Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament Report No.205

Assad Flees Damascus for Moscow: Musings on Be Careful What You Wish For

Ramesh Thakur

December 22, 2024

This report examines the fall of the House of Assad—a regime built on terror, ruled by fear and sustained by foreign and proxy forces—which can be traced back to Hamas’s attacks on southern Israel more than a year ago. Except that instead of a Free Palestine, a Free Syria has come into being. It raises the puzzle: how does one impress upon nationalistically inflamed consciousness the enormous disparity between the goals sought, the means used and the results obtained? The second part of the article references the same discrepancy of goals, means and outcomes as a note of caution against the first instinct to euphoria over the downfall of the much-hated Assads. The third and fourth sections look at the implications for regional and global actors with significant footprints in Syria.

Contents

- Introduction

- The Israeli centre holds, the anti-Israeli axis of resistance falls apart

- Iraq, Libya and the triumph of hope over experience

- Regional actors

- Global Powers

- Nuclear breakout?

- Time to pivot from war to diplomacy

Introduction

A regime built on terror, ruled by fear and sustained by foreign and proxy forces collapsed in less than a fortnight as Aleppo, Hama, Homs and finally Damascus fell to rebels advancing from north to south in quick order. In the end, just like most dictatorships, the foundations of the House of Assad (1970–2024) too rested on the shifting sands of time. In the good ol’ days, tyrants could retire with their plundered loot into comfortable lifestyles in Europe’s most desirable pleasure haunts. No longer. The reverse damascene expulsion has seen the most recent flight of a Middle Eastern despot from Damascus to Moscow.

The beginning of the end of the Assad dynasty can be traced back to Hamas’s attacks on southern Israel more than a year ago. Except that instead of a Free Palestine, a Free Syria has come into being. This article raises the puzzle that I first asked, if memory serves right, in relation to Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic and then the US invasion of Iraq: how does one impress upon nationalistically inflamed consciousness the enormous disparity between the goals sought, the means used and the results obtained? Of course, the same question applies to Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in the interwar period, among many other examples from history. The second part of the article references the same discrepancy of goals, means and outcomes as a note of caution against the first instinct to euphoria over the downfall of the much-hated Assads. The third and fourth sections look at the implications for regional and global actors with significant footprints in Syria.

The Israeli centre holds, the anti-Israeli axis of resistance falls apart

There was a ceasefire in force when Hamas fighters attacked Israel in strength on 7 October 2023 (10/7 in short). Without that, Israeli forces would not have gone back into Gaza and still be there today. Instead, the extant status quo of 6 October 2023 in Gaza, Lebanon, Iran and Syria would have continued with very little change.

The unfolding new strategic balance sees the Israeli centre emerging much stronger while the anti-Israel axis of resistance lies in ruins. The underlying reason for this is precisely the scale, surprise factor, depraved brutality, weaponisation of sexual violence and large-scale abduction of Israelis as hostages on 10/7. The shock and awe of all that broke beyond repair the endless loop of Hamas and Israeli policies of attack, retaliate, rinse and repeat when desired. From Israel’s perspective, a new balance of power could restore a deterrence-based truce resting on the certainty of Israeli retaliation and the knowledge of Israeli escalation dominance at every level, including nuclear.

The atrocities of 10/7 were not spontaneous acts by Hamas fighters who went rogue in a frenzied killing spree, but a carefully planned pogrom. Hamas’s objectives were to kill, rape, maim, mutilate, burn, kidnap and subject to public humiliation on the streets of Gaza as many Israelis as possible, and to undermine Israelis’ confidence in their government’s ability to protect them. The political calculations by the Hamas leadership would have sought to provoke Israeli retaliatory strikes on the densely populated Gaza strip that would kill large numbers of civilians and inflame the Arab street, enrage Muslims around the world and flood the streets of Western cities with massive crowds shouting pro-Palestinian/Hamas slogans; disrupt the process of normalisation of relations with Arab states; dismantle the Abraham Accords; and isolate Israel internationally.

