Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament Policy Brief No.203

Arms Control in the Indo-Pacific Region: What Role for the Arms Trade Treaty?

Andrea Edoardo Varisco, David Atwood, Manon Blancafort and Yulia Yarina

November 08, 2024

This Policy Brief provides a distillation of a recent Small Arms Survey report that examines the Arms Trade Treaty (2013) in relation to the Indo-Pacific region. The report focuses on the different attitudes of states in the Indo-Pacific toward the Treaty: it explores how armament dynamics in this region shape states’ perceptions when defining their own security requirements and attitudes toward an instrument that aims to regulate the conventional arms trade. Further, it identifies the main challenges and obstacles to ATT universalisation and compliance in the Indo-Pacific region, and provides insights into opportunities for enhanced engagement with the Treaty by the states in the region.

Contents

- Introduction

- Arms trade in the Indo-Pacific region

- Main attitudes to the ATT in the region

- Obstacles and challenges

- Looking ahead: Opportunities for engagement

Introduction

The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) (2013) emerged out of growing international concern about the dangers and human cost of the largely unregulated international trade in conventional arms. It is the first legally binding international agreement whose object is to ‘establish the highest possible common international standards for regulating or improving the regulation of the international trade in conventional arms’, and ‘prevent and eradicate the illicit trade in conventional arms and prevent their diversion’, for the purpose of ‘contributing to international and regional peace, security and stability’, ‘reducing human suffering’, and ‘promoting cooperation, transparency and responsible action by States Parties in the international trade in conventional arms’.[1] The Treaty regulates different arms trade activities, including export, import, transit, trans-shipment, and brokering – referred to as ‘transfer’.[2]

These dimensions of the arms trade are all of relevance to the Indo-Pacific region.[3] The region occupies a strategic global position, due to its geopolitical significance, history, and economic development. It has witnessed decolonisation and many wars in the past, and today it hosts a large percentage of the world’s population, some of the main global economies, and a number of emerging global powers. Diverse and interlinked security challenges further characterise the region. These include identity-based conflicts, potential internal instability in different countries in the region, transnational organized crime activities, and one country, North Korea, is currently the focus of a comprehensive sanctions regime.

Against this backdrop, arms production and arms transfers have become increasingly important for Indo- Pacific countries.[4] At the same time, the Indo-Pacific shows one of the lowest levels of membership of the ATT, with only 11 Indo-Pacific countries currently being states parties, and nine others having signed but not yet ratified the Treaty.

This Policy Brief provides a distillation of a recent Small Arms Survey report that examines the ATT in relation to the Indo-Pacific region.[5] The report focuses on the different attitudes of states in the Indo-Pacific toward the Treaty: it explores how armament dynamics in this region shape states’ perceptions when defining their own security requirements and attitudes toward an instrument that aims to regulate the conventional arms trade. Further, it identifies the main challenges and obstacles to ATT universalisation and compliance in the Indo-Pacific region, and provides insights into opportunities for enhanced engagement with the Treaty by the states in the region.

Arms trade in the Indo-Pacific region

Security challenges and increasing geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific contribute to competition among regional and global players, including tensions between India and Pakistan, growing distrust between China and the United States and its regional partners, competing claims in the South China Sea, conflict in Myanmar, persistent insecurity in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and potential escalations of hostilities in the Korean Peninsula. These conflicts, border tensions, internal uprisings, separatist movements, and the presence of non-state armed actors have the capacity to threaten a fragile security situation. Such tensions are not only fuelled by illicit arms, but they have also contributed to the continuous growth in military expenditure since the late 1980s[6] and the region’s position as the largest arms importer in the world.[7] Furthermore, they may also influence and affect individual country positions on the ATT.

