Global Challenges to Democracy Report No.210

The Beautification of 21st Century Wars

John Keane and Almantas Samalavičius

February 20, 2025

Abstract

In this interview, John Keane argues that the public beautification of war is among the oddest features of the terrible meta wars of our century. With the help of communications media, war becomes an elaborately staged, picturesque tableau designed to transfix audiences and wall them off from war’s horrors. Savagery and ghastliness are no more. War becomes bloodless. It undergoes a form of beautification more subtle and more insidious than ever happened in the era of radio, film, and television. However, a new type of rebel journalism does something that is powerfully different. It does more than problematize meta wars by chipping away at their beautification. The new rebel journalism keeps alive and nurtures political hopes for an end to war.

Contents

Almantas Samalavičius (AS): You insist that the nature of war has dramatically, even fundamentally changed, and that this shift has been strongly influenced by so-called technological progress - a defining feature of modern life. Moreover, you argue that the wars of our period no longer bear any resemblance to last century‘s "radio" and "television" wars, as Marshall McLuhan labelled them. You say they are fundamentally different from those wars. McLuhan as well as other members of the Toronto School claimed that neither media nor other forms of technology are neutral and in this respect they largely differed from mainstream media research. Even if some of their observations are outdated because of new realities, what do you think of the Toronto School‘s insights for understanding how technology restructures our lives? How do digital technologies determine the nature and character of contemporary wars? *

* This interview is also published in Lithuanian in Kultūros barai 2 (February 2025), pp. 22-29.

John Keane (JK): My thinking focuses on the powerful role played by communications technologies in shaping the form and substance of war. In matters of war, runs my framing idea, we are living in a strange world unknown to our grandparents and great grandparents, a world immeasurably different from both the Cold War of the 20th century and recent talk by Niall Ferguson and other scholars of “Cold War II”. We’ve entered the age of destructive wars in which digital communications technologies are enabling not only frightening transformations of the modes and weapons of warfare – zero space-time coordination of armies, Hellfire precision-guided, air-to-ground missiles, and sophisticated cyber weapons capable of jamming and seizing control of enemy satellites – but also, paradoxically, media representations of war by governments, military PR propagandists, breaking news journalists, and soldiers and citizens that “gamify” war, beautify its horrors, and lullaby millions of people into nonchalance about wars that are seemingly emptied of blood, cruelty, and genocidal destruction.

The central point of this unorthodox interpretation is to highlight the way texts, sounds, and images are produced and circulated during wartime is of foundational importance in understanding wars past and present. I studied in Toronto, where Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan and others taught us that media of communication aren’t just add-on features of any given society, or to be understood as timeless “neutral” channels that convey ‘information’. They emphasized how different historical modes of communication differently structure people’s bodily senses, their mobility, patterns of cognition, mental horizons, and daily spacetime experiences of the world, even shaping the conduct and interpretation of war.

Radiobalilla, the first Italian mass-produced

radio set, 1937. Source: Wikicommons

Please let me mention some examples. Think of times defined mainly by oral communication when news and rumours of war were conveyed by word of mouth and written messages carried by foot runners, horses, donkeys, and camels. Information about battles, sieges, victories, and defeats was reported only after the fact. War did not know instant media coverage. Now think of the electrification and time-space shrinkage of war reportage and the beginnings of mass broadcasting of war. This first happened in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. The reshaping of the conduct and public experience of war by the application of radio, and then film and television technologies, was a defining feature of the 20th century. Electronically mediated messaging within the ranks of whole armies was normalized. By conquering illiteracy, distance and time lags, radio paved the way to the mass broadcasting of government propaganda to large audiences captivated by the weirdness of strange voices entering the home, factories and offices, bars and restaurants, and public squares. Just as FDR enchanted mass audiences and prepared them for war by means of his pioneering radio fireside chats, so shortly after his first radio speech in 1925 the thunderous voice of the former journalist and newspaperman Mussolini helped spread the spirit of ‘each village and school must have a radio’ fascist militarism through the airwaves of Italy, the country where radio broadcasting evolved under a totalitarian government to become a source of fascist entertainment, as in the broadcasting from Berlin of the 1936 Olympics, and an instrument of battle, for instance during the invasion of Ethiopia.

