Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament Report No.202

Triangulation - With These Friends: China, India and Russia in BRICS

Herbert Wulf

October 19, 2024

This report examines the dyadic relationships between the big three in BRICS - China, India and Russia. The XVI. BRICS summit was chaired by Russia in Kazan from October 22 to 24. Over 30 countries expressed an interest in joining the present nine members of BRICS. It can be expected that additional countries will soon join the group. What does this mean for the future of BRICS? Will BRICS become the new voice of the Global South? Or will it remain a loose grouping, a “negating coalition”, that has consensus about what to reject but that lacks a vision? This report argues that rivalries and conflicts among the big three in BRICS (China, India and Russia) prevent a homogenous global governance approach, although the international influence of BRICS is likely to keep growing.

Contents

- Abstract

- BRICS as an alternative to the current world order?

- De-dollarization

- Dyad 1. China-India: From cooperation and conflict to collision?

- Dyad 2. Russia-India: Two nations, one friendship?

- Dyad 3. China-Russia: “Strategic partnership” but who has the upper hand?

- Democratic and liberal versus authoritarian and illiberal?

- BRICS as a global player?

Abstract

Russia will chair the next BRICS summit in Kazan from October 22 to 24, 2024. Probably the most important issue on the agenda is a decision about possible new members. Some 40 countries have expressed an interest. What does this mean for the future of BRICS? Will BRICS become the new voice of the Global South? Or will it remain a loose grouping, a “negating coalition”, that has consensus about what to reject but that lacks a vision? This report argues that rivalries and conflicts among the big three in BRICS (China, India and Russia) prevent a homogenous global governance approach, although the international influence of BRICS is likely to keep growing.

BRICS as an alternative to the current world order?

China, India and Russia are the political, economic and military heavyweights in BRICS, assuring each other of their cooperation. China is the world's second-largest economic power with great geopolitical ambitions. India, now the most populous country, has experienced a dynamic development in recent years with high economic growth rates. Its government is also striving to expand its global political influence. Russia, with huge energy and raw material reserves and with great military potential, including nuclear weapons, is nowhere near as isolated internationally as it was intended in the West with comprehensive sanctions.

Is this the perfect constellation for a common global policy? What about the concrete cooperation of these major players? Where are rivalries and where are common interests? Despite cooperation in various fields, they are not a trilateral alliance within BRICS. Rather, one must consider the respective dyads, the bilateral relations between the three major BRICS countries in order to understand the possibilities for joint action, but also the respective lines of conflict.

One of the central goals of the BRICS countries, including the four new members that joined at the beginning of 2024 (Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates), is to challenge and in some ways change the current rules-based liberal world order, which is still strongly dominated by the West. “Most countries in the global South find it difficult to accept Western claims of a ‘rules-based order’ when the United States and its allies frequently violate the rules – committing atrocities in their various wars, mistreating migrants, dodging internationally binding rules to curb carbon emissions, and undermining decades of multilateral efforts to promote trade and reduce protectionism” (Spektor, 2023).

BRICS—and within BRICS, above all the three major players China, India and Russia—want to change the international system, international trade and financial relations, but also the political system, such as the United Nations and its sub-organisations.

A look at the official BRICS website, where the respective heads of government are quoted with a short introductory statement, illustrates how prominent this desire to reform the world order is. Russian President Vladimir Putin emphasizes that BRICS countries "are playing an active part in shaping a multipolar world order and developing modern models for the world’s financial and trading systems.” China's President Xi Jinping says: "We need to adjust our economic structure, achieve development of better quality, build closer economic partnership, boost the building of an open world economy and establish a global development partnership.” India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi also wants to address global challenges, stating that "corrective action must begin with the reform of institutions of global governance”. In particular, India wants to join the UN Security Council.

Interestingly, Western sanctions against Russia after its attack on Ukraine have reinforced this desire for a different, more cooperative world order. The goal of the Western alliance to isolate Russia resulted in unintended disruptions to international trade that affected not only Russia, but all BRICS countries and other countries of the Global South. That is why Putin's narrative of the need for a "multipolar world order" falls on fertile ground within BRICS and beyond. Many countries in the Global South are afraid of getting trapped in the confrontation between the great powers in the current conflict-ridden international environment. Some BRICS countries interpret their own participation in the BRICS format as a counter-model to bipolarity or Western hegemony (Maihold, Müller and Schmitz, 2024). They are interested in containing the confrontation between the great powers, also to be able to have a greater say in global politics and its rules or at least to influence them.