It’s fair to say that the political calculations behind the 10/7 attacks have been more than vindicated. Israel has never before come under such sustained international censure in international fora like the UN Security Council and General Assembly in New York, the Human Rights Council in Geneva and the World Court and International Criminal Court in The Hague. It has also been heavily criticised in many previously supportive Western capitals, streets and campuses, including in Australia.

There are still some 100 hostages captive in Gaza. Israeli soldiers are still being killed and wounded in Gaza. Hamas, Hezbollah and the Houthis retain some residual capacity to launch rockets and drones into Israel.

Yet, Israel has achieved impressive military successes in fighting throughout Gaza followed by large-scale incursion into southern Lebanon and air strikes further afield. Hamas and Hezbollah have been decimated as fighting forces, with their military commanders and leaders decapitated with a sustained campaign of targeted assassinations across the entire region including Tehran, and improvised explosive devices placed in pagers and walkie talkies. Iran has been humiliated, lost its aura of invincibility and seen the destruction of its entire strategy of trying to bleed Israel to death through a thousand cuts inflicted by its network of proxies.

The military outcome thus is a complete reset of the local balance of power to Israel’s advantage. The reason for this is a strategic miscalculation by Hamas. It launched the attacks of 10/7 unilaterally without the advance approval or, it would seem, even knowledge of Hezbollah and Iran, hoping to draw other like-minded supporters into the war if Israel retaliated. Hezbollah half did so by firing rockets but without committing ground troops. Iran got slightly sucked in to some extent but checked any further escalation after getting its nose bloodied. Bashar al-Assad apparently got firm instructions from Moscow to stay out of the war.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is right to claim that Israel’s ‘blows inflicted on Iran and Hezbollah’ helped to topple Assad, that his collapse ‘is the direct result of our forceful action against Hezbollah and Iran’.

The second strategic miscalculation by Hamas was to underestimate Israel’s will and determination to stay the military course. This is the longest war that Israel has fought, including the war of independence but not counting the intifada uprisings. Rejecting domestic and international pressure, Israel stayed steadfast on destroying Hamas as a capable military force and governing power in Gaza; relegated the rescue of hostages to an important and desirable but subordinate goal; destroyed Hezbollah and ejected it from southern Lebanon; and finally checkmated Iran as the over-the-horizon military threat to Israel via its two powerful proxies in Gaza and Lebanon.

A further consequence was to remove the props holding up the Assad regime in Damascus and leave it exposed and vulnerable to overthrow by the well-armed and strongly motivated jihadist rebels. Prime Minister (PM) Benjamin Netanyahu is right to claim that Israel’s ‘blows inflicted on Iran and Hezbollah’ helped to topple Assad, that his collapse ‘is the direct result of our forceful action against Hezbollah and Iran’.

International calls for immediate and unconditional ceasefire and urgings not to go into Rafah proved counterproductive, I believe, for two reasons. For one, given the monstrous scale of 10/7, to Israelis they separated true from fair-weather friends. For another, evidence of the extent to which Western youth and changing demographics of voters under the impact of mass immigration from Muslim countries were deserting Israel and softening on fighting antisemitism in their own populations drove home the realisation that time was against Israel. If they failed to remove Hamas and Hezbollah as security threats now, they never would. It was a case of now or never, and never is not an option for a state and a nation fighting for its very existence in its ancient homeland.

Iraq, Libya and the triumph of hope over experience

More than half a million people have died in the Syrian civil war since the heady days of the Arab spring that quickly turned into the winter of discontent, millions have been internally displaced (7 million) or become refugees (6 million) and uncounted thousands died trying to escape.

The first note of caution about the likely trajectory of post-Assad Syria is recent history. The experiences of Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya after their humanitarian liberations into freedom and democracy in the 2001–11 decade should give Panglossian optimists on a ‘new Syria’ a reality check. Like Iraq next door, Syria is not a nation-state, but a tattered patchwork quilt of different factions and faiths with a blood-soaked history of sectarian feuding. A collapse of all institutional structures if Syria were to become the Middle East’s latest failed state would send waves of instability across the region, a fresh flood of traumatised refugees into Europe and create a power vacuum for jihadists to fill.

