Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament Report No.209

When Is Enough, Enough? The Security Dilemma in Europe

Herbert Wulf

February 04, 2025

This report examines six key parameters that can be used for a realistic comparison of military capabilities between NATO countries and Russia: military spending, major weapons systems, troop strength, military operational capabilities, arms production and nuclear weapons. This assessment, based on reliable sources of the present military capabilities of Russia and NATO, describes the status quo. Thus, it is a static comparison that can change due to the dynamic rearmament processes on both sides. While this can only be a snapshot, it reflects the current military balance of power. The report concludes that NATO's relative strength and general conventional military superiority could be an entry point to prevent or stop the present new arms race in Europe and possibly even to resume the arms control agenda that lies in shambles. To make progress in this area, three levels should be envisaged: strategic nuclear weapons, intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe and conventional power relations in Europe.

Contents

Introduction

According to the assessment of NATO and the EU, today's Russia is the greatest threat to peace and security in the Euro-Atlantic area for the foreseeable future. NATO wants to counter this threat from a position of military strength and assesses a sizeable military deficit compared to Russia*. Is that really the case? Given the volatile security situation in Europe and the present arms build-up, is there a chance—even a remote one—for arms control?

The security dilemma in Europe

The rhetoric of rearmament and intensified investments in defence currently dominates the political discourse within NATO, fed by the perception of threat by many Eastern European NATO states. Russia's invasion of Ukraine has greatly changed sensitivities in many countries – especially in those states that share a common border with Russia. The widespread assumption is that more investments in defence are needed to prevent a Russian attack. Former Prime Minister of Estonia and now High Representative of the EU recently warned: “If Europeans don’t get serious about defence, there will be no Europe as we know it left to defend.”[1]

What military capabilities does Putin's Russia possess, and what capabilities would be needed to counter this threat? Immediately after Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine, NATO countries pledged both their support to Ukraine and to upgrade their own defence efforts. German chancellor Olaf Scholz, for example, promised in parliament: “Whatever is needed to secure peace in Europe will be done.”[2] Six key parameters can be used for a realistic comparison of military capabilities between NATO countries and Russia: military spending, major weapons systems, troop strength, military operational capabilities, arms production and nuclear weapons. This assessment, based on reliable sources of the present military capabilities of Russia and NATO, describes the status quo. Thus, it is a static comparison that can change due to the dynamic rearmament processes on both sides.

This appraisal does not take into account geographic factors and vulnerabilities (such as the threat perceptions in countries close to Russia like the Baltic states and Poland). Some militarily relevant factors, such as military operational capabilities to mobilize relevant resources, are included although they are not hard facts but soft data. Of course, such mobilization strategies can also change. The fact that battlefield tactics have changed in the Ukraine war (for example, due to the realization of a shortage of artillery shells on the battlefield or the unprecedented use of drones both for information gathering as well as attacks) has not been considered. Neither are those actions part of the analysis that are now called “hybrid war”. Consequently, the comparison of the size of military spending, major weapons systems, troop strength, military operational capabilities, arms production and nuclear weapons can only be a snapshot, but it reflects the current military balance of power.

