Global Challenges to Democracy Report No.227

Democratic Resilience in the United States: Containing Trump’s Threat to Democracy?

Robert R. Kaufman

July 04, 2025

This report provides a comparative perspective on two crucial questions. First, what are the possibilities that the United States might devolve into what political scientists have called a ‘competitive authoritarian regime’—one in which the façade of democratic institutions obscures the reality of political power that cannot be held to account by either constitutional checks-and-balances or by the electorate itself? Second, to what extent can its institutions recover from the damage incurred under Trump 2.0? Few, if any, ‘recovering’ backsliders have regained the level of democratic quality they had achieved prior to the backsliding episode. A likely scenario is one in which a post-Trump democracy would emerge significantly weaker than it was before.

Contents

- Introduction

- PART 1: SOCIOECONOMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL SOURCES OF RESILIENCE

- PART TWO: HOW MUCH DAMAGE? WHAT ABOUT RECOVERY?

Introduction

Since regaining the presidency in 2025, Donald Trump and his allies have launched a devastating attack on American democracy. The targets of this attack are the checks and balances, and the civil and political rights that have provided the foundations of our constitutional system for over two centuries. In the few short months of Trump’s second term, it is still too soon to say how Trump’s onslaught will end. But it is already clear that the threat he currently poses to democracy in the United States is far more severe than they were in his first term.

During his first term (2017–2021), Trump succeeded in eroding deeply held norms of political discourse and practice, but U.S. political and constitutional institutions remained more or less intact. Challenges to the democratic system—including on January 6—were contained by congressional opposition, by the courts, by the press, and by civil society—as well as by opponents within the Republican party itself. During the second term, constitutional institutions have come under a much more devastating attack by a far more unified presidential elite. With the acquiescence of Republican congressional majorities, the Trump administration has unilaterally undertaken massive purges of the federal bureaucracy, sought to weaken or eliminate independent agencies, violated the civil rights of immigrants, and deployed regulatory and fiscal powers in an attempt to bring both universities and corporations under his control. Lower courts have moved to block some of these initiatives, but it remains to be seen whether their rulings will be backed by the highly conservative Supreme Court, or even whether Trump will abide by them if they are.

In this paper, I provide a comparative perspective on two crucial questions raised by these developments. First, what are the possibilities that the United States might devolve into what political scientists have called a ‘competitive authoritarian regime’—one in which the façade of democratic institutions obscures the reality of political power that cannot be held to account by either constitutional checks-and-balances or by the electorate itself? There are, as I will argue below, important impediments to this development, but given the severe backsliding that we have already witnessed under Trump 2.0, it is a possibility that should be taken very seriously (Levitsky and Way 2025).

The second issue—assuming that American democracy does survive in some form—is the extent to which its institutions can recover from the damage incurred under Trump 2.0. The prospects in this scenario are very far from encouraging. From a comparative perspective, we find that few, if any, ‘recovering’ backsliders have regained the level of democratic quality they had achieved prior to the backsliding episode. And in the United States itself, democratic institutions did not return to a prior equilibrium following the defeat of Trump 1.0. Although I speculate on the possibility of a political realignment that places American democratic institutions on a more secure footing, the more likely scenario is one in which a post-Trump democracy would emerge significantly weaker than it was before.

I address these questions in two steps. The first section examines the current challenges to democracy in the United States in the context of socioeconomic and institutional sources of resilience widely discussed in the comparative literature. In the second, I review the experience of “recovering” backsliders to speculate on possible post-Trump scenarios.

My thanks to Heidi Burgess, other colleagues in the Toda research group, and to Stephan Haggard for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

PART 1: SOCIOECONOMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL SOURCES OF RESILIENCE

SOCIOECONOMIC SOURCES OF RESILIENCY

We begin with a consideration of the effects of extensively studied socioeconomic sources of democratic resilience. As we have already indicated above, it is important to emphasize the distinction between backsliding (the incremental erosion of democratic institutions) and reversion to a competitive authoritarian regime in which minimum standards of democracy are no longer maintained. Following Przeworski and Limongi (1997), Rustow (1970), Linz (1978), and others, those minimum standards would include broad suffrage and relatively free elections in which oppositions will have a reasonable chance of replacing the incumbent government. It is also a standard that appears to motivate the widely-used V-Dem classification of electoral democracy.[1]

Experience in the United States itself leaves no room for doubt that wealthy democracies are far from invulnerable to backsliding; see, for example, Reidel et al. (2025). On the other hand, the robust empirical relation between economic development and the survival of democracy has been a bedrock feature of the political science literature since Lipset’s (1959) seminal article on that issue was published over sixty years ago. Przeworksi et al. (1997) went farther, famously showing that no democracy had failed in societies with a per capita GDP above $6055 in 1975 dollars, the level that Argentina had reached prior to the 1976 coup d’etat. And these claims have received more recent affirmations in studies by Brownlee and Maio (2022) and Danield Treisman (2023), who conclude that the rate of breakdown is extremely low for countries (like the US) with high levels of GDP and long histories of democracy.[2]

