Social Media, Technology and Peacebuilding Policy Brief No.193

Unpacking Affective Polarization in Afghanistan: Ethnic Politics, Elite Competition, and Online Divisive Content

Qasim Wafayezada

June 10, 2024

Abstract

Affective polarization has been a persistent feature of Afghanistan’s society and politics in the past decades. However, with the instantaneous collapse of the republic’s government and the return of the Taliban, the country has witnessed heightened affective polarization along ethnic and ideological lines. Stemming from deep-rooted historical grievances, aggregated conflicts, and over a century of failed struggles for statebuilding and nation-building in Afghanistan, the surge in affective polarization is intricately linked with the elite’s behaviour and social media use. Outbidding strategies by elites result in more extreme positions. Coupled with the dissemination of hate and harmful messages, and divisive online content, this attracts wider attention and social support against a background of dwindling inter-group trust, state failure, and uncertainty over the political prospects. This article attempts to conceptualize the complex causal relations of affective polarization, elite behaviour, and social media platforms in Afghanistan’s fragmented social and political landscape.

Contents

- Introduction

- Affective Polarization

- Dynamics of Polarization in Afghanistan

- How Do Elites Drive Affective Polarization?

- Social Media

- Conclusion

Introduction

Afghanistan’s politics and society have been characterized by social fragmentation and political polarization throughout its modern history, especially in the past half-century, marked by continued violence and armed conflict. Modern Afghanistan, carved out of a fragmented tribal and ethnic milieu in the 1880s, has reinforced social divisions under conditions of excessive use of coercive force and unprecedented levels of oppression, marginalization, and discrimination against minority ethnic and religious groups (Hopkins, 2008; Rubin, 2002; Barfield, 2010). Based on some sources, Afghanistan is home to over 55 ethnic groups speaking 45 languages (Allan, 2001, 545), from which four ethnic groups— Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, and Uzbeks—wield significant political weight and have played a decisive role in shaping the political trajectory of the country. The relationships between ethnic groups have been both cooperative and competitive. However, dynastic rivalry, coupled with the tribal structure of Pashtun society, has been the primary cause of political instability and discontinuity. With 17 different national flags in the 20th century (Allan, 2001, 545), Afghanistan has witnessed a series of revolutions and political transitions that have left deep scars and varying legacies in Afghan society. Today, given the aggravated historical and current grievances and frustrations over continued war and violence, migration, and displacement, Afghan society and politics remain intensely polarized, fractured, and fragmented. The Taliban’s return to power on August 15, 2021, was perhaps the final blow to the fledgling democratic political process and nation-building efforts that were put in motion by the Bonn Agreement in 2001.

Taliban rule, associated with oppression, excessive use of violence, and discriminatory and exclusive policies, has deepened social divides, which, in one way or another, enforces two major trends. First, intensification of affective polarization along ethnic, ideological, and gender lines, and second, as the public sphere shrinks, political and social activism is left with no option other than to move online. With severely constrained political action in the region, exiled political and civic activists have found themselves compelled to take refuge in the online public sphere and use ICT for networking and mobilization. Today, political parties, civil society organizations, human rights activists, and the new generation of so- called “digital natives” (Kamber, 2017; Prensky, 2001), including the Afghan diaspora around the world, are making the utmost use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), especially the social media platforms, for political expression and influencing the public opinion. Therefore, social media platforms have gained more importance than ever in Afghanistan’s political and civic activism despite considerably limited access to internet use.

Mirroring the long-standing political fragmentation, coupled with elites’ competition, online divisive content significantly increases affective polarization. Social media users and online networks are fragmented along ethnicity, language, ideology, and gender issues, which is conducive to the intensification of the emotionally charged polarization process in Afghan society. Understanding the nature, scope, and scale of affective polarization and the effect of social media and elite behaviour is crucial to any effort to build common ground that would allow the deconstruction of affective polarization and constructive interaction and dialogue conducive to peace. Therefore, this study is motivated by increasing affective polarization, associated stereotypes, deindividuation, dehumanization, and vilification of out-groups which are seen as alarming signs that call for constructive and positive intervention.

This study adopts a multi-disciplinary perspective to offer an analytical framework for the complex causal relations of increasing affective polarization with elite competition and social media in Afghanistan. Drawing from the extensive scholarship on affective polarization, the research incorporates theories from social identity, elite competition, and communication to provide a systematic explanation.

Affective Polarization

Affective polarization is a relatively new term that denotes an old phenomenon and refers to an individual’s identification with a particular identity, including ethnicity, ideology, or political party, giving rise to favouritism, mistrust, and bias (Druckman & Levendusky, 2019). In other words, affective polarization occurs when socio-political divisions stem from emotional attachment to ethnic or ideological identities rather than a rational evaluation of policy preferences or distinctions. While issue-based or opinion-based polarization is a constructive and integral part of democratic deliberation and an essential component of a vibrant and dynamic society, affective polarization evolves into a sharp in-group and out-group division, where individuals dislike and distrust members of another identity group (Iyengar et al., 2019). However, the existing literature on affective polarization, to a large extent, focuses on partisan and electoral divides linked to different understandings of policies and politics (Már, 2020; Reiljan et al., 2023; Voltmer, 2006; Garrett et al., 2019), in divided societies experiencing prolonged armed conflict and high levels of aggregated enmity, ethnic politics and ideological extremism which take precedence over partisan politics. In an ethnically divided social context, party politics is correlated with ethnic politics and functions as ethnopolitical factionalism rather than thriving distinctive rational ideological features or policy preferences.

