Social Media, Technology and Peacebuilding Report No.211

Mapping Digital Pathways to Peace: Exploring the PeaceTech in Sri Lanka

Emma Jackson

March 02, 2025

Abstract

This report examines the landscape of digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka, exploring how technology is being leveraged to promote social cohesion, social justice, and human security in a post-war context. Through a literature review and over 30 interviews with stakeholders, the research maps existing digital peacebuilding initiatives and analyses their potential contributions as well as challenges. Key findings highlight innovative uses of social media, digital literacy programs, and online platforms to counter hate speech, misinformation, and bridge societal divides. However, significant obstacles remain, including the digital divide, language barriers, funding constraints, and government restrictions on online spaces. The paper concludes with recommendations for advancing digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka through multi-stakeholder collaboration, contextualized approaches, and ethical use of technology. This research contributes to the emerging field of digital peacebuilding by providing insights from the Sri Lankan case on both the promise and limitations of leveraging technology for peace.

Contents

- Introduction

- How technology is used for violence in Sri Lanka

- Mapping the digital peace ecosystem: How peacetech can promote social cohesion, social justice and human security

- Challenges for digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka

- Opportunities and recommendations for digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka

Introduction

This study undertakes an analysis of current digital peacebuilding efforts, evaluating their potential and constraints within the Sri Lankan context. Digital peacebuilding refers to the use of digital technology in the practice of peacebuilding, which includes democratic deliberation, violence prevention, social cohesion, civic engagement, and improved human security.[1] This study also investigates the potential of peacetech initiatives in Sri Lanka, a country with a rich history of tech innovation. Peacetech is technology that contributes to peacebuilding.[2] The study aims to provide insights into effective strategies for utilizing technology in peace processes within the Sri Lankan context.

RESEARCH INTEREST AND PROBLEM

The conflict in Sri Lanka stems from a history of colonization and ethnic tensions. Post-independence from British rule in 1948, tensions between the Sinhalese and Tamil minorities escalated. The Tamil community faced marginalization and discrimination as the Sinhalese-dominated government enacted laws restricting the Tamil language and political representation, leading to anti-Tamil pogroms in the 1960s. The conflict intensified in 1983 with anti-Tamil riots, sparking a 26-year civil war between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a militant separatist group fighting for an independent homeland for Hindu Tamils, and the Sinhala Buddhist majority government, resulting in an estimated 100,000 deaths.[3] Despite the war's end in 2009 following a major military offensive, the Tamil community continues to endure discrimination and human rights abuses, including tens of thousands of enforced disappearances.[4] Since the war ended, successive Sri Lankan governments have introduced various reconciliation commissions and frameworks. However, minority communities and human rights groups often view these efforts as attempts to lessen international scrutiny rather than genuine initiatives for lasting peace and reconciliation.[5]

Recent years have seen a rise in Buddhist nationalism and widespread anti-Muslim violence.[6] In March 2018, anti-Muslim riots were incited via social media platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp. The April 2019 Easter Sunday attacks by a local Islamic extremist group, linked to the Islamic State, killed approximately 269 people. [7] In response, the government imposed a social media ban to curb disinformation. Content inciting hate, online gender-based violence (OGBV) and hate speech against ethnic and gender minorities are pervasive issues. Furthermore, the surveillance and harassment of journalists, activists, civil society groups, and minorities based on gender, ethnicity, and religion raise significant concerns. These practices contribute to a 'chilling effect' that constricts civic and democratic spaces, promoting self-censorship.[8]

In 2022, the country experienced its worst economic crisis since independence, causing widespread food insecurity and public demands for government accountability.[9] Public protests evolved into the ‘Aragalaya’ movement, derived from the Sinhalese term for “struggle”.[10] The government violently suppressed these initially peaceful protests, which later turned violent. Consequently, the information ecosystem became saturated with misinformation and disinformation.

The persistent, deep-seated divisions, trauma, and fear along ethnic and religious lines underscore the necessity for sustained and inclusive peacebuilding efforts.[11] While civil society actors have been utilizing peacetech to promote social cohesion, social justice, and human security for years, there is a limited understanding of the broader digital peacebuilding landscape in Sri Lanka, including how technology can be effectively used for peacebuilding and the challenges and opportunities associated with its implementation

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND METHODOLOGY

This report emerges from research that took place in Sri Lanka in 2022 and 2023. The central research question explored how Sri Lankan's use of digital peacebuilding might contribute to peacebuilding efforts in Sri Lanka. To address the central research question, this research project explores the following sub- questions:

(1) How can peacetech initiatives be effectively utilized to promote social cohesion, social justice, and human security in Sri Lanka?

(2) What are the challenges and opportunities for digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka?

(3) How can collaboration and innovation in digital peacebuilding among different sectors and organizations improve peacebuilding and reconciliation outcomes in Sri Lanka?

The research started with a literature review and 30 interviews involving diverse local stakeholders in digital peacebuilding, including civil society representatives, social impact professionals, tech engineers, habitual social media users, and consultants at the intersection of technology and society.

This research methodology faced limitations due to the positionality of the author as an American with limited fluency in local languages, initially confining the interviews to predominantly English-speaking participants. The author addressed this challenge by traveling across Sri Lanka to engage with Sinhala, Tamil, and Muslim communities with the assistance of a translator. The descriptions of peacetech initiatives may incorporate sentiments and opinions from respondents; the author clarifies that these are not her personal evaluations, which would necessitate a more rigorous analysis.

The situation in Sri Lanka showcases a complex interplay of the use of technology and social media, government policy, and societal tensions, where digital tools not only exacerbate divisions but also allow disinformation to catalyze physical violence and conflict.

How technology is used for violence in Sri Lanka

Reviewing the history of technology and violence in Sri Lanka is essential to understand the landscape and potential for digital peacebuilding. The situation in Sri Lanka showcases a complex interplay of the use of technology and social media, government policy, and societal tensions, where digital tools not only exacerbate divisions but also allow disinformation to catalyze physical violence and conflict. Digital platforms can propagate ‘information disorder,’ a term that describes the nuances between misinformation (false information shared without harmful intent), disinformation (deliberately misleading information), and malinformation (based on reality, used to inflict harm on a person or organization).[12] Concurrently, these technologies provide vital platforms for activism and resistance.[13]

Disinformation on social platforms has been linked to deadly violence in Sri Lanka. In March 2018, social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp exacerbated deadly anti-Muslim riots in Sri Lanka by failing to control the spread of disinformation and hate speech inciting violence.[14] Facebook has been criticized for inadequate content moderation in Sri Lanka, including their failure to remove content that promoted violence against Muslims.[15] Disinformation also fueled Buddhist nationalist hate speech against Muslims, which escalated following the Easter Sunday attacks on churches and hotels that killed 269 people in April 2019.[16]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a policy mandating the forced cremation of those who died from the virus led to further disinformation and hate speech against Muslim communities online.[17] Similarly, during the onset of the 2022 economic and political crisis, youth activists were falsely accused of being separatists, terrorists, or drug addicts, exacerbating communal divisions and distracting from government mismanagement and corruption that precipitated the crisis.[18]

An activist in Sri Lanka mentioned during the 2022 crisis and Aragalaya social movement: “If there was a place where there was an obstacle or where there was a situation where we had to take a step back [during the Aragalaya], it has always been because of things like opinions and misinformation where Sri Lankans tend to act on rumors rather than facts.”[19] The spread of disinformation can exacerbate ethnic and religious tensions and amplify conflicts, particularly as the vast amount of content generated during crises makes verification nearly impossible.

Sri Lanka has grappled with ongoing gender-based violence, particularly targeting young women, the LGBTQ+ community, and female politicians, which intensified during the 2022 economic and political crisis.[20] OGBV is a significant challenge, especially for marginalized communities in Sri Lanka's Northern and Eastern regions. [21] A study in 2020 and 2021 on the online space for Sri Lankans in the LGBTQ+ community released a survey that revealed that 62% of respondents had received abusive comments online, while 56% reported receiving unwanted pornographic, sexually explicit, or demeaning images.[22] More than 90% of respondents affected by abuse would not report it to any legal mechanism or system as they felt that the justice system does not hold perpetrators accountable.[23] Seeking support from institutions can lead to further shaming, stigma, or prejudice, deterring victims from coming forward. Moreover, OGBV is becoming normalized, particularly in LGBTQ+ communities, and data is lacking due to underreporting and fear of discrimination.[24] The country also has low digital literacy levels, and cultural reasons often prevent people from speaking up.[25] Addressing the root causes of OGBV is essential, particularly for marginalized communities in Sri Lanka, as the online world mirrors the offline world.

