Climate Change and Conflict Report No.198

Sustaining, Nurturing, Shaping: Utilising Conflict Transformation Processes for Overcoming the Climate Crisis

Rebecca Froese, Melanie Hussak, Dani*el*a Pastoors and Jürgen Scheffran

August 06, 2024

Abstract

The interconnectedness of climate change and conflicts is manifold and increasingly being addressed in politics and research. However, there is still little research on the positive connections between sustainable, anti-hegemonic peace and climate justice. Necessary social-ecological transformations are accompanied by conflicts which must be addressed constructively. At the same time, obstacles such as (colonial) structures of domination, power, and inequality must be overcome. In this report [1], we combine climate policy strategies with civil conflict transformation and outline ideas towards shaping a sustained nurturing of the social- ecological transformation.

Contents

- Introduction

- Global power structures and colonial entanglements

- Social-ecological processes and a concept for nurturing social-ecological transformation

- (Conflict) transformation in processes of sustaining, nurturing, and shaping

- Transforming paradigms, structures, and relationships

- Towards viable societies

Introduction

Human-centred development has accelerated since the beginning of European colonial expansion, and today it is increasingly coming up against planetary boundaries. In the so-called Anthropocene[2], the negative effects of climate change, species extinction, and neo-colonial extractivism are becoming ever more apparent. The interplay of growth, power, and violence leads to multiple crises that undermine living conditions, especially for marginalized groups and people in the Global South (Scheffran 1996; 2023). This raises the question of adequate approaches and potentials for action that can contribute to the avoidance of dangerous climate tipping points and violent conflicts and to transforming the hegemonic and anthropocentric structures of human-nature domination towards balanced relationships between nature and society that allow all living beings to enjoy healthy lives on this planet.

In media and public discourses on climate policy and the social-ecological transformation in the Global North, narratives of a (supposed) polarization of societies are evolving: some argue that things are moving too slowly, while others feel left behind. This simplification of existing lines of conflict is not helpful, as it does not reflect the diversity of interests and needs of the actors involved and does not open avenues for the constructive transformation of existing conflicts. We argue that the social-ecological transformation can be constructively shaped, cultivated, and supported through conflict transformation based on sustaining and nurturing processes (Pastoors et al., 2022). Civil conflict transformation, as applied, for example, in the field of conflict-sensitive community work in Germany, tries to overcome the above-mentioned polarization through a focus on process and on needs. This approach invites people to explore and negotiate the intersections for cultivating a solid foundation for society within the planetary boundaries framework (Rockström et al. 2009; Raworth 2017), taking account of different positionalities, interests, and needs.

Central to this approach is a transformation of the understanding of "sustainable development": instead of conceptualizing sustainable development as a linear expansion that inevitably will come up against the limits of growth, it has to be conceptualised as a relational nurturing process that preserves the ecological foundations of life on earth and nurtures the flourishing of human life in balance with the more-than-human nature.[3]

In the following, we discuss how this understanding can be cultivated in spaces of knowledge production and action through civil conflict transformation and climate activism. Further central questions ask how approaches to conflict transformation can be applied not only to social and societal conflicts, but also to social-ecological conflicts and hence can transform nature-society relations. Thus, we ask, how the cultivation of relations with nature can be expanded, which knowledge is recognized, and which assumptions about nature, sustainability, development, and peace come with specific forms of knowledge.

“An analysis of the underlying interconnectedness of violence, power, and domination is a necessary foundation for addressing questions of climate justice and peace.”

Global power structures and colonial entanglements

Countries of the Global South are more affected by the continuous exploitation of resources and the direct effects of the climate crisis than countries of the Global North, which for many decades have been (and in many cases still are) the main sources of emissions and environmental destruction. Linked to this is the destruction of habitats of indigenous peoples through land appropriation, which results from (neo-)colonial processes of domination and produces "epistemically and physically violent hierarchies" (Sumida Huaman and Swentzell 2021, p. 7). Epistemic hierarchies refer to the dominance of knowledge that results from a Eurocentric frame of reference. Its paradigm is based on European modernity, and understands humans as outside of and separate from nature. It poses an obstacle to recognizing different understandings of nature, sustainability, and peace that are grounded in non-European knowledge systems. In this context, knowledge about climate and sustainability is also developed and negotiated in Western-dominated spaces shaped by colonization and coloniality (cf. Krohn 2023). Consequently, local and global efforts to negotiate interests and ensure the participation of marginalized groups in the context of current global climate governance fall short, and scientific and socio-political discourses fail to address colonial continuities. An analysis of the underlying interconnectedness of violence, power, and domination is a necessary foundation for addressing questions of climate justice and peace. As discussed below, this includes not only the reduction of structural inequalities, but also (scientific) knowledge paradigms and relationships between them.

