…and I really wanted to pursue accounting. But the teacher told me that I was not competent enough. She said, ‘Oh, your English is not good enough.’ There is no respect for Pacific Islanders. We have to deal with this stereotyping that we’re not good enough. They think we are not going to be successful in life anyways. They always see us like we’re going to do small, menial jobs.” (Emele, Kiribati)

Amoe is an i-Kiribati migrant who volunteers to offer pastoral care for young ones. She emphasises the danger of seeing microaggressions and discrimination against them as becoming normalized.

“The older ones will look after the younger ones at school. We are there, so that if the young ones are in trouble, they can come straight to you. There was this young boy that we were taking care of. When we first asked him if he ever experienced racism in school, he said no. And then when we gave him some examples, he said, ‘Oh, if so, yes, I have experienced that.’ We felt it is really sad that racism has become so normalized among young people and they don’t even realize that they have been mistreated. They think it is normal for Pacific Islanders to be treated that way.” (Amoe, Kiribati)

Microaggressions in educational settings can be very subtle and often go unnoticed by teachers and other classmates but are powerful enough to undermine the young migrants’ sense of security.

“I am a female Pacific Islander and as a female, already I face many inequities and on top of that, I am a woman of color from the Pacific. That is another layer of discrimination. I am constantly having to prove to others that I am competent, or at least, that I can do the same thing that they can do. In my master’s course, I had to do a group project with two other Kiwi boys. When it was time to discuss things, they just kind of ignored me and started talking among themselves. This made me feel so insecure.” (Langi, Kiribati)

When Langi’s presence was dismissed by her peers, the exclusion not only undermined her value in the classroom, but also instilled a profound sense of insecurity and doubt in her own abilities. These microaggressions force Pacific students like Langi to continually assert their competence and fight for their place in educational and professional settings in the host countries.

CLIMATE VICTIMHOOD AND SINKING ISLANDS

Added to the challenges to their sense of dignity and lack of recognition in host countries, the precarity of climate change and the possible loss of islands have generated an unwanted victim narrative that the youth migrants strongly reject.

“My island is becoming more and more famous because of climate change these days. I am often asked by white students, ‘Where are you from?’ And I answer, ‘Kiribati.’ And the first thing they say is, ‘Oh, that sinking island!’ I hate to be labelled like that. I want them to treat me with more respect.” (Taianui, Kiribati)

“We are not drowning. We are not going to disappear. And we won’t be climate refugees. We don’t want to be pitied and we are not helpless.” (Mahina, Kiribati)

The narrative of victimhood associated with climate change is a significant source of distress for some Pacific youth migrants. They are frustrated by the pervasive media narrative that emphasizes the vulnerability of the Pacific Islands to climate change. They feel that such representations overlook the strength, resiliency and agency of the Pacific Island communities. Taianui and Mahina’s words reflect their concern that the dramatic representations of sinking, drowning islands lead to skewed public perception of small, low-lying atolls like Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Marshall Islands. This may further contribute to the stereotype that the migrants are striving hard to overcome. The label of “climate refugee” not only represents lack of agency and physical loss of land, but also the potential obliteration of their proud way of life and rich cultural roots.

These concerns expressed by Taianui and Mahina underscore a critical issue—the need for a more nuanced understanding and representation of Pacific Island communities in the face of climate change, one that acknowledges their resilience and complexity of their experiences rather than reducing them to helpless victims of environmental crises.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SOCIAL COHESION

Whilst navigating through the challenging journey of land loss, identity crisis and wounded dignity, many youth reach a point of realization that, in order to find peace and healing, they need to rediscover their roots and reconnect with culture. Physical separation from their home islands can lead to a fragmented sense of belonging, prompting these young individuals to seek solace and support within the Pacific diaspora communities. In host countries, these diaspora communities assume a vital role in sustaining the cultural and community life of Pacific Islanders abroad (Benjamin et al., 2019). They provide a space where cultural traditions are preserved and celebrated, and where the community can gather to mark life’s milestones and practice their customs.