The volume, variety, and velocity of online content production makes it exceedingly difficult to effectively monitor and mitigate dangerous speech.[26] Once published, hate speech often spreads and morphs across various websites and platforms, a process that can be accelerated by generative AI. Thus, removing the original post does not guarantee its complete eradication, making it difficult to fully eliminate its traces.[27]

The government has placed restrictions on social media in times of crisis. In April 2022, amidst widespread protests demanding his resignation due to the economic and political crisis, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa declared a state of emergency, granting extensive powers to security forces and imposed restrictions on social media, after protesters defied a nationwide curfew to demand government accountability.[28][29] Shortly after the ban was lifted, activists experienced a surge in harassment and inauthentic behaviors, including coordinated disinformation campaigns orchestrated through pro-government actors.[30]

This is not the first instance where the Sri Lankan government has restricted social media. Following the Easter Sunday attacks in 2019, the government blocked social media to curb the spread of disinformation, extremism, and incitement to violence.[31] However, banning social media or the internet is no panacea for misinformation, which ultimately puts those already vulnerable in a worse position. Restricting access to social media raises larger questions about the risk of violence versus access to free information. In times of crisis, people need to seek out information and connect with loved ones to feel safe, particularly in a country like Sri Lanka, where most everyday communications are through Facebook and WhatsApp.[32]

The impact of such government actions is exacerbated by the role of social media, where harmful rhetoric from politicians has fueled mistrust, division and violence, particularly targeting ethnic and religious minorities

The Sri Lankan government has a history of leveraging social media regulation not only to combat disinformation but also to suppress dissent and promote ethnonationalist discourse, raising concerns about censorship and the undermining of democratic processes through information control.[33][34] Sri Lankan politicians have also been involved in practices that contribute to heightened tensions along identity lines through surveillance, intimidation, and media manipulation.[35] Reports indicate that there has been consistent governmental surveillance and harassment of victims, activists, and media personnel, which has contributed to a lack of trust and reconciliation efforts.[36] The impact of such government actions is exacerbated by the role of social media, where harmful rhetoric from politicians has fueled mistrust, division and violence, particularly targeting ethnic and religious minorities.[37][38]

Policies such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), enacted in 1979, empowers authorities to detain individuals without charge for up to 18 months and restrict communication channels like internet access, primarily targeting Tamil and Muslim communities.[39] These laws have intensified the harassment and intimidation of activists, fostering a climate of self-censorship and impeding advocacy for marginalized communities in Sri Lanka.[40]

The contentious Online Safety Act (OSA), passed in 2024, grants a government-appointed commission broad powers to determine and remove "prohibited" online content.[41] Protests erupted outside the parliament as the bill was passed, reflecting widespread alarm.[42] More than 50 civil society organizations and tech industry coalitions issued an open letter to demand the government withdraw the rights-violating OSA.[43] This letter highlighted the threats to democratic processes and human rights by suppressing online dissent, particularly during elections, and the potential for exacerbating Sri Lanka's economic challenges by hindering digital opportunities.[44] While amendments to the OSA introduced judicial oversight and removed some harsher penalties, critics argue these changes fail to address fundamental flaws that pose an unprecedented threat to freedom of expression and other human rights.[45] Uniquely severe in its scope and potential for abuse, the Act introduces significant and disproportionate risks for women, LGBTQ communities, and ethnic minorities. [46][47]

With the 2024 election of President Dissanayake, prominent civil society groups called for the abolition of the OSA and the PTA. Disinformation experts like Dr. Sanjana Hattotuwa stressed the importance of a complete overhaul, arguing that vague definitions and insufficient safeguards risk arbitrary censorship and suppression of free expression.[48] Hattotuwa has also proposed a necessity and proportionality framework, judicial oversight, and multi-stakeholder governance to ensure fairness in regulatory frameworks that both address online harms and simultaneously align with international human rights standards.[49]

Mapping the digital peace ecosystem: How peacetech can promote social cohesion, social justice and human security

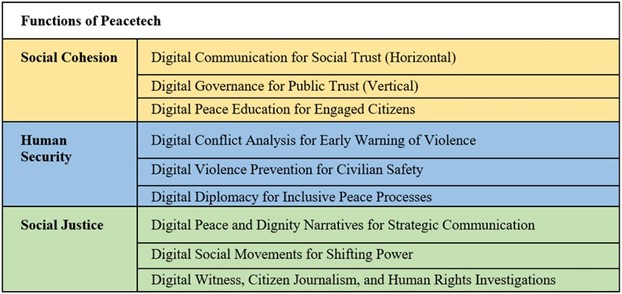

Sri Lankans have been leveraging technology, the internet, and new media to support democracy, peacebuilding, and community development, including initiatives addressing online hate speech, OGBV, and promoting digital literacy to address mis- and disinformation since the early 2000s.[50] Drawing on Lisa Schirch’s “Functions of PeaceTech” framework, the next section of this report offers examples of the many peacetech in Sri Lanka.

Source: Schirch, Presentation on Mapping Technologies for Peace, and Conflict, Feb 3, 2022

PEACETECH FOR SOCIAL COHESION

Digital communication for social trust (horizontal)

Digital communication is a vital tool for fostering social trust and peaceful coexistence in Sri Lanka. Youth-led initiatives and social impact organizations are leveraging digital platforms to counter hate speech and facilitate dialogue across diverse communities.[51] One notable initiative is Work Together Win Together, a project by Search for Common Ground (Search) Sri Lanka, which has trained 1,200 youth in digital peacebuilding and media literacy through over 20 boot camps.[52] Participants gained skills to identify and respond to hate speech using nonviolent communication and dialogue. Their efforts resulted in social media campaigns that reached over 3.4 million people, fostering conversations among youth from varied backgrounds and promoting trust and understanding.[53] Another program, Women in Technology, also led by Search Sri Lanka, creates safe online spaces for young women leaders to share ideas and counter hate speech through campaigns.[54]

DreamSpace Academy, a social impact startup incubator, supports projects like iReact, HER, and AI-driven initiatives that drive local positive change. By empowering youth from different ethnic, religious and gender backgrounds, to play an active role in developing peacetech projects, this project seeks to make a tangible impact on social cohesion in Sri Lanka.[55]

These initiatives demonstrate the powerful potential of digital communication in fostering social trust and encouraging inclusive dialogue. By empowering youth, women, and marginalized communities with the skills to navigate online challenges, these efforts can contribute to a more inclusive online environment where trust and social cohesion can flourish.[56]

Digital governance for public trust (vertical)

Digital Governance for Public Trust focuses on leveraging digital tools and systems to enhance transparency, accountability, and public participation in governance processes, ensuring that technology fosters greater trust between citizens and their governments.

In 2024, the Dissanayake Government announced that the country will undergo a digital transformation in the next three years to drive economic growth.[57] This includes an announcement to implement a nationwide digital ID system and aims to digitize the country’s economy, streamline government services, emphasizing its potential to address challenges such as corruption and inefficiency in public services.[58] The 2022 Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) establishes a regulatory framework for managing personal data, emphasizing the protection of individual privacy and imposing strict obligations on data controllers and processors.[59] This legislation aims to empower individuals with control over their information and ensure responsible data handling practices by organizations.[60] These developments have the potential to enable more transparent governance and government accountability, improve data privacy for citizens, and foster increased public trust.[61]

Digital peace education for engaged citizens

Digital peace education is a key component of Sri Lanka's peacetech initiatives, promoting social cohesion and community engagement. Peacebuilding-informed digital media literacy programs and the use of digital tools enable citizens to challenge harmful narratives and promote understanding across diverse groups. The We-gital Heroes Youth in Digital Peacebuilding project by Search Sri Lanka, empowered youth to counter dangerous online speech through training, mentorship, and collaborative social media campaigns, all hosted on a digital edutainment LMS platform. The initiative trained 365 youth (58% from marginalized communities), was used by over 1,000 unique users, and supported 12 youth-led projects addressing topics like AI, online safety, and inclusion.[62]

Collaborative efforts, such as the Get the Trolls Out project led by Media Diversity Institute and Hashtag Generation, aimed to foster social cohesion in Sri Lanka by developing critical thinking skills among online audiences and building resilience to harmful narratives propagated by social media.[63][64] Additionally, IREX’s Media Empowerment for a Democratic Sri Lanka (MEND) program and Learn to Discern initiative has equipped students, teachers, and journalists with critical media literacy skills, enabling them to identify and resist disinformation, and seek balanced, reliable and objective news.[65][66] The International Center for Journalists' Disarming Disinformation initiative resulted in a youth-led project, Digizen, which focuses on enhancing digital literacy, internet security, and ethical online engagement.[67]

These programs highlight the transformative potential of media literacy and peace education in promoting critical thinking, community resilience, and the broader goals of peacebuilding in Sri Lanka.