The United States is by far the wealthiest country to face a serious threat of democratic breakdown, with a per capita GDP of $89,678—well above the inflation-adjusted Przeworski threshold ($35,966 in 2025) —and the eighth highest in the world. South Korea—which has so-far successfully fended off major threats—is the only other backsliding country to exceed this threshold, with a per capita GDP of $37,675. Hungary—the wealthiest backsliding country to succumb to authoritarianism—had a GDP of only $25,703 in 2024. Although there is abundant reason to be concerned about the health of American democracy, therefore, its high level of economic development provides a reason to be hopeful about its survival.

It should be emphasized that the causal (as distinguished from the empirical) links between development and democracy remain unclear, and they cannot necessarily be expected to remain robust going forward. The United States is a wealthy society, but it is also a very unequal one, and that is the source of considerable political conflict.[3] Reidel et al. (2025), moreover, observe that the combination of capitalism and generous social protections that provided the foundations for post-World War II democracies has been severely eroded by the dislocations of globalization, growing inequality, and identity conflicts. The erosion of this democratic ‘class compromise’ is especially pronounced in the United States, where the provision of social welfare protections was already more limited than those in other developed democracies.

Notwithstanding these caveats, however, it remains likely that the high level of economic development will remain a major—if far from a fool-proof—source of resilience in the United States. Important works by Carles Boix (2003) and by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (2006) have posited a connection between high inequality and democratic breakdown, but the empirical evidence for their claims is mixed, at best; redistributive conflicts between elites and masses accounted for only a relatively limited number of breakdowns among ‘third wave’ democracies (Haggard and Kaufman 2012, 2016).

Wealthy societies, moreover, have other attributes that provide some protection from the threat of breakdown, even at relatively high levels of inequality. These include higher levels of literacy, larger middle classes, more diverse private sectors, bigger cities, and more secular and tolerant cultures.[4] All are strongly associated with democratic survival (see Ingelhart and Welzel 2010; Inglehart 2016; Levitsky and Way 2023). More generally, Przeworski and Limongi (1997) and Boix and Stokes (2003) theorize that, in rich societies, it is more rational for power contenders to struggle to expand their share of the wealth within a democratic system than to incur the high costs of trying to gain it all through an authoritarian seizure of power. If a high level of wealth does not guarantee the survival of democracy in the United States, it does vastly increase the odds that the system will continue to be characterized by at least the minimum standards of accountability to a broad electorate.

CIVIL SOCIETY, INSTITUTIONAL, AND ELECTORAL SOURCES OF RESILIENCE

In general, despite severe polarization that has roiled the US political system, the prospects for the survival of democracy in the United States are also bolstered by the characteristics of civil society and its political institutions—a major focus of attention in recent studies of resilience (Merkel 2023; Croissant and Lott 2024). We turn first to the strengths and weaknesses of American civil society and then to an assessment of the institutional and electoral checks that can help to impede the centralization of power.

Civil Society

Potentially, opposition from civil society and the mass public remains a major impediment to a long-term consolidation of power. United States scores .98 in the civil society index based on V-Dem data. These scores are based on estimates of the extent to which major civil society organizations are “routinely consulted by policymakers, how many people are involved in them, women can participate, and candidate nomination for the legislature within parties is decentralized or made through primaries.” The U.S. score was far higher than those of other backsliders, such as Hungary 0.44; India 0.59; Poland 0.71; and Korea 0.81.

Civil society, to be sure, was caught off-guard by the ‘flood the zone’ approach adopted during Trump’s first months (see Kaufman 2025). During the early months of Trump’s second term, civil society organizations, the press, and big business—all important checks during the first Trump term—have appeared dazed, confused, and intimidated. Many corporate leaders and major universities have sought to cut separate bargains with the administration in order to gain favourable treatment and/or minimize losses.

As societies become more polarized, moreover, civil society organizations can be mobilized in support of, as well as opposition to, autocratizing governments. In the United States, the movements supporting Trump’s rise to power have been increasingly populated by a powerful network of think tanks, internet activists, business organizations, and religious groups. As Reidel et al. (2025) note, civil society [as well as horizontal institutions] can be a crucial site of democratic contestation, but it can also be “repurposed to serve autocratic ends.”

But our vision should not be restricted to the onslaught of early 2025. Over time, opponents in civil society are also likely to regain their voices. To some extent, this is already happening. Thousands of civil society organizations, networks and coalitions working at the state and local level are already engaging in efforts to promote free speech, fight disinformation, de-escalate community conflicts, improve civic education, and promote electoral reform.[5] Trump’s extremist tariff and immigration policies have provoked strong protests from trade associations and civil rights organizations. Law schools and legal professional associations have bolstered judicial efforts to push back against abuses of authority. And Harvard’s decision to oppose threats to academic freedom has provided a focal point for collective resistance from many other universities. As Trump’s initial ‘honeymoon’ fades, we can expect more active opposition from human rights organizations, business associations, and others.

