Peace and Security in Northeast Asia Policy Brief No.224

Toward A ‘Reassurance Spiral’ in US-China Relations

Carla Freeman

June 09, 2025

This policy brief examines how the United States and China could initiate a ‘reassurance spiral’ to reduce escalating tensions and mitigate the risk of military conflict. Bilateral relations are deteriorating amid growing strategic and economic competition, mutual insecurity, and reduced cooperation channels and the risks of frictions igniting conflict are on the rise. Both nations face an urgent need for reassurance strategies that credibly demonstrate benign intentions without compromising deterrence capabilities. This brief argues that reassurance is possible, despite significant challenges. There are initial steps that are ‘low cost’ that could enable the two countries to reassure each other to create reciprocal positive momentum that could evolve into reduced bilateral tensions.

Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Background

- Cold War lessons

- Launching a reassurance spiral

- How to get from unilateral steps to a reassurance spiral

- Conclusion

Abstract

This policy brief examines how the United States and China could initiate a ‘reassurance spiral’ to reduce escalating tensions and mitigate the risk of military conflict. Bilateral relations are deteriorating amid growing strategic and economic competition, mutual insecurity, and reduced cooperation channels and the risks of frictions igniting conflict are on the rise. Both nations face an urgent need for reassurance strategies that credibly demonstrate benign intentions without compromising deterrence capabilities. This brief argues that reassurance is possible. Despite significant challenges—including President Trump's unpredictable policy approach and China's rigid redlines on Taiwan and maritime sovereignty disputes—current conditions may favour reassurance efforts. There are initial steps that are ‘low cost’ in that they align with domestic priorities and international commitments that could enable the two countries to reassure each other. If progress can be made, one country must make the first move—with the stronger party typically doing so—and the other must respond to create reciprocal positive momentum that could evolve into reduced bilateral tensions.

Introduction

‘Reassurance’, a strategy that when employed by adversarial states seeks to reduce the risk that a political–military crisis between them could escalate to conflict, requires that these states credibly demonstrate to each other that their intentions are not threatening. Acts of reassurance by states complement deterrence through persuasive actions that offer evidence of benign intent. Such reassurance is urgently needed to stabilize increasingly hostile relations between the United States and China. If effective, it could set in motion a dynamic between the two sides that could lead to a ‘reassurance spiral’ and perhaps to broader cooperation.

This policy brief identifies potential paths to a reassurance spiral between the United States and China. Channels for mutual reassurance continue to exist even as the two countries appear poised to further decouple their economies and tensions between them are on the rise. Despite such channels for bilateral contact, however, the security dilemma that has emerged in the relationship as each side strengthens its deterrence against the other, in combination with the securitization of national politics in both countries, has made initiating actions to foster reassurance challenging in the extreme for both sides. Nevertheless, if the United States and China were each to undertake a set of unilateral actions aimed at showing each other that they do not desire conflict, these could engender reciprocal actions that could mitigate mutual insecurity and enhance stability. The most potentially effective actions are those that both carry relatively low domestic costs and reinforce or align with domestic or international priorities for the initiating state.

This brief begins by briefly describing the need for bilateral reassurance between the United States and China and makes a case for why reassurance is possible. It then presents some ways in which each country could seek to reassure the other—recognizing that at the time of writing there is immense volatility in policy actions and reactions with respect to trade and other issues between the two countries that is certain to affect these options. It concludes by reflecting on how the potential outcomes of these efforts could set in motion a reassurance spiral that would lead to a gradual reduction in uncertainty and to diminishing perceptions of malign intentions.[1]

Background

Although normalization of Sino- American relations in the late 1970s did not resolve the sources of geopolitical tension that had prevented ties forming between the United States and China during the Cold War, the two countries characterized their increasingly multifaceted relationship as mutually beneficial for nearly four decades. While such diverging interests and frictions as the security and status of Taiwan, maritime and territorial disputes involving US allies and partners, human rights, and strategic policies were features of the relationship, the two countries managed these areas of disagreement, or ‘set them aside’ for resolution in the future, according to Deng Xiaoping’s axiom, in the interest of economic development and other ties.