PEACETECH FOR HUMAN SECURITY

Peacetech for human security includes various tools such as digital conflict analysis for early warning of violence, digital violence prevention for civilian safety, and digital diplomacy for inclusive peace processes.

Digital conflict analysis for early warning of violence

Digital conflict analysis uses technology and data analytics, including satellite imagery, social media, and news reports, to predict and assess potential conflicts and enable proactive interventions by identifying early signs of conflict.

Shortly after a ceasefire in 2002, the Foundation for Co-existence implemented a conflict early warning system in Sri Lanka’s Eastern province amidst the civil war, involving local actors to collect, verify, and analyse data for violence prevention. Initially successful in preventing violence with the support of interethnic and interreligious committees, the system's effectiveness waned as the war re-intensified, with reliable information becoming scarce and preventative measures challenging to implement.[68]

Groundviews utilized Google Earth’s satellite imagery to analyse and document destruction and mass graves towards the end of the civil war.[69] Harnessing satellite imagery to capture and share visual evidence of mass graves in so-called ‘Civilian Safe Zones’helps preserve collective memory and provided poignant reminders of the destructive impact of war.[70] This contributes to archiving conflict history for educational and memorial purposes, helping to honour and remember the dead. Satellite imagery as a form of peacetech also enables access to critical information in otherwise inaccessible areas, aiding more effective policy decisions, efforts to prevent violence and implement informed humanitarian interventions.

Digital violence prevention for civilian safety

During the Aragalaya, civil society organizations, such as Hashtag Generation, launched initiatives to protect civilians during protests. They ran campaigns to educate people on defending themselves against tear gas and police brutality, and informed them of their protest rights, providing contacts for pro-bono attorneys in case of unwarranted arrests. Individual influencers and activists widely circulated Instagram posts and TikTok videos designed to prevent violence and encourage peaceful protest, even in the face of unjust actions by security forces.[71]

Prathya is an online ecosystem of support for persons affected by OGBV in Sri Lanka developed by Hashtag Generation and Delete Nothing and launched in November 2022.[72] Prathya provides trilingual support services to women, girls, trans, and queer people affected by online violence. Prathya has a three-pronged approach to provide technical support (e.g., removing and reporting a harmful post), legal support (e.g., to address cyber-stalking or harassment), and psychosocial support (e.g., mental health services) for anyone affected by technology-related violence and abuse. The system also utilizes a documentation tool to record the testimonies of persons affected by online violence in Sri Lanka.[73]

Digital diplomacy for inclusive peace processes

Digital diplomacy offers significant potential to enhance inclusive peace processes in Sri Lanka by fostering collaboration, improving transparency, and countering misinformation. However, its adoption remains underutilized due to financial, policy, and leadership challenges, alongside a lack of established strategies and training.[74]

Successful examples, such as Ukraine's Donbas Dialogue, demonstrate how digital tools can connect stakeholders, identify shared concerns, and coordinate joint actions.[75] The United States Institute of Peace recommends similar approaches for Sri Lanka to improve access to information, encourage public participation, build coalitions and accountability.[76] Digital diplomacy in Sri Lanka could improve citizen access to information, increase government responsiveness to citizen concerns, and promote public participation in governance and diplomatic processes.

PEACETECH FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE

The Aragalaya highlighted both the promise and challenges of using technology for social justice in Sri Lanka. On July 9, 2022, activists made history by successfully demanding the resignation of the President and Prime Minister after months of protests.[77] Despite government-imposed curfews, fuel shortages, 14-hour power cuts, and other obstacles, an estimated 200,000 people participated, demonstrating the public’s unwavering desire for economic accountability and social change and justice.[78][79] The Aragalaya was groundbreaking in uniting Sri Lankans across ethnic and religious divisions that had historically separated them.[80] Technology played a critical role in these efforts, with apps, hashtags, and other digital tools enabling coordination and amplifying the call for change.[81]

Digital peace and dignity narratives for strategic communication

An effective approach to Peacetech for Social Justice is using digital peace and dignity narratives. The Cyber Guardians project by Search Sri Lanka exemplifies this, training youth to create social media content promoting pluralism and peaceful messaging.[82] The initiative emphasized the power of social media and the importance of internet privacy while equipping participants to counter hate speech, mis- and disinformation. A key component was its Digital Storytelling module, which encouraged creative strategies for spreading peaceful narratives.[83] Timely counter-messaging and multi-stakeholder collaboration are essential to fostering peace and dignity narratives and reducing harmful online content.

Digital social movements for shifting power

Digital social movements in Sri Lanka have played a significant role in driving change and spotlighting social issues. The Aragalaya exemplified this by leveraging social media campaigns, with hashtags like #GotaGoHome and #GotaGoGama to critique Gotabaya Rajapaksa's leadership and expose human rights abuses, and demanding his resignation from office. Protest art, including memes and GIFs, was widely shared to engage younger audiences and mobilize participation. Innovative tools such as livestreams, geolocation apps, and VPNs were crucial for documenting demonstrations, coordinating protests, and bypassing government censorship. Non-violent resistance strategies, combined with targeted information-sharing campaigns, helped engage a broader audience. Additionally, fuel-sharing apps facilitated carpooling to protest sites, reducing both transportation costs and the environmental impact of the protests. These efforts underscore the power of digital tools in amplifying voices and fostering social change.[84]

Digital witness, citizen journalism and human rights investigations

Digital witness, citizen journalism, and human rights investigations have become essential tools for promoting transparency and accountability, particularly in environments where traditional media is censored or biased.

Digital witness and livestreaming played a pivotal role during the Aragalaya, allowing activists to share real- time footage of events and amplify their calls for social justice. Digital peacebuilding strategies, such as digital witnessing through livestreaming and live tweeting, exposed systematic government repression and the violent force used against protesters, garnering both local and global attention.[85]

Citizen journalism has also gained traction in Sri Lanka as public trust in legacy media continues to erode due to perceived bias and close political ties.[86] While traditional media remains a primary information source for many, its credibility is increasingly questioned. This has opened the door for citizen journalists to fill the gap, offering alternative and, at times, more trustworthy narratives. The Center for Policy Alternatives hosts several initiatives: Maatram, Vikalpa and Groundviews. These have emerged as spaces for citizen journalists, although challenges around maintaining ethical standards persist.[87]

Digital fact-checking initiatives spearheaded by organizations such as Watchdog Sri Lanka, Hashtag Generation, and FactCheck LK by Verité Research have significantly bolstered the ecosystem of accountability and resilience to information disorder. These efforts gained prominence during the Aragalaya, playing a critical role in countering misinformation and propaganda. Hashtag Generation even developed a game, Dare to Know for Sri Lankans to build resilience against misinformation around the economic crisis, and make informed decisions about their future. By equipping the public with verified information, these initiatives empower citizens to develop informed opinions, thereby fostering transparency and promoting ethical standards in journalism.[88]

Challenges for digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka

Interviews and desk research for this study revealed the following challenges to digital peacebuilding.

DIGITAL DIVIDE

By 2021, more than half of Sri Lanka’s 22 million people had internet access, yet gender-based and urban-rural digital divides persist.[89] Infrastructure development in the Northern and Eastern provinces was delayed post- civil war, as funding for development was directed to urban areas, posing connectivity challenges in economically disadvantaged communities.[90] Furthermore, rural and up-country Tamil communities experience markedly lower levels of computer and digital literacy compared to urban populations, limiting the effectiveness of peacetech in bridging divides.[91][92] The COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis exacerbated these inequalities, highlighting disparities in access to digital technologies and education. With recent infrastructure investments, internet access has increased, and electricity blackouts became less frequent; however, the speed and quality of service is still inconsistent.[93] Improvements in infrastructure and digitization of various services, will be critical for advancing digital peacebuilding and fostering social and economic progress in Sri Lanka.[94]

LANGUAGE BARRIERS AND LACK OF CONTEXTUALIZATION TOOLS

Language barriers and a lack of contextualization in digital tools present significant obstacles to digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka, where Sinhalese, Tamil, and English are all used online. The absence of advanced content moderation tools for Sinhala and Tamil exacerbates the spread of hate speech and misinformation.[95] While global platforms like Meta, Google, and TikTok have policies for managing harmful content, these systems function most effectively in English. Consequently, hate speech in local languages often evades detection posing a challenge for digital peacebuilding.[96] The 2018 anti-Muslim riots underscore the consequences of these gaps as multilingual hate speech on social media fueled violence, prompting the government to block access to platforms like Facebook temporarily. While effective in curbing immediate harm, such measures are unsustainable, limiting access to vital information and communication.