Social-ecological processes and a concept for nurturing social-ecological transformation

While development is usually understood as dynamic and opposite to a static state, "sustainable development" is often used to describe a linear paradigm – as for example in the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Clearly defined goals with sub-goals and measurable indicators serve as reference points, particularly for Western societies, to determine and disclose results of implementation. The consensual formulation of goals is perceived as helpful in negotiations with global players and in setting a shared direction and pace. However, the decision-makers fail to consider who is actually involved in formulating such goals and which groups are systematically excluded from these processes.

Critical comments by decolonial and indigenous authors point to the limits of central concepts such as "sustainable development", which “is human-centric, referencing a quality of life that demands economic, social, and environmental resources in perpetuity” (Sumida Huaman and Swentzell 2021, p. 9) and, due to the hegemonic paradigm, is based on "delusional assumptions of infinite growth" (Vásquez-Fernández and Ahenakew pii tai poo taa 2020, p. 66) and (re)produces patterns of exploitation (ibid, p. 65). In contrast, these critics advocate for equivalence and balance between humans and more-than-human nature, and for the sustaining of indigenous traditional knowledge within communities and between generations (Sumida Huaman and Swentzell 2021, p. 10).

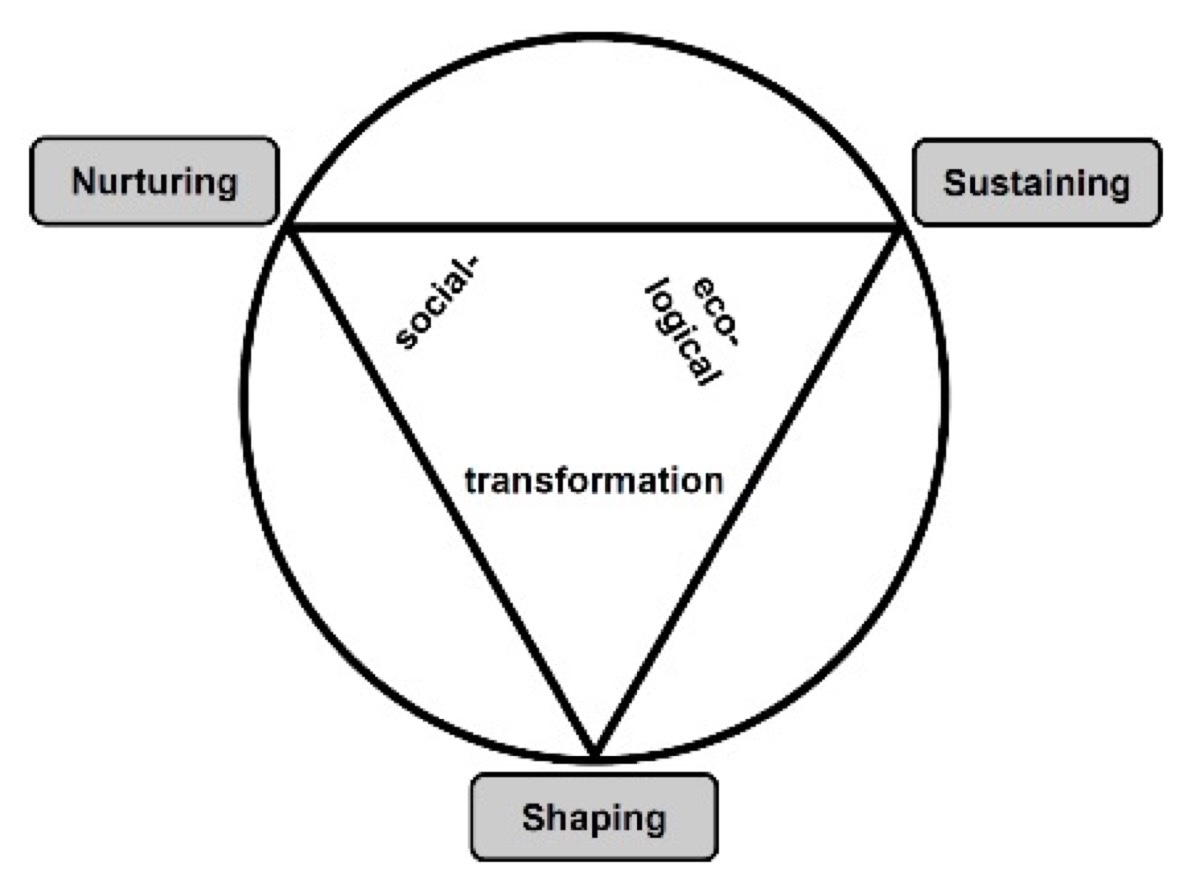

Although this critique also defines goals, the questions regarding "how", i.e. the processes for achieving the goals, differ significantly. from the pursued hegemonic sustainable development discourse. Regarding the ability to pursue viable pathways, the perspective shifts from the goals to the processes, and linear thinking gives way to circular thinking. In the following, we will focus on this circularity and process orientation (see Figure 1). The three corners of the triangle each show a central process of the social-ecological transformation.

Figure 1: Sustaining, Nurturing, Shaping: Three key processes of social-ecological transformation.

The process of ‘sustaining’ focuses on what is to be preserved as a necessary living condition and reflects first the ecological dimension. Sustaining the natural foundations of life and respecting planetary boundaries are essential for life to exist. It is also about the value of life as such that requires the preservation of biodiversity. In this context, it is necessary to overcome modern paradigms such as the human-nature dichotomy, and recognize that humans themselves are nature and part of the ecological systems, that the human species is connected to all life on the planet, and that all living beings are interrelated (Kothari et al. 2014). More broadly, it is also about securing human lives and livelihoods that are threatened, restricted, and destroyed by structurally violent human systems of domination.