Fortunately, an emerging and burgeoning body of scholarship on affective polarization has explored and investigated ethnic politics and ideological extremism. Iyengar et al. (2019) argued for three types of causal explanations for affective polarization: social cleavages, ideological differences, and political messaging. An important source of this scholarship comes from social identity theory that relates affective polarization to ethnic politics and identity-based group interactions (Bradley & Chauchard, 2022; Iyengar et al., 2012; Tajfel et al., 1971). From the perspective of social identity theory, ethnic identity constitutes the main foundations of social and political polarization, where contention and conflict over issues of equal access to political, cultural, and economic opportunities and development widen the divide and get intertwined with conflict escalation and ethnic mobilization that enforces in-group and out-group divisions (Mason, 2016; Stewart et al., 2020; 2021). This argument is supported by historical records of civil wars, with over 70 ethnic conflicts in the past 50 years (Quinn & Gurr, 2003; Williams, 1994).

Anthropologists and scholars using social identity theory provided earlier explanations for social polarization in terms of the formation of specific in-group communication systems and proposed ethnicity as the most salient type of identity and the main driving force of conflicts in divided and war-shattered or conflict-prone settings (Barth, 1998; Smith, 1994; Chai, 1996). Naroll (1964, 284) defined ethnicity as biologically self-perpetuating, with shared fundamental cultural values, a system of membership and identification, and a field of communication and interaction. An ethnic group explains “their own and other groups’ successes and failures in terms of racially imputed intellectual capabilities and ethnically marked cultural propensities” (Snajdr, 2007, 604). Social psychology and symbolic interactionism scholars contributed to this debate by outlining a two-dimensional commitment defining the salience of ethnic identity that includes interactional commitment (Serpe 1987, 45) and affective commitment (Stryker, 2003, 85).

Therefore, it can be said that affective polarization has its roots in the initial affective commitment. As empirical studies show, it is positively associated with psychological biases (Kvam et al., 2022) and intensifies with ideological extremity (Hopp et al., 2020) such as ethnonationalism and radical Islamism. In developed countries with well-established democratic institutions and lower levels of persona-centrism, ideology plays a cross-cutting role and redirects social polarization from ethnic identity to one revolving around political ideology and policy to varying degrees (Bright, 2018; Iyengar et al., 2012; Rogowski & Sutherland, 2016). In contrast, in divided, developing, and undeveloped countries such as Afghanistan, instead of superseding the ethnic division, ideology only complicates the convoluted politics of identity cleavages and provides additional motivation for conflict and a parallel dividing line for affective polarization. Weak and dysfunctional institutions, exclusive structures and policies, and the absence of institutional channels for accommodating ideological differences cause increasing tensions and conflictual relations, resulting in ideological extremity precipitating a latent or active armed conflict.

In other words, ideology becomes a secondary means of social and political sorting and identification with a dual and shifting role in changing the nature of polarization. Under such socio-political settings in divided societies, even extreme ideological proclivity cannot overcome the salient ethnic identification propensity. This was evident in Afghanistan, as the two generations of Islamists, the mujahideen and the Taliban, failed to overcome ethnopolitical factionalism with jihadism or Militant Islamism. The first metamorphosed into ethnopolitical factions fighting a devastating civil war in the 1990s, while the latter has been overwhelmed by its Pashtun identity in its national political manifestation (Wafayezada, 2023).

The impact of elite behaviour and social media

In divided socio-political settings, elite behaviour and social media can significantly impact the scope and scale of affective polarization. To invoke the scholarship from elite competition and instrumentalist theories, elites tend to instrumentalize identity and reinforce polarization in politics (Brass, 1991; Olzak, 1983). Elite polarization is a precursor to social polarization and shapes political behaviour (Zingher, 2022). Political leaders are inclined to reflect upon and represent ethnic aspirations and mobilize support on an ethnolinguistic basis. Under such circumstances, the more inequality and injustices which exist, the more leverage is found for elites and parties to advance their agendas on an identity basis. In most cases, elites fixate their actions on in-group affections and emotions, which leads to populism, or what some scholars have termed as ‘populist polarization,’ referring to how populist leaders articulate the existing ethnic, ideological, or partisan divisions (Stefanelli, 2023, 1).

Therefore, the pre-existing aggregated adversaries of identity groups and conflict escalation, together with the elites’ machinations or manipulation, shape the social media content and create a spiral of divisive content and behaviour. Nordbrandt (2021, 1), in his study, found that “it was the level of affective polarization that affected subsequent use of social media.” Social media use per se can contribute to increasing moderation or tolerance through exposure of the users to various contending ideas and their rational or emotional underpinnings. Asimovic et al. (2021,1), through an experiment in Bosnia and Herzegovina, also found that during one week of heightened identity salience, the anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre, “people who deactivated their accounts, reported lower out-group regard than the group [which] remained active.” However, contextual conditions matter; it can be argued that social media’s content and its effect need to be understood and analyzed as part of a sociopolitical ecosystem that is influenced by social tensions and conflicts and it exerts an impact in return by amplifying those conditions. Given the emotional intensity of ethnic and ideological divides under conditions of conflict escalation, social media contributes to increasing affective polarization.

To put it in the words of Hecht and Ribeau (1984), “ethnic identities are expressed and transmitted through communication,” and social media platforms, as argued by Levo- Henriksson (2007, 2), have the “ability to diffuse group identities” by creating a “placeless culture” that permits invading belief systems and conceptual-political territories of others without entering them. In addition, social media, in providing a platform for individuals to express their political and ideological views without or with less restrictions and connect with like-minded individuals, amplifies affective polarization by reinforcing echo chambers (Cookson et al., 2023; Lackey, 2021; Tornberg, 2019) and spreads disinformation and misinformation (Jenke, 2023; Kubin & von Sikorski, 2021). Therefore, social media offers a vehicle for elite competition and manipulation through targeted messaging and emotional manipulation techniques under acute tensions and aggregated conflict conditions.