This desire for more creative possibilities for the countries of the Global South has also led some of these countries to reject NATO’s and the EU’s wishes to take a clear position against Russia. This is true for India, but also for countries such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, South Africa and Brazil. They are sometimes referred to as "swing states" or "fence sitters" because of their deliberative, reserved position (Kupchan, 2023). They try to maintain good relations with the different camps. This strategy of "hedging" is by no means new. Maintaining relationships with many countries at the same time has often been used to manage risks.Matias Spektor, professor of international politics in Sao Paulo, argues that the policy of hedging is understandable given the uncertain future of the global distribution of power: “Western countries have been too quick to dismiss this rationale for neutrality, viewing it as an implicit defense of Russia or as an excuse to normalize aggression” (Spektor, 2023, pp. 8-9).

De-dollarization

Even within BRICS, it is clear that a possible transformation of the world order is a lengthy process. Chinese scientists emphasize that it is therefore necessary to strengthen various areas: “Currently, several new pillars are emerging that aim to support the establishment of this new order. In the realm of security, we see the rise of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization; politically, there is the BRICS cooperation mechanism; economically, institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank are taking shape” (Wen, 2024).

The BRICS countries are striving to break away from dollar dominance by trading more with each other and moving away from the US dollar as the world's reserve currency. Initially, the BRICS countries even sought to create their own currency in order to reduce the influence of the United States in global trade. "De-dollarization" is the keyword. Decisions for a common BRICS currency have so far failed because the economic basis for it was too weak and not solid enough.

“BRICS members have turned their attention away from a shared currency and toward new cross-border payment systems with the goal of creating a more multipolar financial system. China has led this effort by accelerating its development of the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) – a renminbi settlement mechanism" (Finneset, 2024). Russia and India have announced a new partnership and want to integrate their respective payment systems (Russia's MIR and India's RuPay). Since the beginning of the Ukraine war, the currency mix of Russia's exports and imports has inevitably changed drastically. Only about a quarter of Russian–Chinese trade is now settled in dollars or euros; the larger part is now in renminbi-yuan and rubles. Just five years ago, about 85 percent of Russia's exports and two-thirds of imports were traded in dollars or euros (Kluge, 2023, p. 28). In the meantime, Russia uses the renminbi to make payments with other countries. Brazil and China agreed in March 2023 to conduct trade in their respective national currencies, the Chinese renminbi-yuan and the Brazilian real.

Are the BRICS's ideas for a redesigned world order sufficient to determine the future of the BRICS alliance? Might cooperation within BRICS even amend the rivalries and conflicts between the big three in the BRICS? To assess this question, instead of looking only at the noble declarations of intent, it is worth considering the respective three dyads at the level of economy, military and security as well as global politics’

Dyad 1. China-India: From cooperation and conflict to collision?

Of the bilateral relations between the big three BRICS countries, the relationship between India and China is the most conflictual. They maintain a complicated political, economic and security relationship bilaterally, but also within the BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the UN. They are competitors and occasionally partners, but they are increasingly on a collision course that is accelerating due to the global ambitions of the governments in New Delhi and Beijing (Wulf, 2024). It's about global political influence. Both countries are striving for more influence globally – and are getting increasingly into conflicts.

In the shadow of the major geopolitical conflict between the USA and China, a significant, possibly dangerous, competition between China and India is escalating. The world's two most populous countries, both nuclear- armed, increasingly see each other as rivals. Despite decades of efforts to find a diplomatic, internationally binding solution to the border disputes in the Himalayas, the fronts have hardened in recent years. Both sides insist on their irreconcilable positions. Neither side wants to give up even one square metre of territory (International Crisis Group, 2023).

Although neither government wants to start a war, Indian–Chinese relations are marked by conflict, competition, lack of cooperation and an increasing collision course. At the end of the colonial era, when India fought for independence from Great Britain in 1947, the division into India and Pakistan left a conflict that remains unresolved to this day. But the border between China and India also remained controversial because it was not clearly defined. In particular, the border with Tibet and Kashmir is still disputed.

Relations were not always as tense as they are today. After the end of the colonial era, the newly independent countries sought fraternal relations. Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, spoke of "Hindi-Chini bhai bhai" (Indians and Chinese are brothers), (Nehru, 1961). But Hindi-Chini bhai bhai soon became Hindi-Chini bye bye. India and China fought a bitter war in the Himalayas in 1962 with India's territorial losses (Maxwell, 1972). The trauma of the defeat can still be felt today in the discussions about their relationship.