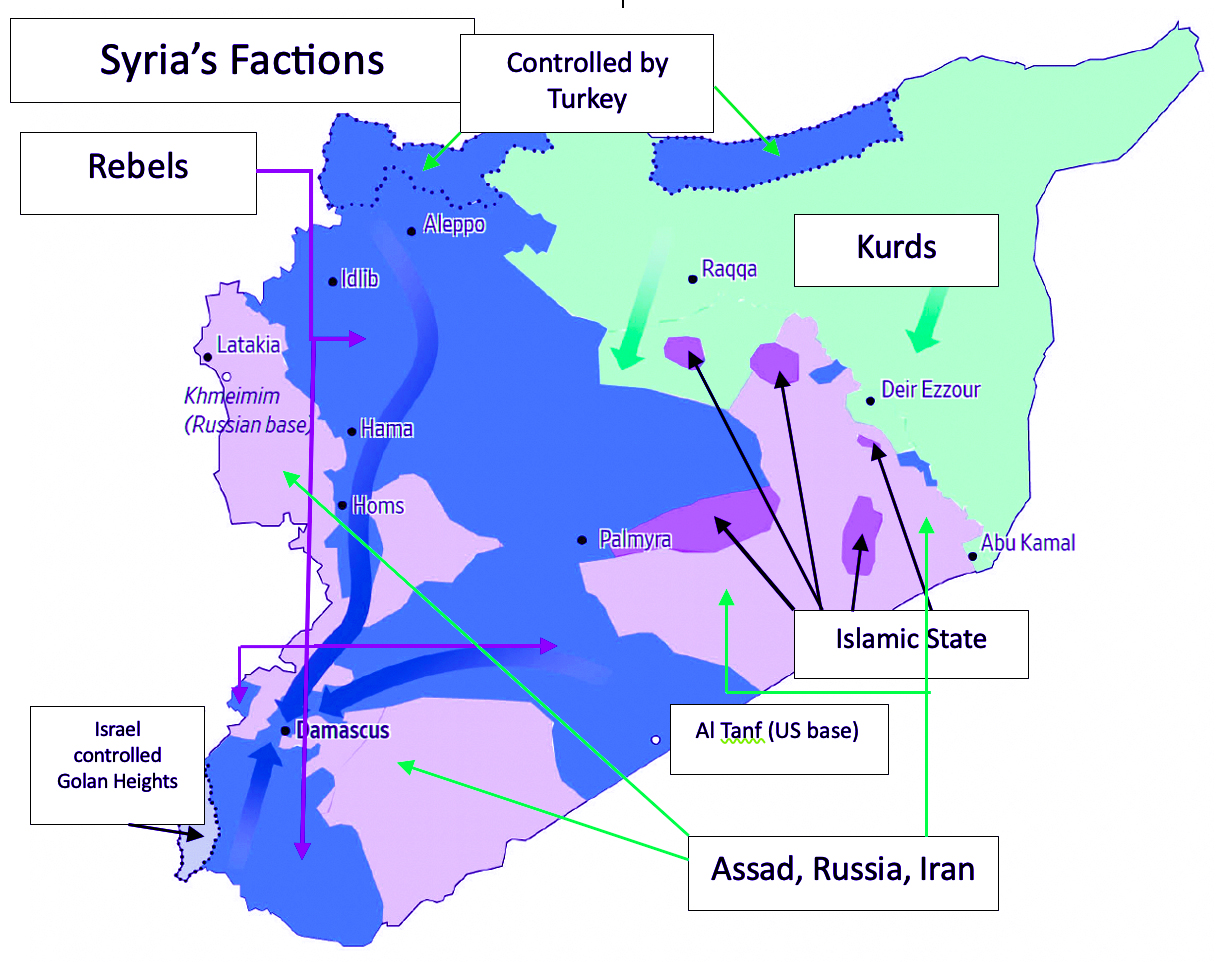

Syria’s rebels are diverse in tribe, race and religion. The kaleidoscope of rebel groups reflects the country’s history as a melting pot: Syrian National Army, Syrian Democratic Forces, Free Syrian Army. It’s not easy to spot the good guys from the bad guys among the various rebel groups and leaders. The external regional and global powers back their own favoured groups in a complex variable geometry of shifting sectarian and transactional alliances. The chances are that like counterparts elsewhere, après victory will come the deluge of warring factions and Syria descends once again into killing fields.

