Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament Report No.197

Filling the Gap: How the Human Rights Pillar is Helping Curb Weapons-Related Harm

Hine-Wai Loose and Florence Foster

January 01, 1970

The report addresses what has worked and what is the way forward for the disarmament machinery, when faced with the grim reality that it has been and continues to be undermined by geo-political and economic agendas. For the diplomat or advocate wanting to see progress on disarmament and arms control at this moment, what can be done? Are there routes around the rule of consensus? How can we refocus on protecting civilians and ensure that work in multilateral fora does not replicate a debating society, but instead has an impact on the ground?

Contents

- Introduction

- Social-ecological processes and a concept for nurturing social-ecological transformation

- Enhanced and holistic understanding of impacts

- A holistic understanding of “responsibility” and complementary processes

Introduction

In depicting the dire state of global security, the UN Secretary-General’s New Agenda for Peace [1] calls for a human-centred approach to disarmament. If heeded, this call should prompt the arms control and disarmament community to step back and reflect on how things could work differently.

Indeed, the landscape of global security has experienced profound shifts, necessitating a comprehensive reassessment of the multilateral arms control and disarmament machinery (henceforth ‘disarmament machinery’). Established in the aftermath of devastating world wars with a renewed push after the end of the Cold War, many of these mechanisms that aimed at curbing arms proliferation and thereby promoting international peace now require critical re-examination.

Since 1996 the Conference on Disarmament (CD) has been deadlocked. The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty has not yet entered into force and instead has faced further challenges with the Russian Federation withdrawing its ratification in 2023. Furthermore, small arms and light weapons—that each and every day take lives, remain the weapon of choice in organized crime and are used in perpetuating gender-based violence— have only been subject to limited restrictions.

The grim reality is that the disarmament machinery has been and continues to be undermined by geo-political and economic agendas. It also frequently does not prioritize the fundamental rights and promote the safety of those it is meant to protect, namely the individuals and communities impacted by weapons and caught in the cross-hairs of arms conflicts or armed violence. Coupled with this is the inability of these multilateral processes to overcome the barriers posed by the rule of consensus or the inadequate lowest common denominator approach to negotiations. Keeping pace with the human dimension of fast-changing technological advancements in warfare also is increasingly challenging.

So, what has worked and what is the way forward? In other words, for the diplomat or advocate wanting to see progress on disarmament and arms control at this moment, what can be done? Are there routes around the rule of consensus? How can we refocus on protecting civilians and ensure that work in multilateral fora does not replicate a debating society, but instead has an impact on the ground?

“The grim reality is that the disarmament machinery has been and continues to be undermined by geo-political and economic agendas.”