Social media, through uncontrolled divisive content, contributes in one way or another to heightened polarization. Acerbi (2019, 97) argues that with the hyper-availability and personalization features in social media, individuals tend to interact with like-minded people, and thus, “the pre-existent opinions are shouted back at us—the ‘echo’ in echo chambers.” The formation of echo chambers is perceived to be conducive to the radicalization of opinions (Cheng et al., 2023) and the black-and-white division of ideas that can cause increasing hatred toward out-groups. Miller et al. (2016, 181-2) noted that “social media is contributing to the rise of narcissistic, self-centered individuals,” who prefer to limit their interactions and online ties to those who share not only the same opinion but also the same behaviour, known as homophily. Mcpherson et al. (2001, 415) found that: “Homophily in race and ethnicity creates the strongest divides in our personal environments, with age, religion, education, occupation, and gender following in roughly that order.” Moreover, as Pariser (2011, 10) described, filter bubbles caused by algorithms used by social media to personalize user experience “create a unique universe for each of us” and result in intellectual isolation. In other words, social media individualizes the dissemination of information that ironically works through deindividuation and self- righteous perceptions.

In a state of intellectual isolation, individuals lose their sense of reality and tend to accept misinformation and disinformation as long as they find it consistent with their views. Under high levels of affective polarization, individuals are more likely to ‘believe in-party- congruent misinformation” (Jenke, 2023) and to feel hostility and express bias against others (Renström et al., 2023). In sum, divisive content on social media is motivated by social dynamics of conflict and division and structural sociopolitical ecosystems, but it also has attributable links to deliberate tactics of political elites, resulting in intensifying affective polarization. As discussed above, social divisions and the existence of acute and aggravated grievances provide ample space for the production and circulation of divisive content and elite manipulation.

Dynamics of Polarization in Afghanistan

The dynamics of polarization in Afghanistan involve a complex set of factors that have worked together to shape the dynamics of continuity and change in the country’s modern history, marked by the politicization of ethnicity and activation of ethnic boundaries, ideological extremity, and problematic gender boundaries. Formation of the state in the 1880s with sheer brutal force came at a high cost for Afghanistan, cultivating endemic inter- ethnic enmity and leaving deep scars in the collective memory of identity groups, especially the Hazaras, who suffered a massacre tantamount to genocide, were sold into slavery and became subject to forced displacements during this process. These ethnic and identity- based grievances have been coupled with continued structural violence and oppressive policies of the governments, causing an aggregation of grievance and struggle for change.

However, the emergence of ideology in the modern sense of the term as a significant political factor dates back to the establishment of leftist and Islamist parties during the "Decade of Democracy" (1964-1973) and the ratification of a new Constitution. During Daud’s Republic government, the socialist parties gained momentum, enabling them to infiltrate the administrative and military establishments and ultimately overthrow Daoud’s government by a bloody coup d'état on April 28, 1978. At the height of the Cold War, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan triggered an unparalleled surge in ideological extremism, marked by the introduction and promotion of the two revolutionary forces of militant Islamism or jihadism and revolutionary socialism, overwhelming the much weaker urban- centric liberal elites. These elements collectively heightened the complexity of the convoluted politics characterized by fragmentation and polarization (Rubin, 2002; Olesen, 1995).

The withdrawal of the Soviets, followed by the fall of Dr. Najibullah’s government in 1992, brought an end to over a decade of leftist rule in the country, and the page was turned in favour of the Islamists who came to dominate Afghanistan’s politics and society buttressed with the politicization of ethnic identity. The absence of an international initiative for an inclusive and broad-based government in the post-Soviet period created a political vacuum that, in one way or another, catalyzed ethnic competition with new ideological motivations, struggling to reshape and redefine the political structure. The failure of jihadi ethnopolitical factions to agree on an inclusive government and political order resulted in a destructive civil war from 1992 to 1995 (Rubin, 2002), which deepened the social divides and aggravated grievances, contributing to unprecedented ethnic mobilization and activation of even dormant ethnic identities. The rise of the Taliban in 1994, who promoted Islamic extremism, and their subsequent takeover of power in 1995, furthered affective polarization and collective frustration over the political prospect of the country and the coexistence of its various ethnolinguistic groups (Nojumi, 2002).

In the post-2001 period, Afghan politics was shaped by liberal ideas and pro-democratic aspirations with extensive support from the international community and a US-led military coalition that terminated the Taliban rule and put in motion a new democratic political process. However, ethnic identity retained a crucial role in shaping the political landscape and proved more salient than any other sociopolitical factor; militant Islamism of the Taliban continued to challenge the pro-liberal democratic forces with armed insurgency and violent conflict for nearly two decades. Taliban insurgency exerted a significant impact on the dynamics of power and politics in the government as well, which was already mired in ethnic competition, elites' predatory behaviour and outbidding policies, endemic corruption, and diminishing legitimacy, with contested presidential elections of 2014 and 2019. As a result, Afghanistan's political elites failed to take advantage of a golden opportunity, presented to the country in the post-2001 period, to navigate the country through the existing and unfolding challenges. Instead, Afghan society and politics remained intensely polarized along ethnic and ideological lines.