The conflict-ridden Indo-Chinese relations are further complicated by Chinese support for Pakistan. Pakistan sees China as a diplomatic protector and a counterweight to India. In the Indo-Pakistani wars (1965 and 1999 over Kashmir and 1971 over the independence of Bangladesh), China supported Pakistan diplomatically and militarily. China became Pakistan's largest arms supplier. Almost three-quarters of all modern large-scale weapons systems delivered come from China. An iron-clad and weatherproof friendship was forged by wars and has existed now for over six decades (Fazli, 2022).

Port facilities with Chinese participation in the Indian Ocean

Source: Wulf (2024, p.32)

Over a decade ago, China announced its China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project as the centrepiece of its global Belt and Road initiative. Although the project is called an economic corridor, Beijing's strategic interests are evident (Baloch, 2017). While the CPEC is economically interesting for Pakistan, it also plays an important role militarily for China. These pipeline, road and rail connections pass through an area that is disputed between Pakistan and India. The corridor ends in the Pakistani port of Gwadar and gives China direct access to the Indian Ocean.

China's presence in the Indian Ocean is being watched with concern in India. China has systematically expanded its diplomatic, economic and military partnership with the littoral Indian Ocean countries. Although the country itself has no direct access to the Indian Ocean, it is not only involved in the port of Pakistan, but also in more than a dozen other ports that can also be used for military purposes: in addition to Pakistan, in Bangladesh, Myanmar and Sri Lanka in India's immediate neighbourhood, in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East, and in Djibouti,Sudan, Kenya and Tanzania in East Africa. For years, Indian naval experts have been warning of a Chinese "string of pearls" in the Indian Ocean. They fear a targeted strategic encirclement (Rehman, 2010) which a decade later seems to be put into practice as the map illustrates.

Conversely, China's government is concerned about India's increasing cooperation with the US. Courting India is part of the US strategy to create a counterweight to China in the Indo-Pacific. India is using its renewed popularity in the West. Prime Minister Modi promotes cooperation with the West, but his government does not want to simply be co-opted by the Western camp in the major geopolitical dispute. India's Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar speaks of "multiple alliances", i.e., changing alliances according to India’s own interests. It is a diplomatic balancing act in which, in the words of the foreign minister, it is important to "involve America, manage China, cultivate Europe, reassure Russia, bring Japan into play and expand the neighbourhood" (Tellis, 2021).

Despite the conflicts, China and India trade with each other. But there is a significant trade balance in favour of China. India imports five times more goods from China than it exports there (Govt. of India). Like the US and the EU, the Indian government is trying to reduce its dependence on Chinese products, to reduce the trade deficit with China and thus minimise risks. So far, however, with only moderate success.

Based on its strong economic potential, the Indian government is now ambitiously presenting its global claims. Ten years ago, Modi proclaimed: “We are a big country, we are an old country, we are a big power. We should make the world realise it. Once we do it, the world will not shy away from giving us the due respect and status." Xi said in 2017: “By 2050, two centuries after the Opium Wars, which plunged the 'Middle Kingdom' into a period of hurt and shame, China is set to regain its might and re-ascend to the top of the world.” Both governments pursue nationalist policies. Within society, governments are demanding recognition for their respective global roles and foreign policy demands are closely linked to power projection.

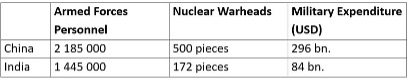

Military capabilities

Sources: Personnel: Statista; Nuclear warheads: Statista; Military expenditure: SIPRI

Both countries are investing significantly in military capacities, quantitatively in the number of soldiers and weapons, and qualitatively through constant modernization of the armed forces. In the ranking of global military spending, China is in second place after the USA and India in fourth place after Russia. China and India maintain the largest armed forces in the world, with troops of 2,185,000 and 1,445,000 respectively. If both China and India increase their military presence, the risk of a possible, unwanted collision of large proportions increases. This might not be limited to the disputed areas in the Himalayas but could affect the entire region and beyond.

China has long been a political superpower, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, one of the five recognized nuclear powers, and a dominant economic power. Now India is pushing for an equal say in world politics. But China is blocking India's ambition to become a permanent member of the UN Security Council. The potential for cooperation between the world's two most populous countries is great, but the fragile, unstable, conflict-ridden relations can also have enormous negative effects on world politics.

Dyad 2. Russia-India: Two nations, one friendship?

When India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Moscow in July 2024, he described Vladimir Putin as his "dear friend" because three things are important to him in Indo-Russian relations: India's role in global politics, India's competition with China, and the economic and military partnership with Russia. After his arrival in Moscow, Modi highlighted on Platform X the "special and strategic partnership" between India and Russia, which "will greatly benefit our people.”