“I participate in community gatherings that take place almost every weekend. It could be a birthday, a wedding, etc. It helps me reconnect with my own identity as a Tuvaluan and makes me feel secure.” (Ahulani, Tuvalu)

As Ahulani from Tuvalu stresses, engagement with diaspora communities enables them to reaffirm their heritage and reinforce their sense of self. Moreover, these diaspora communities foster social cohesion and provide a vital network for Pasifika migrants to replant their roots in new soil. The Elders within these communities are particularly crucial, serving as custodians and conveyors of indigenous knowledge and heritage. In places like Auckland, young women take an active role in preserving Tuvaluan culture by volunteering to teach the language to younger generations. However, challenges remain, as Ahulani notes a disheartening lack of interest among young Tuvaluans in Aotearoa New Zealand to learn and maintain their traditional language. This apathy towards cultural education could pose a threat to the continuity of their cultural legacy.

“Some young people are more interested in adopting the Palagi (white) culture and become accepted in the New Zealand society. Because they are not fluent, they feel shy and ashamed to speak the language. Their accents are not native, and that makes them even more reluctant to speak our language…I helped produce children’s books so that our children can start learning at a much younger age. Speaking the language is an important part of our own identity.” (Ahulani, Tuvalu)

“Some of our Tuvaluan youth go back home to visit their families but there are some challenges. Because they are not fluent, they feel like they are not accepted by the Tuvaluan home community. This is sad. So we ask other children not to laugh or make fun of mistakes. I want young people to be proud of who they are.” (Malana, Tuvalu)

Another participant spoke about the harsh working conditions and economic factors that hinder the parents in the diasporas from taking the time to teach culture and language to the younger generations. This is a concern that highlights the importance of intergenerational engagement and the need for innovative approaches to make cultural education appealing to the youth.

“To understand and speak the language is an important part of knowing who you are. But our parents are desperately trying to make their living in New Zealand…They are busy, and they come home tired and really have no time to teach their children culture and language.” (Ahulani, Tuvalu)

The stories in the diasporas also shed light on yet another challenge for the second generation Pasifika migrants in their struggle to maintain their cultural identity. While navigating dual identities living in the diasporas, Fiafia reveals that youth migrants are confronted with a sense of exclusion from the Pacific home communities due to their lack of indigenous traditional knowledge and language proficiency.

“When I visit my extended family in Tokelau, people can immediately tell that I am not from the homeland, mainly because of my accent and behavior. They say I am ‘plastic’, meaning I am not authentic.” (Fiafia, Tokelau)

RELEARNING AND RECLAIMING CULTURAL IDENTITY THROUGH CLIMATE ACTIVISM

Young Pasifika migrants who have relocated to Eurocentric societies are confronted with numerous obstacles that strike at their self-esteem and self-worth. However, their stories are not solely defined by adversity; they also encompass tales of resilience and inner strength. A key aspect of their fortitude is their engagement in civil society activities, particularly those advocating for the Pacific region, such as climate justice initiatives. The quote from Laveni of Tonga highlights the transformative impact that climate activism has had on her personal journey of cultural reclamation. For Pacific youth, leading social justice movements for their people is a pathway to self-empowerment. It is within these movements that they find a supportive community, one that respects and celebrates their heritage, enabling them to embrace their Pacific identities with pride.

“My climate activism has really helped me reclaim my cultural identity. These social justice movements are led by Pacific youth and empower us to reconnect with who we truly are. It is a community that is safe and allows us to be proud of who we are...” (Laveni, Tonga)

Further illustrating this point is the collective action of Pacific youth from diverse nations who are uniting to heighten global consciousness about climate threats facing the region. They are actively lobbying world leaders and corporations to cut down on carbon emissions. This collective advocacy serves not only as a means of representation for the Pacific region but also as a vital avenue for diasporic youth to rediscover and reassert their cultural identities (Farbotko & McMichael, 2019). The activism against climate injustice provides them with the means to challenge and reshape prevailing narratives about Pacific Islanders being passive victims of climate change, and instead emphasise their role as ‘proactive, and self-determining agents of change’ (Dreher & Voyer, 2015).

“When I look at our role in this international space, it is to show the world what sustainable development really looks like, weaving in ecology, theology, faith and culture. How the Pacific can lead the way in all of this? Pacific can be instrumental in setting the foundation for a lot of the climate justice policies and frameworks…I’m really proud of the Pacific youth, young women, who understand this and will continue to keep on working until the world changes.” (Tiare, Marshall Islands)

“My climate activism has helped me reclaim my cultural identity…It has led us to reconnect with who we truly are…and allows us to be proud of who we are.” Laveni, Tonga

Simultaneously, the youth activists described the struggle for climate justice as emotional and onerous work that could be ‘depressing’ and could lead to ‘burn-out’. Alani described her struggles as a young Pacific activist confronted with tokenism at international climate conferences. Even if the youth voices are invited to present at global conferences like COP, Pacific youth activists are often tokenized by being given symbolic roles without genuine engagement with the decision makers; their narratives are scripted, their contributions controlled and their impact is diluted. This leaves the young activists feeling exploited and undervalued.