Under such an ethnically divided and emotionally polarized environment, even the republic government’s collapse was perceived to be part of a ‘secret deal’ and an ethnic conspiracy by Pashtun elites on both sides of the government and the Taliban for the restoration of Pashtun domination in Afghanistan. Some information that became public after the Republic’s fall, such as the final telephone conversation between Hamdullah Moheb, President Ghani’s national security advisor, and Khalil al-Rahman Haqqani, a key figure in the Haqqani network, confirmed such a perception. In that short conversation, Moheb, on behalf of President Ghani, had allegedly signaled for the Taliban’s entry to Kabul; this went against the previous agreement reached with and assured by the US envoy, Zalmay Khalilzad, that the Taliban would not be entering Kabul until an interim administration or transitional mechanism was sorted out (Abbas, 2023, 3-7). However, Moheb later told CBS News that, in that call, the Taliban asked for surrender and to negotiate later (CBS News, 2021). Nevertheless, for non-Pashtun minority groups, who were pushed out of the game and rendered dysfunctional and excluded, the fall of the republic had a significant impact, whether they saw it as an ethnic conspiracy or otherwise.

The Taliban, upon their ascendance to power, nullified the 2004 Constitution and all its associated laws and regulations while promoting Sharia law. The Taliban de facto government declared a ban on political parties, women's work, girls' education higher than sixth grade, and the application of gender apartheid. Such policies have resulted in the elimination of all civic and political activities and, especially, a complete erasure of women from society. The severity of women’s exclusion from all social and political activities and denial of their basic rights and liberties also added the gender issue as the third dimension to polarization in Afghanistan’s society and politics, notwithstanding ethnic and ideological polarities. Under the current gender apartheid policy of the Taliban, gender and, more specifically, women's rights is not merely a simple matter of difference in policy or opinion but an existential issue for Afghan women and, thus, a definitive factor in shaping the future prospects for peace and dialogue. An unprecedented crackdown on freedom of expression and association to eliminate any opposition or criticism has contributed to furthering social divides, eroding social capital, and dismantling political platforms for constructive dialogue and discussion that would help to bridge the gaps (Wafayezada, 2023).

Increasing affective polarization under the Taliban’s rule

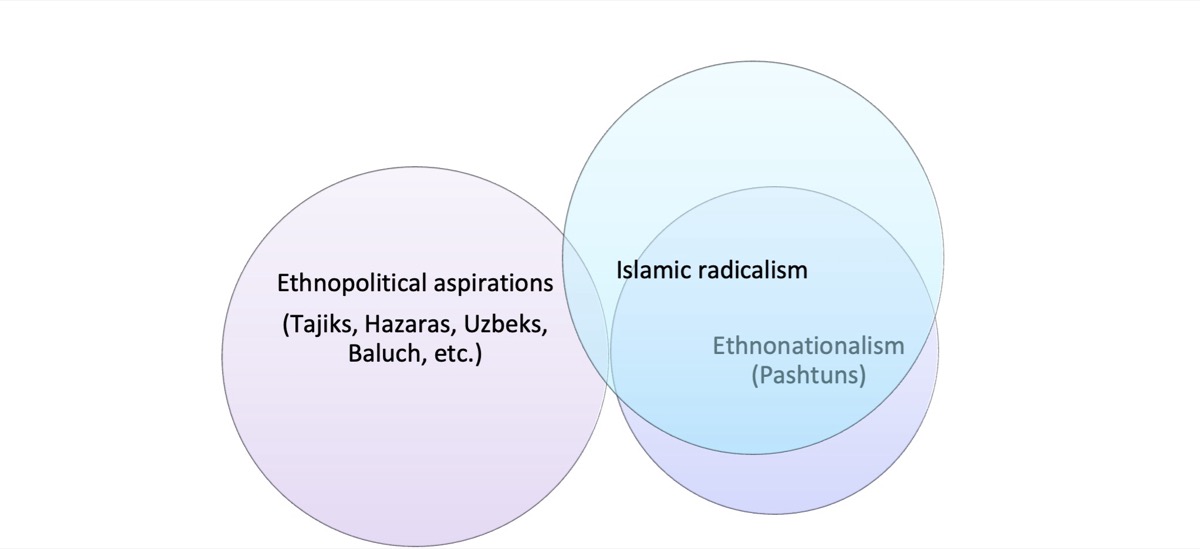

Against this historical backdrop, the Taliban has incorporated a mixture of Islamic radicalism and Pashtun ethnonationalism motivated by primordial feelings, that I have termed ‘hybrid extremism’ (Wafayezada, 2023). This ideology predominantly aligns with Pashtun ambitions for control over Afghan politics, while starkly contrasting with the aspirations of non-Pashtuns. Ideologically, the Taliban's radicalism creates a rift with pro- liberal factions within the Pashtun community, while finding common ground with Islamist elements among other ethnic groups, albeit to a lesser extent.

In the complex socio-political landscape of Afghanistan, marked by the politicization of ethnicity, longstanding historical grievances, and heightened tensions in interethnic relations, the fusion of radical Islamism and Pashtun ethnonationalism shapes a political environment characterized by exclusion, discrimination, and subjugation of minority groups. The Taliban’s return to power, coupled with the reinstatement of oppressive authoritarianism, triggers a deepening polarization in a fractured social context. In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s ideological extremism (Islamism) reinforces Pashtun ethnonationalism, serving as both justification and motivation. For instance, the Taliban's implementation of gender apartheid and their ban on girls' schooling and women's employment align with the strict adherence to the Parda code of Pashtunwali (Barth, 1998), which dictates the separation of males and females, finding support among the larger rural and nomadic Pashtun population. In addition, the Taliban, in their Islamism, manipulate the hidden code of power in Pashtunwali (Hawkins, 2009, 21) and foster a unifying allegiance across tribes that would otherwise vie for power, as exemplified by the historical competition between the Ghilzai and Durrani tribes in the modern history of Afghanistan since 1747.