Marshall McLuhan accurately remarked that just as the Second World War was a radio war, the Vietnam War was the first television war. In his War and Peace in the Global Village (1968) he noted the historic significance of the way journalists for the first time used portable, battery-powered video tape “portopac” cameras and filed filmed dispatches by jet aircraft overnight to supply television outlets news for the next morning’s broadcasts at home. His point was not only that war had been rendered highly visible and its butchery made more emotionally palpable – that war had drawn closer to people’s lives and clawed at their senses as immediately ‘as the smell of a cigarette’. McLuhan invited us to remember the key historical point: in any age, in matters of war, the reigning forces and relations of communication structure how war is prosecuted, how war is reported, why this or that war is deemed significant, and how it “feels” to victims and witnesses alike. On the battlefield and in the living room, the medium shapes the sent messages – and the public reception of those messages.

McLuhan’s emphasis on the shaping power of communication infrastructures was soon to be confirmed by the advent (during the late 1960s) of satellite broadcasting which he predicted would wipe out time-space differences and promote a sense of “all-at-onceness” among audiences huddled around television sets at various points on our planet. McLuhan did not live to experience the communications revolution to come: the shift to digital technologies that would have transformative effects on the modus operandi of armies and their weapons of war and immerse audiences in a strange new world of digitally integrated newspapers, radio, and television, the multiplication of gatekeeper and gate watcher media platforms, a satellite/fibre optic/wi-fi- linked world in which war is mediated by PCs, laptops, smartphones, cameras, podcasts, search engines, audio books, chatbots, video games, livestreamed music, digital marketing, instant messaging, cloud storage, and audio-visual conferencing tools such as Webex, Zoom, and China’s Voov.

AS: Despite the fact that the attrocities of the war are sensationally reported, they are seldom accompanied by realistic images of what mutilated dead bodies as well as the grief of the victims of war really look like. You seem to imply that digital media provides a kind of aestheticized version of the unspeakable horrors and brutalities of war. What are the social and cultural consequences of this “beautification“?

JK: It has long been said that war is hell on earth. When war begins, the devil opens hell, runs an ancient English proverb. But a weirdly puzzling historical fact is that the hellish brutality of battlefield violence can be both neutralized and rendered aesthetically attractive to media audiences. In the 1920s, broadcasting media were used for the first time by ruling groups to beautify war, as the German literary critic Walter Benjamin spotted. In the age of mechanical reproduction, he commented, war came wrapped in “illusion-promoting spectacles” charged with ‘aesthetic pleasure’. Despite Benjamin’s one-sided conviction that fascism was the prime driver of this aestheticization of war – he had little to say about the parallel contributions of Soviet communism – and although in the difficult political circumstances he probably didn’t get to watch Triumph des Willens (1935), Olympia (1938), and other propaganda films of Leni Riefenstahl or the Nazis’ 1944 documentary “Beautiful Theresienstadt: the Führer Gives Jews a City”, he correctly foresaw that electronic media could have electrifying effects – that radio and film would be used to adorn war for mass consumption by turning its life-and-death horrors into multi-media entertainment.