What is so "special" about this "strategic partnership"? Modi once again showed that he does not want to simply join a bloc but is pursuing an independent policy. A balanced policy, as the Indian government likes to emphasize. Despite the closer Indo-American relations over the past two decades, and despite India being a welcomed partner in the EU, Japan and Australia, the Indian government is by no means turning its back on Russia. Russia's aggression against Ukraine has not changed that either. The attempt by the US, the EU and NATO to persuade India to take a tough stance against Russia after the invasion of Ukraine has failed miserably. In Moscow, Modi praised the bilateral relationship with Russia, which is based on "mutual trust and mutual respect". He avoided condemning the Russian aggression and instead spoke only in very general terms about the need to build peace.

Good relations with Moscow go back a long way to the time of the Cold War. The rapprochement with the USA and its allies has taken place only in the last two decades. And although it was a long time ago, India's political leadership has not forgotten that the Nixon administration sided with Pakistan against India in Bangladesh's struggle for independence in 1971, while the then Soviet Union supported India politically and militarily. At that time, India and the USSR concluded a 25-year "Treaty for Peace, Friendship and Cooperation". Because India is a sought-after partner today, it can cooperate with both the West and Russia, depending on its interests.

Before the trip to Moscow in July 2024, Indian officials had explicitly stressed that this summit and Indo- Russian relations were not directed against third parties. The Indian government continues to build on the policy of non-alignment that India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, practiced over seven decades ago and which is intended to emphasize India's independence. Today, the Indian government no longer speaks of "non-alignment", but of multiple alliances. The visit to Moscow was also a signal to Xi Jinping that it is not only China that maintains a "strategic partnership" with Russia.

For decades, India's arms industry has been cooperating with Russia and formerly with the Soviet Union. Around 60 percent of the Indian armed forces' weapons inventory stems from this cooperation. The armed forces are still dependent on Russian arms supplies and spare parts. But India is trying to reduce this dependence. Since the rapprochement to the West, the US has not only promised general cooperation with the Indian arms industry. It is now also supplying state-of-the-art armaments technology. Fighter jets also come from France, missiles and electronics from Israel. India is obviously trying to diversify its sources of weapons. During the 2024 visit to Moscow, Russia and India reaffirmed their commitment to continue cooperating on armaments. But cooperation with Western partners is more important for India's future armaments, because the armed forces want to reduce the priority for Russian weapons. In addition, the Russian arms industry is currently using almost all its capacity to supply its own armed forces for the war against Ukraine.