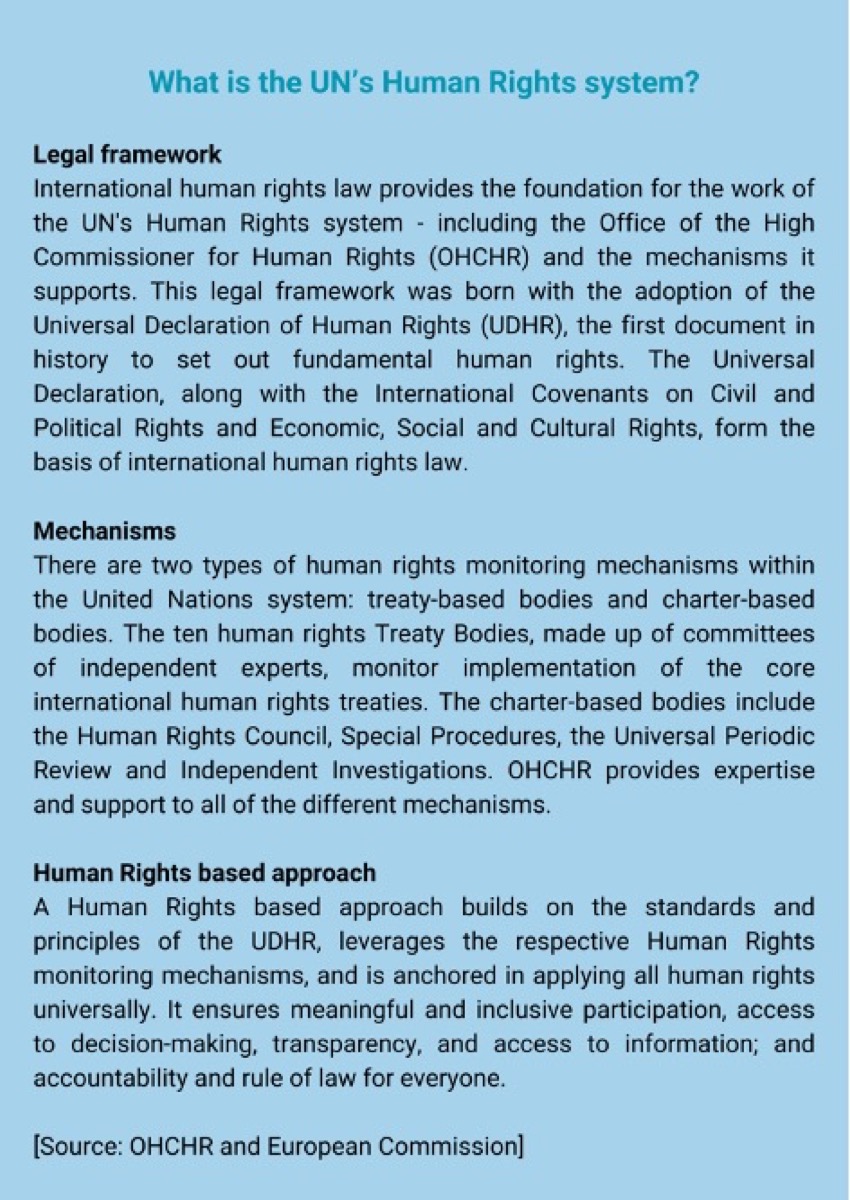

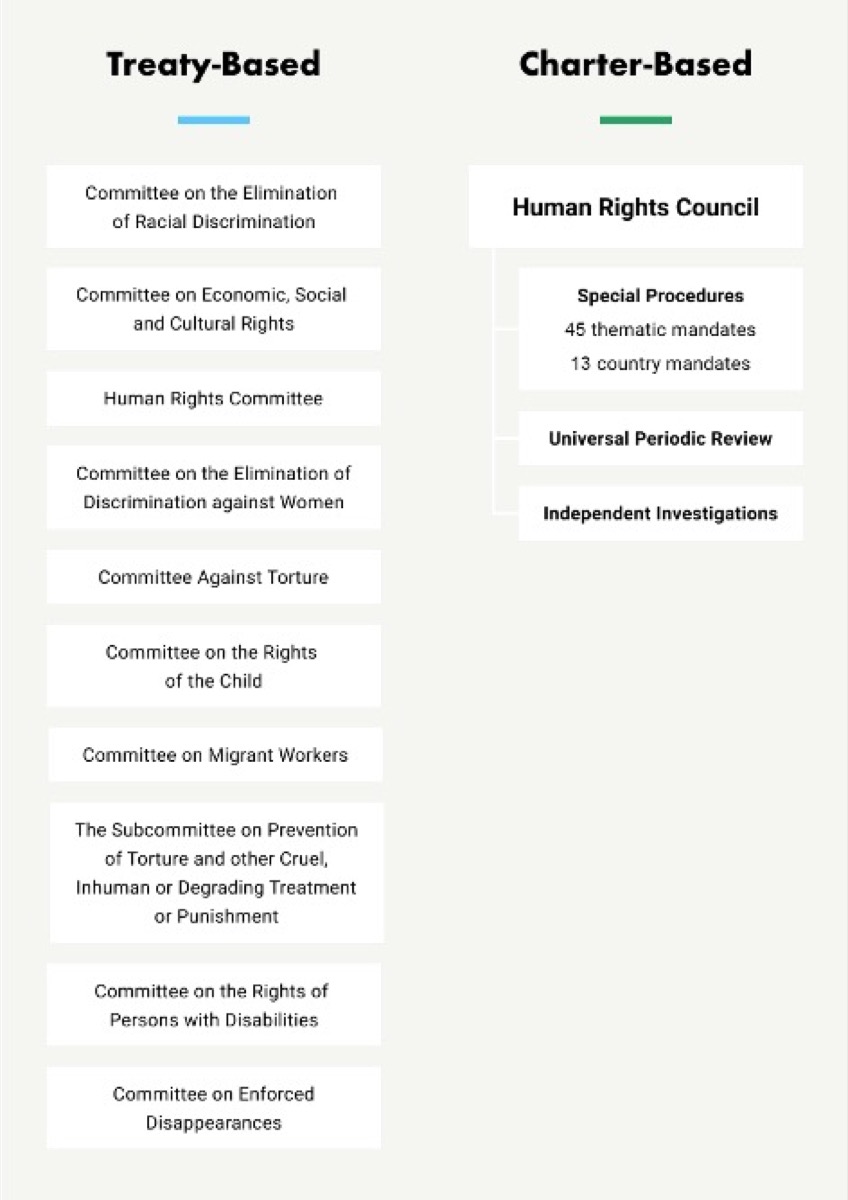

One promising avenue in response to this blocked environment is the use of the United Nations Human Rights system (see Table 1 ‘The UN's Human Rights System and a human rights-based approach explained’). This article will explore how, by approaching the topic from a different vantage point and seeking to leverage complementary parts of the United Nations system, progress has been made, State and business accountability enhanced and a more holistic understanding of arms-related risks ensured. While some disarmament and arms control treaties have undoubtedly had a real impact, [2] this article will focus on how some actors have taken a different approach to prioritize the prevention and remediation of human suffering and environmental harm.

Table 1 The UN's Human Rights System and a human rights based approach explained

Social-ecological processes and a concept for nurturing social-ecological transformation

A major challenge in the disarmament machinery is the prevalence of the rule of consensus, which has undermined progress and the ability of discussions to address States’ duties, let alone the hope to establish new narratives through dialogue and negotiation.[3] In comparison, at the Human Rights Council (HRC), a multilateral forum untouched by the veto-mentality where voting is allowed and where all States have a prerogative to put forward initiatives, progress continues. Normative developments in the form of country specific or thematic resolutions are negotiated on new and emerging issues at a solid pace. Whether adopted by consensus or with a vote, or rejected, momentum continues through inclusive negotiations and inputs from States and civil society. Despite political push back against including arms-related matters in the HRC’s portfolio, resolutions on arms transfers and firearms acquisitions by civilians have evolved to be household resolutions, focusing on different thematic areas over the past decade and expanding our collective understanding of the harmful impacts of recourse to weapons.[4]