“I think indigenous voices are very strong. But we are not being invited to the table. We are just there to tick the box. They invite us to speak about our experiences, but then they give us a script to read.” (Fiafia, Tokelau)

“Climate change work is going to be a long game…and it comes with a lot of shackles like tokenism and Pacific exoticism. People think that I’m like Moana and I go sailing every day. And there are people who just straight up exploit our presence just to say they’ve done something.” (Tiare, Marshall Islands)

“As a young Pacific leader, it takes a lot of courage to remain active in this space. I am not an expert. Am I qualified to speak on this issue? I just think, if I tell the truth, I never have to worry what I’m saying. Because it is the truth. Because I have seen it happen at home, in my community. Their lived experiences are real, and no one can take that away from them. So, we just have to keep on pushing through every storm, or in Marshallese, kurtoplok, point of no return. No matter how hard, you’re not the only canoe out there sailing. All of us are sailing together and we have that solidarity.” (Tiare, Marshall Islands)

The sentiments of the Pasifika youth underscore a sobering reality: despite the urgency of their message and the authenticity of their voices, they often confront the disheartening practice of tokenism. More efforts should be made to promote meaningful engagement with Pasifika youth to recognize and reflect the needs, fears and concerns of the young people in the global policy discourse. The voices of the Pacific youth represent the frontline experiences of climate change driven loss and damage. The active participation of Pacific youth in global conferences should not be a tokenistic courtesy—but be treated as a critical necessity.

Discussion & Recommendations

DETACHMENT FROM LAND AND LOSS OF IDENTITY

The migration stories of the Pacific youth highlight how future climate mobility to foreign lands can precipitate a cascade of serious non-economic losses that are difficult to quantify but have profound consequences for Pacific Islanders’ holistic well-being. The narratives of the youth migrants reinforced past studies that demonstrate how loss of ancestral land and burial sites, cultural identity and traditional indigenous knowledge all cut to the core of the Pacific identity and ‘ways of being’(Ravuvu 1983; Kempf & Hermann 2014; Campbell 2024).

Participants stressed that land is not just a habitat but a central pillar of heritage and spiritual link to who they are, likening the island to their own grandmother who they cannot imagine being disconnected from. Losing one’s sense of belonging could be a source of distress and emotional burden for Pacific migrants. From this perspective, our findings underscore the importance of addressing the intangible impacts of loss of identity and security caused by detachment from land when considering future plans for adaptation and Pacific climate mobility (Adger et al., 2011).

DEALING WITH EROSION OF DIGNITY AND SELF-ESTEEM

Racial discrimination and stereotyping:

The youth migrants face the difficult task of maintaining, reclaiming and restoring their cultural identity while adapting to new environments. Their narratives reveal that this process is complicated by the need to negotiate their self-concept in a setting that may not value or understand their heritage. Almost all the youth migrants in the study mentioned that they frequently encounter racial discrimination, stereotyping and microaggressions. Such harmful behaviour can lead to wounded self-esteem, anxiety and psychological stress which are significant barriers to successful integration.

Need for a safe environment:

The study underscores the importance of creating a safe space in which migrants can experience cultural freedom and maintain their unique identities. Combating everyday racism in a society is indeed an ongoing onerous task.

Diversity education:

One proactive approach to facilitate better integration is through diversity education. The incorporation of Pacific histories and cultures into the host countries’ education curriculum can promote greater understanding and appreciation of Pacific Island cultures. This can help dispel long-held misconceptions and stereotyped images of the Pacific Islanders.

Cultural competency training:

There is a need for systematic cultural competency training and exchange programs with Pacific peoples within schools and communities. Such initiatives can bridge cultural divides, transform perceptions and generating more inclusive behavior and respectful engagement with the Pacific migrants.

It is essential to address the systemic nature of racism and the role of institutions in perpetuating discrimination and promoting narratives that would encourage stereotyping. By advocating for educational reforms, cultural exchanges, and competency training, the study calls for a holistic and sustained approach to support the well-being of Pacific migrants and ensure their healthy integration into new societies.