As noted by Lieven (2021,10), “strong espousal of Pashtun ethnic nationalism by the state inevitably frightens and infuriates the other large ethnic minorities of Afghanistan,” especially when it is defined by Islamic radicalism and militant extremism, making it more brutal and coerciveimg02. The Taliban’s insertion of Pashtun ethnonationalism into the official policy of the government and identity of the state, highlights ethnic identity in the most politicized sense. Efforts such as promoting Pashtu as the national language at the expense of the Dari language, which has been eliminated from official use, banning activities of political parties and all social and political platforms, forcing evictions of non-Pashtuns and resettlement of Pashtuns in traditional enclaves of other ethnic groups for the purpose of social control, project fear and put other ethnic groups in a defiant position. As a result, ethnic identity, along with all its associated features, such as language and culture, has been politicized even further, turning it into the main driving force of conflict and polarization.

This situation, first and foremost, poses an existential and crucial question over the prospects of peaceful coexistence under an authoritarian system that functions through the politics of exclusion and suppression.

Figure 1: The exclusive nature of Taliban's hybrid ideological extremity.

Figure 1: The exclusive nature of Taliban's hybrid ideological extremity.

The blended ideology of ethno-nationalism and Islamic radicalism of the Taliban serves primarily for ethnic mobilization to secure social support from amongst the Pashtuns' various tribes by giving them a sense of unity through sustaining in-group affinity and out- group animosity. On the side of excluded ethnic groups, such as Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, etc., ethnic collective consciousness is enforced by their exclusion and subjugation. However, sub-divisions into Shiite and Sunni may add to the complex spiral of affective polarization while some cross-cutting cultural features, such as Dari language, might unite broader societal segments. Yet ethnic identity remains the chief cause for driving affective polarization and emotional rifts. Islamic radicalism, while being the raison d'être of the Taliban, contributes to the consolidation of the Taliban’s ethnic politics through the rejection of a constitutional order and all man-made laws and regulations, the notion of the people’s sovereignty while promoting the perpetuation of jihad.

Shaikh Abdul Hakim Haqqani (2022, 18), Taliban’s Chief Justice, in his book titled “Al Emarat al Islamiah wa Nizamuha,” which translates as “The Islamic Emirate and Its Organization,” with a foreword by Taliban’s leader, Mawlawi Hebbatullah Akhundzada, reflects their attempt for the perpetuation of Jihad:

Mujahidin of the Islamic Emirate is not permitted to give up or cease jihad upon the withdrawal of the US forces and its allies, as it was not the only goal of Afghans’ jihad. But their goal was to restore the rule of Allah’s law on Afghans and to live under the flag of Sharia.

The Taliban are also making the utmost use of Pashtun ethnic identity in establishing both solid foundations for social support and redefining Afghanistan's identity as a Pashtun and Islamic Emirate on the world map. The Taliban efforts in constituency mobilization along Pashtuns’ ethnic and tribal lines adversely affect national politics, but could be directed toward peace and stability. Given the social and political fragmentation and failed attempts at nation-building around the Pashtuns’ identity as an ethnocultural core, the Taliban find it highly challenging to create a sustainable status quo without addressing the causes of fragmentation and polarization. The oppressive authoritarianism of the Taliban, while enforcing ethnic competition, lays the ground for intense elite competition and the adoption of proportionately extreme methods by the political elites of excluded and marginalized ethnic groups. In other words, the Taliban’s extremism only breeds extremism. On the one hand, their survival hinges upon continued and increased oppression and ideological extremity, and on the other, it generates counterforces charged with extreme ethnonationalist ideology and intense affective attachment to ethnic identity.

How Do Elites Drive Affective Polarization?

The extreme ideological stance of the Taliban, steeped in ethnonationalism and Islamism, has led to the marginalization of moderate perspectives and voices. The Taliban’s mobilization strategies among the Pashtuns have been based on a highly charged ideological motivation, sensationalism, and play on the emotions and aspirations of local Pashtun communities. In addition, the Taliban uses extensive coercion and intimidation to either silence or sideline urban intelligentsia and moderate voices among Pashtuns. Meanwhile, ethnic minorities facing oppressive policies, discrimination, and harsh repression from the Taliban see moderate and conservative factions as lacking strength and determination to bring about a positive change or subdue the Taliban’s exclusionary and discriminatory policies and oppressive rule. Therefore, with increasing affective polarization due to the severity of oppression and exclusion, the disparate expectations of excluded and oppressed identity groups trigger intense elite competition for ethnic mobilization.

In their seminal work, Rabushka and Shepsle (1972, 139) argued that in plural societies where ethnicity is salient, politics of moderation give way to politics of outbidding, in which “communal groups favor extremist positions over a moderate or ambiguous one.” However, some scholars argue that ethnic competition is not sufficient to prompt ethnopolitical parties to resort to an outbidding strategy. Their political ideology is also important in affecting strategies available to parties (Stewart & McGauvran 2020, 405). A notable deficiency in the existing scholarship is that outbidding is applied and examined as an electoral strategy for political parties (Chandra, 2005; Zuber & Szöcsik, 2015), while outbidding towards extremist positions may take place under conditions of ethnic competition in non-democratic settings with heightened ethnic polarization, as in the case of Afghanistan.