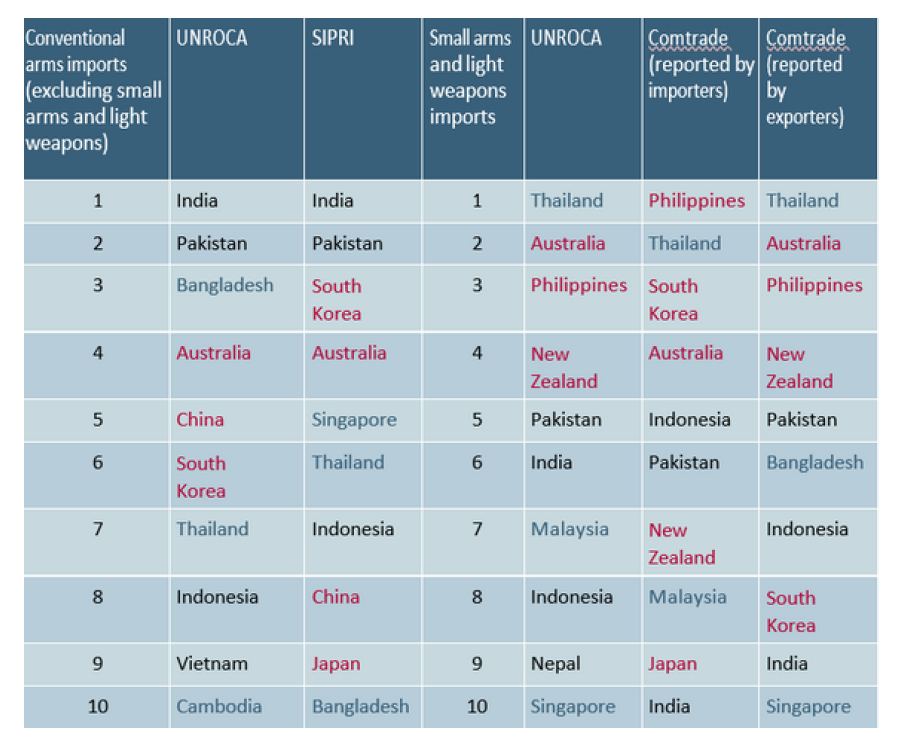

Arms trade realities vary enormously in the Indo-Pacific region. The region hosts global players in the arms trade as well as states with very small volumes of trade. Three ATT states parties—China, South Korea, and Australia—are notable regional producers and large exporters of conventional arms (Table 1). Other states are primarily importers of arms, with countries like India, Pakistan, South Korea, and Australia ranking among the top global importers (Table 2). The region also has important transit and trans-shipment hubs, such as Singapore and Hong Kong, and 14 of the 20 largest container ports in the world – with seven of the main 10 ports located in China.[8] As such, key aspects of arms transfers regulated by the ATT, such as export, import, transit, trans-shipment, and brokering, are relevant to the states in the region.

Table 1: Main exporters of conventional arms in the region, ranked by source

Notes: ATT states parties are marked in red; ATT signatory states are in blue; non-state parties are in black. In line with SIPRI’s designation, data for Taiwan, China is recorded separately from data for China.

Sources: SIPRI. n.d. ‘SIPRI Arms Transfers Database.’ Accessed 15–16 April 2024; UN Comtrade (United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database). n.d. ‘United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database.’ Accessed 13 April 2024; UNROCA (United Nations Register of Conventional Arms). n.d. ‘United Nations Register of Conventional Arms Database.’ Accessed 17 June 2024.

A more diverse number of states have a role in the production, exports, and imports of small arms and light weapons, with countries like Australia, China, India, Japan, and the Philippines being the principal exporters, and the Philippines, Thailand, South Korea, Australia, Indonesia, Pakistan, New Zealand, and Malaysia the main importers from the region. Other states in the region, for instance the Pacific Island countries, are involved in very small volumes of trade. Small arms, however, are more prone to be diverted, due to their widespread availability, affordability, ease of transport, and concealability. For this reason, even small amounts of trade are important, as diverted and illicit small arms, including those originating from legal trade, can have significant destabilising effects for security and human impact.

Arms trade realities vary enormously in the Indo-Pacific region. The region hosts global players in the arms trade as well as states with very small volumes of trade.

Table 2: Main importers of conventional arms in the region, ranked by source

Notes: ATT states parties are marked in red; ATT signatory states are in blue; non-state parties are in black.

Sources: SIPRI. n.d.; UN Comtrade. n.d.; UNROCA. n.d.

Illicit trade of arms affects a broad range of countries in the Indo-Pacific region. The patterns and actors of illicit trade are as diversified as the region itself, with Southeast Asia and South Asia being the most affected subregions, although East Asia and Oceania are not unaffected. The region has witnessed numerous interstate and internal conflicts throughout its history, which left some countries with a surplus of firearms. Other factors facilitating illicit trafficking include: long and porous borders, loosely controlled state stockpiles, corruption, and links to other illicit activities. Non-state armed groups present in the region range from extremists or separatists to tribal fighting groups, criminal groups, and organized crime structures. Such actors have also often received illicit arms, or been involved in arms trafficking themselves. In addition, unlicensed craft production is present in some countries of the region like Pakistan, and sanction evading activities in relation to the embargo on North Korea have been reported.