The public beautification of war – I speak descriptively, if sarcastically – is among the oddest features of the meta wars of our century. With the help of communications media, war becomes an elaborately staged, picturesque tableau designed to transfix audiences and wall them off from war’s horrors. Savagery and ghastliness are no more. War becomes bloodless. It undergoes a form of beautification more subtle and more insidious than ever happened in the era of radio, film, and television. Our wars are ‘meta’ in the sense that they undergo a gamification. It is as if audiences living outside of war zones are invited to enter and immerse themselves in rooms in which wars are no longer violent, beastly, or soul destroying, entertainment rooms in which nobody has their brains or chests blown out, or is crushed under rubble, left limbless, scarred emotionally for life, or forced to live with broken hearts in ruined ecosystems. Yes, media reports are awash with dazzling images of drones in the sky, tanks advancing across fields, guns fired by ear-muffed soldiers in uniform, clouds of black smoke, and blackened buildings. Yes, there are press conferences, footage of diplomats sitting around flagged tables, war cabinet meetings, official warnings about “terrorism”, and predictions of progress. And, yes, there is non-stop deployment of metonyms, keywords, clichéd phrases. Incursions, evacuations, unconfirmed reports, footholds, confrontations, ground assaults, front lines, power targets (an Israeli specialty, matarot otzem, the total destruction of hospitals, high-rise residences, universities, mosques, and other civilian targets), safe zones, abandoned villages, military analysts speaking on the condition of anonymity, intelligence reports, cease-fire negotiations, civilians fleeing fighting, overcrowded shelters, tent camps, and peace talks. But war seems no longer to be death’s feast.

AS: The word “indifference“ runs though your interpretation of 21st century wars. You suggest that despite the seemingly overwhelming flow of information about current affairs and wars in particular, a growing number of inidividuals (especially in some parts of the globe) have become more and more indifferent towards wars that are mushrooming in our times. What are the roots/causes of the growing indifference you insist upon? Is it a result of the “technologization” of society or other factors of human development?

JK: Widespread citizen indifference toward the cruelties and horrors of war is among the effects of the gamification of war. It’s true that geographically speaking indifference is unevenly distributed; when the claws and teeth of a meta war sink into people’s skins, their indifference is quickly dissolved by concern laced with fear and anger. It’s true as well that there are contexts, contemporary Israel and the United States after 9/11 for instance, wherein mainstream media coverage of meta wars has aroused bellicose passions and loud calls by citizens to wage war on enemies ruthlessly, to the bitter end of total victory. For a variety of reasons, my judgment is that these examples of the passionate mobilization of war-mongering masses are outliers in decline. I may be wrong, but the age of democratic wars, considered by many scholars to have been born of the second half of the 18th century, is coming to an end, most obviously because, functionally speaking, the weapons of war, most of them overkill weapons, render obsolete mass mobilization and universal conscription. It’s true that the warrior songs are still sung – Aux armes, citoyens; Formez vos bataillons; Marchons, marchons [Shoulder arms, citizens; form your battalions; march, march] – but the figure of the arms bearing citizen is nowadays replaced by audiences whose awareness of destruction and killing is muted by incuriosity, detachment, impassivity.

Source: Frame Stock Footage/shutterstock.com

The indifferent person, charmed, calmed, and pacified by media spectacles and the beautification of war and overloaded with other multi-media stories and multiple life commitments in a hyper-digitalized world, withdraws from public life. The indifferent know there are wars happening, but they choose to ignore their details. With a shrug of the shoulders and frowns on their face, they turn their back on their realities. When the topic of war arises and when public disagreements about wars erupt, they say things like ‘Whatever’, or ask ‘Who cares?’ or ‘What am I supposed to do?’, without expecting a reply. As in Alberto Moravia’s classic novel Gli indifferenti [The Time of Indifference] (1929) and Jonathan Glazer’s film The Zone of Interest (2023), the indifferent person is practised in the arts of detachment. The indifferent may be well satisfied with life, happy, cheerful, and perfectly polite. They typically have multiple preoccupations such as money, family, friends, sport, work, hobbies, and holidays. They may be bored with life or generally uninquisitive about the world. They curse politicians and have little or no faith in high-level politics; their indifference is oiled by gut convictions that in matters of government, power, and world affairs their views count for zilch. The indifferent character is benumbed by war. They are certainly not ignorant. Psychoanalytically speaking, indifference is more than the phenomenon of what Stanley Cohen called ‘denial’. But it is hard to plumb the depths of people’s indifference, or to make generalizations. Is their indifference ultimately a form of strategic avoidance, a calculation rooted in fears of losing their jobs and ruining their own reputations? Do their hearts say yes, but their attention spans say no? Are indifferent people ‘copium’ addicts, in the words of the Dutch media scholar Geert Lovink, who deal with cascading disasters by abandoning politics, killing time, going easy with life, quitting the hustle, ordering takeaways, chilling, and constantly checking their socials?