Political Institutions: Congress, Courts, Federalism

To succeed in his attempt to concentrate personal power, Trump must also find ways to overcome the many ‘horizontal’ constraints built into the United States constitution. As already suggested, this is not necessarily an impossible task, given the extensive political and social polarization that now afflicts American society. The profoundly polarized two-party system is the weakest link in the democratic system, and the current Republican control of Congress constitutes a significant change from the first Trump administration.[6] In the first two years of that term (2017-2018), Trump confronted significant divisions within the Republican majority itself, including support from influential Republican leaders for the authorization of the Mueller investigation. Between 2019 and 2021, the Democrats’ recaptured the House of Representatives and imposed even greater constraints on Trump’s presidency—including, of course, impeachments and widely-viewed public hearings. But Trump 2.0 has been far less constrained by the need to manage disparate governing coalitions in the legislature.[7] Since 2025, small, but now far more disciplined, Republican majorities have regained control of both houses of Congress and have acquiesced to a radical extension of presidential power—deep into the federal civil service, into law enforcement and the courts, and even into some state and local governments.

Even taking these threats into account, however, the US constitutional system contains multiple veto points that can impede the complete dismantling of democratic institutions. We focus specifically on the role of the courts, the US federal system—and, potentially, a revived Congress— as impediments to the full collapse of democracy.

The courts. Turning first to the role of the judiciary, it is important to note that comparative evidence on the role of judicial systems is rather mixed: Boese et al. (2020) find that independent courts do impose a significant constraint on backsliding governments. Croissant and Lott (2024), on the other hand, find that, although judicial independence deters the onset of backsliding, that effect disappears once backsliding is underway. Haggard and Tiede (2024), like Boese et al. (2020), view the judiciary as a potential check on executive aggrandizement, but they warn that the weakening of legislative oversight is associated with greater backsliding risk.

This warning, of course, is especially relevant to the United States. Historically, US courts have long been cautious about challenging decisions made by the political branches. And with the consolidation of a conservative Supreme Court majority during Trump’s first term, the Court has tilted sharply to the right—favouring an expansion of presidential authority over independent regulatory agencies and granting the president broad immunity from criminal prosecution.[8]

At least until very recently, however, the judiciary has also imposed important constraints on presidential authority. District and appellate courts have ruled against the administration on issues related to immigration, academic freedom, and civil rights. Their authority to do so, it should be noted, was weakened substantially by a Supreme Court ruling in June 2025 that barred federal district courts from issuing nation-wide injunctions that protected individuals who had not been parties to the suits; this had been a powerful tool previously used to check the executive branch. But the full scope of this ruling remains to be litigated, and in the meantime, there are other avenues (such as class-action suits) through which citizens can seek redress through the lower courts. Moreover, even with a 6-3 majority on the Supreme Court, the Trump administration is unlikely to escape completely from impediments to their attempts to evade constitutional limits.

Institutionally, the right of judicial review provides courts with considerable constitutional leverage (Haggard and Tiede 2024). Conflicts with the judiciary, as noted, are still ongoing, and as with the case of Kilmar Obrego Garcia, some adverse rulings might simply be ignored. But strengths of the judiciary are deeply rooted. These rest not only on legal precedents of judicial authority going back to the founding of the Republic, but also on the fact that the court system has long-standing roots in civil society. Although right-wing organizations such as the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation have come to exercise considerable power over the selection of judges, the path to appointment continues to go through established schools of law, clerkships, and influential bar associations. The norms of behaviour acquired during that process are sometimes violated, but they continue to serve as checks on politically-motivated decisions. The result has been that even “Republican” judges—including those appointed by Trump himself—have pushed back against Trump’s attempts at executive aggrandizement.[9]

The federal system. The highly decentralized federal system in the United States also serves as an important constraint on the centralization of political power. Compared to many other federal systems around the world, states and local governments maintain substantial control over law enforcement, budgets, social policy, and the electoral system itself (see Kaufman, Kelemen, and Kolcak 2024). This independence, to be sure, does not always prove beneficial to American democracy. Historically, state-level enclaves of authoritarianism have been deployed to violate the civil and political rights of Black minorities and Native Americans (Gibson 2012). In the contemporary era of political polarization, moreover, the expansion of Republican control in ‘red states’ has contributed to the erosion of federal constraints on Trump’s power (Grumbach 2022).