With noteworthy developments in AI, various tools using natural language processing (NLP) have been developed in India and Sri Lanka to detect hate speech in Tamil. No equivalent tool yet addresses Sinhala, which is the most widely spoken language in the country. Sinhala is considered a lower-resource language, characterized by data scarcity and limited training datasets. This lack of resources hampers the ability to capture the full nuances and context of the language.[97] Without contextualized tools or local expertise, platforms struggle to detect nuances in speech, dialect, and imagery, enabling the persistence of harmful content.[98] In their research, Wijeratne and de Silva developed both a Sinhala language corpus and a list of stopwords tailored to the Sinhala language, which are essential for NLP applications. By providing a foundational dataset and tools for Sinhala, their work can facilitate the development of more sophisticated AI- driven content moderation systems that better understand the linguistic nuances unique to Sri Lanka, thereby enhancing digital peacebuilding efforts in Sri Lanka.[99]

Another challenge in content moderation is the lack of local staff at social media companies. Moderators often have limited knowledge of Sri Lanka's unique social-political dynamics, which complicates their ability to identify and address hate speech, especially on platforms like YouTube where content is primarily verbal. This shortfall can contribute to social unrest and conflict, as nuances in speech, dialect, and imagery are overlooked.[100]

VISUAL AND SYMBOLIC CONTENT

Hate speech, mis- and disinformation are increasingly visual, targeting younger demographics and complicating content moderation. In Sri Lanka, cartoons, GIFs, and memes have become popular communication methods. The rise of visual content increases the potential for misinformation spread, as algorithms often fail to track embedded information in images, focusing only on associated text. This poses a significant challenge for content moderation and fact-checking since visual content prompts quicker, emotional responses and is more memorable. Developing effective strategies to monitor and regulate visual content is crucial to combat misinformation and enhance accuracy and transparency in online communication.[101]

Furthermore, the construction and reinforcement of a new Sinhalese 'virtual' identity through visual media and images evokes shared values, interests, and experiences, strengthening this identity with symbols that foster pride and belonging, and sometimes employing racist rhetoric or idealistic memories of war. This emergent form of Sinhalese ethnicity on social media not only complicates efforts to regulate digital content with local symbols but also raises concerns about the exclusion of minority groups and potential ethnic tensions.[102]

PRIVACY AND SAFETY CONCERNS

Privacy, security and safety challenges remain critical for civil society organizations, journalists, and activists working to address online hate speech and misinformation, particularly when countering government narratives. The sensitive nature of peacebuilding requires robust safeguards against hacking, surveillance, and other threats, yet current measures remain inadequate.[103] Sri Lanka has experienced significant political shifts in the last few years, with each administration facing scrutiny over human rights practices and security policies. This environment has exacerbated obstacles for digital peacebuilding, online activism, and independent journalism, intensifying restrictions and fostering an atmosphere of intimidation and limited freedom of expression.[104]

Moderators have even faced risks of political backlash and security threats when addressing such content. [105] Internet freedom in Sri Lanka has remained constrained across presidential transitions, and increased harassment and intimidation of journalists and activists have led to self-censorship and a pervasive climate of fear. Arrests for online activity targeting individuals have further eroded free expression. Sri Lanka's low ranking on the World Press Freedom Index (150th in 2024), according to Reporters Without Borders, reflects these ongoing concerns.[106]

The previously mentioned Online Safety Act poses significant threats to privacy and complicates digital peacebuilding by granting broad powers to control and censor online content, often under vague definitions of prohibited material. This ambiguity can lead to arbitrary enforcement, potentially targeting political dissent and stifling democratic engagement. The lack of specific safeguards for vulnerable groups further undermines the Act's stated goals of protection, reducing public trust in digital platforms. The Act fosters an environment of fear and control, rather than safety and open dialogue, which can be detrimental to digital peacebuilding efforts.[107] However, the aforementioned Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) provides citizens some hope for improved privacy and security practices, empower individuals with more control over their data.[108]

FUNDING CONSTRAINTS, LACK OF CAPACITY AND COORDINATION

The effectiveness of digital peacebuilding efforts in Sri Lanka is hindered by funding shortages, limited technical expertise, and a lack of coordinated action among stakeholders. Civil society, government agencies, and other actors often struggle to leverage digital platforms for peacebuilding due to insufficient resources and skills, preventing the full potential of peacetech from being realized.

Duplication of efforts and a lack of collaboration exacerbate these challenges. For instance, organizations like IREX and Search for Common Ground have run similar digital media literacy programs but do not seem to coordinate.[109][110] While initiatives such as the UNDP Sri Lanka Community of Practice on online hate speech offer valuable platforms for likeminded organizations to share experiences, there is a lack of next steps and proper facilitation to collaborate effectively.[111]

There is a notable shortage of trainers and consultants specializing in the intersection of peace and technology in Sri Lanka, especially outside Colombo. As a result, some consultants lack the cultural context or linguistic proficiency necessary for effective engagement, while others lack the technical expertise required for digital peacebuilding.[112] Even trilingual trainers may have limited contextual understanding or technical skills in this field. Screening trainers before project deployment is essential to avoid issues related to gender sensitivity and negligence. Expanding capacity through training-of-trainer programs is crucial to increase the number of qualified professionals and prevent burnout among existing experts. While the government has supported training initiatives on issues such as HIV and sexual and reproductive health, digital peacebuilding and combating hate speech have yet to be prioritized as mainstream areas of focus.[113]

Smaller grassroots organizations contribute significantly but often lack the funding and resources available to larger entities. Coordination at district and regional levels is crucial to include these groups and amplify their efforts. However, recruiting participants for digital peacebuilding programs remains challenging, particularly in rural areas with limited technology access and network issues. Additionally, cultural hesitations among Muslim and Tamil families in the Northern and Eastern provinces often discourage young women from participating in workshops on hate speech despite their focus on promoting safe online engagement and digital literacy.[114]

Several interviewees observed that the same group of individuals tends to participate in digital peacebuilding trainings, often those who already agree with the content. Without revising outreach strategies, evaluation methods, and training formats, these initiatives risk only reaching those already in agreement. There is an urgent need to expand digital peacebuilding efforts beyond the “Colombo bubble” and reach underserved populations in more localized settings, particularly those outside traditional NGO networks.[115]

Many challenges outlined in this section are deeply rooted in the constraints of the project cycle itself. Monitoring and evaluation requirements often lead to fragmented and siloed thinking, prioritizing quantity over quality. Funding cycles further push organizations to focus on short-term outputs, such as delivering numerous workshops or training sessions within limited timeframes, rather than fostering sustainable solutions through multi-stakeholder partnerships. While some organizations collaborate on specific projects, consistent funding is critical to transforming these collaborations into long-term, sustainable and impactful programs.[116]

Opportunities and recommendations for digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka

Peacetech is offering transformative opportunities for Sri Lankans. Yet digital peacebuilding in Sri Lanka faces several challenges, including the digital divide, language barriers, limited capacity due to funding constraints, the complexity of visual content, the lack of contextualization of tools, and privacy and security concerns. Overcoming these challenges requires multi-stakeholder collaboration, including the government, civil society organizations, tech and social media companies, journalists, and other actors involved in digital peacebuilding.

Interviews and desk research for this study revealed the following recommendations:

To the Sri Lankan Government

1. Amend the Online Safety Act to meet international human rights standards, and engage a diverse group of stakeholders, including civil society, journalists, human rights advocates, and tech experts in its governance.

2. Strengthen press freedom by investigating human rights abuses and disappearances of journalists and activists and implementing robust protections for online press freedom.

3. Expand digital public infrastructure, especially in rural areas in the Northern and Eastern provinces, to enhance connectivity and improve equitable access to digital peacebuilding tools.

4. Develop digital archives for transitional justice: Collaborate with civil society to create digital archives documenting community experiences during the civil war to support transitional justice, aid in the preservation of collective memory, and facilitate reconciliation efforts.

5. Develop and use digital early warning systems for conflict in partnership with the UN OHCHR.

6. Leverage digital governance platforms: Use digital dialogue and deliberative technologies to promote transparency, enhance civic engagement, improve public trust in government, and foster collective solutions.

To civil society

1. Forge strategic partnerships and build a Digital Peacebuilding Community of Practice.

2. Develop and maintain a central database of peacetech and digital peacebuilding resources to support cross-sectoral partnerships and more sustainable efforts.

3. Promote digital literacy to build resilience to online harms and conflict: Partner with local journalists, news services, social media companies, and cybersecurity organizations to increase citizen knowledge on digital media, information disorder, and safety practices to build resilience to online harms and conflicts.