To describe the current situation as combustible is consequently an understatement. The dominant rebel group is the 30,000-strong Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), whose roots go back to al Qaeda and the Islamic State. Its leader is Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, the nom de guerre (with several spelling variants) of Ahmed al- Sharaa. He projects a moderate face today and wears a suit when doing interviews for Western media. Yet, in May 2017 the FBI offered a US $10 million reward ‘for information leading to the identification or location’ that enabled his arrest as the then-leader of the al Nusrah Front, ‘a foreign terrorist organization’. The HTS has been in control of Idlib in Syria’s northwest. Few analysts would describe its rule over the statelet as a model of secular modernity. Instead, it’s been closer to an authoritarian and Islamist statelet.

Looking at the religious cleavages, Sunnis dominate with around three-fourths of Syria’s total population. The remaining 25 per cent include Shi’ites, Kurds, Christians, Druze, Ismailis, Armenians. In addition, Syria’s 2.5 million Alawites (around ten per cent of the population) are a minority sect of Shi’ite Islam based around the coastal and mountain areas in the northwest. As the mainstay of the hated Assad regime, large numbers of them will seek refuge with Shi’ite allies in Iraq and Lebanon. The Iraq war had also seen a large exodus of Christians in the region. Will we experience a repeat?

Should one leader emerge from the bloodletting, almost certainly he too will be a strongman reliant on armed militias, brutal internal security services (Mukhabarat) and routine torture to maintain control. The one unknown is just how deep a shade of Islamist green his flag will be.

Regional actors

As the preceding section indicates, it will be some time before the contours of Syria’s new power equations and political order become clear. The fall of Assad will be the catalyst to a fundamental transformation of the region as well. There are several foreign players both in the immediate neighbourhood and farther afield with substantial stakes in what happens in Syria. They sense both opportunity and danger in a new Syria ruled by a tense coalition of Islamist groups. They are already positioning themselves and jockeying for influence to shape the new correlation of forces. Instant analyses suggest that the biggest winners after the Syrian people themselves are Israel, Turkey and the US while the big losers are Iran, Russia and China.

ISRAEL

It would be dangerous for Israelis to believe that Syrian’s Sunnis are immune to the anti-Israel passions that animate the Muslim masses in the region. Hence Israel’s pre-emptive strikes on Syria’s arms depots, air force bases and also naval fleet. Syria had sizeable stockpiles of weaponry, chemical weapons infrastructure and arms-production facilities. Following Assad’s fall, Israeli air strikes have destroyed up to 80 per cent of that military capacity, giving Israel air supremacy along the corridor through Iraq, Syria and Lebanon to the Mediterranean that Iran had sought to dominate. Israel has also taken control of the UN buffer zone on Syria’s side of the border in the Golan Heights, justifying it as a temporary measure. Unfortunately, the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict is a reminder of the tendency of ‘temporary measure’ to become permanent features of the region’s geopolitical landscape. Sure enough, on 15 December Israel announced plans to expand settlements in the occupied Golan Heights with the goal of doubling the population there. Incidentally, al-Golani is one spelling of al-Sharaa’s nom de guerre, which underlines his roots in that region. Critics accuse Israel of exploiting the power vacuum in Syria to grab land and create yet more facts on the ground.

TURKEY

The HTS’s principal foreign patron is Turkey which under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been pursuing ambitions to expand its sphere of influence. Not surprisingly, HTS’s victory ensures that Turkey, whose embassy in Damascus has been closed for nearly 13 years, has emerged as a big winner from the downfall of Assad. It will be the ascendant power broker-in-chief as its military, political and economic influence in post- Assad Syria grows. After Assad’s brutal crackdown on protestors as part of the Arab spring sweeping the region in 2011, Turkey took in around three million refugees and sent troops inside Syria to establish a safe buffer zone for internally displaced Syrians.