Today, however, channels for cooperation between the two countries have narrowed. Mutual insecurity over a range of issues—from military intentions to economic structures, trade balances, and technological competition—has been reinforced by an increasingly sclerotic and pessimistic view of the prospects for US–China relations in both capitals. In the United States, the effectiveness of US deterrence is increasingly questioned by influential members of the Washington security policy community, who assess that China’s growing military capabilities and activities to promote its interests are aimed at securing Chinese primacy. China for its part has returned to issuing Cold War-era condemnations of US hegemony and portraying the US alliance system as a source of international division and instability. It uses its much-improved military (and paramilitary) capabilities to constrain US activities in China’s periphery and is growing its military capabilities at a rapid pace. In addition, Washington finds Beijing’s frequent use of ‘grey zone tactics’[2] to signal its resolve and or advance its interests destabilizing because grey zone activities are difficult to assess as political–military signals even as they may be fraught with potential escalatory trajectories.

Cold War lessons

Under these conditions, the two sides should pursue mutual reassurance urgently. Cold War history offers some potentially useful lessons. During that dangerous and distrustful period, the two superpowers pursued both concrete outcomes aimed at reducing each side’s sources of insecurity and diplomatic activities and processes designed to foster credibility and build trust. As James Steinberg and Michael O’Hanlon describe in their 2015 volume, Strategic Reassurance and Resolve, the United States and Soviet Union negotiated arrangements on information exchanges and transparency. They also signalled mutual restraint, finding ways to agree to limit military deployments and types of military modernization. In addition, they engaged in sustained talks on strategic arms. They worked together on an international agreement to prevent an arms race and the deployment of nuclear weapons in outer space and to sustain peaceful exploration of the space environment. Crucially, they upheld their commitments to whatever bargains they had struck.

The willingness of the United States and Soviet Union to engage in a process of reassurance is often attributed to a number of developments in the US-Soviet relationship. For one, the two Cold War superpowers had reached a point of strategic parity that does not yet exist between the United States and China and that facilitated their willingness to constrain their respective military modernization programs. In addition, the two countries experienced an acute scare in the Cuban Missile Crisis that reverberated to their respective publics, raising the domestic political stakes of failing to engage in actions to stabilize their relationship. Also adding impetus to the willingness of the superpowers to find ways to ease tensions and build trust was the shared view of Mao-led China as posing a potential common threat to strategic stability and other immediate security interests.

Current relations between the United States and China lack these features. Nevertheless, the two countries are increasingly engaged in competition in almost every possible sphere. They now compete over advances in dual use technologies and militarily across all domains—land, sea, air and space—in ways that both sides assess as existentially threatening. In Asia the two countries face off, with the United States viewing China as a direct threat to its security and those of its allies and China perceiving US strategy as aimed at threatening its economic security and sovereignty and compromising its internal security.[3] Tensions over Taiwan are the highest they have been since normalization. Bilateral economic relations are no longer the source of ballast in the relationship they once were. In this context, in recent years, the two countries have begun to test each other’s redlines while also reducing official dialogue, behaviours that increase the likelihood that crises may escalate into conflict.

As Kai He observes in his Toda policy brief, it is possible that leaders in both Washington and Beijing may engage for a variety of reasons in risk-taking behaviour; they are both capable of making bold and provocative decisions.[4] It seems likely that they will continue policies that bolster their countries’ respective deterrent capabilities. However, both have conveyed a preference for international behaviour that avoids war. It is also possible that they may be willing to engage in actions aimed at reducing mutual suspicions as long as these align with other policy goals or garner other benefits.

Launching a reassurance spiral

Under these conditions, the most effective way (and perhaps the only realistic way) of launching a process of reassurance is for each side to begin with unilateral actions that have modest costs relative to potential benefits. Several low-cost, high-gain steps by each country could help foster conditions for more politically challenging but higher-gain actions that could set in motion an upward reassurance spiral. Notably, most of the lower- and moderate-cost actions to the initiating state involve steps that require little more than statements at the leadership level.