Gradually, throughout the Human Rights system—in country specific resolutions, pursuant reports, Special Procedures, investigative mechanisms or through Treaty Bodies committees—the impact of weapons on human rights is being addressed. The system’s analysis and recommendations are based on international human rights law, founded on the UDHR and IHL, thus providing a more universally applicable normative imperative and helping to circumvent and fill the gap of the often irregular uptake of legally binding instruments in the disarmament machinery.

The value of the Human Rights system lies in the universality of rights covered as well as States covered, enabling all States to be held accountable for their obligations in various complementary fora and providing a more level playing field between them. The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is a particular case in point as a peer review process covering all rights.[5] It has recently been used as a space to encourage States to join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) or strengthen the national regulation on small arms acquisition by civilians.[6] Some States have subsequently committed to implementing these peer recommendations.[7]

“human rights mechanisms’ recommendations provide a roadmap for implementation”

The HRC’s Special Procedures,[8] independent human rights experts with country or thematic mandates to report and advise on human rights, are arguably not under the same political pressure as other institutions, and therefore have more freedom to speak out on a range of issues. For example in February 2024, a group of Special Procedures experts spoke out on transfers to Israel that would be used in Gaza, referring to the likelihood that weapons, ammunition and their parts and components were being used to violate international humanitarian law (IHL) and human rights in violation of Common Article 1 of the Geneva Convention, the ATT, and EU arms export control law.[9] The Special Rapporteur on Myanmar has also been explicitly damning of arms transfers to the Myanmar military, which has been accused of bombing civilian populations in violation of IHL.[10] Other similar investigative mechanisms of the HRC have questioned the legality of arms transfers and in doing so have referred to Common Article 1 and the Arms Trade Treaty.[11] Such public and critical assessments would be highly unlikely to be made by the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) or other parts of the disarmament machinery.