But robust state and local powers have always been a double-edged sword (Bednar 2009). As my co-authors and I have argued elsewhere (Kaufman, Kelemen, and Kolcak 2024), the same state strength that can diminish democracy can also protect it from autocratic assaults at the national level. Critically, the decentralized administration of elections helped to prevent Trump’s attempt to subvert the 2020 presidential election. Democratic and even some Republican office-holders blocked schemes to rig elections in key battleground states. Their efforts to protect election results were upheld, moreover, by state courts as well as by federal judges, including those with known Republican affiliations.

Struggles over state and local control, of course, have continued and even intensified since the 2024 election. Conflicts over federal authority escalated substantially in June 2025, when Trump sent Marines and National Guard to Los Angeles to put down protests over immigration round-ups—over the objections of Governor Gavin Newsom and Mayor Karen Bass. Notwithstanding this disturbing turn of events, however, state governments, legislatures, and courts remain major platforms for the mobilization of political opposition and for the projection of its influence at the national level.

Congress and the political parties? Both the continuing independence of the courts and the leverage available to the opposition within the federal system provide important opportunities for the revival of Congress as a bulwark against authoritarianism. As long as these doors remain open to pressures from civil society and the electorate, both incentives and political alignments can be expected to change in a favorable direction. Historically, the opposition party typically gains House seats in midterm elections; and with the Republicans currently holding only a narrow majority, the Democrats stand a good chance of regaining control of that chamber. In fact, given the current erosion of Trump’s popular support, they might do so by a large margin. And although the Senate and the President himself might block their legislative initiatives, House Democrats can hold hearings, dominate the news cycle, obstruct Trump’s agenda, and advance popular proposals of their own.

Moreover, some Republicans, who are now acting in lock step with the Trump administration, are likely to display greater independence as a result of presidential decisions that affect their electoral chances. As I have argued elsewhere, serious cleavages—already evident to some extent—can be expected to widen between internationalists and isolationists, and between MAGA hardliners and more traditional ‘free-market’ leaders (Kaufman 2025). Of course, many things can go wrong, and democracy may well emerge seriously diminished; but it is reasonable to expect that the momentum behind Trump’s bid for autocratic control will encounter substantial congressional headwinds.

Vertical Accountability: The Electorate

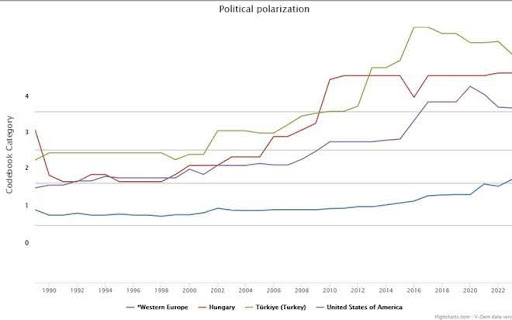

Perhaps the most serious danger to American democracy is posed by the deep division within the mass public—a division that so far has provided Trump and the far right with a bedrock minimum of electoral support. The level of polarization in the United States far exceeds that of Western Europe and is comparable to those of other backsliders that have lapsed into authoritarian rule (see Figure 1). Even if American democracy survives, continuing polarization will be a major source of instability.

However, polarization also implies significant mass opposition to—as well as support for —the Trump movement. Trump has never won over 50 percent of the voters: he won only 46 percent in 2016 and 49.8 percent in 2024. Moreover, as briefly noted above, public support has dropped steadily since he returned to the presidency, with approval ratings currently in the low 40s. Presidential approval ratings were hit especially hard since the unveiling of Trump’s radical tariff initiatives, and they are likely to decrease even more as the consequences of these measures unfold.

To be sure, we cannot expect Trump’s electoral support to collapse entirely. The MAGA base (about 30 percent of the electorate) is very likely to remain loyal; and in the current media environment, many other Trump voters might be confused about who is accountable for the difficulties they are experiencing. Even so, we can expect further defections as conditions worsen. This is highly likely to provide some wind at the back of the Democratic opposition and to weaken the loyalty of some Republican political leaders.

Figure 1: Political Polarization: Hungary, Turkey, United States, Western Europe

CONCLUSION: PART I

The second Trump presidency is far more dangerous than the first. Society is even more polarized than before, horizontal checks are weaker, and purges of the civil service, together with the appointment of loyalists, have eliminated or weakened internal checks within the federal bureaucracy. Yet the impediments to the consolidation of autocratic power are also significant. Far more than in backsliding democracies elsewhere, an authoritarian project in the United States is constrained by a wealthy, diversified, and complex economy, as well as by a robust civil society and a broad swath of public opposition. Institutional constraints also remain a continuing source of resilience. These include the checks provided by the United States judiciary, its federal system, and increasingly likely, its Congress.

As we will discuss below, these sources of resilience are unlikely to prevent further deterioration of American democracy. At the end of the next four years, it is realistic to expect the political system to be characterized by far weaker legal restrictions on the arbitrary exercise of power, weakened constitutional checks, and continuing abuses of civil liberties. Indeed, several leading theorists have argued that the ‘costs of opposition’ have risen so high under the second Trump presidency that the United States has already become a competitive authoritarian regime (Levitsky, Way, and Ziblatt (2024).