Beyond mere survival and beyond the protection of the existing state of things, the goal is to enable the flourishing of life in such a way that its sustainability is not jeopardized. In the sense of "Buen Vivir" (Kothari et al. 2014), a good life for all, the flourishing processes in the social dimension strive for freedom and justice for all people and living beings that are in a non-destructive balance with each other. The human flourishing processes focus primarily on the social systems without neglecting the guiding principle and awareness of the underlying human-nature relationship and the principle that social and ecological processes cannot be separated from one another (Drees et al., 2021).

(Conflict) transformation in processes of sustaining, nurturing, and shaping

The challenge is to actively and constructively cultivate the processes of a sustaining and nurturing social- ecological transformation. A concept of peace-promoting social-ecological transformation would require that existing structures be questioned and, if necessary, dismantled and transformed into new forms that have yet to be negotiated. Such processes of change must also take into account the constructive handling of inherent conflicts. Shaping is thus the third process; it encompasses the dimension of (conflict) transformation towards sustainable, power-critical, and relational peaces (the plural form of “peace” is used intentionally here).

For example, what is considered "worth sustaining" in the sense of preservation or conservation or what exactly can, may, and should be nourished, must be understood as the subject of social negotiation processes conducted in a power-critical and power-sensitive manner. These negotiation processes also put up for discussion hegemonic discourses, such as conventional sustainability concepts with their reduction to social, ecological, and economic aspects. They invite expansion—for example, into political, identity, and spiritual dimensions—as well as the discussion of alternative concepts.

On the one hand, the greatest challenge of this cultivating process is to recognize the complexity of this undertaking. It would need to come without prematurely pointing to supposedly simple solutions that make change seem achievable and acceptable only in the short term but which harbour a certain potential for conflict in the longer term. On the other hand, it is also important to be aware of the danger of inaction – a feeling of powerlessness that leads to the inability to act in the face of perceived extreme complexity and conflict that contributes to perpetuating a structurally violent status quo.

In shaping sustained nurturing processes, it is therefore essential to overcome the structural violence of global and local power relations and colonial entanglements and to work on them through conflict transformation, to shape and cultivate relationships on an equal footing and "to harmonize the satisfaction of the needs of the human species with the needs of continued life on earth" (Pastoors et al. 2022, p. 299). Looking at these conflicts, needs, strategies, and relationships, the importance of peace and conflict work in social-ecological transformation processes becomes clear. Civil conflict transformation opens up ways of transforming impasses in political and social discourses by addressing the underlying structures of the climate crisis and thus integrating not only the symptoms of the climate crisis but also its multi-layered roots into the negotiation processes.