Main attitudes to the ATT in the region

As a consequence of the various realities characterising security and the arms trade in the Indo-Pacific region, different sub-regions display a mixed set of ‘attitudes’ (understood as a combination of national interests, perspectives, and experiences of states towards the arms trade and arms control legal and political frameworks) that have influenced their positions towards and the limits of their engagement with the ATT.

The sub-region of Oceania (Australia, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu) reveals within it both relatively strong commitment to the ATT (six states parties and three signatory states) as well as six states that have not become states parties to the Treaty. Two states—Australia and New Zealand—have been identified over time as leading actors in international and regional disarmament initiatives since the early 1990s. In the sub-region, there have also been a number of regional security- related initiatives in the past, including the most recent Boe Declaration of 2018 and the Peace and Security area of the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent.[9]

Oceania has one of the lowest levels of both armed violence and international arms trade involvement. Violence involving arms does exist: for example, ongoing violence in both urban and remote tribal areas in Papua New Guinea and, historically, coups, unrest, violence, and conflict in countries like Fiji and Solomon Islands (the three countries have not signed the Treaty, but Fiji made a recent commitment to accede to the ATT).[10] Many states in the region view the ATT as less relevant to their national security needs. For these states, other priorities, like addressing climate change, are considered more pressing, while the lack of necessary capacity to meet the obligations of the Treaty is seen as an important challenge.

Table 3: ATT membership in Oceania, as of October 2024

Source: ATT Secretariat. 2024. ‘Treaty Status’

Southeast Asia (Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor Leste, and Vietnam) presents a quite different picture. Historically, this sub-region has been at the centre of numerous armed conflicts in the 20th century and now finds itself at the intersection of a range of global power dynamics. Recent years have also seen the region become a significant market in the global arms trade amid ongoing internal and regional security threats, highlighting the dual role of Southeast Asian countries as both importers and exporters of military hardware.

These realities can be seen to have an impact among the states of the sub-region on their attitudes towards the ATT. Southeast Asia has only one ATT state party, the Philippines, with four other countries currently being signatory states. Challenges for states with respect to the ATT include: scepticism about the actual effectiveness of the Treaty in limiting arms flows to conflict settings and the sovereign right of the state to regulate its arms trade, limited awareness in some cases on some aspects of the ATT, as well as a general lack of political momentum. On the other hand, in response to the dynamics in the sub-region, some states, for instance Brunei, Cambodia, and Vietnam, have adopted stringent domestic controls over weapon possession.

As a consequence of the various realities characterising security and the arms trade in the Indo-Pacific region, different sub-regions display a mixed set of ‘attitudes’ ... that have influenced their positions towards and the limits of their engagement with the ATT.

Table 4: ATT membership in Southeast Asia, as of October 2024

Source: ATT Secretariat. 2024.

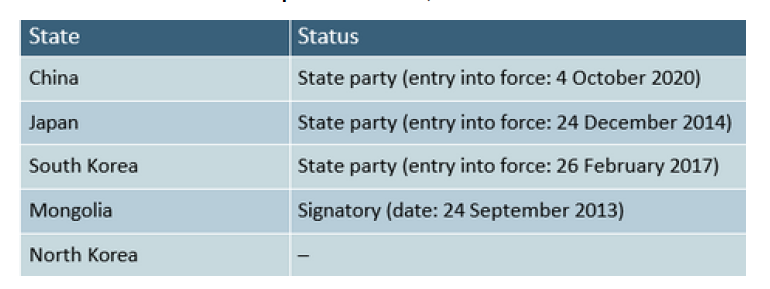

East Asia (China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, and South Korea) is host to significant actors in the global arms trade and production like China, Japan, and South Korea. North Korea—also a significant arms producer and purveyor of arms—is currently subject to a UN Security Council-imposed comprehensive arms embargo. Mongolia remains primarily an arms importing country.