The outbidding strategy was extensively applied during the ethnic mobilization and civil wars of the 1990s, mostly in intra-ethnic elite competition to win over others. It continued to be applied to varying degrees in the following decades. However, due to social and political transformation and the changing political context in the post-2001 period, the decline of the old guard ethnopolitical leaders, and the rise of a new generation of political elites, the application of outbidding strategy also transformed in method and severity.

During the past decades, a consensus on nationhood and addressing ethnolinguistic diversity through a more inclusive and representative political structure existed among both the old guard and the new generation of Afghanistan’s political elites. However, it was challenged occasionally by the rising number of mavericks and Ronin politicians who tended to define themselves independent of existing political parties. The collapse of the government and the suppressive behaviour of the Taliban have broken that consensus, precipitating the application of extreme outbidding strategies along ethnic and ideological lines. Notwithstanding the urban-rural split of elites in Afghanistan, it is important to make a distinction between the old-guard and new elites’ behaviour.

The old-guard elites

The old-guard elites played an active role in defining ethnic boundaries and building their political bases upon ethnic representation in power, which resulted in heightened affective polarization. The old guard included ethnopolitical and factional leaders of Mujahideen, who gained prominence with the Soviet invasion and established themselves as the political leadership of identity and ideological groups over the past four decades. The jihadi ethno- political factions, along with Afghan political circles in Rome and Cyprus, were the main signatories to the Bonn Agreement in 2001 and came to play a pivotal role in shaping the post-2001 political trajectory. Despite internal factionalism and splits, the jihadi ethno- political factions maintained their social influence and political weight and represented certain ethnic groups in peace and conflict situations. The old guard leaders, going through stages of cooperation and confrontation, had transformed from ruthless warlords to flexible politicians.

With their theocratic dogma melting, they started to view politics as a business rather than a battleground for conflicting extreme ideologies. Such transformation, however, had contributed to their moral corruption. In a political sense, this helped them soften their ideological stance and become more flexible in joining inter-ethnic alliances and national- level alignments. Arguably, a similar change of behaviour and perception was taking place, to some extent, among the Taliban’s leadership. The first generation of the Taliban—or in terms of Hassan Abbas (2023, 243-6), ‘the old Taliban’ who had massacred thousands of innocent civilians, especially the Hazaras—were learning from their previous short-lived rule and were demonstrating incremental shifts, drifting away from their initial ultra- extremist views. Nevertheless, armed insurgency and promoting extremism and violence as their modus operandi had hampered tangible transformation in their outlook and behaviour. Even if some had changed positively, they were either weakened and sidelined or old and dead.

The transformation in the old guard elite behaviour contributed to rebuilding social cohesion and trust in the post-2001 period to some extent, as they shifted their policies of ethnic mobilization for political gain toward rent-seeking strategies in larger inter-group networks, for which Sharan provides a detailed account (Sharan, 2023). One of the main explanations for their behaviour change was the satisfactory incentives provided in the post-2001 de facto consociational political structure, with each political faction having a quota in government positions under a ‘grand coalition,’ as termed by Lijphart (1969). As part of their survival policy, they played the ethnicity card whenever their interests were threatened by the government, which would change once their interests were secured, a hypocritical pretense that gradually undermined their political strength and social support bases. In addition, the rapid social transformation and mobilization of new young forces into politics and society, coupled with the inability of the government to incorporate them or accommodate their aspirations, had outpaced the survival efforts of the old-guard leaders.

With the decline of the old guard’s monopoly of ethnic representation in the power structure and the erosion of their social authority, the new elites and the young generation came to challenge them more explicitly in a theatrical manner as early as 2014. But the ‘Tabassum Movement’ after the Taliban’s execution of Shukria Tabassum and six other Hazaras in November 2015, followed by Junbesh-e-Roshnayi-e (the Enlightenment Movement) in 2016 and Junbesh-e Rashtakhiz-e Taghir (The Uprising for Change Movement) in 2017, had a cataclysmic impact on the authority of the old guard. As noted by Bose et al. (2019), all three major movements criticized the government for making decisions on ethnic bases, causing exclusion and marginalization of Hazaras, Tajiks, and Uzbeks. Finally, the collapse of the Republic Government left the 'old guard' political leaders with diminished influence. Lacking military capability and the means for armed resistance in the post-2021 political landscape, they faced harsh criticism for their failure to provide effective leadership.

Today, most of the old-guard ethnopolitical leaders are allied under the Supreme Council for National Resistance, in what is called the Ankara Council. The alliance includes, among others, Abdulrab Rasul Sayyaf, Marshal Dostum, Mohaqqeq, Ata Mohammad Nor, Salahuddin Rabbani, Yonus Qanoni, and Ahmad Zia Massoud. Those actively seeking armed resistance have gathered around Ahmad Massoud’s National Resistance Front, with Tajikistan as their main operational base. Dr. Abdullah and former President Hamed Karzai are in Kabul, their actions strictly observed by the Taliban to such a degree that some have called them as hostages. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a key figure among the old-guard politicians who represented an ultra-Islamist and Pashtunist political outlook until the rise of the Taliban in 1994, has lost his social support to the Taliban while being outbid in extreme political manifestation of the Taliban. He also resides in Kabul, with restricted political activities.

Nevertheless, the Taliban see these old-guard leaders as their main counterparts in peace and conflict. A member of the Afghan government negotiation team once told the author that the Taliban were avoiding negotiating with the republic government in Doha and had emphasized that their main counterparts that they should negotiate with were ethnopolitical leaders. Recently, Taliban leaders such as Serajuddin Haqqani have repeated their call to the ethnopolitical leaders to return to the country and join the Taliban, which explains how the Taliban views Afghan politics through the 1990s lens and weighs up the political elites. This also indicates that the Taliban leaders think that incorporating or surrendering the ethnopolitical leaders would help them to overcome the existing challenges, especially addressing the questions of legitimacy and recognition, while the social aspirations for a free and just society and the complexity of social dynamism remain out of sight for the majority of Taliban leaders.