Transforming paradigms, structures, and relationships

The importance of conflict transformation in social-ecological transformation processes is reflected in different conceptions of peace and the underlying paradigms. Many indigenous groups include the relationship to nature in their ideas and perceptions of peace, for example, the Hawaiian "Ho'oponopono" (Walker 2004, p. 534f.). Peace is understood as processual and relational and is thoroughly contextualized by different experiences, lifeworlds, and linkages to place. Relationality can include relationships between very different entities: those between different people, between humans and their environment, and also those between living beings and non-living elements of the planet. Despite different concepts and ways of living peace, there are commonalities of indigenous conceptualisations of peace, such as a focus on restoration of relationships, and the orientation towards a living cosmos (Brigg and Walker 2016, p. 260). Shaping and nurturing social- ecological transformation includes relational thinking about space and place (Brigg 2020, p. 549), as well as respectful recognition of the equivalent interconnectedness with all living beings (Vásquez-Fernández and Ahenakew pii tai poo taa 2020, p. 65). [4]

How can nurturing processes be sustained and shaped in conflict transformative ways? For instance, they can initiate collective action, consciously break down structures of dominance, cultivate relationships, and open up spaces for exchange between people who hold different knowledge systems – which is a fundamental element of conflict transformation.

“Only if the interdependence of all life is taken seriously, the processes of sustaining, nurturing, and shaping, embedded in the framework of social- ecological transformation, can lead to sustainable, peaceful relations. ”

Such an understanding across different knowledge systems also has the potential to overcome the barriers of silo thinking and sectoral action – and to look at problems from different perspectives (see Berg 2020). We are, therefore, primarily concerned with broadening perspectives and raising awareness and recognition of the aspects mentioned. In practice, this can be done in so-called decentralized spaces, where many small transformations can take place. Such spaces could be:

- physical spaces that enable negotiation processes, co-production of knowledge, and transdisciplinary dialogues (e.g. district cultural centres and neighborhood meetings in conflict-sensitive community work), or

- networking events for different societal groups to exchange knowledge and resources and to strengthen political participation, as well as

- "playgrounds" for testing new formats of transformative processes (e.g., real-world laboratories).

The structures of domination and hegemonic forms of knowledge criticized here cannot be dismantled and transformed through false interpretations and appropriations of decolonial and power-critical concepts by Western European actors. Rather, negotiation processes in decentralized spaces must also be expanded at the level of actors and decision-makers and allow space for diverse perspectives and positionalities. As long as this relevance of decentralized and enabling structures is not taken into account and as long as they are not developed further, the narrative of the "Great Transformation" will remain an illusion, as will the narrative of sustainable peace (Brauch et al. 2016).

Towards viable societies

There is a need to turn away from existing expansive development models, which in their colonial and imperial variants have extended the model of domination emanating from Europe to the entire planet and have led to the separation of the biosphere and the sociosphere through globalization. The enforced rupture of relationships with the more-than-human nature and one's own land/place is one of the most profound aspects of colonial processes for the colonized (Walker 2004, p. 530). Only if the interdependence of all life is taken seriously, the processes of sustaining, nurturing, and shaping, embedded in the framework of social- ecological transformation, can lead to sustainable, peaceful relations.

A decolonial perspective draws attention to the epistemic and ontological forms of violence of dominant scientific discourses (ibid., p. 527), which contribute to the maintenance of colonial relations of domination and power and have so far made it impossible to take this interdependence seriously. For social-ecological transformation processes that are critical of domination, it is therefore essential to question the epistemic, ontological, methodological, and ethical foundations of the hegemonic discourse and to recognize indigenous, traditional, and other non-Western knowledge systems as equally valid.