But in their seminal work on competitive authoritarianism (2012), Levitsky and Way also argued that the conceptual boundary between flawed democracies and competitive authoritarian regimes, though faint, is nevertheless significant: it marks the difference between a “playing field” in which oppositions have a reasonable chance to constrain incumbent governments and win elections, and ones in which such chances are vanishingly small. This bare-bones distinction strips away or de-emphasizes many of the “horizontal” accountability mechanisms associated with liberal democracy. But it is one that is far from trivial, and it is consistent with a broader theoretical tradition that insists that democracy should be conceived in dichotomous terms—either a regime is democratic or it is not (Linz 1978; Przeworski et al. 1997; Rostow 1970).[10]

In the United States, opponents to Trump’s attacks on democracy have faced harassment, intimidation, and—in some cases—violence or imprisonment. Even so, I have tried to show that the American ‘playing field’ remains open to meaningful political competition in civil society, the courts, and at the state and local level. The 2026 congressional elections will pose the next big test of the democratic system, and we can expect increasing challenges to voter rights and ballot counts. But the opposition can also wield institutional and political resources to defend legitimate electoral outcomes, and a Democratic victory in 2026 would significantly alter the political equation. From this perspective, it is reasonable to conclude that American democracy is still alive, if only barely, and that it has a significant chance of remaining so. In the next section, we take up the question of what a post-Trump democracy might look like.

PART TWO: HOW MUCH DAMAGE? WHAT ABOUT RECOVERY?

Speculation about the course of American democracy over the next four years must be tempered by the fact that the system is sure to be impacted by exogenous shocks that cannot be anticipated in advance. In this connection, it is important to recall that Covid played this role during the first Trump term, and is likely to have contributed materially to his defeat in the 2020 election. This time around, such shocks might well come from the reckless behavior of Trump himself on both the domestic front and the world stage. He might well be vulnerable to his own policy mistakes with respect to trade, tax and spending policies, or international conflicts. One way or another, we can be fairly certain that shocks will come, even though their timing and effects are impossible to predict. Despite this uncertainty, however, it might be useful to attempt to peer through the fog and speculate on alternative scenarios that might lie ahead. In this section, I elaborate on my previous concerns about the prospects for a full recovery, but also briefly posit the possibility of a more hopeful future.

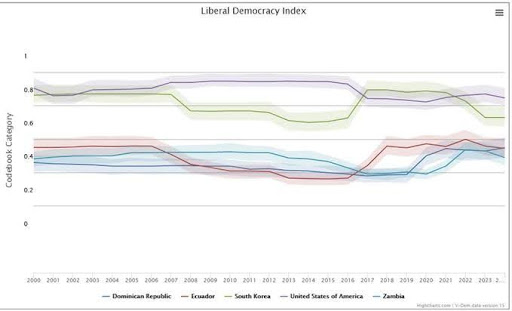

As noted in the introduction to this paper, the comparative evidence that democracy can fully recover from backsliding episodes is far from encouraging. In eleven of the sixteen backsliding cases examined by Haggard and Kaufman (2021) democratic oppositions succeeded in ousting autocratic rulers and in restoring constitutional governments. But eight of these—including Joseph Biden’s administration—failed to rebound to the level of Liberal Democracy scores achieved prior to the backsliding episodes (see Figure 2).[11] Post-backsliding democracies in Ecuador, Zambia, and the Dominican Republic did return to pre-backsliding levels (Figure 2); but the previous democratic regimes had been characterized by weak states, corruption and political fragmentation; and in the aftermath the episodes, their democracies returned mainly to this status quo ante, remaining vulnerable to corruption and political stalemate. (on Ecuador, for example, see Polga-Hecimovich and Sanchez (2021).

Figure 2: Liberal Democracy: Dominican Republic, Ecuador, South Korea, US, Zambia.

The challenges to full recovery are also evident in South Korea, a country not included in the Haggard and Kaufman study (but also shown in Figure 2).[12] In 2017, a backsliding episode was halted when President Park Geun-hye—the daughter and political heir of a former military ruler, Park Chung-hee—was impeached and convicted on charges of corruption and abuse of power (Laebens and Lurhmann 2021). Unlike the ‘recovering democracies’ discussed above, South Korea had previously been classified as a ‘liberal’ democracy, and like the United States, its economy exceeded the ‘Przeworski threshold’ of rich countries immune to democratic collapse. Predictably, Park’s ouster was driven by strong civil society protest, followed by robust responses from the country’s parliament and judiciary (Laebens and Luhrmann 2021).