Additionally, deliberations at the HRC are designed to include civil society, enabling those concerned with the human impact of weapons to access State representatives and share their concerns with a broad audience, including UN Agencies and other like-minded civil society actors. Most significantly, human rights mechanisms’ recommendations provide a roadmap for implementation and are often used for national advocacy by civil society, for example in litigation at the national level, or as a better entry point for parliamentarians to ensure implementation through national mechanisms. In 2016, for instance, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) requested the Government of Switzerland to “monitor the impact of the misuse and illicit trade of small arms and light weapons on women, including those living in conflict zones, and ensure that arms-producing corporations monitor and report on the use of their arms in violence against women” to ensure compliance with Article 7(4) of the ATT, as well as to conduct an independent study to “analyze the link between the uncontrolled possession of arms by men in the State party and the impact on gender-based violence against women and girls”.[12][13] This resulted in several parliamentary motions to that effect.

The disarmament machinery often lacks such inclusive pathways to enable progress, review States’ implementation and enhance their accountability; in some fora, what space did exist has recently become more restricted.[14] Through its component parts, the Human Rights system has come some way to fill these gaps within its particular purview.

Enhanced and holistic understanding of impacts

Over the past decade, OHCHR has been producing reports pursuant to the above-mentioned HRC resolutions on international arms transfers and firearms acquisitions by civilians. These focus on the economic, social and cultural impacts; highlighting the negative repercussions for women and girls, youth and children; and shedding light on corporate responsibility in the arms sector, among other issues.[15] These reports have consolidated and brought to the fore in detail a human-centred and intersectional analysis of arms-related impacts. OHCHR’s 2023 report on firearms acquisitions focused on business enterprises and states, stating “[firearms] affect communities based on their socioeconomic status, often disproportionately affecting racial and ethnic minorities. There is also a significant gender dimension to firearms deaths and injuries.”[16] That same report goes on to describe the challenges posed by the United States of America’s arms industry where it sets out that, “[I]n the United States, the firearms industry lobbied for the so-called Tiahrt amendments, preventing the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives from effectively investigating compliance by the industry with firearms legislation.”[17] It is difficult to imagine such reporting being provided elsewhere within the UN system. These HRC mandated reports have provided recommendations, making reference when appropriate to corresponding parts of the disarmament machinery.

In describing how a range of conventional weapons and weapons of mass destruction affect the Right to Life, the Human Rights Committee—the body that monitors implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights—stated specifically on nuclear weapons that, “[t]he threat or use of weapons of mass destruction, in particular nuclear weapons, [...] is incompatible with respect for the right to life and may amount to a crime under international law.”[18] They continue by emphasizing that States, including nuclear-possessing States, must “pursue in good faith negotiations in order to achieve the aim of nuclear disarmament under strict and effective international control, and to afford adequate reparation to victims [...]”[19] in order to protect the right to life. At a time when some nuclear-armed States have threatened to use nuclear weapons, the Human Rights Committee’s statement on nuclear weapons complements the TPNW and crucially reaffirms that the threat or use of these weapons contravenes international law.

“there is widespread concern that allowing LARs [lethal autonomous robotics] to kill people may denigrate the value of life itself.”

The HRC has acknowledged and addressed the multifaceted societal and environmental fall out of weapons by providing alternative pathways for countries to seek technical assistance where the disarmament machinery has not. With respect to nuclear weapons, for example, the Marshall Islands tabled a resolution in 2022 seeking technical assistance in order to more adequately address its nuclear legacy. In passing the resolution, the HRC acknowledged the lasting threats posed by nuclear waste, radiation, and contamination to Marshallese and their environment, and the need to address this as a matter of right.[20]

The military application of autonomous technologies was first introduced to the UN via the HRC —not within the disarmament machinery—as a human rights concern sensitive to the broad socio-political, humanitarian, and ethical challenges that new technologies pose. In his 2013 report, the then Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions expressed the concern that, “there is widespread concern that allowing LARs [lethal autonomous robotics] to kill people may denigrate the value of life itself.”[21] While this issue was then taken up at the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) and since 2023 at the General Assembly, it has returned to the HRC. Specifically, HRC’s Advisory Committee—whose independent and cross-regional experts function as a think-tank for the HRC—is currently working on a report focusing on human rights implications of new and emerging technologies in the military domain (NTMD).[22] By taking up this issue at the HRC, States and civil society can draw attention to the disastrous socio-political, humanitarian, and ethical challenges of NTMD – including but not limited to software, sensors, algorithms, and artificial intelligence. Particularly, there is hope that it could galvanize political momentum towards a new international treaty on lethal autonomous weapons.