For transformation efforts towards greater climate justice, this means that global and colonial power structures must be dismantled. Conflict transformation that sets itself the task of thinking in terms of multiple peaces as social-ecological transformation processes and of supporting climate justice, requires the willingness to include different ways of knowing and positionalities and to recognize counter-hegemonic perspectives of knowledge and action as the starting point for further considerations. The "composting" of the world's colonial legacy and hegemonic knowledge system (Or 2023) is a prerequisite for a regenerative society that sustains and nurtures life. Stepping back, listening, and unlearning (ibid.) are essential components of conflict work and transformation processes and thus central to the concept of a nurturing social-ecological transformation and hence the creation of viable societies.

References

Berg, C. (2020): Ist Nachhaltigkeit utopisch? Wie wir Barrieren überwinden und zukunftsfähig handeln. München: Oekom Verlag.

Brauch, H. G.; Oswald Spring, Ú.; Grin, J.; Scheffran, J. (2016): Handbook on sustainability transition and sustainable peace. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Brigg, M. (2020): The spatial-relational challenge: Emplacing the spatial turn in peace and conflict studies. Cooperation and Conflict 55 (4), pp. 535-552.

Brigg, M.; Walker, P. O. (2016): Indigeneity and peace. In: Richmond, O.P.; Pogodda, S. und Ramović, J. (Hrsg.): The Palgrave handbook of disciplinary and regional approaches to peace. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 259-271.

Crutzen, P. J. (2002): Geology of mankind. Nature 415, p. 23.

Drees, L.; Lütkemeier, R.; Kerber, H. (2021): Necessary or oversimplification? On the strengths and limitations of current assessments to integrate social dimensions in planetary boundaries. Ecological Indicators 22(129), 108009.

Kothari, A.; Demaria, F.; Acosta, A. (2014): Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy. Development 57(3-4), pp. 362-365.

Krohn, J. (2023): (K)Ein Frieden mit der »Natur«? Zum anthropozentrischen Frieden der kolonialen Moderne. W&F 2/2023, pp. 14-16.

Or, Y. (Hrsg.) (2023): Praxisbuch Transformation dekolonisieren. Ökosozialer Wandel in der sozialen und pädagogischen Praxis. Weinheim: Beltz.

Pastoors, D.; Drees, L.; Fickel, T.; Scheffran, J. (2022): „Frieden verbessert das Klima“ – Zivile Konfliktbearbeitung als Beitrag zur sozial-ökologischen Transformation. Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik 15, pp. 283–305.

Raworth, K. (2017): A doughnut for the Anthropocene: humanity’s compass in the 21st century. The Lancet Planetary Health 1(2), e48-e49.

Rockström, J. et al. (2009): A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461, pp. 472-475.

Scheffran, J. (1996): Leben bewahren gegen Wachstum, Macht, Gewalt: Zur Verknüpfung von Frieden und nachhaltiger Entwicklung. W&F 3/1996, pp. 5-9.

Scheffran, J. (2023): Limits to the Anthropocene: geopolitical conflict or cooperative governance? Frontiers of Political Science 5, 1190610.

Simmons, K. (2019 [post print]): Reorientations; or, An indigenous feminist reflection on the Anthropocene. JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58 (2), pp. 174-179.

Sumida Huaman, E.; Swentzell (2021): Indigenous education and sustainable development: Rethinking environment through indigenous knowledges and generative environmental pedagogies. Journal of American Indian Education 60(1-2), pp. 7-28.

Vásquez-Fernández, A. M.; Ahenakew pii tai poo taa, C. (2020): Resurgence of relationality: reflections on decolonizing and indigenizing ‘sustainable development’. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 43, pp. 65-70.

Walker, P. O. (2004): Decolonizing conflict resolution: Addressing the ontological violence of Westernization. The American Indian Quarterly 28(3), pp. 527-549.

NOTES

[1] This report is a translation of a German language article by the four authors: Froese R, Hussak M, Pastoors D, Scheffran J (2023) Erhalten, Entfalten, Gestalten - Mittel der Konflikttransformation für Wege aus der Klimakrise einsetzen. Wissenschaft und Frieden 2023/4, 43–47. There is no obvious and exact translation of the key terms of the title, which in English have multiple different meanings: Erhalten (sustain, protect, preserve, uphold, nourish), Entfalten (develop, evolve, flourish, nurture, unfold), Gestalten (shape, cultivate, conform, configure, design, enable, facilitate). The authors have therefore chosen the English translation “Sustaining, Nurturing, Shaping”, borrowed from ecosystem science to highlight the relational approach to human-nature interactions, which forms the basis for this article.