I don’t know how best to answer these questions. But what I can say is that although indifferent people catch glimpses of war’s horrors, they’re gripped by feelings of emotional disconnection and cold unconcern. They’re busily preoccupied with their own cluttered lives. Gripped by war fatigue, they say suffering isn’t their thing. They conclude that these wars are not their business, or beyond their control, and that, when all is said and done, nothing can be done about them because wars are the way of a corrupted and greedy world run by rich and powerful elites.

AS: You brought up the issue of the normalisation of nuclear weapons. How does this strange acceptance of nuclear weapons affect our present societies as well as the future prospect of global co-existence? Can we still call it a war as we know it or this is something that falls beyond human experience and even imagination? Philosopher and social thinker Ivan Illich once refused even to talk about nuclear weapons. He joined silent protest groups because nuclear weapons seemed to him to belong to the sphere of unspeakable. Are we now dealing with a totally different kind of silence, or rather are we silently accepting something that should never be normalized?

JK: While I have great sympathy for Illich’s view, saying the unsayable and speaking frankly about nuclear weapons are today urgent priorities, if only to shake the world and put an end to the false belief that nuclear weapons make the world a safer place. One way of doing this is to think historically about war’s weapons. Any cursory glance at the past should underscore the elementary point that war is not only a human fabrication – an invention like any other of the inventions by which we order our lives, such as writing, marriage, cooking our food instead of eating it raw, as the anthropologist Margaret Mead once noted. Through time, the modes and means of war have undergone significant alterations. Historians typically define war as a mutually recognized conflict between two or more groups as groups, in which each group puts an army, however small, into the field to fight and kill, if possible, some or all the members of the other group’s army. While they often disagree about matters of timings and technologies, they help us realize, for instance, the profound military and political significance of newly invented weapons (the sword, Greek fire, crossbow, the machine gun, chemical weapons, the atomic bomb, drones) and changing modes of imagining and making war. We come to understand how, during the second half of the 19th century, war fought by cavalry and close infantry formations was rendered obsolete by rifles, steel cannon, and bursting shells. More chillingly, I said in my lecture, a strong sense of history forces us to ask whether the mega-destructiveness of meta wars of the Grozny-, Aleppo-, and October 7 type – the extermination of innocent civilians and their ecological habitats by air-dropped MK 80 series 2,000-pound bombs, for instance – signals the beginning of a new era in which the distinction between nuclear and “conventional” non-nuclear weapons is finally rendered obsolete.

Buffalo R4/Breakaway nuclear

test,

Maralinga Range,

September

- October 1956.

Source: Wiklpedia

As for nuclear weapons, their unregulated spread is frightening. Nine countries are today known to possess nuclear weapons, six other states host nuclear weapons, and a further 28 endorse their use. There are an estimated 12,100 nuclear warheads, two-thirds of them ready for use in active military stockpiles. While there’s been a significant decline from the approximately 70,000 warheads owned by the nuclear-tipped states during the Cold War, most observers expect the size of nuclear arsenals to grow during the coming decade. I find the whole trend obscene, in part for very personal reasons. During the 1950s and 1960s, my father was a worker on the British nuclear testing site at Maralinga, where half a dozen huge bombs were detonated and bizarre experiments with small-scale ‘battlefield’ nuclear weapons took place. He later died in great pain of multiple cancers, and so I find the present-day public indifference to the current build-up of nuclear weapons especially upsetting. It’s worth remembering: a single nuclear warhead would kill hundreds of thousands of people, with devastating humanitarian and irreversible environmental consequences. Detonating a single nuclear weapon over cities like Shanghai, Paris, Istanbul or Nairobi would kill at least half a million people almost instantly. Yet the arms race continues. Disarmament treaties are scrapped and periodically there are threatening reminders by states of their willingness to launch nuclear strikes. Talk of ‘tactical’ nuclear weapons shouldn’t fool us. Often described as ‘low yield’ and ‘smaller’, they are weapons 20 times bigger than the “Little Boy” bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. The whole trend should force us to wonder whether nuclear weapons and the so-called “balance of terror” will permanently protect our planet from human self- destruction, or whether, as the British historian of war A. J. P. Taylor once put it, a deterrent may work ninety-nine times out out of a hundred, but on the hundredth occasion it produces a catastrophe. And if it’s thought the gamble is nonetheless worthwhile, we should consider the dangers of what the historian Serhii Plokhy has dubbed nuclear folly. In the most dangerous moment of the Cold War, the Cuban missile crisis, he shows how organised deception, misunderstandings, stupidity and unintended consequences, such as near misses at sea that almost prompted a Soviet nuclear-armed submarine to fire off its weapons, miraculously didn’t result in a nuclear catastrophe. Dumb luck rescued our world from oblivion.