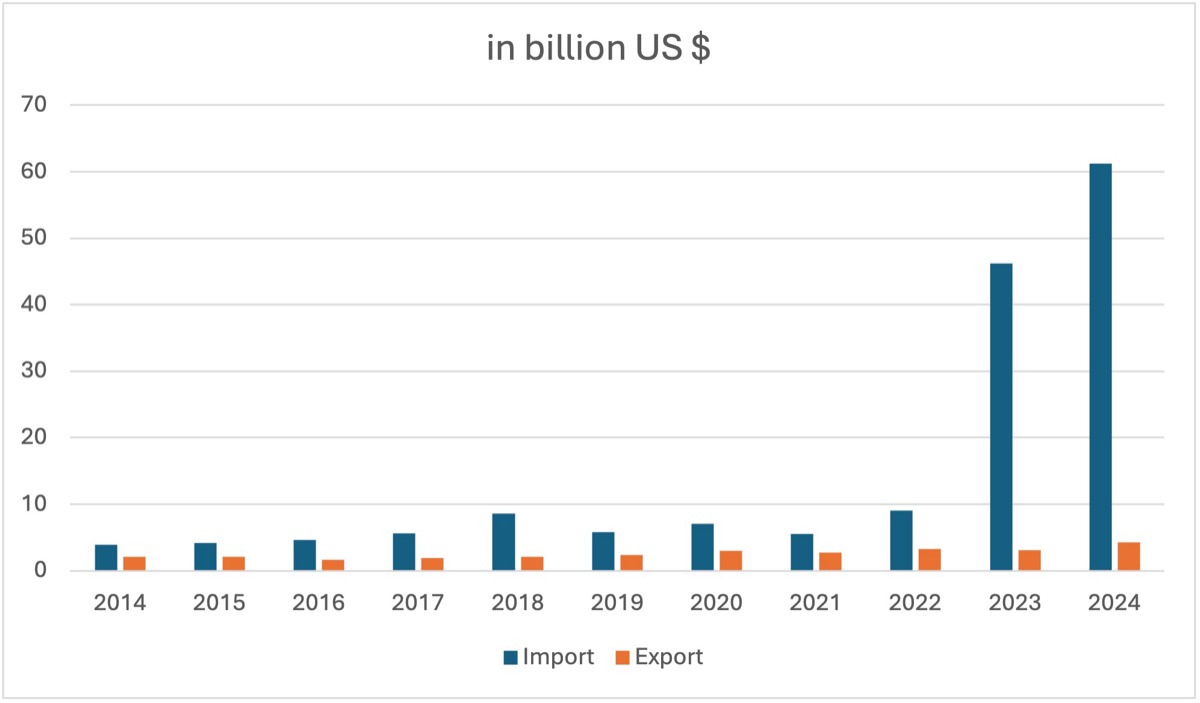

Indian imports and exports from and to Russia

Note: Budget year April – March. Statistic ends March 2024.

Source: Govt. of India

India's trade relations with Russia are considerable and, in contrast to the arms sector, they have increased significantly since the beginning of the Ukraine war. India's government has consistently refused to participate in the sanctions’ regime imposed by the West against Russia. Although Indian exports to Russia have increased only slightly, its imports from Russia increased sixfold since 2022, reaching a level of over 60 billion US Dollar in 2023-24. Raw material and energy imports from Russia are considerable. India has become the second most important buyer of Russian oil after China, which Russia finds difficult to sell on international markets. Russian oil is processed in India and exported from there, including to Europe. India's import of cheap Russian oil has helped fill Russia's war chest.

And what is important for Russia in its relationship with India? The Kremlin can show that it continues to have close and strong partnerships with countries outside its own immediate environment. Putin can thus avoid the role of international pariah intended by the West for him and counteract Russia’s international isolation.

India also sees itself as representative of the Global South and has put these concerns on the agenda both within the BRICS group and during the G20 summit in New Delhi in September 2023. Here, the interests of Russia, India, but also China and the Global South in general run parallel.

Dyad 3. China-Russia: “Strategic partnership” but who has the upper hand?

Russia's aggression against Ukraine led to drastically reduced relations between Russia and the US and EU. Reflexively, Russia turned to China. It was also the turning point in Russia's relations with China. Bilateral trade has grown dynamically, and political relations are closer than ever before. The two governments assure each other of mutual solidarity and express their own reservations about the West. Sino-Russian cooperation goes back a long way and has developed from an ideological affinity at the beginning of the Cold War and during Soviet times to a pragmatic understanding today.

During the Beijing Winter Olympics, just before Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Presidents Xi and Putin adopted a joint statement on international relations, reaffirming their "strategic partnership". China's President Xi Jinping described the bilateral relationship as "friendship without limits” (Noesselt, 2023). This is reflected in the global political orientation, economic development and cooperation in security policy. But that doesn't mean that there aren't divergences between China's and Russia's leadership. The current relationship can better be described as a partnership of convenience in which both sides pursue their own interests rather than as a real alliance (Abb and Poliankii, 2022, p. 248). They advocate a multipolar world, but do not pursue a uniform position. Russia envisions a bloc against the West, in which China also supports Russia, while China is interested in a stable world that is not dominated by the US (Sabanadze, Vasselier and Wiegand, 2024, p. 5). China has presented its own vision of a new world order through various initiatives: the Belt and Road Project, the Global Development Initiative unveiled in 2021, and the Global Security Initiative a year later.

On the one hand, China sees Russia's war as a fight against the Western-dominated world, "a goal that fits its own global ambitions" (Sabanadze, Vasselier and Wiegand, 2024, p. 6), which demands more US attention in Europe and thus less in the Indo-Pacific. The Russian Chinese partnership is described as a means to an end. At the same time, however, Russia's aggression, which violates international law, contradicts the principle of state sovereignty, the inviolability of borders and non-interference in internal affairs, which China has always emphasized internationally. Both sides, however, ignore this obvious point of disagreement.

In Russia's Ukraine war, China is behaving cautiously. China is dependent on the important trade relations with the USA and the EU. China abstained from voting on various UN resolutions concerning Russia’s aggression (Noesselt, 2023). But it still plays an important role in Russia's Ukraine war. The Chinese government has repeatedly stressed that it will not supply weapons to Russia (Kluge, 2023, p. 23). There is also no information that China has supplied lethal weapons systems. But China is a major supplier of critical dual-use goods that Russia needs to produce its weapons, especially missiles and drones (Abb and Polianakii, 2022, 247). China is thus a key country for Russia, to circumvent the Western sanctions. So far, Western pressure on China has not led to stopping this trade. In addition, military cooperation between the two countries has steadily increased in order to improve the interoperability of the two armed forces (Kluge, 2023, p. 8). China is primarily oriented towards prioritizing its own security interests.