Maverick leaders, ronin politicians, and new elites

In post-2001 Afghanistan, youth mobilization, including unprecedented women's activism, showcased social transformation. As argued by Huntington, in a changing context, the rapid mobilization of new forces, coupled with the slow development of institutions (Huntington, 1968, 4) was driving the country to the precipice of instability and violence. Afghanistan’s demographic structure is composed of an overwhelmingly young population, indicating a ‘youth bulge.’ In 2014, 20 percent of Afghans were between 15 and 24 years old, and 48.4 percent were under the age of fifteen (Central Statistics Organization, 2014, 10). The twelve million juveniles and youth constituted the core dynamism of change and the main forces for both violence and development. Studies show that the youth bulge in general (Flückiger & Ludwig, 2018) and urban youth, in particular (Korotayev et al., 2023), have positive correlations with violence and terrorism in multiple and divided societies suffering from the slow pace of economic development and low levels of political stability.

Mobilization of the new generation, who sought a voice and agency in the larger political and social structures controlled by ethnopolitical leaders and their small circle of loyalists, had turned the youth into a ‘generation of protest.’ With the failure of the government to incorporate or accommodate the young forces among the Pashtuns and effectively address the socio-economic challenges, as argued by Gaan (2015), ‘slipping into the hands of the Taliban, which provide[d] better economic prospects, [could] become a fait accompli.’ Among the non-Pashtuns, Afghanistan witnessed the rise of a new generation of elites and a young social and political force who came to challenge the old-guard leaders on the same ground of ethnic politics but with a more assertive tone.

The three movements of Tabassum (2015), Roshanayi-e (2016), and Rastakhiz (2017), while predominantly Hazara or Tajik, included clusters of youth activists from other ethnic groups as well. In addition, such movements inspired the new generation of elites among other ethnic groups to take on the same assertive socio-political stance. Huntington (1968, 4), drawing on de Tocqueville's observation, noted that an important factor behind the instability and violence in developing countries was “the rapid social change and the rapid mobilization of new groups into politics coupled with the slow development of political institutions.” Afghanistan was facing a similar situation, with the rapid mobilization of a new generation of youth forces and elites, who were met with limited employment opportunities, economic inequality, and political capability to give direction and purpose or accommodate and incorporate these new forces.

Defying the overwhelming persona-centrism in political parties and the state apparatus pushed the newly mobilized forces of young and educated Afghans to take on different paths. While movements mentioned above vividly came to echo ethnic aspirations for equality and inclusion, in competition with the entrenched old-guard elites who had turned into kleptocrats, there were other movements that voiced major and wider concerns. The movement against unemployment was perhaps the most exemplary among those that transcended ethnic boundaries. In 2015, the movement went on strike for 55 days in front of the Parliament building and carried slogans such as “Not Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara, or Uzbek, but we are all unemployed” (Bahari, 2015).

An important characteristic of the new elites and young social and political activists was that they constituted the main forces in the mainstream media and civil society and were the digital natives in terms of social media use. Civil society, with over 5254 local NGOs (MOE, 2021) and 4476 registered associations (MOJ, 2021a), was perhaps the most important platform for youth activism, where they could play an important role in monitoring the government's accountability and effectiveness and translating the citizens' demands into civic action. In the political arena, although they lacked an established social base, given the socio-political transformation that was in progress, the new elites were advancing to play an important role in the redefinition of the country’s future political trajectory. The new elites had embarked on entering politics through the parliament, government offices, and business networks, and some had established their own political parties. More than half of the 72 political parties registered with the Ministry of Justice by 2021 were established by young political activists (MOJ, 2021b). New maverick leaders had emerged as a daring and potent political force, challenging the old-guard political leaders.

With the collapse of the Republic and the return of the Taliban, youth activism was impacted negatively by the instantaneous and catastrophic political change that dashed their hopes and aspirations for a better future. The immediate response from the young generation was to frame their thoughts and reactions by identity and ideology. They came to blame the old- guard politicians for their ineptitude and their lack of determination and leadership qualities to navigate the country through the complex challenges it had faced. On the other hand, as the Taliban manifestations became vividly centered around Pashtun identity, projecting fear and a sense of exclusion and marginalization, identity politics was reinvented among young elites, along with fierce opposition to the Islamic radicalism of the Taliban.

Social Media

Social media use has had an enormous impact on elite behaviour and continues to drive affective polarization in Afghanistan. Traditional elites leveraged legacy media to engage with their party members and distribute political information. Conversely, new political elites found social media more efficient and convenient, requiring minimal or no financial investment while offering greater accessibility and personalized features. To retain influence within the socio-political landscape, ethnopolitical leaders established their own media platforms, such as newspapers, television, and radio stations. For instance, Burhanuddin Rabbani, the former president and leader of Jamiat Islami, founded Noor TV; Marshal Dostum, leader of the Junbesh-e Melli party, owned Ayena TV. Additionally, Karim Khalili and Mohammad Mohaqqeq, both Hazara leaders, created Negah and Rah-e Farda TV stations, respectively, while Rasul Sayyaf established Dawat TV, among others (Procter, 2015). These outlets promoted ethnic and political agendas but were also bound by mass media laws preventing the incitement of ethnic or religious animosity and the dissemination of false information to a large degree.