Japan, South Korea, and, most recently, China, are ATT states parties and are each active players in the institutional dynamics of the Treaty. Mongolia, a signatory state, has not yet ratified the ATT, reflecting potential hesitations coupled with a careful balancing act, or challenges in aligning its national legislation with the Treaty’s provisions. North Korea formally objected to the adoption of the ATT (alongside Iran and Syria) at the plenary vote of the Final UN Conference on the ATT, preventing a consensus from being reached. It has not engaged with the process since then and remains a major player in the illicit arms trade.

Table 5: ATT membership in East Asia, as of October 2024

Source: ATT Secretariat. 2024.

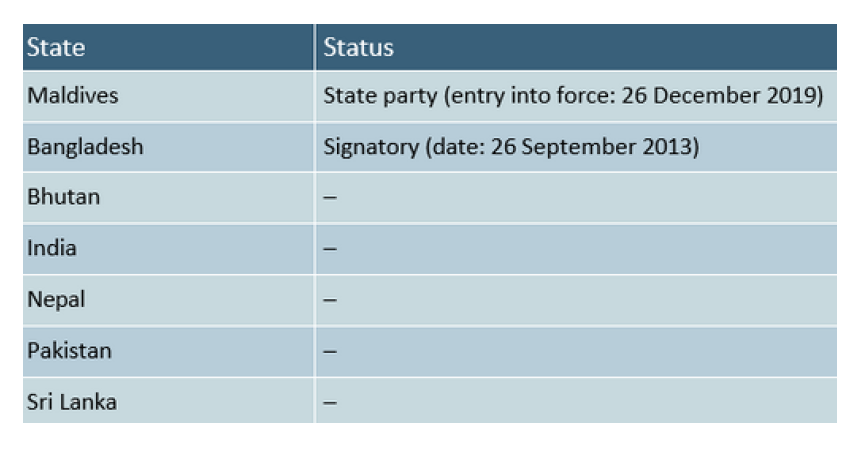

South Asia (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) is characterised by a considerable mixture of security concerns, including tensions between nuclear-armed India and Pakistan over Kashmir, the risk of arms proliferation from Afghanistan, the legacy of internal conflicts in Nepal and Sri Lanka, and degrees of insecurity within the sub-region owing to the presence of non-state armed actors.

Hence, domestic security concerns, compounded by geostrategic sensitivities and historical legacies, as well as a perceived lack of capacity by some and low political momentum overall, can all be seen as factors adding up to a very low level of ATT membership and engagement, with the sub-region having only one state party, the Maldives, and one signatory state. In addition, India’s view at the time of the negotiations that the Treaty was unbalanced in relation to the interests of arms importers and its related position as a non-state party seem to influence the views and attitudes of other states in the region.

Table 6: ATT membership in South Asia, as of October 2024 [11]

Source: ATT Secretariat. 2024.

Obstacles and challenges

The most notable concerns and obstacles that so far have limited universalisation of and compliance with the ATT in the Indo-Pacific region include:

- Domestic reservations and scepticism toward aspects of the ATT impeding universalisation. These concerns include fears that the ATT can affect a developing national defence industry or limit imports for national security purposes. In some cases, these concerns, voiced for instance by India and Pakistan during negotiations, stem from an initial disagreement persisting to this day. In other instances, states expressed scepticism about the impact of the Treaty on illicit and licit trade that has contributed to tensions within the region and beyond. They have also raised considerations of perceived limited compliance by current states parties.

- Regional security concerns and geopolitical influences amid universalisation. The lack of trust between prominent regional powers, accentuated by historical conflicts and strategic contentions, fuels national arms build-ups and enhances scepticism towards instruments like the ATT, which can be perceived to constrain national defence preparation.[12] Sub-regional tensions and disputes, such as those between Pakistan and India or in the South China Sea, contribute to shaping states’ attitudes towards arms trade and imports, and, ultimately, toward the Treaty.[13] The hesitancy of smaller states— for instance, that of certain countries in South Asia weighing the implications of India’s potential reaction to their ratification—illustrates how relations with regional players could influence decisions regarding Treaty engagement, and how targeting influential states for ATT universalization could catalyse broader regional acceptance.