AS: You are concerned with the ongoing collaboration/cooperation between state power and media in democratic societies. There have been numerous cases in the past when allegedly free media proved to be very closely connected to the state and unable to resist its pressures or even willingly played a servile role. Stories of dissemination of images from Abu-Graib abuses of prisoners as well as the more recent Julian Assange affair and other cases make one think that media is even in a more difficult position in the age of digital communications than before. How do journalists and media platforms handle the coverage of wars?

JK: In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell rightly warned against war hawk politicians who twist syntax and words and spray forth the correct opinion as automatically as a machine gun spraying forth bullets. But I doubt whether he could have imagined how in the multi-media age of meta wars there’s much more than government censorship and slant and the spraying forth of correct opinions. War is aestheticized. Government platforms regularly tout media narratives designed to win public support for war, minimally by portraying war as bloodless. There is war on the language of war, new forms of meta speak in which we hear of ‘surgical strikes’, ‘autocrats’, ‘smart weapons’, ‘collateral damage’, ‘civilian casualties’, ‘humanitarian aid’, ‘terrorism’, ‘safe zones’, ‘ceasefires’, and ‘special operations’. Military manoeuvres come wrapped in multi-media publicity designed and handled by armed forces public relations professionals. Commanding officers are trained in the arts of avoiding bad publicity and gruesome realities. Government statements, reports, and press kit handouts are given to journalists. The point is to turn war into a spectacle, a tactical shooting stage performance, an Arma 3- or Battlefield 1-type video war game created and directed by the governing authorities. There are daily press conferences, where it is affirmed that there is no censorship beyond what is necessary for military victory and the safety of the troops. But war is inside their words. There are calculated morale boosts and good news from the front. A special place is reserved for men and women of bravery, legends, and heroes, some of them unknown soldiers who have laid down their lives. At every moment, the goal is to disparage the adversary, peddle the conviction that this war is a just war, deny that things are going wrong, publish instant denials, refuse to confirm or comment on operations, throw out the dead bodies when nobody is watching, and bathe bad news in satisfying silence.

The fighters, victims, and witnesses who experience meta wars first-hand will tell you that they live day and night with war in their hearts and minds and inside their guts. But that’s not how war is presented by prime ministers and presidents, politicians, government public relations specialists, and military spokesmen. In their statements, speeches, and press conferences, death and destruction are conspicuous by their absence. In democracies and despotisms alike, governments do more than ensure that ‘truth’ is a casualty of war. They indeed tell lies, bullshit, and peddle calculated silence. In the age of meta wars, states and armies do all they can to frame, slant, block, and airbrush the images, sounds, and stories of war that audiences may find disturbing. Russian-style despotisms and their state-controlled news platforms such as Vremiya specialize in crushing and criminalizing their opponents’ messages. Twitter is throttled; Facebook access is subjected to slow downs. There are no angels in metaverse wars. As you remind us, the United States and its allies hunted and hounded Julian Assange and forced him to suffer different forms of imprisonment without trial for 14 years because he decoded and circulated the collateral murder video tapes and other disturbing war documents.