But Korea’s society remained highly polarized, and the return to democratic ‘normalcy’ remained relatively short-lived (see Figure 2). In 2022, Park’s conservative party, the People’s Power Party (PPP), regained the presidency under the leadership of Yoon Suk-yeol. In 2024, Yoon declared martial law and summoned troops to close parliament in a brief, but shocking, attempt to seize autocratic power. Once again, democracy held. Civil society and parliamentary resistance led to the defeat of the coup in a matter of hours, and Yoon was forced from power. But the crisis had a profoundly unsettling effect on the political system—as reflected in a decline in the country’s Liberal Democracy index from a high of 0.80 after the ouster of Yoon to only 0.61 in 2024.

Can American democratic institutions be strengthened in the aftermath of the second Trump administration, or will they replicate the weaknesses that led to his return in 2025? Any discussion about a democratic recovery must begin by taking into account the enormous damage that has already been done to American society and to its position in the world. Trump’s attack on long-standing geopolitical alliances has severely damaged American credibility as an anchor of international law and provider of ‘soft power’ promotion of international security and well-being. In just the first few months of 2025, he has undermined Biden’s effort to bring the country back from the international damage of his first term. The challenge will be even greater for any government seeking to resume leadership in the aftermath of the second term.

On the economic front, the reckless tariff and trade policies pursued in the quixotic attempt to “bring back manufacturing” have drastically—and quite possibly, irreversibly—altered supply chains and investment options. Uncertainty with regard to regulatory and fiscal policy is also likely to place a significant drag on investment and prices, and there has already been a significant shift away from American equities and debt. In the longer term, such factors are likely to lead to a severe weakening of the United States’ role in the global economy—almost certainly to the advantage of China.

Finally—and perhaps most importantly—the attacks on the federal bureaucracy through mass firings and job uncertainty have severely weakened the state’s capacity to deliver critical services, health and education, and public safety. The lost institutional memory and expertise that go into the provision of such public goods will be difficult, if not impossible, to replace in the coming years. These crippling deficits in state capacity will leave Trump’s successors with only a limited ability to respond effectively to popular expectations and demands.

It should already be clear that I find little reason for optimism that these challenges can be decisively overcome. Given the profound uncertainties we face, however, it is useful to speculate on a more positive outcome. It is conceivable, if far less likely, that the radical and destructive initiatives of Trump 2.0 could generate an equally radical realignment—one that would produce a large, new majority coalition, marginalize Trumpian extremists, and establish a new foundation for competitive democratic politics and a reconstruction of the American state.

I cannot point to contemporary cross-national examples of such an outcome (but see Bateman’s (2025) discussion of ‘democracy reinforcing’ hardball). However, US history itself does provide examples of major partisan realignments (1896 and 1932) that upended the prior balance of political power and produced profound changes in the country’s political economy. One—launched under McKinley in the 1896 election—led to long-term dominance of the Republicans in the Northeast and Western states. The New Deal launched by Roosevelt after 1932 rested on a new coalition of Northeast labour, Mid-West progressives, and southern Democrats. Both the McKinley and Roosevelt realignments, it should be emphasized, were engineered at the cost of unpardonable deals with Southern white elites that denied the civil and political rights of African Americans. However, under the Republican dominance of the early 20th century, the United States emerged as an industrial economy and as a major world power. And the New Deal coalition laid the foundations for the establishment of America’s modern welfare state—and, eventually, for responses to demands for social justice for Blacks and other excluded minorities.

A major realignment in the 21st century would look very different from either of these historical examples. Most assuredly, an attempt to resurrect the industrial and union-based foundations of the past would founder in the face of revolutionary changes in production and communications technology, global integration, and artificial intelligence. A new coalition would require a project that combined the social and political interests that have emerged out of these changes with effective strategies to respond to the massive insecurities and inequalities that these changes have produced.[13]

If such a coalition is possible at all, however, it would most likely emerge—as was the case under Roosevelt—through trial-and-error responses to unexpected events, rather than through a clearly planned-out, ‘top-down’ strategy, which would surely have negative side-effects that would be difficult to reverse. More important, attempts to construct such a coalition, whether from the ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up’ would carry very high—and quite possibly unacceptable—political and constitutional risks. Ironically, the institutional checks and balances that might work to impede the centralization of power under Trump would also be likely to frustrate radical reforms pursued by a new governing coalition. Overcoming such obstacles, in turn, might well require the ‘democracy-reinforcing’ hardball strategies discussed by David Bateman (2025) that test the outer-limits of the norms and institutions of democratic politics.[14] And this, in turn, is unlikely to succeed in the absence of devasting crises that reduce Trump’s support to its hardcore minority.

For those concerned with finding enduring ways to confront the current threat to US democracy, these observations pose a major dilemma. Bold—'hardball’ opposition—might well optimize the long-run chances of re-founding the American political system. But in the short-run, it risks a radical reaction and a disastrous defeat. In the immediate future, on the other hand, the best way to slow or block Trump’s autocratic agenda might be through more moderate appeals that reaffirm—and respect—the importance of constitutional limits. This is clearly a far more prudent course of action. But it might well come at the cost of accepting a far more fragile democracy, one that is doomed to contend with the enduring polarization of American society.