DIASPORA’S ROLE IN HELPING YOUTH REGROW THEIR ROOTS

Although the youth felt that their migration journeys have been full of pain and obstacles, the Pacific stories have exhibited a remarkable capacity for resilience and hope in the face of challenges to their dignity and identity. Many Pacific youth participants have proudly shared their stories of successfully reclaiming and restoring their Pacific roots. Pacific diaspora communities are dynamic spaces where cultural practices are not only preserved but also transmitted to new generations. Elders play a pivotal role in this process, acting as the repositories of indigenous knowledge and tradition, bridging the past and the future.

Support from host countries:

It would be ideal if the host countries could offer financial support and resources to the diaspora communities so they can act as a catalyst for innovation within tradition. Initiatives such as cultural festivals, language education support and collaborative projects can help to rekindle interest and participation of youth. Diaspora communities play an integral role in helping preserve indigenous knowledges, languages and cultural heritages. Establishing safe spaces, support networks and community organizations that offer resources and advocacy for Pacific migrants can be crucial in alleviating the impact of racism in the recipient communities. Diaspora communities are vital for cultural continuity as they provide a ‘fertile soil’ for connecting the migrants to their roots and regrowing a sense of belonging (Yates et al., 2023). For this reason, the study stresses the need to amplify the voices and involvement of Pacific diasporas as well as local indigenous communities in the policy development and implementation of relocation schemes. This will ensure that a holistic Pacific approach is incorporated in the planning stage and disruption of the existing socio-cultural traditions is mitigated (Boege, 2018).

Early planning and consultation:

The study recommends early planning and consultation between migrating communities, diasporic communities and recipient communities (Campbell, 2024). For example, the Falepili Union Treaty (2023) between Tuvalu and Australia, promising a new climate migration pathway for Tuvaluans to work and live permanently in Australia, has been the subject of significant controversy and criticism because of the lack of consultation with the Tuvaluan people (Sopoaga 2023). Furthermore, concerns have been raised by Tuvaluan activists that the framing of the migration pathway in the treaty as a climate solution reinforces the notion of Tuvaluans as ‘climate refugees’ or ‘climate migrants’ which could lead to discrimination and even be seen as ‘an insidious form of colonialism’ (Kitara & Farbotko 2023). Some i-Kiribati participants strongly urged in the talanoa that early exchanges between migrating and recipient communities can lead to a more culturally-sensitive relocation scheme that respects the intangible needs and values of both the migrants and the host community.

Conclusions

This study brought to light the many non-material losses and challenges that Pacific migrants experience when they migrate internationally. The stories of the young Pacific migrants have revealed that intangible assets such as cultural identity, dignity, and sense of belonging are as vital as quantifiable economic resources. The plight of Pacific youth illustrates a glaring oversight in current climate mobility policies, which largely ignores these crucial aspects of holistic human well-being. The experiences of Pacific youth in foreign host countries tell us that for future climate migrants, relocation will not be just a move from one place to another; it will become a traumatic uprooting of life itself, with deep psychological, social, and cultural ramifications. Non-economic loss and damage extends beyond the cost of rebuilding homes or restoring infrastructure. It’s about the loss of ancestral burial sites that lie submerged, the fading away of indigenous knowledge, and the disintegration of social cohesion as communities are forced to scatter to different locations.

The global community and climate change policy makers need to acknowledge that displacement and relocation due to climate change is not just a physical loss of place but is deeply entangled with loss of cultural identity, spirituality and relational security for the Pacific peoples. Hence, an international policy mechanism for loss and damage needs to broaden its framework to encompass the holistic impacts of climate change and consider the risks of non-economic losses of affected communities and populations when they are forced to separate from their home islands. A recent study on climate-induced non-economic loss and damage (NELD) in Pacific Small Island Developing States (Chandra et al., 2023, p. 22) has concluded that “despite best efforts to progress pre-emptive adaptation and risk reduction responses to address climate risks, policy responses to NELD remain largely unaddressed and poorly understood by Pacific Island countries.”

It is within this context that the voices of the Pacific youth migrants should be carefully listened to by policy makers of Pacific Island nations as well as potential host countries such as Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the United States. The stories shared by the Pacific youth deepen our understanding of the consequences of losing their ties to their ancestral lands and experiencing the erosion of their dignity as they deal with loss of cultural identities. The insights of young Pacific climate activists must go beyond symbolic participation. It is time for the global community to earnestly integrate the experiences of Pacific youth in the decision-making process, making sure that their involvement is not mere tokenism. The stories of the youth migrants shed light on the weakness of the current international legal framework that fails to capture the grief felt by the affected communities and younger generations witnessing the loss of their sacred sites. By understanding the depth of such non-material impacts of migration, we hope that the host communities as well as global stakeholders can provide support to recognize the rights of future climate change-related migrants to protect their cultural values, identity and way of life.