Economically, China has become a lifeline for Russia and an indispensable partner after the imposition of Western sanctions. Of course, China rejects the sanctions. Trade has grown dynamically in recent years. Russia exports mainly fossil fuels and imports mainly Chinese technology products such as machinery, electronics and vehicles. “Moscow feared competition from Chinese goods for its own industry and wanted to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) from the People's Republic, while China was interested in expanding its exports” (Kluge, 2023, p. 8). Chinese investors were not particularly interested in direct investment, as China likes to replace Western products in the Russian market but is not interested in building up Russia as a competitor for products such as cars or other technology products (Sabadnadze, Vasselier and Wiegand, 2024, p. 10).

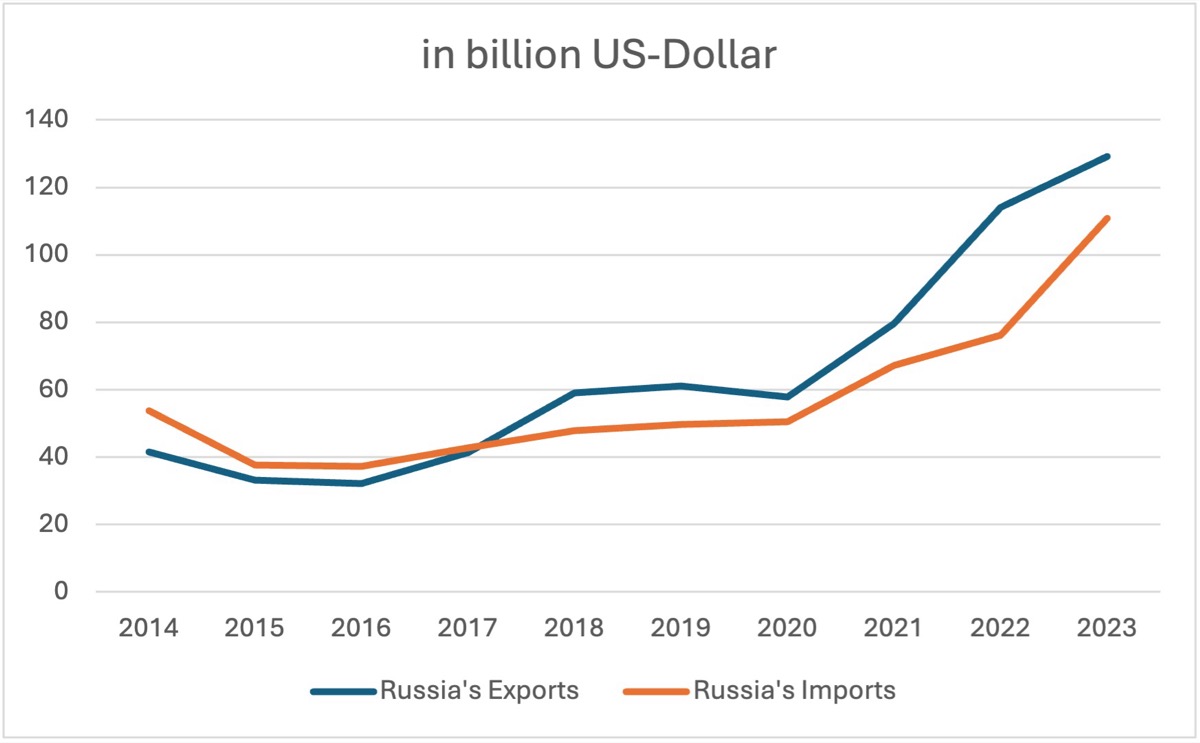

Russia's exports and imports with China (2014-2023)

Source: Statista

Russia's exports to China amounted to almost $130 billion in 2023; they have quadrupled since 2015. Russian imports were on a similar scale, rising from just under $35 billion in 2015 to $111 billion in 2023. In 2023, almost two thirds of all exports were fossil fuels.

The "strategic partnership" is not a formal security partnership and while Russia's security interests continue to lie primarily on Europe (and with NATO), Chinese interests are concentrated on the Indo-Pacific region. Economically, the differences are enormous. China's gross national product is almost ten times larger than Russia's. It's an asymmetrical relationship. While China has many options, Russia relies on China. So far, however, China does not seem to be exploiting its economically superior role. Institutional cooperation in the United Nations, the BRICS and the SCO seems to be working well. However, since Russian and Chinese interests are very different, the "strategic partnership" remains fragile.