This holistic understanding of how weapons affect individuals, communities and regions can serve to identify worrying trends around weapons use and acquisition that could further exacerbate tensions or conflict. For example, following his country visit to Brazil, the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, warned about the recently adopted legislation that facilitates access to guns and ammunition. His concern focused particularly on the risks of possible armed or violent interference during the then upcoming 2022 election processes [23] in light of an already polarized campaign and levels of political violence in the country.

By fostering a comprehensive understanding of the impact of different weapons systems and outlining their impact on human rights, work at the Human Rights system underscores the critical need for disarmament and arms control obligations to be respected and the urgency of addressing the true human cost of non- compliance.

A holistic understanding of “responsibility” and complementary processes

Processes that take an intersectional and human-centred analysis are more likely to provide outputs that address the diverse range of impacts as well as the diverse range of stakeholders that bear responsibility for (potential) harm.

The Human Rights system has led the way in making the connection between the private sector and its impact on and responsibilities concerning human rights. Adopted by consensus over a decade ago at the HRC, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) represent the global standards for preventing and addressing the risk of adverse impacts on human rights linked to business activity. In particular, they outline the responsibilities of companies in relation to international human rights law, and emphasize that, in situations of armed conflict, companies must also respect IHL. Most recently, the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights (UNWG)—a group of independent human rights experts mandated to promote, disseminate and implement the UNGPs—published an Information Note [24] (hereafter ‘Note’) on so-called responsible business conduct in the arms sector in 2022. This was in response to the arms industry’s reluctance to acknowledge their own human rights responsibilities and States’ unwillingness or inability to restrain harmful behaviour. The Note outlines States’ responsibility as licensors of arms transfers, often as end-users or else regulators of how weapons are acquired. Most significantly, it also establishes that the full set of private actors linked to the arms industry plays a pivotal role in assessing and preventing harm. Through ongoing and thorough assessments in line with the UNGPs, using Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD) processes, companies may conclude that they need to go beyond national laws and regulations in the relevant jurisdiction to prevent harm and potentially refrain from engaging in business, which otherwise would have been permitted.

Several HRC-mandated reports subsequently make reference to the Note [25] or the UNGPs [26] directly when discussing arms-related harms, emphasizing that both States and private actors have human rights duties and responsibilities respectively. Building on these developments and under the thematic umbrella of ‘The Role of Industry in Responsible International Transfers of Conventional Arms’,[27] States brought forward these normative developments into the ATT 9th Conference of States Parties (CSP) [28] in 2023.

The decisions agreed in the Final Report [29] to welcome the UNGPs and encouraged “States Parties and other stakeholders to continue discussions on how the UNGP, Human Rights and IHL instruments apply in the context of the Arms Trade Treaty”. This decision has the potential to contribute to developing a better understanding of the ATT’s human rights dimensions, the actors involved in arms transfers, and the subsequent steps necessary to prevent and remediate harm. Ongoing discussions at CSP10, notably under the Working Group on Effective Treaty Implementation (WGETI),[30] continue this important work. Such cross fertilization between the ATT and HRC was essential to underlining the responsibilities of industry and how human rights approaches can contribute to what is strictly an arms control forum. If it is to be effective, the disarmament machinery cannot afford to operate in silos and instead must be open to similar cooperation [31] and sharing of information.

Over the last decade, various approaches have been explored to counter the grim reality of arms control and disarmament frameworks that continue to be state-centric and undermined by geo-political and economic agendas. The above examples demonstrate how actors have leveraged the human rights system to ensure human rights remain central to decision making and advocacy relating to arms control and disarmament. These also illustrate the possibility of meaningfully addressing the responsibilities of both States and companies, offering prospects of energizing the disarmament machinery.