Syrian Kurds are also viewed as a potential threat to Turkey’s national security and territorial integrity, especially if they were to team up with Turkey’s own Kurds. Turkish troops have conducted several cross- border operations against them in the past. On 12 December a Turkish drone reportedly destroyed military equipment seized by Kurds in northern Syria. Turkey wants to prevent any takeover of the Syrian side of the Turkey-Syria border by the Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and to create a pro-Turkey bulwark against the SDF in eastern Syria.

Turkey has the best channels of communication of any outside power with the HTS leaders. It also claims credit for having moderated HTS’s jihadist Islamism. HTS’s triumph gives Turkey a vital interest in stabilising Syria and preventing a collapse of its political, bureaucratic and even security institutions, as happened in Iraq after the ouster of Saddam Hussein.

IRAN

In contrast to Turkey, the biggest loser of any power with stakes in the region is Iran. Its neo-imperial, anti- Israel and pro-Shi’ite network of influence in the region, meticulously constructed over decades, has been incinerated with stunning speed. When Assad’s rule was on the brink of falling in 2015, Iran and Russia stepped in to prevent collapse. After the destruction of Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon as combat- capable forces and deepening apprehensions of a second Trump administration taking up residence in the White House shortly, the loss of Syria is a strategic setback of ‘historic proportions’ and leaves Iran isolated in the region, contemplating rapidly shrinking options. Shi’ite and Persian Iran, which most Syrians hold responsible for propping up the Assad regime including by despatching Hezbollah and fighters and Iranian Revolutionary Guards forces to help his civil war, is likely to be frozen out of any zone of influence by a Sunni Arab government or coalition in Damascus. The biggest of ‘known unknowns’, in former US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s oft-cited phrase from 2002, is the impact of this strategic loss on Iran’s nuclear weapons calculus. This is a big enough question to warrant a separate section by itself shortly.

Global Powers

USA

In many respects it feels as though President-elect Donald Trump is already engaged more closely with international affairs than the incumbent President Joe Biden. Had Netanyahu heeded Biden’s serial counsels of restraint, the Gaza war would be stalemated, Hezbollah would still be in control of southern Lebanon and the House of Assad might still be standing tall in Damascus. That said, it must also be acknowledged that the periodic US criticisms from President Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and Secretary of State Antony Blinken notwithstanding, the US did not falter in its military support for Israel. That is the one relationship that Israel cannot afford to break.

Even so, Trump is likely to prove far less nuanced in supporting Israel, including perhaps defunding UNRWA and threatening to impose sanctions on the ICC (which it has not joined). On 2 December, Trump warned Hamas that there would be ‘all hell to pay’ if hostages held in Gaza are not released by the time he assumes office again on 20 January. He added: ‘Those responsible will be hit harder than anybody has been hit in the long and storied history of the United States’. Officials from the Biden White House and other countries’ diplomats told AFP news agency that Trump’s threats have already pushed Hamas into making major concessions to expedite a ceasefire, raising hopes of a truce by the time Trump takes office.

Biden has largely remained aloof from events in Syria but given no indication that the 900 US troops stationed in eastern Syria will be leaving anytime soon. On 10 December Secretary of State Antony Blinken reaffirmed ‘full support for a Syrian-led and Syrian-owned political transition’ that ‘should lead to credible, inclusive, and non-sectarian governance’. The new government, he added, must also ‘fully respect the rights of minorities, facilitate the flow of humanitarian assistance to all in need, prevent Syria from being used as a base for terrorism or posing a threat to its neighbors, and ensure that any chemical or biological weapons stockpiles are secured and safely destroyed’. Attentive listeners could no doubt hear faint sounds of a violin playing softly in the background. Nor can any US president be indifferent to the fate of American hostages in Assad’s prisons, for example Austin Tice, and will also pursue repatriation of the remains of Americans who might have died in captivity during Assad’s dictatorship.

A few days later Blinken confirmed that the US was in direct contact with the HTS despite the group still being listed as a terrorist organisation. A major goal for Washington is to prevent Islamic State from regrouping in Syria. To that end, presumably the US reserves the right to launch unilateral military strikes inside Syria if it considers that necessary.