References

Adger N. W., Barnett J., Chapin, III F. S. & Ellemor, H. (2011). This must be the place:

Underrepresentation of identity and meaning in climate change decision-making. Global Environmental Politics, 11(2), 1-25.

https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00051

Anae, M. (2020, October 18) The terror of the dawn raids. E-Tangata.

https://e-tangata.co.nz/history/the-terror-of-the-dawn-raids/

Barnett, J., & Campbell, J. R. (2010) Climate Change and small island states: Power, knowledge and the South Pacific. London and Washington, DC: Earthscan.

Barnett J., Jarillo, S., Swearer, S. E., Lovelock, C. E., Pomeroy, A., Konlechner, T., Waters, E., Morris R. L., & Lowe, R. (2022, May 16) Nature-based solutions for atoll habitability.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0124

Benjamin, L., Thomas, A., & Stevenson, M. (2019) Non-economic losses and human rights in small island developing states. In M. Faure (Ed.), Elgar Encyclopedia of Environmental Law. (pp. 494-504) Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (Eds.). (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780415963619

Boe Declaration (2018, September 6) Forty-Ninth Pacific Islands Forum, Boe Declaration on Regional Security. Available at: https://www.forumsec.org/boe-declaration-on-regional-security/

Boege, V. (2018, July) Climate change and conflict in Oceania: Challenge, responses, and suggestions for a policy-relevant research agenda. Toda Peace Institute Policy Brief no.17, Tokyo: Toda Peace Institute.

https://toda.org/policy-briefs-and-resources/policy-briefs/climate-change-and-conflict-in-oceania-challenges-responses-and-suggestions-for-a-policy-relevant-research-agenda.html

Boege, V., & Shibata, R. (2020, November). Climate change, relocation and peacebuilding in Fiji: Challenges, debates, and ways forward. Toda Peace Institute Policy Brief, no. 97. Tokyo: Toda Peace Institute.

https://toda.org/policy-briefs-and-resources/policy-briefs/climate-change-relocation-and-peacebuilding-in-fiji-challenges-debates-and-ways-forward.html

Boege, V. (2022) Ontological security, the spatial turn and Pacific relationality Part I. Toda Peace Institute Policy Brief, no. 123. Tokyo: Toda Peace Institute.

https://toda.org/policy-briefs-and-resources/policy-briefs/ontological-security-the-spatial-turn-and-pacific-relationality-a-framework-for-understanding-climate-change-human-mobility-and-conflictpeace-in-the-pacific-part-i.html

Campbell, J. R. (2024) Climate change, migration and land in Oceania. In R. Shibata, S. Carroll, & V. Boege (Eds.) Climate change and conflict in the Pacific: Challenges and responses (pp.66-82). New York: Routledge.

Chandra, A., McNamara, K. E., Clissold, R., Tabe, T., & Westoby, R. (2023). Climate-induced non-economic loss and damage: Understanding policy responses, challenges, and future directions in Pacific Small Island developing states. Climate, 11, 74–99.

doi:10.3390/cli11030074

David, E. J. R., & Okazaki, S. (2006). The colonial mentality scale (CMS) for Filipino Americans: Scale construction and psychological implications. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(2), 241–252.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.241

David, E. J. R., & Nadal, K. L. (2013). The colonial context of Filipino American immigrants’ psychological experiences. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(3), 298-309.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032903

Dreher, T., & Voyer, M. (2015) Climate refugees or migrants? Contesting media frames on climate justice in the Pacific. Environmental Communication, 9(1), 58-76.

Farbotko, C. (2019) Climate change displacement: Towards ontological security. In C. Koeck& M. Fink (Eds.) Dealing with climate change on small islands: Towards effective and sustainable adaptation? (pp. 251-266). Goettingen: Goettingen University Press.

Farbotko, C., & McMichael, C. (2019) Voluntary immobility and existential security in a changing climate in the Pacific. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 60(2), 148-162.

Farrelly, T., & Nabobo-Baba, U. (2014) Talanoa as empathic apprenticeship. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 55(3), 319- 330.