I’d also like to point out that governments are not the sole source of the beautification of war. In the so-named capitalist democracies of our age, for-profit corporations and taxpayer-funded media platforms such as the BBC, the CBC, and Deutsche Welle contribute to the framing of war as a bloodless video game. There are many reasons for this. Commercial and taxpayer-funded media have a habit of bowing down and sucking up to government censors. Constrained by cost-cutting and personnel safety considerations, commercial and public service media platforms have mostly done away with foreign correspondents and no longer place journalists on battlegrounds. Instead, media celebrities like CNN’s Anderson Cooper are parachuted in to broadcast hastily selected ‘human interest’ stories befitting of their big name, big salary status. Mainstream breaking news journalism also helps ‘war wash’ and beautify war. It manufactures superficiality. It specialises in what the Dutch journalist Rob Wijnberg calls ‘hookthink’. It hunts for ‘clicks’. But when it comes to war reporting, devils are usually in the details, but detailed investigation takes time, patience, professional skill, and money. The paradox is that within the otherwise intense commercial media coverage of military conflicts, few mainstream journalists bother to investigate how meta wars are ecocidal, makers of junk, spreaders of plastics, poisoners of fields, farms, and forests, and juggernaut destroyers of our planetary ecosystems. These breaking news journalists rarely sink their teeth into the operations of state-backed corporations like Moscow’s Rostec, or BAE Systems, Europe’s largest arms contractor, or Raytheon, the world’s biggest guided missile producer, or the global giant of profit-seeking giants, the arms manufacturer Lockheed Martin. Breaking news journalists also fail to tell us what it is like to have a bullet in the back; how a mother feels when reading bedtime stories as bombs fall, or when her child is sickened by scabies or polio or starves to death in her arms; why soldiers swearing profanities force women and girl children at gunpoint to undress and burn their underwear; or why distraught relatives deem it their duty to piece together the remaining body parts of a whole family decimated by an enemy bomb.

AS: How can media gain (or perhaps) regain its status as a provider of just, balanced and nonconformist reports about wars and their causes? All of us live in a real world where pressure against speaking out the truth is really hard. Do you think serious journalism as well as subversive intellectual activities can change the current situation of silencing, by-passing or simply rejecting the truth? Are there ways of escaping the “iron cage“ of gamification and indifference?

JK: Everybody knows that in the era of meta wars multi-media information is simply and cheaply recordable, copyable, and distributable. Leaks by courageous individuals –the Wikileaks principle – are chronic. So long as they have adequate funding, alternative journalism platforms are also easily constructed. Direct challenges to mainstream commercial platforms and government-controlled media outpourings are technically much easier than in earlier times. Cat and mouse contestations are thus commonplace, helped by the fact that digital communication networks have a distributed – not centrally controlled – quality. In contrast to the age of radio and television broadcasting, existing hierarchies of power are always vulnerable to disruption in the form of digital mutinies and media storms.