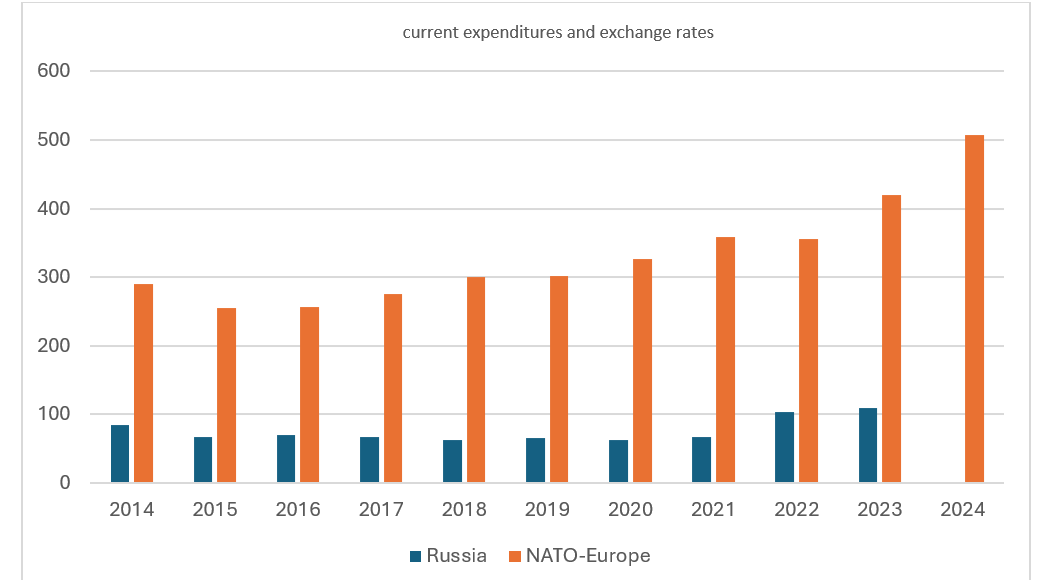

Military spending: NATO countries currently spend about ten times as much money on their armed forces as Russia ($1.19 trillion to $127 billion). Even without US spending and considering the difference in purchasing power, the clear advantage in favour of NATO remains. NATO military spending declined in real terms between 2012 and 2014, it was continuously increased again after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. Growth was at least 1.6 percent (in 2015), but most recently 9.3 percent in 2023 and estimated at 17.9 percent in 2024.[3]

Graph 1: Comparison of NATO-Europe’s and Russia’s Military Expenditures

Sources: for Russia: SIPRI, https://milex.sipri.org/sipri, for NATO-Europa: NATO, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/6/pdf/240617-def-exp-2024-en.pdf, p. 8.

Russia has significantly increased its military spending since 2022. Presently, about a third of Russia's state budget is earmarked for the armed forces and other security agencies, corresponding to about seven percent of GDP.[4] However, for economic reasons, Russia will not be able to maintain this level of military spending indefinitely. Freezing NATO military spending, or even reducing it, would not eliminate the existing imbalance in favour of NATO in the foreseeable future.

Infobox: The 2 to 5 % GDP Goal

NATO's agreement to increase national defense budgets to at least two percent of GDP is by no means based on a defense policy or military-strategic analysis, but was rather arbitrarily determined by NATO in 2014. It could just as well have been 1.8 percent, 2.5 percent or even five percent as is discussed now. It was a signal by the United States to the majority of European NATO members to contribute more to so-called burden-sharing.

In order to determine the size of a defence budget, a rational defence strategy is actually needed and not a criterion based on economic power. What are the tasks of the armed forces, how many personnel and what equipment is needed? The two-percent target is only suitable for determining how high the respective expenditure is in comparison to other member states. To choose an economic instead of military-strategic criteria can lead to unexpected results. When a country’s economy weakens and defence expenditures are stable, suddenly the country might reach the envisioned level. This was, for example, the case in Greece when it experienced a financial crisis in the 2010s.