- A need to build and support political momentum toward ratification and compliance and increase awareness of aspects of the Treaty. Unlike other regions of the world, regional organizations and instruments in the Indo-Pacific are either lacking or have limited engagement with arms control.[14] This poses an additional challenge for maintaining and supporting political momentum toward ratification and compliance as national governments and priorities change. Some states in the Indo-Pacific signed the Treaty more than ten years ago, but have yet to ratify it, despite the provision of outreach and assistance activities aimed at achieving this goal. These activities have sought, inter alia, to increase awareness of different aspects or articles of the Treaty that were perceived as unclear, such as brokering. Despite these efforts, challenges remain in ensuring states’ ability to secure necessary support. In addition, there is a need to engage more regularly with civil society organisations from the region that have experience and expertise on Treaty-related issues. This is particularly true of organizations concerned with the gender dimensions of arms dynamics, including the meaningful participation of women in arms control processes.

- Limited capacity and financial resources and bureaucratic hurdles. Legislative, procedural, and bureaucratic hurdles, further hindered by the complexities of interdepartmental cooperation and frequent bureaucratic rotations, may slow down the pace towards ratification or accession, and impact compliance. Domestic challenges include insufficient human resources, a lack of regular training for new officials to sustain efforts in case of turnover, and decentralized record-keeping. Treaty reporting requirements, coupled with the lack of coordination and information sharing among government ministries and agencies, can place an added strain on the resource-constrained states parties in the region. Concern about the ability to meet these reporting requirements represents an obstacle to joining the Treaty and state compliance with the Treaty is adversely influenced by actual capacity, factors which are common to other arms control instruments.

- Competing national priorities and lack of political will in universalisation and compliance efforts. For some states, universalization or national implementation is considered as a secondary priority compared to other domestic concerns, such as internal armed conflict, migration and refugees, tensions in contested land and sea borders, national development, and climate vulnerability.[15] Some countries in Oceania, for instance, may not consider the ATT as a key issue due to their limited arms trade, and instead focus on climate change as their main political priority. As such, for some states the ATT is less of a priority compared to other more pressing issues, which may fall under the mandate of the same overburdened agencies or officials.

Looking ahead: Opportunities for engagement

Analysis of the different attitudes of states from the region toward the ATT, and of challenges to universalisation and compliance, also highlights some challenges that are common in the implementation of other arms control instruments, and that arms control in general is currently facing. A series of entry points and opportunities can be discerned that could help overcome these challenges. Some of these measures are specific to the Treaty, as they target current ATT processes, working groups, and actors. Others present suggestions that can be applicable also to other instruments and contexts. For this reason, this final section primarily presents those recommendations that, while derived from the specific ATT case study, could contribute to a general debate on arms control instruments and on how advancements in universalisation of and compliance with these instruments can contribute to wider regional peace and security.

In relation to universalisation, the main recommendations are:

For actors engaged in universalisation efforts:

- Concentrate efforts on states that have demonstrated willingness to join an instrument (in this case, the ATT).

- Promote interagency awareness, acceptance, and instruments of cooperation at national level.

- Foster sub-regional processes, particularly in areas and regions where these are limited or need support, [16] to overcome states’ common doubts and fears.

For donors, exporting states, and outreach actors:

- Build a stronger evidence base for security challenges faced by states. This can help identify and address possible concerns or needs of states to focus on specific aspects characterising security and the arms trade in a region, for instance brokering or the fear of some states to be unable to import weapons for national security goals.

- Broadening the ‘lessons learned’ experience of states that have already joined an instrument, in this case the ATT. Sharing experiences from military or defence actors from other states can also increase acceptance of an instrument by reluctant defence actors.

- Build a stronger evidence base for security challenges faced by states. This can help identify and address possible concerns or needs of states to focus on specific aspects characterising security and the arms trade in a region, for instance brokering or the fear of some states to be unable to import weapons for national security goals.

- Broadening the ‘lessons learned’ experience of states that have already joined an instrument, in this case the ATT. Sharing experiences from military or defence actors from other states can also increase acceptance of an instrument by reluctant defence actors.

In relation to compliance, the main recommendations are:

For stakeholders engaged in compliance efforts (for instance, ATT states parties in the case of the ATT):

- Focus efforts on states that evidence challenges with meeting implementation obligations, for instance, by helping them create roadmaps for implementation that can help identify assistance needs, or by

focusing on specific aspects of compliance (for example, reporting), and through the example of regional ‘champions’ on implementation.

For donors:

- Build capacity of national sectors responsible for arms transfer decisions, monitoring, and enforcement.

- Support the diverse range of contributions and activities, including advocacy and oversight, promoted by civil society organisations, particularly those from the region, including those working on gender equality.