REFERENCES

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Bateman, David Alexander. 2025. “Democracy-Reinforcing Hardball: Can Breaking Democratic Norms Preserve Democratic Values?” Comparative Political Studies (January), 1–35.

Bednar, Jenna. 2009. The Robust Federation: Principles of Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boese, Vanessa A., Amanada B. Edgell, Sebastian Hellmeier, Seraphine F. Maerz, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2020. “Deterring Dictatorship: Explaining Democratic Resilience since 1900,” Working Paper Series 2020–101, The Varieties of Democracy Institute.

Boix, Carles. 2003. Democracy and Redistribution. Cambridge University Press.

Boix, Carles and Susan C. Stokes.2003. “Endogenous Democratization.” World Politics 55:4 (July): 517–49.

Brownlee, Jason and Kenny Miao. 2022. “Why Democracies Survive” Journal of Democracy 33:4 (October):133–49.

Burgess, Heidi and Guy Burgess. 2024. “Massively Parallel Problem Solving and Democracy Building: An Ongoing Response to Threats to Democracy in the U.S.” Toda Peace Institute. Report No 100 (16 September).

Croissant, Aurel and Lars Lott. 2024. “Democratic Resilience in the Twenty-First Century: Search for an Analytical Framework and Explorative Analysis.” Working Paper, Series 2024:149, Varieties of Democracy Institute.

Gibson, Edward L. 2012. Boundary Control: Subnational Authoritarianism in Federal Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139017992.

Grumbach, Jacob M. 2022. Laboratories against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. DOI: 10.1515/9780691218472.

Haggard, Stephan and Robert R. Kaufman. 2012 “Inequality and Regime Change: Democratic Transitions and the Stability of Democratic Rule,” American Political Science Review, 106:3, 495–516.

Haggard, Stephan and Robert R. Kaufman. 2016. Dictators and Democrats: Masses, Elites, and Regime Change. Princeton University Press.

Haggard, Stephan and Robert R. Kaufman. 2021. Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World. Cambridge University Press (United Kingdom, New York, Melbourne, New Delhi, and Singapore).

Haggard, S., & Tiede, L. 2024. Judicial backsliding: a guide to collapsing the separation of powers. Democratization, 32(2), 513–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2024.2381092

Inglehart, Ronald. 2016. “How Much Should We Worry?” Journal of Democracy, 27:3 (July): 18–23.

Inglehart, Ronald and Christian Welzel. 2010. “Changing Mass Priorities: The Link between Modernization and Democracy.” Perspectives on Politics 8:3 (June), 551–67. Kaufman, Robert R. 2025. “Trump’s First Month: Flooding the Zone” Toda Peace Institute (24 February) https://toda.org/global-outlook/2025/trumps-first-month-flooding-the-zone.html.

Kaufman, Robert R.; R. Daniel Kelemen, and Burcu Kolcak. 2024. “Federalism and Democratic Backsliding in Comparative Perspective.” Perspectives on Politics 23:1 (March), 15–34.

Klein, Ezra and Derek Thompson. 2025. Abundance. Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster.

Linz, Juan J. 1978. The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Crisis, Breakdown, and Reequilibration. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Laebens, Melis G. and Anna Luhrmann. 2021., “What Halts Democratic Erosion? The Changing Role of Accountability.” Democratization, 28:5, 908–28.

Levitsky, Steven and Lucan A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press

Levitsky, Steven and Lucan A. Way. 2023. “Democracy’s Surprising Resilience.” Journal of Democracy, 34:4 (October), 5–20.

Levitsky, Steven and Lucan A. Way. 2025. “The Path to American Authoritarianism: What Comes after Democratic Breakdown.” Foreign Affairs (March/April), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/path-american-authoritarianism-trump

Levitsky, Steven, Lucan Way, and Daniel Ziblatt. 2025. “How Will We Know When We Have Lost Our Democracy?” New York Times (May 8).

Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1959. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review, 53:1 (March), 69–105.

Merkel, Wolfgang and Anna Lührmann. 2021. “Resilience of democracies: responses to illiberal and authoritarian challenges.” Democratization, 28:5, 869–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1928081

Merkel, Wolfgang. 2023. “What is Democratic Resilience and How Can We Strengthen It?” Toda Peace Institute. Policy Brief No. 169 (August).

Polga-Hecimovich, John and Francisco Sanchez. 2021. “Ecuador’s Return to the Past”. Journal of Democracy, 32: 3 2021 (July), 3–15.

Przeworski, Adam and Fernando Limongi. 1997. “Modernization: Theories and Facts,” World Politics, 49:2, 155–83.