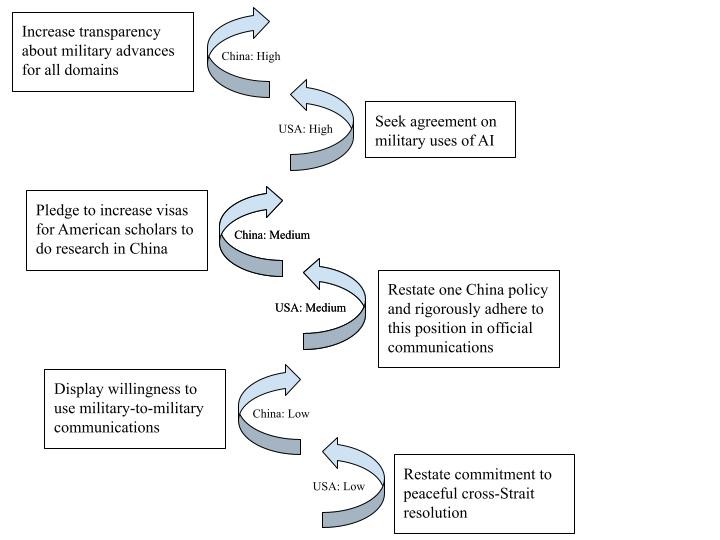

Tables 1 and 2 present illustrative lists of possible actions by Washington and Beijing, the costs (low, moderate or high) associated with these actions, and their prospective outcomes—outcomes that are possible based on the author’s assessment and may be considered best-case scenarios.

If undertaken, the unilateral steps shown in Table 1 would demonstrate an unambiguous readiness by the United States to reduce tensions. Another step in the same direction would be to share information with China about imminent US military and security developments that could affect stability. The United States could also unilaterally take verifiable action to restrain its own deployment of some capabilities that could harm China, such as refraining from expanding missile defence in the Indo-Pacific, making clear to China that such action is a gesture aimed at cultivating reassurance.

Table 1. Costs and likely outcomes of potential US actions to foster reassurance

| US Actions | Cost | Best Case Outcomes | Explanation for Costs Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restate commitment to peaceful cross-Strait resolution | Low | Reinforces long-standing agreements that are the basis for normal bilateral relations. | The US public supports peaceful cross-Strait relations even as rising numbers of Americans support defending Taiwan. Peace in the Taiwan strait is longstanding US policy.[5] |

| Routinize surveillance flights and transits and signaling on freedom of navigation | Low | Would increase predictability, thereby reducing the risks of inadvertently generating a crisis. | Many experts have argued for making these activities more routine in the interest of reducing the risk of crises, with one US naval officer usefully describing the difference as moving from a ‘SWAT’ team approach to a ‘beat cop’ approach.[6] |

| Increase leader interaction and routine civilian and military diplomacy | Low | Strengthens personal relationship between the leaders, which could build trust, and expands routine political contact. | The hard line taken on China by most US officials through successive administrations has reduced the political costs of talks aimed at managing tensions and resolving areas of disagreement. |

| Seek to reinforce rules for air/ maritime encounters | Low | Should increase predictability and reduce the potential of inadvertently generating a crisis. | Existing multilateral and bilateral arrangements exist codifying ‘rules of the road’; China has often disregarded these rules. As bilateral tensions have risen the escalation potential has increased the stakes for the US.[7] |

| Declare no pursuit of regime change | Moderate | Should obviate the need for China to signal its disapproval of and respond to calls for regime change. | There is weak US public support for direct intervention to change other countries’ governments with largely negative assessments of the recent US wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.[8] No US president or senior official has explicitly advocated for regime change in China nor have members of Congress called for the overthrow of the CCP. |

| Restate one China policy and rigorously adhere to this position in official communications | Moderate | Would meet with significant approval in Beijing, albeit while generating opposition from domestic political circles, including key figures in Congress, that seek to expand political and strategic ties with Taiwan. | The US government, including the US Congress, has affirmed the US commitment to the one China policy. However, there is strong bipartisan support for Taiwan that varies mainly in the degree to which members of both parties support the use of US military assets to defend Taiwan in a cross-strait crisis.[9] |