In the meantime the world has already moved on from Biden to Trump who holds that Syria is not a US conflict and it should stay out. The Trump-Vance victory marks a repudiation of the post-Cold War neoconservative Washington playbook of militarised responses to foreign policy challenges. Instead, Trump is more likely to use economic and diplomatic leverage, including with Kurds and Turkey.

During the presidential campaign, it became clear that many Americans share the Trump-Vance-Tulsi Gabbard (the Director of National Intelligence-designate) anxiety over America’s addiction to intervening and meddling in foreign conflicts whose net effect has been to destabilise countries and entire regions. In the arc stretching from Afghanistan through Iraq to Libya, the legacy of US interference is broken societies, failed states and ruined economies. On 7 December, responding to the fast-developing events in Syria as the rebels made rapid gains against Assad’s forces, Trump posted on his Truth Social platform:

Syria is a mess, but is not our friend, & THE UNITED STATES SHOULD HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH IT. THIS IS NOT OUR FIGHT. LET IT PLAY OUT. DO NOT GET INVOLVED!

Yet he and the new Secretary of State Marco Rubio may well repeat the mistake of a hardline stance against Iran.

RUSSIA

Ensnared and overstretched in the war of attrition in Ukraine that is nearing its third anniversary, Russia could do little to help Assad check the rapid dismantling of his rule by the rebels. This will add to doubts about Russia’s reliability as a guarantor for client regimes elsewhere. Like Iran, Russia will be handicapped in efforts to cultivate working relations with the new government because of its long association with the Assad regime, its military support for Assad in crushing rebels since 2015 and for providing a haven for the Assads to which they have fled from Syria.

Yet, Russia has material interests tied up in Syria. Its naval base in Tartus, to which Russia has had access since 2013 and for the use of which it signed a 49-year lease in 2017, has been a key bridgehead in the region, allowing it to shadow NATO forces around the Mediterranean. The Russian airbase in Khmeimim near Latakia on northwest Syria’s Mediterranean coast, was used not just to strike Syrian rebels but also to support mercenaries in parts of Africa.

Still, recalling that great powers have permanent interests, not permanent friends and allies, President Vladimir Putin will explore possibilities of mutual accommodation with the new regime. On 14 December The Telegraph reported that Moscow believes it is close to striking a deal with the HTS to maintain its Khmeimim and Tartus bases. Conversely, the loss of its sole overseas naval base will strengthen Russia’s determination never to return Crimea to Ukraine. The loss of both the air and naval bases would severely crimp Russia’s force projection capability, further damaging its superpower status.

CHINA

China’s setback may not be in the same league as Iran’s and Russia’s, but is still substantial. It had given strong diplomatic backing to Assad and provided assistance in rebuilding the country torn asunder by the bitter civil war. Chinese researcher Yang Xiaotong, writing in the Asia Times on 13 December, notes that the Uyghur separatist group Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP), founded in Pakistan, has been fighting alongside HTS in Syria. It’s been designated a terrorist organisation by China, which blames it for several terrorist attacks in China in 2008–15, and by the UN. As Chinese pressure curtailed its presence and activities in Pakistan and Afghanistan, the TIP moved base with Turkey’s blessing to HTS-controlled Idlib in Syria. According to Yang, Abdul Haq al-Turkistani, the Emir of the TIP, has proclaimed that after Syria, ‘the soldiers of Islam must be ready to return to China to liberate Xinjiang from the communist occupiers’.

Nuclear breakout?

On 8 May 2018, President Trump pulled out of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) that had contained Iran’s suspected nuclear weapon program. The decision to walk away from an international agreement that had been multilaterally negotiated, unanimously endorsed by the UN Security Council and was being faithfully implemented by all other parties, was exceptionally egregious. The robust dismantlement, transparency and inspections regime had drastically cut back sensitive nuclear materials, activities, facilities and associated infrastructure. It had also opened Iran to unprecedented international inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) which to the end continued to certify Iran’s compliance with the deal.