Przeworski, Adam; Alvarez, Michael E.; Cheibub, José Antonio; and Limongi, Fernando. 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Riedl, Rachel Beatty, Paul Friesen, Jennifer McCoy, and Kenneth Roberts. 2025. “Democratic Backsliding, Resilience, and Resistance,” World Politics, Volume 77, 75th Anniversary.

Rostow, Daniel. 1970. “Transitions to Democracy: Toward a Dynamic Model.” Comparative Politics, 2 (April), 337–63.

Stokes, Susan C. 2025. The Backsliders: How Inequality and Trash-Talking Leaders Undermine Democracy. Princeton University Press.

Treisman, Daniel. 2023. “How Great is the Current Danger to Democracy? Assessing the Risk with Historical Data,” Comparative Political Studies 56:2, 1924–52.

Weyland, Kurt. 2024. Democracy’s Resilience to Populism’s Threat: Countering Global Alarmism. Cambridge University Press. (United Kingdom, New York, Melbourne, New Delhi, and Singapore).

Notes

[1]V-Dem definition is that: electoral competition for the electorate's approval under circumstances when suffrage is extensive; political and civil society organizations can operate freely; elections are clean and not marred by fraud or systematic irregularities; and elections affect the composition of the chief executive of the country. In between elections, there is freedom of expression and an independent media capable of presenting alternative views on matters of political relevance.

[2]Levitsky and Way (2023) suggest in a recent Journal of Democracy article that democratic collapse is relatively unlikely even in countries that have reached middle levels of development.

[3]Stokes (2025) claims that there is a very high correlation between inequality and backsliding.

[4]As is customary, this generalization does not apply to societies in which high wealth derives predominantly from petroleum.

[5]For a very useful summary of these activities, see Burgess and Burgess (2024).

[6]Croissant and Lott (2024) argue that party systems provide the weakest components of democratic resilience across democracies in Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia.

[7]But see alternative view by Kurt Weyland (2024).

[8]The Court’s controversial decision in 2024 on presidential immunity for “official” acts has also opened the way to blatant and extensive acts of corruption on the part of the president and members of his family – most recently, the acceptance of Qatar’s $400 million gift of a presidential airplane.

[9]See, for example, Linda Greenhouse (2025) “Should Reporters Identify Judges by the President Who Nominated Them?” Guest Essay. New York Times, May 12, 2025.

[10]Regimes of the World (ROW) – a widely used categorical ranking of regime types – provides a comparative perspective. In 2024, before Trump’s second term, RoW continued to classify the United States as a “liberal democracy,” despite the damage done in the first Trump term. We can expect the ranking to be considerably lower in the 2025 edition, which will take the second term into account.But to fall entirely out of the RoW “democracy” category altogether, the United States would need to be placed below Zambia, North Macedonia, and Nigeria, each of which were rated as ED- [“Electoral Democracies minus] despite far more fragile social and political institutions. Even a higher ED standard would place it on a level of countries such as Slovakia, Solomon Island, Sri Lanka, Suriname, and Timor-Leste. (p. 14V-Dem Institute, “Democracy Report 2025: 25 Years of Autocratization – Democracy Trumped?” It remains unlikely that, despite the deterioration, the United States would fall below this threshold.

[11]The others did not. These included (Brazil, Poland, North Macedonia, Greece, Ukraine, Bolivia, Serbia, and the United States following Trump’s loss of the presidency in 2020).

[12]Melis G. Laebens and Anna Luhrmann (2021), “What Halts Democratic Erosion? The Changing Role of Accountability,” Democratization 28:5, 908–28.

[13]For example, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson (2025).

[14]David A. Bateman, “Democracy-Reinforcing Hardball: Can Breaking Democratic Norms Preserve Democratic Values?” Comparative Political Studies 2025, 1–35 Special issue edited by Giovanni Capoccia and Isabela Mares. As historical examples, Bateman points to the Reconstruction period in the United States, the formation of the French Fifth Republic under Charles DeGaulle, and the passage of the British Parliament Act in 1911, which eliminated the veto power of the House of Lords.

The Author

ROBERT R. KAUFMAN

Robert R. Kaufman is Distinguished Professor Emeritus in Political Science. His most recent books are Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World (Cambridge University Press 2021) and Dictators and Democrats: Elites, Masses, and Regime Change (Princeton University Press 2016), co-winner of the Best Book Prize awarded by the Comparative Democratization Section of the American Political Science Association.

Other books include Development, Democracy, and Welfare States: Latin America, East Asia, and Eastern Europe (2008), coauthored with Stephan Haggard. He is also co-author of The Political Economy of Democratic Transitions (with Stephan Haggard), winner of the 1995 Luebbert Prize for the best book in comparative politics, awarded by the Comparative Politics Section of the American Political Science Association. He is co-editor (with Joan M. Nelson) of Crucial Needs, Weak Incentives: Social Sector Reform, Globalization and Democratization in Latin America (2004).

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org