Democratic and liberal versus authoritarian and illiberal?

The strengthening of relations within the BRICS and the SCO, but above all the partnership between Russia and China, is often seen as evidence of a possible new global confrontation between democratic and authoritarian camps (Abb and Poliankii, 2022, p. 244). However, the rapprochement of Russia/China, the upgraded geopolitical role of BRICS, the desire of almost 40 countries that also want to become BRICS members are based on common interests in specific areas rather than ideological agreement in favour of autocracy. Among those potential new members are Bangladesh, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia in Asia, Algeria, the DRC, Comoros, Gabon and Nigeria in Africa, Bolivia, Cuba and Venezuela in Latin America as well as Turkey and Kazakhstan. A new bloc formation like in the Cold War or a system of global bipolarity with the US and its allies on the one hand and Russia/China as the core of an autocratic axis on the other is not likely since BRICS is a heterogenous grouping with democratically elected and authoritarian governments.

Freedom House, which annually categorizes the countries of the world into "free", "partly free" and "unfree", within BRICS classifies only Brazil and South Africa as "free", India as "partly free" and China and Russia as "unfree". The new members Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates are all classified as "unfree".

Some statements by experts (Parello-Plesner, 2022) immediately after Russia's full-scale attack can be interpreted as an emerging competition between democracy and autocracy. NATO, for example, writes in its 2022 Strategic Concept: “Authoritarian actors challenge our interests, values and democratic way of life … These actors are also at the forefront of a deliberate effort to undermine multilateral norms and institutions and promote authoritarian models of governance” (NATO, 2022). Instead of an "authoritarian axis", it is more likely that an "alliance of autocrats" is formed who are not ideologically in line but are united in their criticism of the Western-based global order (Abb and Poliankii, 2022, p. 252).

In fact, Russia's aggression has tended to strengthen cooperation between democratic countries. “Treating the Sino-Russian partnership as a rival ideological block or even ‘alliance’ is neither an empirically correct assessment about current fault lines in world politics, nor an effective guideline for practical policy” (Abb and Poliankii, 2022, p. 245). China, in particular, criticizes the West's policy of active democratization of other countries and in this context also emphasizes again the principle of state sovereignty, territorial integrity and non-interference in internal Affairs. Russia and China are more united by fears (such as NATO's eastward expansion and US involvement in the Indo-Pacific or the security policy cooperation there with Japan, South Korea and Australia) than by common strategies to strengthen authoritarian regimes.

Within BRICS, and more generally in the Global South, many countries are trying to stay out of conflicts of bloc confrontation. This policy is also fed by their past experiences. All too often, the US and European allies have behaved hypocritically towards developing countries, as Spektor (2023) argued.

Of the 56 countries that Freedom House considers "not free", i.e., authoritarian, in 2024, (Freedom House, 2024) almost two-thirds received military aid from the USA. “It should be no surprise, then, that many in the global South view the West's pro-democracy rhetoric as motivated by self-interest rather than a genuine commitment to liberal values" (Spektor, 2023).

BRICS as a global player?

BRICS role in world politics has grown. The gross national product of the BRICS is larger than that of the G7 countries. The current BRICS countries generated almost 35% of global economic output in 2023; the G7 30%. In view of the global political situation with numerous crises, the power of the BRICS has grown. But BRICS is not a well-structured association of states; rather, it’s still a loose association that emphasizes common interests. Nor is BRICS the mouthpiece of the global South – currently, with Russia and China, rather the global East. The three big players in BRICS, Russia, India and China, have each their own agenda which runs parallel but also beyond BRICS. With the expansion of the BRICS by four countries and probably more countries in the next few years, heterogeneity will probably continue to increase, but so will the representation of the global South. The lack of interest on the part of the Argentine government and the reluctance of Saudi Arabia, which have so far rejected or postponed the offer of admission to BRICS, shows that the expansion of the BRICS is by no means a straightforward process (Ramos, 2024). For many interested countries, membership means short-term advantages, for example, in bilateral trade with other member countries. At the same time, however, it is a challenge for an expanded BRICS format to find consensus on wider goals.