Having earlier broken unilateral assurances to Russia on NATO’s geographical limits, the breach of the JCPOA further underlined US untrustworthiness. This damaged US credibility with its major European allies, China and Russia and also undermined efforts to reach an agreement on North Korea’s denuclearisation as Pyongyang understandably demanded major and irreversible US concessions upfront and ironclad guarantees downstream. And, by jettisoning the JCPOA and imposing tough new sanctions on Iran and secondary sanctions on anyone dealing with Iran in prohibited items, Trump freed Tehran of JCPOA restrictions.

In successive decisions thereafter, Tehran increased its uranium stockpile, limited inspections, acquired the more advanced IR-6 centrifuges and increased the quantity and purity of its enriched uranium to 60 per cent instead of the 3.67 per cent limit under the JCPOA. In May the IAEA reported that Iran had increased its stockpile of 60 per cent highly enriched uranium (HEU) to 142kg and to 165kg by August. In an interview with Izvestia that was published on 17 June, IAEA Director General Rafael Gross confessed that the JCPOA now ‘exists only on paper and means nothing’. By coincidence, SIPRI’s 2024 Yearbook was published on the same day noting that under the impact of rising geopolitical tensions, the salience and role of nuclear weapons have increased in recent times.

Grossi confirmed that groups in Iran had become ‘very vocal’ in demanding that Iran travel down its own path on nuclear weapons, even if this was not yet the government’s ‘path of choice’. He described this as a ‘very worrisome’ development.

Against this backdrop, Israel’s military successes this year have proven that Iran’s strategy of relying on Hamas and Hezbollah to contain and deter Israel is flawed, that its arsenal of conventional ballistic missiles lack accuracy and punch, but that Israel can strike any target inside Iran with the probable exception, if acting without US collaboration, of hardened uranium enrichment plants that are buried deep underground. Israel has been careful not to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities thus far. Sixty per cent enrichment is within touching distance of weapon-grade 90 per cent HEU but still just this side of the threshold. Iran is the world’s only non- nuclear country producing uranium to this level of purity. US intelligence estimates show Iran already has enough fissile material to produce more than a dozen nuclear weapons.

The setbacks vis-à-vis Israel have opened up space in Iran’s domestic discourse to raise the prospect of crossing the nuclear threshold. As well as fear of pre-emptive or post-breakout Israeli and US strikes to destroy the rudimentary capability, Iran may be hesitant also because its breakout would very likely be followed by regional proliferation with Egypt, Turkey and Saudi Arabia perhaps joining the club.

The imminence of Trump’s return to the White House cannot but concentrate Tehran’s mind on this critical policy decision as the year 2024 comes to a close. On 7 December BBC News reported that after military and diplomatic setbacks in Gaza, Lebanon and Syria, Iran had decided to produce significantly more 60 per cent HEU. The Fordow nuclear plant south of Tehran is estimated to be able to produce 34kg of 60 per cent HEU per month. Grossi confirmed that groups in Iran had become ‘very vocal’ in demanding that Iran travel down its own path on nuclear weapons, even if this was not yet the government’s ‘path of choice’. He described this as a ‘very worrisome’ development.

The Wall Street Journal reported on 13 December that Trump’s aides have begun to weigh options for preventing an Iranian nuclear breakout, including if necessary through preventive airstrikes that take advantage of Israel’s degradation of Iran’s air defences. An alternative would be to bolster military pressure alongside tough economic sanctions by sending more US forces, war planes and ships to the Middle East and to sell advanced weapons to Israel to boost its offensive firepower to take out Iranian nuclear facilities in Natanz, Fordow and Isfahan. It is worth remembering too that intelligence officials in the Biden administration released the news that Iran was actively engaged in efforts to assassinate Trump, who by instinct is combative and tends to counter-punch hard and fast.

Still, are Americans really keen to have millions more Muslims seeking revenge for mass deaths caused by American military and arms?