| Seek agreement on military uses of AI | High | Would be major undertaking that could be political fraught; differences in US and Chinese models for developing AI would make an agreement difficult to harmonize.[10] | Bipartisan majorities in Congress have maintained the US export control regime on AI, as have successive moves by the Biden and Trump administrations. A reversal of this effort would contravene years of US policy toward China and risk criticism that the Trump administration is going ‘soft’ on Xi Jinping.[11] |

| Promote civilian space cooperation in multilateral forum | High | Runs counter to interpretations of existing US legislation and may require expending political capital. | Any direct US government collaboration with China on space policy requires an exemption from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which poses a political risk for the Trump administration. This is because in order to grant the exemption, the FBI has to certify that the Chinese interlocutors are not a threat to steal intellectual property or commit human rights abuses; both claims are central to longstanding Republican policy on China.[12] |

| Engage in strategic stability talks with China | High | President Trump has sought trilateral talks also involving Russia; unclear if bilateral talks are an option and would require US–Russia talks to restart. | Given that in 2024 China canceled arms control talks with the United States over weapons sales to Taiwan, it is unlikely China would engage unless US policy towards Taiwan shifts. President Trump may be willing to do that, especially after showing an ability to buck his party on Ukraine, but the political costs would be high given substantial bipartisan support for Taiwan in Congress. |

For China’s part, several low-cost, high-gain actions are possible, as illustrated in Table 2. These could be the basis for more politically challenging, high-cost actions, some of which are also suggested in Table 2. Each chart presents an explanation for the likely potential costs to the two sides.

Table 2. Costs and likely outcomes of potential Chinese actions to foster reassurance

| PRC actions | Cost | Best Case Outcomes | Explanation for Costs Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Display willingness to use military-to-military communications | Low | Would serve as a CBM between the two militaries; precedent for this with the US and other countries. | On the one hand, Xi has made military-to-military communications between China and other countries a function of positive or warming bilateral relations, often cutting off access or declining to use existing hotlines during crises.[13] Whenever China is upset about US policy toward Taiwan, military hotlines are often one of the first mechanisms affected.[14] On the other hand, China has also pursued negotiations on hotlines or reopening military-to-military dialogues when it has sought to improve US–China ties. |

| Seek and engage in bilateral and multilateral talks on developing guidelines for military use of AI and other emerging technologies | Low | There is strong international support for international talks but potential for engaging the US is low. The Trump administration may perceive political and security costs as too high and eschew multilateral talks. | Chinese government policy plays a leading role in supporting the development of AI in China. Beijing’s support has been accompanied by the among the world’s ‘earliest and most detailed’ AI governance measures giving it exceptional experience in this area.[15] |

| Pledge to increase visas for American scholars to do research in China | Medium | Reverses negative trend in people-to-people ties and shows Xi’s China as more open and inviting for foreigners. | Chinese interest in giving foreign researchers access has long been declining, so such a change would be a significant one. An influx of foreign scholars could also pose security concerns if they focus on politically sensitive domestic topics. Policing these scholars would pose freedom of expression concerns that essentially defeat the purpose of inviting them in the first place. |

| Allow return of select journalists from American news outlets | Medium | Demonstrates a loosening-up of the environment in Xi’s China. | China certainly would not welcome more critical news coverage from Western news outlets, so there is a risk to giving visas to more journalists. But the current policy has not dampened critical news stories and, if anything, has shined more of a spotlight on Taiwan as Western news reporters have moved there to cover the mainland. |

| Increase transparency about planned military operations; reduce grey zone activities | High | Beijing must be persuaded it would not lose ground. | Although China has largely telegraphed its large-scale military exercises around Taiwan, usually timing them around major events like Taiwan’s National Day, neither the planning nor enactment of these operations are likely to be part of a negotiation.[16] China’s intensifying propaganda campaign against Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and DPP president, Lai Ching-te, makes a move in this direction all the more challenging to Beijing. |