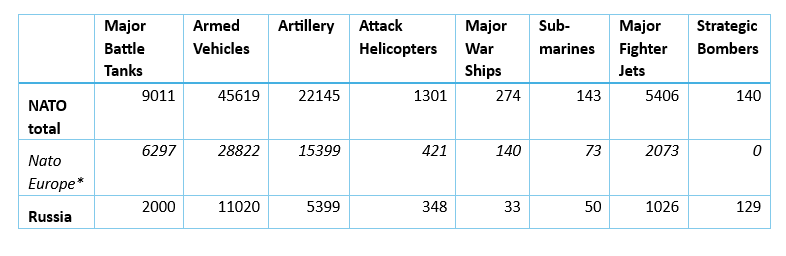

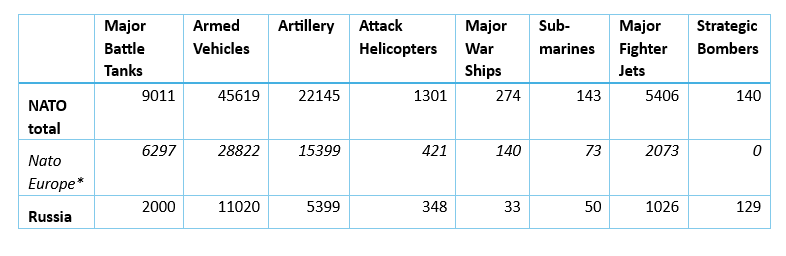

Major weapons systems: In seven of eight major weapon categories, such as fighter jets, tanks, artillery, warships etc., NATO surpasses Russia by at least three times. For example, NATO countries deploy 5,406 fighter jets (including 2,073 in Europe), whereas Russia possesses 1,026. NATO's stock of artillery pieces is four times as high as Russia’s. Only in strategic bombers does Russia come close to the USA (129 to 140).

Table 1: Major Weapon Systems

* = incl. Finland and Sweden

Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), Military Balance 2024. London.

Russia has a considerable technological backlog. And Russia is already experiencing great difficulties in compensating for the losses suffered during the invasion of Ukraine.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and as a requirement of the CFE-treaty, Russia withdrew a significant number of weapon systems but stockpiled many instead of destroying them. At that time, this included more than 11,000 battle tanks, 13,000 artillery systems and 1,000 combat aircraft. Many of them are now refurbished to be used in the war against Ukraine. The situation is different for the NATO states, which have also disarmed, but at the same time have carried out a comprehensive modernization programme. Some of the obsolete weapon programs of the Cold War, most famously the Eurofighter, continued to be used for the next 30 years or were converted for other tasks.

Russia has a considerable technological backlog. And Russia is already experiencing great difficulties in compensating for the losses suffered during the invasion of Ukraine. The statistical evaluation clearly shows that there is no need for NATO to invest so heavily in any of the classic areas of major weapons systems, even if the capacities of the USA are not considered. The decades of rearmament and modernization of equipment in NATO have led to clear advantages. In addition to the quantitative superiority, NATO's major weapons systems are usually more modern (in terms of capabilities and performance). Due to the war in Ukraine, Russia is struggling to adequately replace the lost weapon systems. Despite the enormous number of tanks—on paper, an estimated 5,000 old T-72 battle tanks—in storage, for example, it does not seem possible for Russia to transfer adequate replacements for the losses to the front.

Troop strength: The number of troops have also been substantially reduced after the end of the Cold War. The available figures underline the present imbalance in favour of NATO. The military alliance has more than three million soldiers and a large reservoir of reservists to deploy qualified personnel in a possible military confrontation. Russia's armed forces have a personnel strength of 1.32 million, thereof about 40 percent west of the Urals. Even before the attack on Ukraine, the Russian armed forces had not succeeded in reaching the specified number of personnel. On average, 200,000 positions could not be filled. A great number of qualified personnel have left Russia in 2022 and 2023. At present, the situation has deteriorated further. Casualties are high, desertions are increasing. Although recruitment policies are constantly enforced and economic incentives are offered for new recruits, it is not clear how the Russian armed forces will be able to achieve the increased targets soon and guarantee the minimum standards of training.

Table 2: Troop strength (1990, 2015, 2023, in million)

Sources: Statista, https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/379080/umfrage/vergleich-des-militaers-der-nato-und-russlands/. International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), Military Balance 2024, London. Marcel de Haas, Russia’s Military Reforms – Victory after Twenty Years of Failure. Clingendael, no. 5/2011. Steen Wegener, Introduction to the Issue of the Russian Armed Forces’ Military Capability, in: N.B. Poulsen and J. Staun (eds): Russia’s Military Might. Djöf Publishing, 2021.