[2] The concept of the Anthropocene was proposed by Paul Crutzen at the beginning of the 21st century in order to capture a fundamentally new period in history in which human-induced planetary changes define a new geological age, in particular, the increase in CO2 levels in the atmosphere due to its effects on a global scale (see Crutzen 2022). The concept has already been widely criticized, especially by authors from the Global South and indigenous authors, as the narrative of shared vulnerability speaks of a homogeneous global society and thus does not raise the questions of responsibilities for the changes and of injustices, ignoring the importance of different economic systems and their interdependencies in (neo-)colonial power structures (cf. Simmons 2019).

[3] The term "more-than-human" nature points to the fact that humans are part of nature, at the same time making clear that nature beyond the human species is under consideration. The term questions anthropocentrism and the dichotomy between humans and nature; instead it focuses on the interdependent relationships of intertwined life.

[4] The anthropocentric perspective of European modernity, which sees humans at the centre of the world and nature as an object of domination and is based on the separation and hierarchisation between humans, other living beings and nature, has to be questioned. Instead, in line with indigenous concepts, the so-called "environment" is not conceptualised as separate, but rather holistically/cosmologically, with humans connected to all others elements of nature, as an equal species among others (Vásquez- Fernández and Ahenakew pii tai poo taa 2020).

The Author

REBECCA FROESE

Rebecca Froese focuses on social engagement for social-ecological transformation, embedded in larger questions of justice, social cohesion, democracy, and conflict transformation. One of her current projects at the Center of Interdisciplinary Sustainability Research (ZIN) in Münster, Germany, and the Research Institute for Sustainability (RIFS), Potsdam, focuses on conflicts and violent structures in societies coping with polycrisis, with a particular focus on land conflicts; another explores artistic methods for creating spaces for dialogue for conflict transformation in the context of social-ecological transformation. Dr. Froese completed her Ph.D. at the intersection of peace and conflict studies and environmental sciences on social cohesion, land conflicts, and social-ecological tipping points in the southwestern Amazon. She studied Integrated Climate System Sciences and Geosciences in Hamburg, Germany, Victoria (Canada), and Bremen, Germany.

MELANIE HUSSAK

Melanie Hussak is a postdoctoral researcher at the Peace Institute Freiburg at the Pr. University of Applied Sciences, where she is engaged in research, lecturing in the MA Peace Education and in third mission activities. From 2022 to 2023 she was a research associate at the University of Haifa and from 2015 to 2022 at the Peace Academy Rhineland-Palatinate/RPTU. In 2015, she was a fellow at the Austrian Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution. Dr. Hussak studied political science and economics at the University of Vienna and completed a postgraduate degree in “Interdisciplinary Conflict Analysis and Conflict Transformation” at the University of Basel. She completed her Ph.D. at RPTU on peace conceptions and peace initiatives of indigenous communities in the context of colonization and ongoing coloniality.

DANI*EL*A PASTOORS

Dani*el*a Pastoors is research associate at the Center for Interdisciplinary Sustainability Research (ZIN) at the University o fMünster, and responsible for building up an innovation hub on socio-ecological sustainability in the region of Münsterland and within an European University Alliance Network (Ulysseus). Dr Pastoors researches and teaches at the interface of elicitive conflict transformation approaches, regenerative peacebuilding and socio-ecological transformation, studied peace and conflict research in Marburg and completed their doctorate on the question of how peace workers in the Civil Peace Service receive psychosocial support. They worked in different NGOs regarding peace education and nonviolence movements, human rights observation on indigenous land rights and are passionate about theater of liberation and nonviolent communication.

JÜRGEN SCHEFFRAN

Jürgen Scheffran is Professor of Integrative Geography (em.) at the University of Hamburg, and since 2009 Chair of the Research Group Climate Change and Security (CLISEC) in the Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability and the Climate Excellence Cluster CLICCS. After study and his doctorate in physics, he worked in interdisciplinary groups in environmental, security and conflict research at the universities of Marburg, Darmstadt, Paris and Illinois, as well as the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). In addition to networking activities and editorial work on science and peace, Dr. Scheffran has been involved in projects for the United Nations, the Office of Technology Assessment of the German Parliament, and in the Expert Commission on the Causes of Forced Migration of the German government.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org