The human rights system cannot alone do what the arms control and disarmament frameworks were set up to do, not least as it finds itself already strained with ever shrinking budgets. Nevertheless, there are lessons to be drawn from the human rights system; in the words of the UN Secretary General, it challenges us all to consider ‘networked multilateralism’ as a necessary way forward. One that looks at what the system as a whole can do with its constituent parts working together to deliver on its promises “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”.

Looking ahead and beyond the 2024 Summit of the Future, the disarmament machinery will need to show creativity and adaptability if it is to have a meaningful impact and make a real contribution to peace and security.

Notes

[1] Guterres, Antonio. “Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 9: A New Agenda for Peace.” United Nations: July 2023.

[2] Examples of progressive disarmament and arms control regimes include the 1997 Convention on Anti-Personnel Landmine; 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions: 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons These treaties are considered to be leading examples of a humanitarian approach to disarmament and include provisions to both remedy harm to and protect civilians. A recent publication by Rosa-Luxemburg Stiftung builds on these developments to cast opportunities and possibilities for arms control and disarmament fora.

[3] The rule of consensus has been frequently put forward as a necessity to ensure major military powers engage and endorse a new instrument, claiming that without them it would be unsuccessful. However, it is the rule of consensus that has prevented the CD from agreeing a programme of work, let alone getting down to constructive negotiations on disarmament or holding themselves accountable for those items already agreed upon. It is the rule of consensus that prevented agreement on the final report at the 2023 review conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and it is this same rule that allows the High Contracting Parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) to take a “go slow” approach to addressing increasing concerns at the development of lethal autonomous weapons systems.

[4] HRC resolutions on ‘Human rights and the regulation of civilian acquisition, possession and use of firearms’ A/HRC/RES/26/16 (2014), A/HRC/RES/29/10 (2015), A/HRC/RES/38/10 (2018), A/HRC/RES/45/13 (2020) A/HRC/RES/50/12(2022), A/HRC/56/L.9 (2024); and on ‘Impact of arms transfers on human rights’ A/HRC/RES/24/35 (2013), A/HRC/RES/32/12 (2016), A/HRC/RES/41/20 (2019), A/HRC/RES/47/17 (2021), A/HRC/RES/53/15 (2023)

[5] The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is a mechanism of the Human Rights Council that calls for each UN Member State to undergo a peer review of its human rights records every 4.5 years. The UPR provides each State the opportunity to (1) regularly report on the actions it has taken to improve the human rights situations in said country and to overcome challenges to the enjoyment of human rights; and (2) receive recommendations for continuous improvement from UN Member States – informed by multi-stakeholder input and pre-session. For more: https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr- bodies/upr/upr-home

[6] E.g. Peru to Angola (Supported Rec.146.86, 2019) ‘Strengthen norms that regulate the use, possession and acquisition of small arms, in particular with a view to reducing the number of weapons illegally possessed’ Ecuador to Italy (Noted Rec.148.7, 2019) ‘Sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, and integrate a human rights impact assessment into its arms export control mechanisms’ for more see UPR Info database (search term ‘arms’ as an example).

[7] E.g. Namibia to Italy (Supported Rec. 148.232, 2019) ‘Take more measures to prevent arms transfers that may facilitate human rights violations, including gender-based violence, and that negatively impact women’.

[8] The special procedures of the Human Rights Council are independent non-paid human rights experts who are elected for 3-year mandates (renewable once) with mandates to report and advise on human rights from a thematic or country-specific perspective. They undertake country visits, act on individual cases of reported violations and concerns of a broader nature by sending communications to States and others, contribute to the development of international human rights standards, and engage in advocacy, raise public awareness, and provide advice for technical cooperation – with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). For more: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures- human-rights-council

[9] Ben Saul, Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism; Margaret Satterthwaite, Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers; [...], ‘Arms exports to Israel must stop immediately : UN experts’, 23 February 2024.

[10] ‘Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, ‘The Billion Dollar Death Trade: The International Arms Networks that Enable Human Rights Violations in Myanmar’, May 2023.

[11] See for examples: Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar on the International The economic interests of the Myanmar military,2019. UN Human Rights Council ‘Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014: Report of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts as submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, 9 August 2019, A/HRC/42/17, para 96.