- Support the oversight and enabling role of national parliamentarians.

- Enhance multi-year forms of engagement as a way to building trust and predictability of support.

For states and other actors involved in implementation and compliance of arms control instruments:

- Foster and maintain a wider group of different civil interlocutors. These include industry and the private sector, which produce and also transport arms and ammunition. They also include regional think tanks and academic and research institutes, which can promote a research-oriented approach to security, defence, and arms control, provide evidence-based advice in support of specific activities to improve universalization and compliance, and engage with military, defence, and security actors at the domestic and international level.

NOTES

- Build capacity of national sectors responsible for arms transfer decisions, monitoring, and enforcement.

- Support the diverse range of contributions and activities, including advocacy and oversight, promoted by civil society organisations, particularly those from the region, including those working on gender equality.

- Support the oversight and enabling role of national parliamentarians.

- Enhance multi-year forms of engagement as a way to building trust and predictability of support.

For states and other actors involved in implementation and compliance of arms control instruments:

- Foster and maintain a wider group of different civil interlocutors. These include industry and the private sector, which produce and also transport arms and ammunition. They also include regional think tanks and academic and research institutes, which can promote a research-oriented approach to security, defence, and arms control, provide evidence-based advice in support of specific activities to improve universalization and compliance, and engage with military, defence, and security actors at the domestic and international level.

NOTES

[1] United Nations General Assembly. 2013. Arms Trade Treaty. ‘Certified True Copy (XXVI-8).’ Adopted 2 April. In force 24 December 2014. Art. 1. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/2013/04/20130410%2012-01%20PM/Ch_XXVI_08.pdf

[2] United Nations General Assembly. 2013. Art. 2(2).

[3] The use of the term Indo-Pacific refers to the 40 countries and economies identified by Global Affairs Canada: Australia; Bangladesh; Bhutan; Brunei; Cambodia; the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea); India; Indonesia; Japan; Laos; Malaysia; the Maldives; Mongolia; Myanmar; Nepal; New Zealand; the Pacific Island countries (14); Pakistan; People’s Republic of China (China); the Philippines; Republic of Korea (South Korea); Singapore; Sri Lanka; Taiwan, China; Thailand; Timor-Leste; and Vietnam.

[4] Dellerba, Isabelle, et al. 2024. ‘Indo-pacifique: face à la menace chinoise, les pays de la région se réarment.’ Le Monde. 17 March. https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2024/03/17/indo-pacifique-face-a-la- menace-chinoise-les-pays-de-la-region-se-rearment_6222424_3210.html

[5] Varisco, Andrea Edoardo, Manon Blancafort, Yulia Yarina, and David Atwood. 2024. Realities, Challenges, and Opportunities: The Arms Trade Treaty in the Indo-Pacific Region. Geneva: Small Arms Survey. August https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/resource/realities-challenges-and-opportunities-arms-trade-treaty-indo-pacific-region The report’s methodology included desk research, activities in the region, data gathering from open sources, and interviews with 38 people involved in universalization, compliance, and implementation of the ATT. Two research partners based in the Indo-Pacific region, the Centre for Armed Violence Reduction and Nonviolence International Southeast Asia (NISEA), also contributed to the research with two background papers and additional interviews.

[6] Tian, Nan, et al. 2024. Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023. SIPRI Fact Sheet. Stockholm:

SIPRI. April. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/2404_fs_milex_2023.pdf

[7] Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) indicates that ‘Asia and Oceania’ have been the regions with the highest volume of arms imports of the world for several decades. Wezeman, Pieter D. et al. 2024. Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023. SIPRI Fact Sheet. Stockholm: SIPRI. March. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/fs_2403_at_2023.pdf The geographical scope of Asia and Oceania, as defined by SIPRI, encompasses all countries and economies of ‘Indo-Pacific’, plus Afghanistan and Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan).

[8] CERL (Conception Etude Réalisation Logistique). 2023. ‘World Ports Ranking: The Leaders in Container Traffic.’ 11 April. https://www.cerl.fr/en/world-ports-ranking-the-leaders-in-container-traffic/

[9] Pacific Islands Forum. 2018. Boe Declaration on Regional Security: https://pacificsecurity.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Boe-Declaration-on-Regional-Security.pdf, Pacific Islands Forum. 2022. ‘2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent’: https://forumsec.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/PIFS-2050-Strategy-Blue-Pacific-Continent-WEB-5Aug2022-1.pdf.