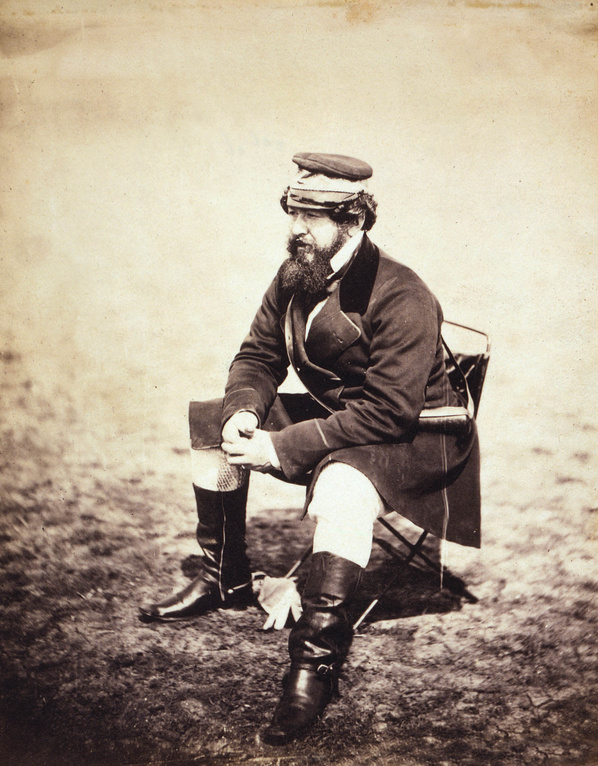

William Howard Russell (1827 – 1907), an Irish reporter

with The Times, considered one of the first modern

war correspondents. Source: Wikicommons

These opportunities offered by digital communications networks are the terrain in which a new kind of rebel journalism springs up. Judged in terms of the history of human wars, it is unprecedented. Rebel journalists contest and break the vice grip of mainstream media platforms, their fetish of breaking news, their censoring effects, and their efforts to beautify war. In place of the ‘lone star’ contrarian, reality checking journalists of the era of newspapers, radio, and television – brave and eccentric ‘ink in their veins’ heroines and heroes such as William Howard Russell, Lionel James, Martha Gellhorn, George Orwell – today’s rebel journalists more commonly operate in networked teams of less-well-known, experienced commentators who publish their carefully researched accounts and on-the-ground reports, often with the help of larger media platforms such as Al Jazeera, Haaretz, and The Guardian. Rebel journalists are a diverse group. In their ranks are experienced journalists, medical professionals, human rights observers, public intellectuals, self-trained investigators and writers, satirists, and the staff of inter-governmental agencies and commissions. They work alone or belong to not-for-profit bodies such as Médecins Sans Frontières, Middle East Eye, Oxfam, Wikileaks, the Lancet, +972, Amnesty International, the Global Investigative Journalism Network, Antiwar.com, and Quds News Network. Their work uses tools such as satellite imagery and social media feeds to unpick the decadent effects of breaking news journalism. Challenging lies and propaganda and stirring things up, pitting their own ‘truths’ against the ‘truths’ of the beauticians of war, they function as gate watchers of the mainstream gatekeepers. In matters of war, these rebel journalists are ‘semiotic guerillas’, in the words of Umberto Eco. Under difficult conditions, risking their lives when operating in battle zones, without fat-cat salaries, subject to gunfire, rocket attacks, abduction, torture, and constant internet shutdowns, they set off digital explosions. Refusing the gamification of war, they show and tell things frankly to publics, from the ground up. We could say that they do all they can to ensure that war is mediated more democratically: more openly, less entertainingly, in more plural and frighteningly down-to-earth ways. Rebel journalists digitally expose the terrible realities of the wars of our times, cast doubts on their moral and practical necessity, and teach civilians everywhere that they have the right not to suffer war, even that there is a time coming when war in every form will have to be abolished.

AS: For decades you have been studying various aspects of democracy and you are considered one of the top researchers in the field. Whatever we call democracy, it is a phenomenon that has its ups and downs: it can be continuously used and abused, it was and continues to be attacked, deformed and even abandoned as we can judge from painful realities of the last century. What are the biggest challenges for democracy in this century? And can democratic development reverse the course and character of bloody wars that according to you need to be preceded by the prefix “meta“?

JK: I have already spoken about public indifference, feelings of emotional disconnection and the cold unconcern of people busily preoccupied with their own cluttered lives. But I want to emphasise that under pressure from the new rebel journalism, this public indifference is rendered contingent. Rebel journalism helps to democratize war. By this unfamiliar phrase, I don’t mean – nonsensically, foolishly, facetiously – that war and its weapons are shared equally among peoples, or that Hobbes’ state of war of each armed person against every other armed person should be extended to the whole of our planet, as if democracy promotes something like a macabre reversal of the historic ‘ballots, not bullets’ principle. In previous writings, I have tried to make the case for a radically different understanding of democracy by explaining how democratization involves much more than constructing and defending free and fair elections, written constitutions, the rule of law, and civil liberties. Democratization is a process that runs deeper and has more far-reaching effects. It disturbs prevailing ‘realities’, ruptures reigning narratives, widens mental horizons, and enables people to embark on their own adventures. Democratization makes room for unexpected beginnings. It has a punk quality.