Military operational capability: The ability to deploy the available troops and weapons, depends on the effectiveness of command structures, the operational orientation or the transport and supply infrastructure. A comparison of the current structures and reforms of NATO and Russia, as well as an analysis of Russia's actions in Syria and Ukraine, lead to the conclusion that Russia will hardly be able to challenge NATO in a conventional war. The modernization of NATO armed forces has been undertaken continuously. Even if the new NATO Force Model, which aims to create capacities for the mobilization and deployment of 500,000 soldiers within six months, is only partially implemented, it exceeds Russia's capabilities. Although Russia seems to have a military advantage in Ukraine, Russian armed forces find it difficult to setting up larger formations. The operational doctrine of the armed forces still seems to want to conduct offensive actions primarily by large quantities of personnel. Insufficiently trained and understaffed units are sent to overrun enemy positions. Usually, they are understaffed and partly equipped with outdated weapons. Thus, the number of casualties is high. In the meantime, Russia deploys North Korean soldiers to fight Ukraine.

The Russian armed forces lack important supporting elements to be able to carry out a large-scale ground offensive in a sustainable manner. The range of their fighter and transport aircraft is limited due to the lack of air-to-air refuelling facilities. The Russian navy does not have the ability to sustainably project power outside its own coasts (except for its nuclear submarines) and is not able to enforce supply routes across the seas around Europe. Some Western experts call NATO’s assessment of Russia an “exaggerated notion of Russian military might” and assume that “evidence of growing Russian military strength was favoured, consciously or subconsciously over analysis of weaknesses...” since this was supportive of the present security agenda.[5]

Arms procurement and production: NATO countries dominate the global arms market with over 70 percent of the total turnover (of the 100 largest arms companies in the world). Of the world's 100 largest arms companies, 42 are from the USA, 30 from the rest of the NATO countries. The NATO countries have provided considerable financial resources to expand arms production and to push ahead with further rearmament and modernization. Growth rates for arms procurement in NATO countries have often been in the double-digit range in recent years, 16.4% in 2023 and 36.9% in 2024, according to NATO information.[6]