| Increase transparency about military advances for all domains | High | Counter to general posture preferencing secrecy on military modernization. Once reciprocity on this is agreed to, both sides must uphold it as the costs of violation are high. | China has little reason to be transparent with the United States on military issues. This is especially the case given the apparent turmoil in the PLA’s top ranks (evidenced by the many purges Xi has conducted in recent months). There is also the risk that taking this step at a time of slightly better relations with the United States could backfire if relations worsen. |

| Engage in strategic stability talks with the United States | High | Nuclear talks with the US would be a shift in Chinese policy and may be politically challenging amid a view that a lack of transparency enhances US perceptions of China’s nuclear capabilities. However, benefits extend to regional neighbours impacted by China’s lack of transparency. | China has shown virtually no interest in serious arms control talks with the US given the disparity in the US and Russia’s nuclear arsenals compared to China’s.[17] While engaging in talks may not pose much political risk, there is a chance China’s adversaries would be emboldened by what would appear to be a unilateral concession on arms control. |

How to get from unilateral steps to a reassurance spiral

While the kinds of actions identified in Tables 1 and 2 may be possible, how likely are the two countries to undertake them and how might they generate positive momentum toward increasing reassurance?The answer depends at least in part on identifying not only the reasons why Washington and Beijing may shy away from reassurance but also the ways in which reassurance-oriented activities can resonate with other policies and preferred approaches.

Figure 1: Reassurance Spiral

Among the key challenges from China for the United States in developing a reassurance spiral is Beijing’s commitment to its declared redlines on Taiwan and its rigidity on maritime claims. When actions by other countries are deemed to cross those redlines and infringe upon those claims, Beijing is likely to respond in a way that is far from reassuring for the United States and its allies and partners. Another challenge is the Chinese Party-State’s preference for information control and low transparency, which does not create a propitious environment for reassurance.

Among the key challenges for China from the United States in building a reassurance spiral are President Trump’s track record of rapidly changing policy course and his ability to do so given the power he wields across all three branches of the US government. China may not be willing to risk the potential political complications for Xi Jinping of apparent failures by the United States to carry out agreements; equally, Beijing may not want to invest heavily in diplomacy only to see it fall by the wayside in a Trump policy pivot.

However, current signs are that the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, perceives a less volatile, less risk-prone relationship with the United States to be in China’s interests. China may assess that adopting a less assertive posture in its periphery—holding firm but being less focused on altering the facts on the ground to serve its claims—is in its interests in the immediate term so that it can engage the United States in reassurance activities. In addition, although the Trump administration’s policies are still taking shape and may continue to fluctuate, Trump returned to the White House in 2025 with a track record of transactionalism in international relations, as displayed in dealings with countries ranging from strategic competitors to allies and partners. The emphasis placed by Trump on personal leader-to-leader interactions Trump’s preference for unilateral action, bargaining and tit-for-tat moves may enable steps toward reassurance. And if President Donald Trump has other policy goals that can be moved forward if his personal relationship with Xi is strengthened and relations with China are less crisis prone, he may be willing to exercise his authority to pursue reassurance.

Even if a process of reassurance is possible, a critical hurdle would nevertheless need to be overcome for a reassurance spiral to be launched: one of the two countries would have to make the first move. Studies of reassurance suggest that they are often animated when the stronger of the two parties takes the initiative. One scenario would be for Washington to take the first step by signaling interest to Beijing in reducing tensions. China would likely be more comfortable if the United States did so as this dynamic would be consistent with frequent Chinese behaviour in the US–China relationship whereby during periods of intense bilateral tension or outright crises, China has preferred to react to US initiatives. Although at the time of writing, it is unclear if a ‘ceasefire’ in the US–China trade war will ultimately lead to a more durable economic détente between the two countries, it appears that US outreach to China led to the roll back in tariffs between the two countries in mid-May 2025. The United States might undertake one or two low-cost measures toward reassuring China that might be in the form of remarks by President Trump or a top US official, for example. Trump has demonstrated he is open to bold negotiations on the international stage. In addition, China has more to gain than to lose through a constructive response and is likely to respond with a low-cost move of its own.

Conclusion

Given President Trump’s predilection for conducting international relations from his gut, making predictions is especially difficult. But with the high-level trade negotiations between the United States and China on the table, the two countries have an opportunity to undertake low-cost measures toward reassurance—and perhaps greasing the wheels for a trade deal.