4. Strengthen online health and safety: Develop initiatives to address cyberbullying, digital addiction, and online harassment, emphasizing their role in reducing polarization and enhancing mental and emotional resilience.

5. Amplify marginalized voices: Support campaigns that promote intercommunal dialogue, address historical grievances, and foster reconciliation, emphasizing the engagement of marginalized communities.

6. Encourage digital truth-telling: Utilize storytelling platforms and citizen journalism to document untold stories and enhance understanding across diverse communities.

7. Leverage AI technologies to bridge language barriers for improved digital dialogue initiatives.

8. Engage the private sector: Work with social media and technology companies to harness private sector resources and innovations for peacebuilding.

9. Continue to advocate for policy change: Engage with the government to advocate for policies that support digital peacebuilding and safeguard human rights.

10. Foster multi-dimensional digital peacebuilding: Partner to create and implement digital peacebuilding programs that address economic, social, community, and educational needs comprehensively.

To funders

1. Promote local peacetech innovation: Invest in locally-led and locally-owned digital peacebuilding projects.

2. Support inclusivity in digital peacebuilding: Allocate funds to programs that meaningfully engage and support minorities, including religious and ethnic minorities, women, LGBTQIA+ communities, and youth to increase their representation in digital peacebuilding efforts.

3. Fund initiatives that incorporate peacebuilding principles in digital media literacy training: Support programs emphasize managing information disorder, fact-checking skills, and promote conflict resolution through dialogue skills.

4. Foster regional collaboration: Connect local organizations with international networks to enhance knowledge sharing and boost the effectiveness of peacebuilding programs.

5. Support holistic programs: Fund initiatives that address the root causes of poverty, conflict, and social exclusion. Focus on integrated approaches that enhance community resilience, promote peacebuilding, and support economic development.

To technology and social media companies

1. Localize and invest in content moderation: Hire and train local staff with cultural and linguistic expertise to enhance moderation processes. Collaborate with Sri Lankan civil society to improve moderator training, ensuring systems accommodate linguistic diversity and socio-political nuances with tailored tools and strategies.

2. Support digital dialogue efforts by improving NLP AI tools, such as Sinhala-Tamil translation systems, to bridge linguistic and ethnic divides online.

3. Develop tailored digital detection systems and early warning for conflict tools for safer digital spaces.

4. Strengthening partnerships with civil society for timely removal of harmful content (e.g. expand initiatives like Meta’s Trusted Partner program) and compensating organizations for this work.

5. Create or fund the peacetech innovation to help individuals and civil society prevent and mitigate online violence and the spread of harmful digital content.

6. Enhance cybersecurity awareness: Partner with civil society to train communities on cybersecurity practices and safeguarding against digital threats that lead to conflict.

To all stakeholders

1. Collaborate across civil society, tech companies, journalists, and government to co-create technology solutions that address conflict and promote sustainable peace.

By embracing innovation and leveraging peacetech, the peacebuilding community can strengthen resilience, adaptability, and interconnectedness, while forging new partnerships and collaborations in the pursuit of lasting, positive peace.

Acknowledgment

The author conducted the research as a Master of Global Affairs student and a Kroc Institute Fellow at the University of Notre Dame and benefited from generous financial and academic support from the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and the Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies.

NOTES

[1] Schirch, Lisa. “25 Spheres of Digital Peacebuilding and PeaceTech.” Toda Peace Institute, Sep 2020. https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-93_lisa-schirch.pdf. p.2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Stanford University. "Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam." Mapping Militant Organizations, Center for International Security and Cooperation, last modified June 2018, https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/liberation-tigers-tamil-elam.

[4] Human Rights Watch. “Sri Lanka: UN Report Describes Alarming Rights Situation.” Human Rights Watch, Mar 3, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/03/sri-lanka-un-report-describes-alarming-rights-situation.

[5] Mohammed, Nawaz, and Kelsey Hampton . “Opportunities for Peace and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka through Shared Values.” Search for Common Ground, June 2024. https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Opportunities-for-peace-and-reconciliation-in-Sri-Lanka-June-2024.pdf.

[6] Nozell, Melissa, and Jumaina Siddiqui. “Two Years after Easter Attacks, Sri Lanka’s Muslims Face Backlash.” United States Institute of Peace, Sep 17, 2021, www.usip.org/publications/2021/04/two-years-after-easter-attacks-sri-lankas-muslims-face-backlash.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Freedom House. “Sri Lanka: Freedom on the Net”. Freedom House, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/country/sri-lanka/freedom-net/2024

[9] OHCHR. “Sri Lanka: UN Human Rights Experts Condemn Repeated Use of Emergency Measures to Crackdown on Protests.” OHCHR, Aug 8, 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/08/sri-lanka-un-human-rights-experts-condemn-repeated-use-emergency-measures.

[10] Marsh, Nick. “Sri Lanka: The Divisions behind the Country's United Protests.” BBC News, May 3, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61295238.

[11] Mohammed, Nawaz, and Kelsey Hampton . “Opportunities for Peace and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka through Shared Values.” Search for Common Ground, June 2024. https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Opportunities-for- peace-and-reconciliation-in-Sri-Lanka-June-2024.pdf.

[12] Schirch, Lisa. “Social Media Impacts on Conflict Dynamics:” Policy Brief No. 73, Toda Peace Institute, May 2020, toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-22_lisa-schirch_social-media-impacts.pdf, p. 10.

[13] (Respondent 5)

[14] Banadaranaike, Anisha Dias et al. “Information Disorder and Mainstream Media in Sri Lanka: A Case Study”. Media Team of Verité Research. 2020 https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/VR_Eng_RR_May2021_Information-Disorder-and-Mainstream-Media-in-Sri-Lanka-A-Case-Study.pdf

[15] Freedom House. “Sri Lanka: Freedom on the Net”. Freedom House, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/country/sri-lanka/freedom-net/2024

[16] Nozell, Melissa, and Jumaina Siddiqui. “Two Years after Easter Attacks, Sri Lanka’s Muslims Face Backlash.” United States Institute of Peace, Sep 17, 2021, www.usip.org/publications/2021/04/two-years-after-easter-attacks-sri-lankas-muslims-face-backlash.

[17] (Respondent 2, 5, 8)

[18] (Respondent 5 and 11)

[19] (Respondent 5)

[20] Biedermann, Roxane. “Hashtag Generation’s Social Media Analysis Finds That Online Abuse Is Booming during the Sri Lankan Crisis.” Media Diversity Institute, Oct 17 2022, www.media-diversity .org/hashtag-generations-social-media-analy sis-finds-that-online-abuse-is-booming-during-the-sri-lankan-crisis/; Ibrahim, Zainab and Sachini Perera. "Making Delete Nothing: Making a Feminist Internet." SSA Lanka, Nov 22, 2020, ssalanka.org/making-delete-nothing-making-feminist-internet-zainab-ibrahim-sachini-perera/.

[21] (Respondents 3, 8, 14, and 16)

[22] Perera, S. & Ibrahim, Z. 2021. “Somewhere Only We Know: Gender, sexualities, and sexual behaviour on the internet in Sri Lanka”. Association for Progressive Communications. https://erotics.apc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Somewhere-only-We-Know-Online.pdf . p. 11.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] (Respondent 8, 16)

[26] Hattotuwa, Sanjana, and Shilpa Samaratunge. “Liking Violence - A Study of Hate Speech on Facebook in Sri Lanka.” CPA Lanka, Sep 2014, www.cpalanka.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Hate-Speech-Executive-Summary.pdf.

[27] United Nations DPPA, and Centre for Humane Dialogue. “Digital Mediation Toolkit 2019.” United Nations Peacemaker, Mar 2019, https://www.hdcentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Digital-Technologies-and-Mediation-in-Armed-Conflict.pdf

[28] Rezwan. “Social Media Platforms in Sri Lanka Briefly Restricted amidst Curfew and Protests.” Global Voices, May 11, 2022, globalvoices.org/2022/04/04/social-media-platforms-in-sri-lanka-briefly-restricted-amidst-curfew-and-protests/.

[29] Deutsche Welle. “Sri Lanka Restricts Access to Social Media amid Protests.” Deutsche Welle, Apr 3, 2022, www.dw.com/en/sri-lanka-restricts-access-to-social-media-platforms-amid-protests/a-61343824.

[30] Biedermann, Roxane. “Hashtag Generation’s Social Media Analysis Finds That Online Abuse Is Booming during the Sri Lankan Crisis.” Media Diversity Institute, Oct 17, 2022, www.media-diversity.org/hashtag-generations-social-media-analysis-finds-that-online-abuse-is-booming-during-the-sri-lankan-crisis/.