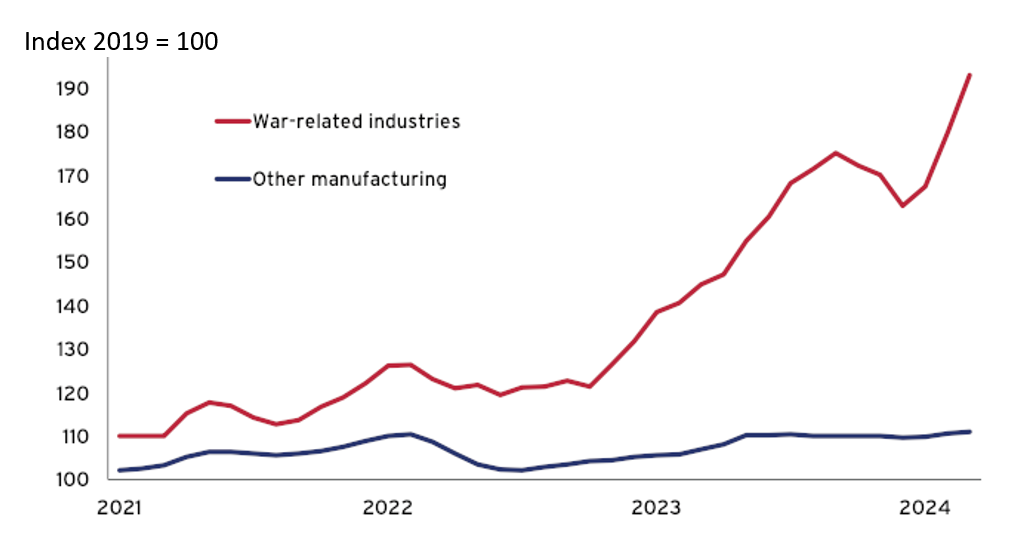

As a result of the war against Ukraine, Russia had to ramp up its arms production and is developing into a war economy. The state has begun to intervene massively in the economy. The Russian arms industry produced around 60 percent more at the beginning of 2024 than before the invasion, but without being able to fully compensate for the losses suffered in the war. Richard Connolly, an expert on Russia's defense industry at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London, calls this the "Kalashnikov economy": simple but robust. This part of the economy is “a sprawling behemoth of nearly 6,000 companies”,[7] many of which rarely made a profit before the war. But what they lacked in efficiency, they made up for in spare capacity and flexibility when the Russian government suddenly ramped up arms production in 2022. In many companies, work is now carried out around the clock in two twelve-hour shifts six days a week. Obviously, the Russian economy is in a position to intensify arms production if ordered by the Russian leadership.

Graph 2: Production by sub-industries of Russia’s manufacturing

Index 2019 = 100

Source: Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Iikka Korhonen und Elina Ribakova, Russian economy on war footing: A new reality financed by commodity exports, in: CEPR Political Insides, No. 131, May 2024, p.4, https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/203674-policy_insight_131_russian_economy_on_war_footing_a_new_reality_financed_by_commodity_exports.pdf.

The one-sided acceleration of arms production has far-reaching, serious effects on economic development in other sectors. Despite Western sanctions, Russia’s economy experienced accelerated growth rates in 2022 and 2023 but is now faced with serious bottlenecks in the labour market, slowing economic growth after the short initial period, and increasing inflation.

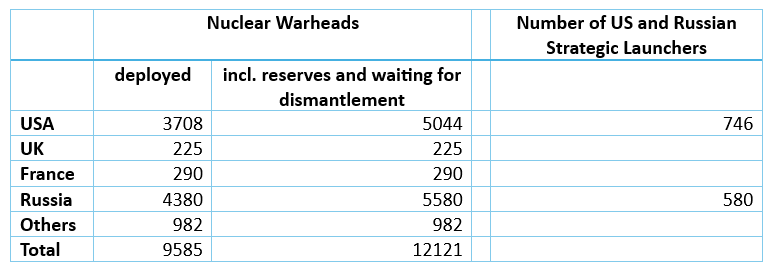

Nuclear weapons: The big “known unknown” in this comparison are the nuclear capabilities. NATO countries are superior to Russia in all conventional military areas. With nuclear weapons, there is a strategic balance. Russia and the USA possess around 90 percent of the world's approximately 12,000 nuclear warheads and the corresponding delivery systems. The three NATO nuclear weapon states USA, France and Great Britain together possess 5,559 nuclear warheads, Russia 5,580. They thus have enough explosive power to make the world uninhabitable.

Table 3: Nuclear Armed Forces

Source: SIPRI Yearbook 2023, pp.271-367

Given the second-strike capability on both sides, there exists a strategic balance. The nuclear modernization programs on both sides have set in motion a dangerous dynamic that has led to the end of existing arms control. All four countries have modernized their nuclear forces in recent years or are pursuing corresponding modernization plans.

Conclusion: A chance for arms control?

The analysis of the military capacities of NATO and Russia leaves no doubt that NATO has a position of relative strength and a general conventional military superiority. Only in the case of nuclear weapons is there parity between the two sides. Thus, there is no urgent necessity in NATO countries to further and constantly increase military spending for additional conventional armaments. On the contrary, this comfortable situation could be an entry point to prevent or stop the present new arms race in Europe and possibly even to resume the arms control agenda that lies in shambles. To make progress in this area, three levels should be envisaged: strategic nuclear weapons, intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe and conventional power relations in Europe.