The menu of options outlined in Figure 1 could suit Trump, who—despite his free-wheeling use of sanctions and other tools of economic leverage—has been critical of more hawkish Republicans and apparently disinterested in leveraging military tensions with major powers. This may make him amenable to low-cost moves aimed at decreasing tensions over Taiwan and restoring normalized military-to-military talks with China.

Whatever progress both sides make will depend on their ability to establish mutual confidence. If the US is to make progress, it has to show a willingness to keep its word. And Xi, now wise to Trump’s ways after the experience of the American president’s first term, is likely to see a negotiation that veers off course before coming back again as standard practice for Trump.

The risk of tensions and crises generating an escalation spiral between the United States and China has been intensifying. A series of small moves, such as those proposed in this essay, each aimed at reassuring the other party, could have significant payoffs in stabilizing what remains the world’s most consequential relationship.

Notes

[1] Kai He, "US-China Reassurance: Theory and Practice,” Toda Peace Institute, March 31, 2025, https://toda.org/policy-briefs-and-resources/policy-briefs/report-217-full-text.html.

[2] Defined as "attempts to achieve one’s security objectives without resort to direct and sizable use of force” in John Schaus, John, Heather A. Conley, Michael Matlaga, and Kathleen H. Hicks. 2024. "What Works: Countering Gray Zone Coercion.” https://www.csis.org/analysis/what-works-countering-gray-zone-coercion from Michael J. Green, Kathleen H. Hicks, Zack Cooper, John Schaus, and Jake Douglas, Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia: The Theory and Practice of Gray Zone Deterrence (Washington, DC: CSIS/Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

[3] See U.S. Department of Defense. n.d. "China’s Military Buildup Threatens Indo-Pacific Region Security.” https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4150802/chinas-military-buildup-threatens-indo-pacific-region-security/; Sim, Dewey, and Dewey Sim. 2024. "What Is China’s Biggest Security Threat? The US, Says a Top Chinese Researcher.” South China Morning Post, November 1, 2024. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3284798/what-chinas-biggest-security-threat-us-says-top-chinese-researcher.

[4] He, 2025.

[5] Craig Kafura, "On Taiwan, Americans Favor the Status Quo," Chicago Council on Global Affairs, October 2024, https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/taiwan-americans-favor-status-quo; Congressional Research Service, "Taiwan: Background and U.S. Relations," IF10275 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, May 23, 2024), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF10275

[6] Captain Joshua Taylor, "A Campaign Plan for the South China Sea," Proceedings 148, no. 8 (August 2022), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/august/campaign-plan-south-china-sea.

[7] Mark E. Redden and Phillip C. Saunders, "Managing Sino-U.S. Air and Naval Interactions: Cold War Lessons and New Avenues of Approach,” China Strategic Perspectives, no. 5 (National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies), https://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-5.pdf.

[8] "Eighty Years after D-Day: American Perspectives on U.S. Wars," YouGov, June 6, 2024, https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/49639-eighty-years-after-d-day-american-perspectives-us-wars-vietnam-iraq-wwii-wwi-poll; Evan S. Medeiros and Ashley J. Tellis, "Regime Change Is Not an Option in China," Foreign Affairs, July 8, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/asia/regime-change-not-option-china.

[9] Craig Kafura, Dina Smeltz, Jordan Tama, and Joshua Busby, "Republican Foreign Policy Experts Signal Strong Support for Taiwan," Chicago Council on Global Affairs, https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/republican-foreign-policy-experts-signal-strong-support-taiwan.

[10] Mathew Jie Sheng Yeo and Hyeyoon Jeong, "Can China and the US Find Common Ground on Military Use of AI?," The Diplomat, July 18, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/07/can-china-and-the-us-find-common-ground-on-military-use-of-ai/.

[11] Ana Swanson, "Lawmakers Press Biden Administration for Tougher Curbs on China Tech," New York Times, December 7, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/07/us/politics/lawmakers-biden-china-tech.html

[12] "Biden Advisers Urge Working With China in Space," Politico, December 20, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/12/20/biden-china-space-448529.