Frain, S. C. (2020). Oceania resistance: Digital autoethnography in the Marianas Archipelago in wayfinding and critical autoethnography. In I. Fetaui, S. H. Jones, & A. Harris (Eds.), Wayfinding and Critical Autoethnography. Taylor & Francis Group.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429325410-12/oceania-resistance-sylvia-frain

Frain, S. C. (2023) Famalåo’an in film–Women in film across islands. Okinawan Journal of Island Studies, University of the Ryukyus, 4(2), 144-155.

Kempf, W., & Hermann, E. (2014). Epilogue: Uncertain futures of belonging: Consequences of climate change and sea-level rise in Oceania. In E. Hermann, T. van Meijl, & W. Kempf (Eds.) Belonging in Oceania: Movement, place-making and multiple identifications (pp. 189-213). Oxford: Berghahn.

Kitara, T. & Farbotko, C. (2023, November 13). This is not climate justice: The Australia-Tuvalu Falepili Union.

Toda Peace Institute, Global Outlook Series.

https://toda.org/global-outlook/2023/this-is-not-climate-justice-the-australia-tuvalu-falepili-union.html

Kite, M. E., Whitley, Jr., B. E., & Wagner, L. S. (2022). Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination (4th ed.). Routledge.

Manuela, S., & Anae, M. (2017). Pacific youth, acculturation and identity: The relationship between ethnic identity and wellbeing. Pacific Dynamics: Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 1(1), 129-147.

Manuela, S., & Sibley, C. G. (2015) The Pacific identity and wellbeing scale-revised (PIWBS-R). Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 146-155.

McNamara, K. E., Westoby, R., Clissold, R., & Chandra, A. (2021) Understanding and responding to climate- driven non-economic loss and damage in the Pacific Islands. Climate Risk Management, 33 (2021) 100336, 1-14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100336

Mimura, N., Nurse, L., McLean, R. F., Agard, J., Briguglio, L. P., Lefale, P., Payet, R., & Sem, G. (2007) Small islands. In M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden & C. E. Hanson (Eds.) Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 687-716). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mycoo, M., Wairiu, M., Campbell, D., Duvat, V., Golbuu, Y., Maharaj, S., Nalau, J., Nunn, P., Pinnegar, J., & Warrick, O. IPCC (2022) Small Islands. In H. O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V.

Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (Eds.), Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 2043-2121). Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009325844.017.

Ministry of Culture and Heritage, Mantū Taonga (2023) Dawn raids platform stories.

https://www.mch.govt.nz/our-work/heritage-sector/dawn-raids-platform-stories

Nunn, P. D. (2013) The end of the Pacific? Effects of sea level rise on Pacific Island livelihoods. Singapore Journal of Topical Geography, 34(2), 143-171.

https://doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12021

Nurse, L. A., McLean, R. F., Agard, J., Briguglio, L. P., Duvat-Magnan, V., Pelesikoti, N., Tompkins, E., et al. IPCC (2014). Small islands. In V. R. Barros, C. B. Field, D. J. Dokken, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, & T. E. Bilir,

M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastandrea, L. L. White (Eds.) Climate change 2014. Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 1613-1654). Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-PartB_FINAL.pdf.

Ravuvu, A. (1983). Vaka i taukei. The Fijian way of life. Suva: University of the South Pacific.

Sopoaga, E. (2023, November 27). Australia-Tuvalu falepili union ‘shameful’—former Tuvalu PM. RNZ Pacific News.

https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/503354/australia-tuvalu-falepili-union-shameful-former-tuvalu-pm

Tabe, T. (2022, September 22). Tracking Pacific Islands diasporas.

https://www.eastwestcenter.org/news/east-west-wire/tracking-pacific-islands-diaspora

Teaiwa, K. (2015). Consuming ocean island: Stories of people and phosphate from Banaba. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Vaioleti, T. M. (2006). Talanoa research methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato Journal of Education,12(1), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Westoby, R., Clissold, R., McNamara, K. E., Latai-Niusulu, A., & Chandra, A. (2022) Cascading loss and loss risk multipliers amid a changing climate in the Pacific Islands. Ambio, 51, 1239-1246.

https://doi.org/10.1007? s13280-021-01640-9.