Time to pivot from war to diplomacy

To recapitulate, Israel entered 2024 in a state of mourning, shock and extreme demoralisation following the worst single day of attacks on Jews and their one and only state in their ancient homeland. By contrast their jubilant enemies, committed to Israel’s destruction as a state and also to the expulsion of Jews from the Jordan river to the Mediterranean Sea, were celebrating the scale of the military success of the attacks on 7 October 2023 and hopeful of translating that into significant political gains in Israel, the Islamic world and around the world.

As 2024 comes to a close, Israel once again holds sway inside and over its borders. All its surrounding foes have been destroyed as security threats for the foreseeable future. Israel’s domestic state-society compact has been restored and its aura of invincibility and escalation dominance have been successfully re- established. Hamas and Hezbollah are severely weakened and demoralised with their credibility as serious military threats to Israel shot. Iran has been shown to be impotent and the Assads have fallen in and fled from Syria.

The biggest remaining threat to Israel is hubris, triumphalism and the belief that it can now safely ignore all demands and any pressure to make concessions to Palestinians. Yet, this is imperative in order to secure a lasting political deal that makes Palestinians legitimate stakeholders in the new political order and not leave them feeling like a defeated and conquered people. The military defeats of Hamas, Hezbollah and Assads in Syria and downsizing Iran as a security threat may have been necessary conditions but were never going to be sufficient for translating battlefield success into a just and lasting peace. An armed truce is always going to be at the risk of collapse and another cycle of uprisings and crackdowns. Conversely, a time of great fluidity as the region’s geopolitical tectonic plates undergo a complete reset provides a window of opportunity for creative diplomacy. The local and, with the return of Trump in a month’s time, the international situations are propitious for deal making pursued with the same determination, zeal and daring imagination that have brought Israel its military successes.

Israel has been committed to solving the military equation first and only then move to explore diplomatic solutions. With the military equation solved, the pursuit of a diplomatic solution to resolve the underlying Israel- Palestine political conflict must now be undertaken with the same sense of urgency, vision, imagination and daring that informed Israel’s military security campaigns after 7 October 2023. Otherwise, the region will fall back into the same trap of complacency, ennui and diplomatic indolence that explains why the conflict has remained unresolved for 76 years and counting. Domestic support will also begin to fracture for an indefinite hard line that continues to exact a heavy economic price and delays the return of remaining hostages.

In order to secure the future, Israel must first address the past. In the immediate aftermath of the 7 October atrocities, with a single-minded focus on recovering, retaliating and then eradicating Hamas as a security threat, Israel reacted with anger at comments that the attacks had not come in a vacuum but that there is a historical context to it. Like similar American sentiments after the terrorist attacks on the US on 11 September 2001, Israelis interpreted this as blaming the victim. The timing was indeed insensitive but it is no more accurate to insist that Israel bears exactly zero responsibility for the stalemate in the Israel-Palestine conflict as to completely absolve the history of US foreign policy behaviour for 9/11.

The competing moral arguments coalesce around the deeply internalised beliefs that reparations for the Europeans’ genocide against Jews were paid in Palestinian currency, versus the right of Israel to exist as the Jewish homeland that was earned with the lives of millions of Jews exterminated in the Holocaust. I should add from my own direct experience at the highest levels in the UN community, meaning both senior UN officials and also several countries’ Permanent Representatives, that many do understand that several UN resolutions are one-sided, anachronistic and unrealistic and impractical. They continued to be cited and reaffirmed in fresh resolutions nonetheless, for the simple reason that there is determined opposition to conceding political victory to Israel as a reward for years of intransigence in acknowledging and righting the wrongs done to Palestinians. International reactions to the Gaza war since October 2023 show that there is a diplomatic price to be paid for the failure to negotiate a just peace. Rather than get trapped once again in the diplomatic quagmire of tit-for-tat bickering and recriminations, Israel should aim for an outcome that combines peace with justice for all from the position of strength it has achieved.

The Author

RAMESH THAKUR

Ramesh Thakur a former UN assistant secretary-general, is emeritus professor at the Australian National University and Fellow of the Australian Institute of International Affairs. He is a former Senior Research Fellow at the Toda Peace Institute and editor of The nuclear ban treaty : a transformational reframing of the global nuclear order.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org