[31] Wong and Paul. “Sri Lanka’s Social Media Blackout Reflects Sense That Online Dangers Outweigh Benefits.” The Guardian, Apr 22, 2019, www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/22/sri-lankas-social-media-blackout-reflects-sense-that- online-dangers-outweigh-benefits.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Kofi Annan Foundation. “Three Perspectives on Ethics-Driven Digital Peacebuilding.” Kofi Annan Foundation, Dec 9, 2022, www.kofiannanfoundation.org/peace-and-trust/3-perspectives-on-ethics-driven-peacebuilding/.

[34] (Respondent 2, 5)

[35] Human Rights Watch. “If We Raise Our Voice They Arrest Us.” Human Rights Watch, September 17, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/09/18/if-we-raise-our-voice-they-arrest-us/sri-lankas-proposed-truth-and-reconciliation.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Digital Blooms: Social Media and Violence in Sri Lanka.” Policy Brief 28. Toda Peace Institute, Nov 2018, https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-28_sanjana-hattotuwa_digital-blooms-social-media-and-violence-in-sri-lanka.pdf.

[38] Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. “2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - Sri Lanka.” U.S. Department of State, 2023. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/sri-lanka/.

[39] Amnesty International. “Increased Marginalization, Discrimination and Targeting of Sri Lanka’s Muslim Community.” Amnesty International, March 19, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ASA3738662021ENGLISH.pdf; Human Rights Watch. “Sri Lanka: Minorities, Activists Targeted.” Human Rights Watch, February 10, 2022. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/01/13/sri-lanka-minorities-activists-targeted. Human Rights Watch. “Sri Lanka: False Terrorism Cases Enable Repression.” Human Rights Watch, July 18, 2024. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/07/17/sri-lanka-false-terrorism-cases-enable-repression.

[40] (Respondents 5, 11, and 22)

[41] Sri Lanka Brief. “A New Law to Regulate Social Media in Sri Lanka: A Response.” Sri Lanka Brief, Mar 2, 2023, srilankabrief.org/a-new-law-to-regulate-social-media-in-sri-lanka-a-response/.

[42] Jayasinghe, Uditha. “Sri Lanka Passes New Law to Regulate Online Content | Reuters.” Reuters, Jan 24, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/sri-lanka-votes-new-law-regulate-online-content-2024-01-24/.

[43] AccessNow. “No Liberty, No Safety: Sri Lanka Must Withdraw the Online Safety Bill.” Access Now, Feb 1, 2024. https://www.accessnow.org/press-release/sri-lanka-must-withdraw-the-online-safety-bill/.

[44] Centre for Communication Governance at National Law University Delhi, LIRNEasia and BRAC University, and Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. “Social Media Regulation and the Rule of Law: Key Trends in Sri Lanka, India and Bangladesh.” EngageMedia, Sep 30, 2024. https://engagemedia.org/2024/social-media-regulation-report/.

[45] EconomyNext. “Sri Lanka Online Safety Act Amendment Bill Published.” EconomyNext, Aug 21, 2024. https://economynext.com/sri-lanka-online-safety-act-amendment-bill-published-177446/.

[46] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. Sri Lanka’s Online Safety act: The government’s lies, falsehoods, & deception, April 23, 2024. https://sanjanah.wordpress.com/2024/04/23/sri-lankas-online-safety-act-osa-the-governments-lies-falsehoods-deception/.

[47] Amnesty International. “Sri Lanka: Online Safety Act Major Blow to Freedom of Expression.” Amnesty International, January 31, 2024. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/01/sri-lanka-online-safety-act-major-blow-to-freedom-of-expression/.

[48] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Amending the Online Safety Act and the Centrality of Human Rights Principles.” Groundviews, Nov 7, 2024. https://groundviews.org/2024/11/07/amending-the-online-safety-act-and-the-centrality-of-human-rights-principles/.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. Sri Lanka’s Online Safety Act: The government’s lies, falsehoods, & deception, April 23, 2024. https://sanjanah.wordpress.com/2024/04/23/sri-lankas-online-safety-act-osa-the-governments-lies-falsehoods-deception/.

[51] (Respondent 10)

[52] Search for Common Ground Sri Lanka “Recent Projects.” Search for Common Ground, n.d., https://www.sfcg.org/asia/sri-lanka/

[53] (Respondent 10)

[54] Search for Common Ground Sri Lanka “Recent Projects.” Search for Common Ground, n.d., https://www.sfcg.org/asia/sri-lanka/

[55] (Respondent 15); DreamSpace Academy. “Peacebuilding & Reconciliation Programmes.” DreamSpace Academy. https://dreamspace.academy/pages/4-1-0-peacebuilding.php.

[56] (Respondent 22)

[57] President’s Office Sri Lanka. “Accelerating Digital Transformation to Drive Economic Growth.” News LK, October 29, 2024. https://www.news.lk/news/political-current-affairs/item/37561-accelerating-digital-transformation-to-drive-economic-growth.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Parliament of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. “Personal Data Protection Act, no. 9 of 2022,” March 19, 2022. https://www.parliament.lk/uploads/acts/gbills/english/6242.pdf.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Narimatsu, Junko, Aneesa Mendis, and Jagath Seneviratna. “Digitalization Is the Way Forward for Sri Lanka.” World Bank Blogs, May 17, 2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/endpovertyinsouthasia/digitalization-way-forward-sri-lanka.

[62] Search for Common Ground. “We-gital heroes: Youth in digital peacebuilding.” Aug 29, 2020. https://www.sfcg.org/project/we-gital-heroes-youth-in-digital-peacebuilding/

[63] (Respondents 26 and 27)

[64] Media Diversity Institute. “Get the trolls out: Sri Lanka.” Media Diversity Institute, Jan 22, 2021, https://www.media-diversity.org/projects/get-the-trolls-out-sri-lanka/.

[65] IREX Sri Lanka. “Catalyzing the Media's Digital Transformation in Sri Lanka.” Media Empowerment for a Democratic Sri Lanka (MEND), IREX, Sep 21, 2021. https://www.irex.org/success-story/catalyzing-medias-digital-transformation-sri-lanka.

[66] (Respondent 28).

[67] Salvini, Renata. “Sri Lankan Youth Take on Media Literacy Ambassador Roles Following Workshops.” International Journalists’ Network, Oct 22, 2024. https://ijnet.org/en/story/sri-lankan-youth-take-media-literacy-ambassador-roles-following-workshops.

[68] Palihapitiya, Madhawa. "Early Warning, Early Response: Lessons from Sri Lanka." Building Peace Forum, Sep 24, 2013, buildingpeaceforum.com/2013/09/early-warning-early-response-lessons-from-sri-lanka/.

[69] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “The End of War in Sri Lanka, Captured for Posterity by Google Earth.” Groundviews, November 3, 2021. https://groundviews.org/2012/09/12/the-end-of-war-in-sri-lanka-captured-for-posterity-by-google-earth/.

[70] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Sri Lanka’s Forgotten Mass Graves: Google Earth and Remembering the Dead in Nandikadal.” Groundviews, November 3, 2021. https://groundviews.org/2012/09/18/sri-lankas-forgotten-mass-graves-google-earth-and-remembering-the-dead-in-nandikadal/.

[71] (Respondents 26 and 27).

[72] Delete Nothing. “Delete Nothing and Hashtag Generation Launch ‘Prathya.” Delete Nothing, Mar 16, 2023, https://deletenothing.org/delete-nothing-and-hashtag-generation-launch-prathya

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ranaweera, K., Wibisono, MSc, P., & Pramono, B. Effect of Digital Diplomacy in International Relations: Lessons for Sri Lanka to Mitigate Negative Coverage of Security and Human Rights Situations After 2009. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, 2023, 37(1), 325-332. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.52155/ijpsat.v37.1.5062

[75] Schirch, Lisa. “25 Spheres of Digital Peacebuilding and PeaceTech.” Policy Brief No. 93, Toda Peace Institute, Sep 2020. https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-93_lisa-schirch.pdf. p. 22.

[76] Hirblinger, Andreas T. “Digital Inclusion in Mediated Peace Processes: How Technology Can Enhance Public Participation”, Peace Works, United States Institute of Peace, Sep 2020, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/20200929-pw_168-digital_inclusion_in_mediated_peace_processes_how_technology_can_enhance_participation-pw.pdf.

[77] Wright, George. “Sri Lanka: President Rajapaksa to Resign after Palace Stormed.” BBC News, Jul 10, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62108597.

[78] Jayasinghe, Uditha. “Sri Lanka Stops Fuel Supply to Non-Essential Services as Crisis Worsens.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, Jun 27, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/crisis-hit-sri-lanka-shuts-schools-urges-work-home-save-fuel-2022-06-27/.