[13] Examples include military-to-military hotlines with Japan and the Philippines: N.a., "Urgent: Hotline Not Used Over Japan Airspace Breach by China Military Plane," Kyodo News, September [day], 2024, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2024/09/803954b91803-urgent-hotline-not-used-over-japan-airspace-breach-by-china-military-plane.html; Raissa Robles, "South China Sea: Hotlines Exist, but Philippines Says Beijing 'Does Not Answer,'" South China Morning Post, July 17, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3270819/south-china-sea-hotlines-exist-philippines-says-beijing-does-not-answer.

[14] Examples of this include: Dzirhan Mahadzir, "China Refuses Austin Meeting Request Over Arms Sale to Taiwan," USNI News, November 21, 2024, https://news.usni.org/2024/11/21/china-refuses-austin-meeting-request-over-arms-sale-to-taiwan; Ellen Knickmeyer, David Rising, and Zeke Miller, "China Cuts Off Vital U.S. Contacts Over Pelosi Taiwan Visit," PBS NewsHour, August 5, 2022, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/china-cuts-off-vital-us-contacts-over-pelosi-taiwan-visit.

[15] Matt Sheehan, “China’s AI Regulations and How They Get Made,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 10, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/07/chinas-ai-regulation.

[16] Helen Davidson and Chi-hui Lin, "China Military Taiwan Drills President Lai National Day Speech," The Guardian, October 14, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/oct/14/china-military-taiwan-drills-president-lai-national-day-speech.

[17] Matthias Hammer, "China Declines to Meet with US on Nuclear Arms Control, US Official Says," Semafor, May 1, 2024, https://www.semafor.com/article/05/01/2024/china-declines-to-meet-with-us-on-nuclear-arms-control-us-official-says.

References

Blankenship, Brian. "Promises under Pressure: Statements of Reassurance in US Alliances.” International Studies Quarterly 64, no. 4 (December 2020): 1017–1030.

Glaser, Bonnie S., Jessica Chen Weiss, and Thomas J. Christensen. "Taiwan and the True Sources of Deterrence: Why America Must Reassure, Not Just Threaten, China." Foreign Affairs 103 (2024) (On-line).

He, Kai, "US-China Reassurance: Theory and Practice,” Toda Peace Institute, March 31, 2025, https://toda.org/policy-briefs-and-resources/policy-briefs/report-217-full-text.html.

Medeiros, Evan S. and Ashley J. Tellis, "Regime Change Is Not an Option in China," Foreign Affairs, July 8, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/asia/regime-change-not-option-china

Montgomery, Evan Braden. "Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma: Realism, Reassurance, and the Problem of Uncertainty." International Security 31, no. 2 (2006): 151–185.

Redden, Mark E. and Phillip C. Saunders, "Managing Sino-U.S. Air and Naval Interactions: Cold War Lessons and New Avenues of Approach," China Strategic Perspectives, no. 5 (National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies), https://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-5.pdf.

Stein, Janice Gross. "Reassurance in International Conflict Management." Political Science Quarterly 106, no. 3 (1991): 431–451

Steinberg, James, and Michael E. O’Hanlon. Strategic Reassurance and Resolve: US-China Relations in the Twenty-first Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Wuthnow, Joel. "Shield, Sword, or Symbol: Analyzing Xi Jinping’s ‘Strategic Deterrence.” Brookings, March 7, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/shield-sword-or-symbol-analyzing-xi-jinpings-strategic-deterrence/

Zhao, Tong. "Underlying Challenges and Near-Term Opportunities for Engaging China." Arms Control Today 54, no. 1 (2024): 6–11.

The Author

CARLA FREEMAN

Dr. Carla Freeman is Senior Lecturer for International Affairs and Director of the Foreign Policy Institute at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (JHU SAIS). Prior to her current role at SAIS, she held a variety of academic and non-profit positions, most recently as Senior Expert for China at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and Library of Congress Kluge Chair in US–China Relations. She began her career as a risk analyst, She is the author of numerous scholarly and policy publications on Chinese foreign and security policy.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org