When seen in this way, the unorthodox phrase democratization of war thus means something counterintuitively different than what you might suppose: put abstractly, the phrase highlights the point that democracies tend to ‘denature’ war. Vibrant democracies sensitize citizens to the complexity and contingency of power relations in which wars irrupt. In matters of war, their citizens are encouraged to question dominant versions of ‘reality’ and to see that ‘truth’ has many faces. With no historical guarantees of success, democracies break down indifference and cast doubts on the ‘beautility’ of war. They expose war’s non- necessity and, thus, challenge citizens to consider the possibility of its future prevention and eradication.

Anti-war protest in Trafalgar Square, 2022. Source: Wikicommons

Anti-war protest in Trafalgar Square, 2022. Source: Wikicommons

How does this ‘denaturing’ of war happen? Most obviously, well-functioning democracies enable public rejections of war’s necessity because they functionally depend upon clusters of institutions – parliaments, civil societies, rebel journalism, independent judiciaries, human rights organizations, legal commitments to war crimes tribunals, freethinking poets, writers and musicians – which facilitate citizens’ efforts to organize themselves and to speak and act freely in opposition to war and its horrors. Robust democracies also experience normative anguish and shame about the cruelty, death, and destruction that war brings. If democracy, to put things simply, is a set of institutions and a whole way of life structured by non-violent means of equally apportioning and publicly monitoring and restraining power within and among overlapping communities of people who live within eco-settings according to a wide variety of morals, then war, the unwanted burdening and destruction of the bodies and souls of humans and their ecosystems, is anathema to its spirit and substance. Killing others violates the ethical principle of the equality of people and respect for the earthly habitats in which they dwell. But since wars also destroy ecosystems, break human hearts, poison decency, disable bodies, traumatize survivors and pave the way for follow-up wars, democracies equally encourage more realistic and pragmatic, consequentialist public objections to wars. As war becomes ever more savage, as Bertrand Russell long ago pointed out, democracies stir up citizens’ sense that very few wars are worth fighting and encourage them to see that the evils of war are almost always greater than they seem to excited populations at the moment when war broke out. Which is why, finally, wars brazenly launched by so- called democracies in the name of democracy tend to breed citizen resistance fuelled by loud public complaints about the lies, alibis, double standards, ecological risks, and moral decadence of politicians, governments, mainstream journalists, and arms manufacturers.

What I want to say in conclusion is that rebel war journalism stands at the front lines of this slow-motion democratization trend. It’s true that for all their intelligence and bravery, and despite the great violence they suffer, rebel journalists don’t and can’t stop the killing, or bring about peaceful and just endings of meta wars. But this objection about their inefficacy misses my point: despite its apparent failure to halt destructive meta wars, rebel journalism does something that is powerfully different. It does more than problematize meta wars by chipping away at their beautification. The new rebel journalism keeps alive and nurtures political hopes for an end to war.

Displaced Palestinians return to their homes in Gaza City and the north via Netzarim after a year and a

half of

displacement, as part of the ceasefire agreement, on January 29, 2025. Source: Anas-Mohammed/

shutterstock.com

Displaced Palestinians return to their homes in Gaza City and the north via Netzarim after a year and a

half of

displacement, as part of the ceasefire agreement, on January 29, 2025. Source: Anas-Mohammed/

shutterstock.com

The Author

JOHN KEANE

John Keane is Professor of Politics at the University of Sydney and a member of the Global Challenges to Democracy group at the Toda Peace Institute. His latest book is China’s Galaxy Empire: Wealth, Power, War, and Peace in the New Chinese Century (2024).

ALMANTAS SAMALAVIČIUS

Almantas Samalavičius is a Lithuanian non-fiction writer, scholar and editor. He is professor at Vilnius Gediminas Technical University‘s School of Architecture and an author of 17 books and a dozen of edited volumes. His writings have been translated into 15 languages. He has served several terms as president of Lithuanian PEN.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org