[79] OHCHR. “Sri Lanka: UN Human Rights Experts Condemn Repeated Use of Emergency Measures to Crackdown on Protests.” OHCHR, Aug 8, 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/08/sri-lanka-un-human-rights-experts-condemn-repeated-use-emergency-measures.

[80] Marsh, Nick. “Sri Lanka: The Divisions behind the Country's United Protests.” BBC News, May 3, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61295238.

[81] (Respondent 5).

[82] (Respondent 10).

[83] Search for Common Ground. “Sri Lanka Cyber Guardians Program Final Evaluation Report”, May 2020, www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SFCG-Sri_Lanka_Cyber_Guardians_Final_Evaluation_2020.pdf

[84] (Respondents 2, 5, 11, 23)

[85] (Respondents 5 and 11).

[86] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Digital Blooms in Social Media and Violence.” Social Media Impacts on Conflict and Democracy, edited by Lisa Schirch, Routledge, 2021, p. 183.

[87] (Respondent 1, 17, 23, 25)

[88] (Respondents 23, 25, 26, and 27).

[89] Factum LK. “Adopting a Code of Practice for Global Social Media Concerning Sri Lanka-Related Content.” SafewebLK, 2022, factum.lk/safeweblk/.

[90] Freedom House. “Sri Lanka: Freedom on the Net”. Freedom House, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/country/sri-lanka/freedom-net/2024

[91] Ibid.

[92] (Respondents 8, 13, 14)

[93] Freedom House. “Sri Lanka: Freedom on the Net”. Freedom House, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/country/sri-lanka/freedom-net/2024

[94] Ibid.

[95] Perera, W. and S. Ahangama "Hate Speech Detection on Sinhala Social Media Text Using LSTM and FastText." Open University of Sri Lanka Research Sessions 2021, Open University of Sri Lanka, 2021, https://ours.ou.ac.lk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ID-174_HATE-SPEECH-DETECTION-ON-SINHALA-SOCIAL-MEDIA-TEXT-USING-LSTM-AND-FASTTEXT.pdf.

[96] Wijeratne, Yudhanjaya. "Facebook, Language, and the Difficulty of Moderating Hate Speech." Media@LSE Blog, London School of Economics and Political Science, Jul 23 2020, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/medialse/2020/07/23/facebook-language-and-the-difficulty-of-moderating-hate-speech/.

[97] Sathya, Krithik M. et al. “Sinhala and Gujarati Hate Speech Detection.” CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Vol 3681. ISSN 1613-0073. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3681/T6-18.pdf

[98] (Respondent 8).

[99] Wijeratne, and de Silva. “Sinhala Language Corpora and Stopwords from a Decade of Sri Lankan Facebook.” LIRNEasia, July 2020. https://lirneasia.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Facebook_Sinhala_main_corpus_fixed.pdf.

[100] (Respondent 8, 20, and 22).

[101] (Respondent 20).

[102] Hasangani, Sandunika. “Virtual Ethnicity? The Visual Construction of 'Sinhalaness' on social media in Sri Lanka.” South Asia, vol. 45, no. 3, 2022, p. 417–39, https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2021.1972551.

[103] (Respondents 5, 11, 23)

[104] Freedom House. “Sri Lanka: Freedom on the Net 2024.” Freedom House, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/country/sri-lanka/freedom-net/2024

[105] (Respondents 5 and 11).

[106] UCA News. “New Sri Lankan president urged to repeal draconian laws.” Oct 1, 2024, https://www.ucanews.com/news/new-sri-lankan-president-urged-to-repeal-draconian-laws/106568

[107] Hattotuwa, Sanjana. Sri Lanka’s Online Safety act: The government’s lies, falsehoods, & deception, April 23, 2024. https://sanjanah.wordpress.com/2024/04/23/sri-lankas-online-safety-act-osa-the-governments-lies-falsehoods-deception/.

[108] Parliament of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Personal Data Protection Act, no. 9 of 2022, March 19, 2022. https://www.parliament.lk/uploads/acts/gbills/english/6242.pdf.

[109] IREX Sri Lanka. “Catalyzing the Media's Digital Transformation in Sri Lanka.” Media Empowerment for a Democratic Sri Lanka, IREX, Sep 21, 2021. https://www.irex.org/success-story/catalyzing-medias-digital-transformation-sri-lanka.

[110] (Respondents 10 and 28).

[111] (Respondent 10).

[112] (Respondents 8 and 16).

[113] (Respondent 8).

[114] (Respondents 8, 14, 16).

[115] (Respondent 3, 8, 13).

[116] (Respondent 2, 10, 28).

WORKS CITED

AccessNow “No Liberty, No Safety: Sri Lanka Must Withdraw the Online Safety Bill.” Access Now, Feb 1, 2024. https://www.accessnow.org/press-release/sri-lanka-must-withdraw-the-online-safety-bill/.

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) “High-Resolution Satellite Imagery and the Conflict in Sri Lanka.” Geotech, AAAS, 2009. https://www.aaas.org/resources/geotech/high-resolution-satellite-imagery-and-conflict-sri-lanka.

Amnesty International. “Increased Marginalization, Discrimination and Targeting of Sri Lanka’s Muslim Community.” Amnesty International, March 19, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ASA3738662021ENGLISH.pdf.

Amnesty International. “Sri Lanka: Online Safety Act Major Blow to Freedom of Expression.” Amnesty International, January 31, 2024. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/01/sri-lanka-online-safety-act-major-blow-to-freedom-of- expression/.

Banadaranaike, Anisha Dias et al. “Information Disorder and Mainstream Media in Sri Lanka: A Case Study”. Verité Research. May 2021, https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/VR_Eng_RR_May2021_Information-Disorder-and-Mainstream-Media-in-Sri-Lanka-A-Case-Study.pdf

Biedermann, Roxane. “Hashtag Generation’s Social Media Analysis Finds That Online Abuse Is Booming during the Sri Lankan Crisis.” Media Diversity Institute, Oct 17, 2022, www.media-diversity.org/hashtag-generations-social-media- analysis-finds-that-online-abuse-is-booming-during-the-sri-lankan-crisis/.

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. “2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - Sri Lanka.” U.S. Department of State, 2023. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/sri-lanka/.

Centre for Communication Governance at National Law University Delhi, LIRNEasia and BRAC University , and Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. “Social Media Regulation and the Rule of Law: Key Trends in Sri Lanka, India and Bangladesh.” EngageMedia, September 30, 2024. https://engagemedia.org/2024/social-media-regulation-report/.

De Silva, Sam. “Leveraging Technology for Social Change in Sri Lanka - Information Saves Lives.” Internews, February 23, 2021. https://internews.org/story/leveraging-technology-social-change-sri-lanka/.

Deane, Ruqyyaha. “Together They Protest, Together They Break Fast.” Print Edition - The Sunday Times, Sri Lanka, May 1, 2022, www.sundaytimes.lk/220501/plus/together-they -protest-together-they-break-fast-481109.html.

Delete Nothing. “Delete Nothing and Hashtag Generation Launch ‘Prathya.” Delete Nothing, 16 Mar 17 2023, https://deletenothing.org/delete-nothing-and-hashtag-generation-launch-prathya

Democracy Reporting International. “Regulating Social Media in Sri Lanka,” Democracy Reporting International, Mar 2021, democracyreporting.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/images/3635DRI_Regulating%20Social%20Media%20in%20Sri%20Lanka_Report_Revised%20March%202021.pdf.

Deutsche Welle. “Sri Lanka Restricts Access to Social Media amid Protests.” Deutsche Welle, Apr 3, 2022, www.dw.com/en/sri-lanka-restricts-access-to-social-media-platforms-amid-protests/a-61343824.

Digital Wellbeing Initiative. "The Digital Wellbeing Initiative: About Us”, Digital Wellbeing Initiative, n.d., thedwi.org/about-us/.

DreamSpace Academy. “Peacebuilding & Reconciliation Programmes.” DreamSpace Academy, n.d., https://dreamspace.academy/pages/4-1-0-peacebuilding.php.

Duursma, Allard, and John Karlsrud. “Technologies of Peace.” In The Oxford Handbook of Peacebuilding, Statebuilding, and Peace Formation, edited by Oliver P. Richmond and Gëzim Visoka, Oxford Academic, Jun 9, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190904418.013.28.

Factum LK. “Adopting a Code of Practice for Global Social Media Concerning Sri Lanka-Related Content.” SafewebLK, 2022, factum.lk/safeweblk/.