In the field of strategic nuclear weapons, today’s potentials are quantitatively much lower than during the Cold War, but both the USA and Russia, as well as other nuclear powers (especially China, Great Britain and France), are pursuing an extensive modernization program to increase their nuclear options. In the United States as in Russia, it is assumed that all three pillars of the nuclear triad must be modernized and, above all, that the nuclear warheads should be overhauled.

After the end of the Intermediate Nuclear Force (INF) Treaty in 2019 and Russia's withdrawal from the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in November 2023, which the US had never signed, only the New START Treaty (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) still exists today, but it expires in 2026. But even this agreement exists only on paper. In February 2023, President Vladimir Putin suspended Russia's participation in the New START Treaty, and the US followed suit in June 2023. This means that the agreed biannual exchange of information on strategic nuclear capacities, such as locations or tests, will no longer take place.

Since Russia’s full invasion of the Ukraine, Russian officials, including President Putin, have repeatedly spoken about a possible lowering of the nuclear threshold. Russia’s nuclear doctrine does not definitively rule out the first use of nuclear weapons. Apparently, Russia’s government treats strategic and non-strategic nuclear weapons like a bargaining chip, which could also be used in extreme cases. With Russia's threat to use nuclear weapons in the Ukraine war, if necessary, it is undermining the decades-old "nuclear taboo" of using nuclear weapons only as a deterrent.

Nuclear capabilities and mutual uncertainties about these capabilities and thus the deployment scenarios are growing. There is a lack of a stable, institutionalized dialogue between the US and Russia on nuclear arms control or risk reduction. This is exacerbated by the fact that neither China, nor other overt or covert nuclear powers are part of a dialogue or even a negotiating forum. Given the current crisis-prone situation, the immediate concern is not the possibility for disarmament of nuclear weapons, but of risk avoidance to prevent a possible unwanted escalation. To avert another nuclear arms race between the US and Russia, the two governments must resume talks. The restrictions provided for in the New START Treaty can still be declared valid again. In June 2023, the United States tried to resume bilateral arms control talks. However, Russia did not respond to this.

The area of non-strategic nuclear weapons, including intermediate missile forces is particularly relevant for Europe. Russia deploys various kinds of ground-, sea- and air-launched short and medium range missiles in its war against Ukraine. Some of these missiles can also directly threaten NATO member countries. The fact that these missiles are dual capable (conventional and nuclear) is particularly worrisome. In July 2024, the governments of the US and Germany announced the planned deployment of long-range Tomahawk cruise missiles and hypersonic weapons in Germany from 2026. There are certain parallels to the NATO double-track decision in the 1979. However, the planned stationing announcement of today is not linked to an arms control offer as in 1979.

The dilemma of disarmament negotiations in the League of Nations seems still relevant today. Do states first have to invest in their security by military means before they can enter arms control or disarmament negotiations? Or is arms control the path to more security?

As typical in arms race situations, promoters of this decision assume a capability gap and want to improve NATO’s deterrence. In response, the Kremlin hinted at “mirror-like” deployments of additional medium-range missiles. Here again, the lack of an institutional arms control forum could result in unintentional nuclear escalation. This area could be an interesting opportunity to test Putin’s willingness to engage in the control of these type of weapons, even though such a willingness seems not to exist in Russia presently. But there is also no consensus on such a proposal within NATO. Some governments argue that Russia cannot be trusted now and in the future.

NATO’s present position of strength in conventional weapons should allow an offer to be made to Russia to return to arms control. This would need to be the foundation for building a European security order and for entering on the path to ending the war in Ukraine (or at least to achieving a ceasefire). Once again, there exists no functioning arms control forum at the conventional arms level. Recalling the end of the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) treaty illustrates the difficulties that are likely to be encountered. This relates particularly to the seemingly insurmountable and contradictory interpretation of NATO’s eastward expansion. The CFE treaty, originally designed during the Cold War, could not be adopted to the new geopolitical situation. The fact remains that Russia sees NATO’s eastward expansion as a threat to its security.