Yates, O., Groot, S., Manuela, S., & Neef, A. (2023) “There’s so much more to that sinking island!”: Restorying migration from Tuvalu and Kiribati to Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Community Psychology, 51, 924-944. DOI: 10.1002/jcop.22928

NOTES

[1] The concept of NELD also features in climate justice discourse, where climate-change induced cultural loss and identity can be viewed as a human rights violation. Treatment of NELD in small island developing states as a form of loss and damage is often omitted from national adaptation planning. At the COP27 UN climate conference in Egypt, decisions were made to establish a Loss and Damage Fund to address the adverse impacts of climate change particularly on developing countries. Although the importance of NELD is recognised in its inclusion in the Paris Agreement and Warsaw Interntional Mechanism, evaluation of these intangible damages needs to be highly tailored to local contexts, and thus they are difficult to rectify (The London School of Economics and Political Science, 2023)

[2] Conversations with Manuila Tausi, Tuvaluan diaspora community leader and Rakoan Tumoa, Kiribati diaspora community leader in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, 4 September 2022.

[3] Breakdown by age group: Born to early Pacific migrants n=5; Migrated during early childhood <6 n=12; Migrated during childhood 6- 17 years old n=9; Migrated as young adult age 18+ n=4.

[4] The Dawn Raids in New Zealand during the 1970s were a controversial period marked by government-sanctioned operations targeting Pacific communities under the pretext of clamping down on immigration violations. These operations involved police and immigration officials conducting early morning raids on the homes of Pacific Islanders, leading to widespread fear, trauma, and racial profiling. The period reflected intense racial discrimination, as Pacific Islanders were disproportionately targeted despite not being the majority of overstayers. The impact of these raids has been long-lasting, affecting the relationship between Pacific communities and New Zealand authorities, contributing to ongoing issues of racial bias and mistrust. (Anae, 2020; Ministry of Culture and Heritage, New Zealand Manatū Taonga 2023)

[5] The diversity and numbers of Pacific Islanders who have immigrated to New Zealand are significant. The 2018 Census data showed a large portion of Pacific immigrants are predominantly from Samoa and Fiji. The largest diaspora communities of Pacific Islanders in New Zealand reside in Auckland drawn by employment opportunities. Other Pacific nations that have contributed to immigration to New Zealand are Tonga, Tuvalu and Kiribati; although Tuvalu and i-Kiribati migrants are smaller in numbers. According to the 2018 Census data, among the roughly 380,000 Pacific peoples in New Zealand, there were 3225 I-Kiribati and 4653 Tuvaluans (Stats New Zealand, 2018).

The Author

DR RIA SHIBATA

Dr Ria Shibata earned her Ph.D. in Peace and Conflict studies from the University of Otago, New Zealand. Presently, she serves as a Senior Research Fellow at the New Zealand Centre for Global Studies and the Toda Peace Institute, Japan. She is also a Visiting Scholar at the University of Auckland. Dr. Shibata’s latest research explores the nexus between climate-induced migration and non-economic loss and damage, such as the loss of cultural identity, dignity, indigenous knowledge, social cohesion and sense of belonging. Her study examines the experiences of Pacific migrants when they are detached from their ancestral lands. Her findings underscore the importance of addressing the intangible impacts of the loss of land and identity when considering future plans and policies for climate adaptation and mobility.

DR SYLVIA C. FRAIN

Dr Sylvia C. Frain is an activist academic working for decolonization and demilitarization in the non-self-governing Mariana Islands. She is an inaugural 2024 Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab fellow with the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, with support from The Japan Foundation, Tokyo. Previously, as a photojournalist in the Republic of Timor-Leste, she completed her Master’s thesis at the University of Queensland, Australia in 2012.

Sylvia earned her Ph.D. in Peace and Conflict Studies at The National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies | Te Ao O Rongomaraeroa at the University of Otago | Te Whare Wānanga Otāgo in Ōtepoti | Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand.

IEMAIMA VAAI

Iemaima Vaai recently moved home to Samoa and works for Conservation International Samoa as the Program Communications Associate for the Samoa Ocean Strategy (SOS). She is of Samoan descent, has an academic background in climate change and environmental management, and specializes in loss and damage. She has extensive ground research experience in climate-induced displacement and relocation in the Pacific and its relation to loss of culture, identity, and indigenous knowledge.

She is an ecological stewardship and climate justice activist at heart. She has formerly worked and volunteered in and out of the NGO—non-profit space in Fiji, focusing on climate justice, conservation, decolonization, the revival of Indigenous knowledge, community engagement and resilience, and youth empowerment.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org