[12] Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women reviews the reports of Switzerland, 02 November 2016.

[13] Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, ‘Concluding observations on the combined fourth and fifth periodic reports of Switzerland’, 18 November 2016, para 17 and 27.

[14] See Laura Varella and Ray Acheson, “CCW Operates in the Dark for Lowest Common Denominator Outcomes”, 20 November 2023.

[15] See OHCHR Reports on ‘Human rights and the regulation of civilian acquisition, possession and use of firearms’ A/HRC/32/21 (2016), A/HRC/42/21 (2018), A/HRC/49/41 (2022), A/HRC/53/49 (2023); and on ‘Impact of arms transfers on human rights’ A/HRC/35/8 (2017), A/HRC/44/29 (2020), A/HRC/51/15 (2022), A/HRC/56/42 (2024).

[16] A/HRC/53/49, 5 May 2023, para 10.

[17] Ibid, para 51.

[18] CCPR/C/GC/36, 3 September 2019, para 66.

[19] Ibid, para 66.

[20] HRC resolutions on ‘Technical assistance and capacity building to address the human rights implications of the nuclear legacy in the Marshall Islands’ A/HRC/RES/51/35, 2022; see also call for inputs into OHCHR’s upcoming report:

[21] A/HRC/23/47, 9 April 2013, para 109.

[22] For more information: https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/advisory-committee/human-rights-implications

[23] Houdmont, Virginie. “Brazil country visit – preliminary observations by Special Rapporteur Voule.” Free Assembly and Association, April 11, 2022; see also full report Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, Visit to Brazil, May 2023.

[24] UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, Information note on responsible business conduct in the arms sector, 2022.

[25] See OHCHR reports A/HRC/51/15 (2022); A/HRC/53/49 (2023); A/HRC/56/42 (2024)

[26] Robert McCorquodale (Chair), Fernanda Hopenhaym (Vice-Chair), Pichamon Yeophantong, Damilola Olawuyi, Elzbieta Karska, Working Group on business and human rights; George Katrougalos, Independent Expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order; [...] States and companies must end arms transfers to Israel immediately or risk responsibility for human rights violations: UN experts, 20 June 2024.

[27] CSP9 President, Working Paper submitted by CSP9 President: The Role of Industry in Responsible International Transfers of Conventional Arms, 21 July 2023.

[28] Austria, Ireland, Mexico, Joint Working Paper submitted by Austria, Ireland and Mexico: Responsible Business Conduct and the Arms Trade Treaty, 21 July 2023.

[29] ATT Secretariat, ‘Final report’, 25 August 2023.

[30] See for example: Chair of the ATT Working Group on Effective Treaty Implementation ‘Letter by the WGETI Chair ahead of the CSP10 preparatory process’, 22 January 2024.

[31] On a number of occasions, the Anti-Personnel Landmines Convention (APLC) community has received briefings from the OHCHR on the rights of persons with disabilities and how that intersects with the obligations under the APLC on victim assistance. But this cross-silo work remains anecdotal.

The Author

HINE-WAI LOOSE

Hine-Wai Loose is the Director of Control Arms and based in Geneva. Previously, Ms. Loose worked as Project Manager for the Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance (DCAF) on cyber security governance in the Western Balkans region. From 2011 to 2017, Ms. Loose served as the Deputy to the Implementation Support Unit for the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) in the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. In this role, she led on the issues of anti- vehicle mines, explosive weapons in populated areas and lethal autonomous weapons systems. Ms. Loose started her career with the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade where she worked across the issues of disarmament, environmental negotiations, humanitarian affairs, human rights and international law.

FLORENCE FOSTER

Florence Foster led the Quaker UN Office’s Peace & Disarmament work in Geneva until recently. She specializes in conflict transformation, networked policy development and facilitating policy conversations, with a thematic focus on arms control, corporate responsibility, social justice and human rights. She began her career at the Global Protection Cluster and the International Service for Human Rights in Geneva, before moving on to focus on West African conflict dynamics at the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Through her later roles at the Fondation Suisse de Déminage and Finn Church Aid, Florence led mediation and armed violence reduction initiatives in the Central African Republic.

This report is written in the authors’ personal capacity. The honorarium for this article was donated to charity.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org