Firchow, Pamina, Charles Martin-Shields, Atalia Omer, and Roger Mac Ginty. “PeaceTech: The Liminal Spaces of Digital Technology in Peacebuilding.” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 1, Feb 2017: 4–42. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1093/isp/ekw007.

Freedom House. “Sri Lanka: Freedom on the Net 2024.” Freedom House, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/country/sri-lanka/freedom-net/2024

Galtung, Johan. “An Editorial.” Journal of Peace Research, vol. 1, no. 1, 1964, pp. 1-4.

Groundviews. “Sri Lanka: The Evolution of the GOTAGOGAMA Protest Site and Its Periphery, in Photos Online.” Scribd, Jul 27 2022, https://www.scribd.com/article/584599967/Sri-Lanka-The-Evolution-Of-The-Gotagogama-Protest-Site-And-Its-Periphery-In-Photos.

Harris, et al. “Community Stewards and Social Cohesion in Digital Spaces.” ConnexUs, Feb 14, 2023, cnxus.org/resource/community-stewards-and-social-cohesion-in-digital-spaces/.

Hasangani, Sandunika. “Religious Identification on Facebook Visuals and (Online) Out-Group Intolerance: Experimenting the Sri Lankan Case.” Journal of Asian and African Studies (Leiden), vol. 57, no. 2, 2022, pp. 247–68, https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211008466.

Hasangani, Sandunika. “Virtual Ethnicity? The Visual Construction of ‘Sinhalaness’ on Social Media in Sri Lanka.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 45 (3): pp. 417–39, 2021. doi:10.1080/00856401.2021.1972551.

Hasangani, Sandunika. “Social Media and Visual/Textual Framing of Ethnic Stereotypes: The Virtual Construction of Muslim Image in Post-War Sri Lanka.” Journal of Asian and African Studies, no. 97, Mar 2019, https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/152029088399109094.

Hashtag Generation. “Fact Check.” Hashtag Generation, n.d., https://hashtaggeneration.org/fact-check/.

Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Sri Lanka’s Forgotten Mass Graves: Google Earth and Remembering the Dead in Nandikadal.” Groundviews, November 3, 2021. https://groundviews.org/2012/09/18/sri-lankas-forgotten-mass-graves-google-earth-and-remembering-the-dead-in-nandikadal/.

Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “The End of War in Sri Lanka, Captured for Posterity by Google Earth.” Groundviews, November 3, 2021. https://groundviews.org/2012/09/12/the-end-of-war-in-sri-lanka-captured-for-posterity-by-google-earth/.

Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Amending the Online Safety Act and the Centrality of Human Rights Principles.” Groundviews, Nov 7, 2024. https://groundviews.org/2024/11/07/amending-the-online-safety-act-and-the-centrality-of-human-rights-principles/.

Hattotuwa, Sanjana. Sri Lanka’s Online Safety act: The government’s lies, falsehoods, & deception, April 23, 2024. https://sanjanah.wordpress.com/2024/04/23/sri-lankas-online-safety-act-osa-the-governments-lies-falsehoods-deception/.

Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Digital Blooms: Social Media and Violence in Sri Lanka.” Policy Brief 28. Toda Peace Institute, Nov 2018, https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-28_sanjana-hattotuwa_digital-blooms-social-media-and-violence-in-sri-lanka.pdf.

Hattotuwa, Sanjana. “Digital Blooms in Social Media and Violence.” Social Media Impacts on Conflict and Democracy, edited by Lisa Schirch, Routledge, 2021, p. 182–93.

Hattotuwa, Sanjana, and Shilpa Samaratunge. “Liking Violence - A Study of Hate Speech on Facebook in Sri Lanka.” CPA Lanka, Sep 2014, www.cpalanka.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Hate-Speech-Executive-Summary.pdf.

Hirblinger, Andreas T. “Digital Inclusion in Mediated Peace Processes: How Technology Can Enhance Public Participation”, Peace Works, United States Institute of Peace, Sep 2020, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/20200929-pw_168-digital_inclusion_in_mediated_peace_processes_how_technology_can_enhance_participation-pw.pdf.

Hirblinger, Andreas T., et al. "Digital Peacebuilding: A Framework for Critical-Reflexive Engagement." International Studies Perspectives, 2022, https://doi-org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1093/isp/ekac015.

Human Rights Watch. “Sri Lanka: UN Report Describes Alarming Rights Situation.” Human Rights Warch, Mar 3, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/03/sri-lanka-un-report-describes-alarming-rights-situation.

Human Rights Watch. “If We Raise Our Voice They Arrest Us.” Human Rights Watch, September 17, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/09/18/if-we-raise-our-voice-they-arrest-us/sri-lankas-proposed-truth-and-reconciliation.

Human Rights Watch. “Sri Lanka: Minorities, Activists Targeted.” Human Rights Watch, February 10, 2022. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/01/13/sri-lanka-minorities-activists-targeted.

Human Rights Watch. “Sri Lanka: False Terrorism Cases Enable Repression.” Human Rights Watch, July 18, 2024. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/07/17/sri-lanka-false-terrorism-cases-enable-repression.

Ibrahim, Zainab and Sachini Perera. "Making Delete Nothing: Making a Feminist Internet." Social Scientist Association, Nov 22, 2020, ssalanka.org/making-delete-nothing-making-feminist-internet-zainab-ibrahim-sachini-perera/.

Information and Communication Technology Agency (ICTA) “National Digital Strategy 2030.” Information and Communication Technology Agency ICTA of Sri Lanka, May 2023. https://www.icta.lk/icta-assets/uploads/2023/05/Annex-1-National-Digital-Strategy-2030.pdf.

IREX Sri Lanka. “Catalyzing the Media's Digital Transformation in Sri Lanka.” Media Empowerment for a Democratic Sri Lanka (MEND), IREX, Sep 21, 2021. https://www.irex.org/success-story/catalyzing-medias-digital-transformation-sri-lanka.

Jayasinghe, Uditha. “Sri Lanka Passes New Law to Regulate Online Content | Reuters.” Reuters, January 24, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/sri-lanka-votes-new-law-regulate-online-content-2024-01-24/.

Jayasinghe, Uditha. “Sri Lanka Stops Fuel Supply to Non-Essential Services as Crisis Worsens.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, Jun 27, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/crisis-hit-sri-lanka-shuts-schools-urges-work-home-save-fuel-2022-06-27/.

Jayasinghe, Uditha, and Devjyot Ghoshal. “How a Band of Activists Helped Bring down Sri Lanka's Government.” Thomson Reuters, Jul 12, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/how-band-activists-helped-bring-down-sri-lankas-government-2022-07-11/.

Kofi Annan Foundation. “Three Perspectives on Ethics-Driven Digital Peacebuilding.” Kofi Annan Foundation, Dec 9, 2022, www.kofiannanfoundation.org/peace-and-trust/3-perspectives-on-ethics-driven-peacebuilding/.

Larrauri, Helena Puig and Anne Kahl. “Technology for Peacebuilding.” Stability International Journal of Security and Development, (Norfolk, VA), vol. 2, no. 3, Nov 22, 2013, Art. 61, https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.cv.

Larrauri, Helena Puig, and Olivier Cottray. “Technology at the Service of Peace.” SIPRI, Apr. 26, 2017, www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2017/technology-service-peace.

Lederach, John Paul. The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Lederach, John Paul. Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. United States Institute of Peace Press, 1997.

Marsh, Nick. “Sri Lanka: The Divisions behind the Country's United Protests.” BBC News, May 3, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61295238.

Media Diversity Institute. “Get the trolls out: Sri Lanka.” Media Diversity Institute, Jan 22, 2021, https://www.media-diversity.org/projects/get-the-trolls-out-sri-lanka/.

Mohammed, Nawaz, and Kelsey Hampton. “Opportunities for Peace and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka through Shared Values.” Search for Common Ground, June 2024. https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Opportunities-for-peace-and-reconciliation-in-Sri-Lanka-June-2024.pdf.

Narimatsu, Junko, Aneesa Mendis, and Jagath Seneviratna. “Digitalization Is the Way Forward for Sri Lanka.” World Bank Blogs, May 17, 2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/endpovertyinsouthasia/digitalization-way-forward-sri-lanka.

Nozell, Melissa, and Jumaina Siddiqui. “Two Years after Easter Attacks, Sri Lanka’s Muslims Face Backlash.” United States Institute of Peace, Sep 17, 2021, www.usip.org/publications/2021/04/two-years-after-easter-attacks-sri-lankas-muslims-face-backlash.

OHCHR. “Sri Lanka: UN Human Rights Experts Condemn Repeated Use of Emergency Measures to Crackdown on Protests.” OHCHR, Aug 8, 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/08/sri-lanka-un-human-rights-experts-condemn-repeated-use-emergency-measures.