[10] Fiji. 2023. ‘Fiji Statement: Ninth Conference of the Arms Trade Treaty (CSP9), 21–25 August 2023, Agenda Item 5 – General Debate.’ August: https://thearmstradetreaty.org/hyper-images/file/Fiji%20-%20General%20Statement/Fiji%20-%20General%20Statement.pdf

[11] Afghanistan, a state party of the ATT, is not part of the geographical scope of Indo-Pacific, as per definition in endnote 3.

[12] Lee, Jaewon. 2023. Understanding the Recent Southeast Asian Arms Build-up: A Commitment to a Minimum Military Response Capability. Issue Brief. Seoul: Asan Institute for Policy Studies. 20 December. https://en.asaninst.org/contents/understanding-the-recent-southeast-asian-arms-build-up-a-commitment-to-a-minimum-military-response-capability/

[13] Sharma, Gaurav and Mark Finaud. 2019. The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) and Asia’s Major Power Defiance—India, China, Pakistan, and Indonesia. Strategic Security Analysis, Issue 6. Geneva: Geneva Centre for Security Policy. May. https://www.gcsp.ch/publications/arms-trade-treaty-att-and-asias-major-power-defiance

[14] Among the few examples, the 2023 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Declaration on Combating Arms Smuggling, the ASEAN activities to combat transnational crime, and the Regional Roadmap on Weapons Regulations are initiatives that attempt to address issues related to weapons in Southeast Asia.

[15] NISEA. 2024. Understanding Challenges to Arms Trade Treaty Universalization in Southeast Asia. Unpublished background paper.

[16] In the field of security, ASEAN and the Pacific Islands Forum are examples of regional organisations that currently and in the past have promoted some regional initiatives on security.

The Author

ANDREA EDOARDO VARISCO

Andrea Edoardo Varisco is an arms export control expert at the Small Arms Survey. Before joining the Survey, he was the director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Arms Transfers Programme and acting director of the SIPRI dual-use and arms trade control programme. Dr. Varisco also worked as head of analytics for Conflict Armament Research and had field research experiences in conflict-affected countries in the Middle East, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. He has collaborated with several organizations in the field of arms control and disarmament, and he has authored and co-authored multiple reports on arms control. Dr. Varisco holds a PhD in Post-war Recovery Studies from the Post-war Reconstruction and Development Unit, University of York, United Kingdom, a master’s degree in International Affairs, Peace and Conflict specialization, from the Australian National University, in collaboration with the Peace Research Institute Oslo, and a master’s degree in Politics and Comparative Institutions from the University of Milan.

DAVID ATWOOD

David Atwood has worked in various capacities with the Small Arms Survey since 2012. His work has focused on small arms issues for more than 20 years, particularly international policy development. Dr. Atwood is a former Director of the Quaker United Nations Office in Geneva, where he also served as Representative for Disarmament and Peace from 1995 to 2011. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of North Carolina and an MA from the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies.

MANON BLANCAFORT

Manon Blancafort is a Project Assistant at the Small Arms Survey, supporting analysis and research on the illicit proliferation of small arms and light weapons in Afghanistan, improvised explosive devices in West Africa, and the Arms Trade Treaty in the Indo-Pacific region. Ms. Blancafort has worked at the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research and the UN Secretariat, and served as a reservist in the French Air and Space Forces. She holds a master’s degree in Peace, Security and Conflicts from the Université Libre de Bruxelles (Belgium) and an International Humanitarian Law post- graduate degree from the Université Côte d’Azur (France) and the San Remo International Institute of Humanitarian Law (Italy).

YULIA YARINA

Yulia Yarina joined the Small Arms Survey in May 2023. At the Survey she is mainly engaged in research on legal arms flows as well as small arms proliferation in different regions ranging from the Caribbean to the Indo-Pacific, as well as on various projects on gender-responsive small arms control. Ms. Yarina is a development practitioner with a background in human rights, armed conflicts, and trade. She previously worked at the Geneva UN office of Amnesty International, the Eastern Europe and Central Asia Division of the Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance (DCAF), the World Trade Organization, as well as the University of Geneva. She holds a master's degree in International Affairs from the Graduate Institute of Geneva and a diploma in law from Humboldt University with a focus on international and trade law.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org