During the last few years, arms control has not been on the agenda. NATO countries responded to Russia's invasion of Ukraine with political and, above all, military support for Ukraine and the strengthening of their own defences. The result is the beginning of an arms race in Europe and the search for a way out has not been successful so far.

The dilemma of disarmament negotiations in the League of Nations seems still relevant today. Do states first have to invest in their security by military means before they can enter arms control or disarmament negotiations? Or is arms control the path to more security? German disarmament was proposed in the League of Nations to initiate general disarmament. But the attempted general arms limitation failed since the great powers hesitated to limit their own arms since security was associated with the possession of arms. Neither side could agree on limiting its own arms.[8] Similarly today, both sides feel compelled to continue increasing their military capabilities in response to perceived threats, which can lead to greater instability and insecurity. Presently, most security experts underline that in the face of Russian aggression it is difficult to imagine the conditions under which arms control could be initiated. As long as Russia continues to wage war against Ukraine, arms control seems impossible.

Arms control proponents, however, emphasize the chances offered by arms control, particularly in such intractable situations as Europe’s security: “Arms control engagement offers an important mechanism for understanding an adversary’s motivations and redlines better, particularly at a time when direct channels of communication are scarce. Russia’s recent threats of possible nuclear use make it more important than ever that the West understand Russian signals and that the Kremlin correctly interpret NATO intentions and moves.”[9]

How to get out of this dilemma remains the one million dollar question.

NOTES

[1] Kaja Kallas in January 2025 in her new role as EU High Representative, https://eda.europa.eu/news-and- events/news/2025/01/22/new-eda-head-kallas-calls-for-eu-single-market-for-defence.

[2] Government of Germany, statement by chancellor Olaf Scholz, 27 February 2022, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/regierungserklaerung-von-bundeskanzler-olaf-scholz-am-27-februar- 2022-2008356.

[3] Based on information by NATO, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/6/pdf/240617-def-exp-2024-en.pdf, p. 2.

[4] Cooper, Julian (2023), Another Budget for a Country at War: Military Expenditure in Russia’s Federal Budget for 2024 and Beyond, SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security, No. 2023/11, Dezember.

[5] Bettina Renz, Western Estimates of Russian Military Capabilities and the Invasion of Ukraine, in: Problems of Post- Communism, Nr. 3/2024, p. 229.

[6] NATO, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/6/pdf/240617-def-exp-2024-en.pdf, p.6.

[7] Quoted in: The Guardian 15 February 2024): Russian arms production worries Europe’s war planners, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/15/rate-of-russian-military-production-worries-european-war-planners.

[8] Magie Munro, Dashed Hopes for a Peaceful Future: How the League of Nations was Set up to Fail,in: Contemporary Review of Genocide and Political Violence, February 2020, https://crgreview.com/dashed-hopes-for-a-peaceful-future- how-the-league-of-nations-was-set-up-to-fail/.

[9] Oliver Meyer, Averting a New Arms Race in Europe, in: Arms Control Today, Arms Control Association, September 2024, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2024-09/features/averting-new-arms-race-europe,

REFERENCES

* The comparison of NATO and Russian military capabilities in this article is based on a detailed study by Christopher Steinmetz, Herbert Wulf and Alexander Lurz on behalf of Greenpeace (in German), Wann ist genug, genug? Hamburg November 2024, in which we compared these six criteria, https://www.greenpeace.de/publikationen/Kraeftevergleich_NATO-Russland.pdf.

I am grateful to Kevin Clements and Keith Krause for comments on an earlier version.

The Author

HERBERT WULF

Herbert Wulf is a Professor of International Relations and former Director of the Bonn International Center for Conflict Studies (BICC). He is presently a Senior Fellow at BICC, an Adjunct Senior Researcher at the Institute for Development and Peace, University of Duisburg/Essen, Germany, and a Research Affiliate at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago, New Zealand. He serves on the Scientific Council of SIPRI.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org