BRICS has been "rightly described as a 'negative coalition' of states that quickly reach a consensus on what they reject: primarily sanctions and protectionist measures” (Maihold, Müller and Schmitz, 2024, p. 64). But other forms of cooperation are also possible, such as the admission of the African Union into the G20 at the 2023 summit. It will be important to involve the countries of the Global South in a fair way in shaping the "rules-based international order". Nevertheless, the West should not underestimate the political ambitions and possibilities of BRICS, for example, to mediate in the Ukraine war. The road to a ceasefire or peace in Ukraine runs through leading countries of the Global South. While these efforts have not yet materialized, mediation could be helpful, as was seen from Brazil in spring 2023, from African governments including BRICS member country South Africa in June 2023, and from India in August 2024.

REFERENCES

Abb, Pascal and Mihkail Poliankii, With friends like these: the Sino-Russian partnership is based on interest not ideology, in: Zeitschrift für Friedens- und Konfliktforschung, 2022, 11: 243-254, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42597-023-00090-2.

Baloch, Sha Meer, CPEC: One Potentially Treacherous Road in China's Grand Plan? Sicherheit und Frieden, 2017, 35 (3), pp. 139-143.

Fazli, Zeba, An Unwieldy Balancing Act and the Realities of a Two-Front War, in: Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy (ed), India- China Competition: Perspectives from the Neighbourhood, New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation, ORF Special Report 197, August 2022, pp. 5-10.

Finneset, Jordan, BRICS Strike Back: Russia and India Team up to Challenge Dollar Dominance, 2024, http://infobrics.org/post/41893/.

Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/FIW_2024_DigitalBooklet.pdf.

Govt. of India, Dept. of Commerce, https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/eidb/icntq.asp.

International Crisis Group, Thin Ice in the Himalayas: Handling the India-China Border Dispute, Report No. 334, November 2023.

Kluge, Janis, Russia-China Economic Relations, SWP Research Paper 16, May 2024, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/russia-china-economic-relations.

Kupchan, Cliff, 6 Swing States Decide the Future of Geopolitics, in: Foreign Policy, 6. Juni 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/06/06/geopolitics-global-south-middle-powers-swing-states-india-brazil-turkey-indonesia- saudi-arabia-south-africa/.

Maihold, Günther, Melanie Müller and Andrea Schmitz, Gestaltungsanspruch im Zwischenraum: BRICS+ und SOZ, in: Barbara Lippert and Stefan Mair (eds.) Mittlere Mächte – einflussreiche Akteure in der internationalen Politik, SWP-Studie 1, January 2024, Berlin, pp. 63 – 66.

Maxwell, Neville, India's China War, Harmondsworth, 1972.

NATO, Strategic Concept 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf.

Jawaharlal Nehru, India's Foreign Policy, Selected Speeches, September 1946 – April 1961, New Delhi: Government of India, 1961, pp. 99-102

Noesselt, Nele, Ziemlich beste Rivalen, in: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 23. Juni 2023, https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/china-und-seine-nachbarn-2023/522224/ziemlich-beste-rivalen/.

Parello-Plesner, Jonas, The War in Ukraine Turns the EU toward Rivalry with China. German Marshall Fund. 13 April 2022. https://www.gmfus.org/news/war-ukraine-turns-eu-toward-rivalry-china.

Ramos, Joshua, BRICS: Here’s How Many Countries Are Likely to Join the Alliance in 2024, https://infobrics.org/post/41847/.

Rehman, Iskander, China's String of Pearls and India's Enduring Tactical Advantage. New Delhi: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 2010, https://www.idsa.in/idsacomments/ChinasStringofPearlsandIndiasEnduringTacticalAdvantage_irehman_080610

Spektor, Matias, In Defense of the Fence Sitters: What the West Gets Wrong About Hedging, Foreign Affairs, 102, (3), Mai- Juni 2023, Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A750699374/AONE? u=hamburg&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=77518455.

Tellis, Ashley J., Non-Alligned Forever: India’s Grand Strategy According to Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, in: Carnegie Endowment, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2021/03/non-allied-forever-indias-grand-strategy-according-to-subrahmanyam-jaishankar?lang=en, March 2021.

Wen, Wang, Shifting Economic Balance: BRICS vs G7, https://infobrics.org/post/41845/, 2 August 2024.

Wulf, Herbert, Indo-Chinese Relations: On a Collision Course, BICC report, August 2024, https://www.bicc.de/Publikationen/20240816_bicc-report_Wulf-online_1.pdf~dr3273

The Author

HERBERT WULF

Herbert Wulf is a Professor of International Relations and former Director of the Bonn International Center for Conflict Studies (BICC). He is presently a Senior Fellow at BICC, an Adjunct Senior Researcher at the Institute for Development and Peace, University of Duisburg/Essen, Germany, and a Research Affiliate at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago, New Zealand. He serves on the Scientific Council of SIPRI.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org