After the introduction of social media in 2007, it took several years to become a commonly used medium of social and political expression in Afghanistan. Over a decade of investment in cell phone and internet connectivity has changed the information and communication system. According to the World Bank (2020) and ITU (2022a, 2022b), in 2020, there were 27.04 million mobile connections, 68.7 percent of the total population, of which 9 million had regular internet access in all 34 provinces, constituting 22.9 percent of the population. Afghanistan had 4.4 million social media users in July 2022, constituting 11.2 percent of the total population. Data published in Meta, LinkedIn, and Twitter advertising resources indicates that Facebook had 4.4 million users in Afghanistan in early 2022, making it the leading social media platform, followed by Instagram 552,000 users, LinkedIn 450,00 users, and Twitter (X) 319,000 users (Kemp, 2023; Statcounter, 2022). In addition, a similar number of social media users among the Afghan diaspora communities worldwide also play a significant role and are highly engaged in peace, human rights, ethnic politics, and other political and social debates. However, a Gallup survey (Nusratty & Crabtree, 2023) reveals that the digital divide remains in Afghanistan, with 25% of men reported having access to the internet versus 6% of women, which signifies the gender gap and the importance of bringing this to the fore in Afghanistan's social and political discourse.

In recent years, social media platforms have significantly evolved into pivotal arenas for expressing identity, debating ideological stances, and catalyzing political movements. Dating back to 2015 with the Tabassum Movement, Facebook and Twitter emerged as focal conduits for communication and mobilization. This trend gained momentum and sophistication during subsequent movements such as Roshanayi-e (2016) and Rastakhiz (2017). Although social media was not exclusive to the new elite, they extensively harnessed it to express opinions openly, largely unchecked by censorship or robust content oversight. This unbridled usage led to widespread dissemination of disinformation, misleading content, hate speech, and divisive narratives.

To combat the overwhelming presence of new political elites, open flow of information, and direct attacks on their personal lives, government officials, ethnopolitical leaders, and emerging political figures resorted to social media trolling tactics. This strategy allowed them to avoid direct association or culpability for disseminating hate speech or inciting the masses. They deployed hundreds of trolls on Facebook and Twitter, humorously labeled by the public as 'Facebookchalawoonki.'

The use of social media contributed to increasing affective polarization, inter alia, in two ways: first, by mirroring the social divisions vividly and amplifying discriminatory practices in the government offices, giving ethnic and ideological interpretation to offline events, aided by stereotypes, dehumanization, and deindividuation and generalization of individual actions. Especially under increased social frustration emanating from the insecurity, daily incidents of suicide attacks and car bombings targeting civilians, and growing economic inequality and unemployment, people had become more receptive to sensational and emotionally-driven content rather than moderate and more thoughtful expressions.

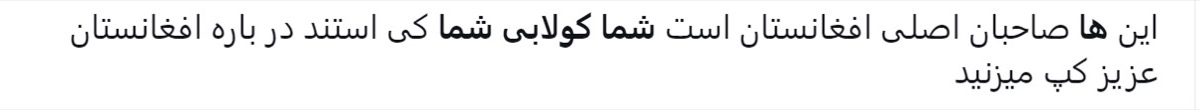

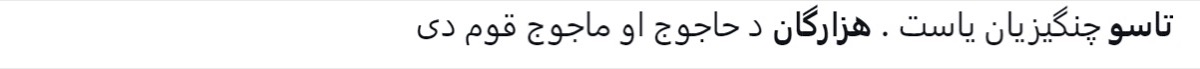

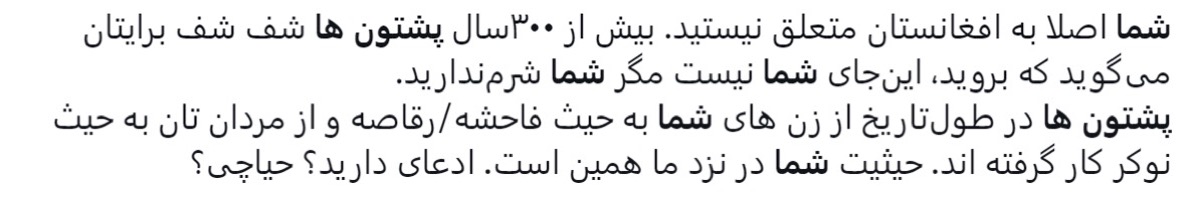

The second aspect of social media use that drove affective polarization was the possibility of echo-chambering with like-minded people and homophily with those who shared similar values, identities, and ideologies. Echo-chambering results in a sub-division of the online public sphere into several communities, with most of the debates taking place within the group. This pattern has been more visible in the post-2021 period, after the collapse of the government and the return of the Taliban to power. The Taliban’s manifest animosity towards other ethnic groups and their discriminatory and oppressive policies in terms of identity and gender is an important reason in explaining the heightened affective polarization among social media users. For example, as observed by the author, one issue that has appeared in hate messages and divisive content is the depiction of ethnic groups as a whole, either as the owner of the country or migrants, or an increase in stereotyping and belittling expressions. The following comments are some of the samples:

“They (Pashtuns) are the owners of the country, and who are you Kolabies (Tajiks) to speak about Afghanistan?”

“You are the descendant of Genghis Khan. Hazaras are the tribes of Gog and Magog.”

“You are not even related to Afghanistan. For more than 300 years, Pashtuns have implicitly told you to leave the country. This is not your homeland. However, you do not have the modesty to realize. Throughout history, the Pashtuns have used your women as dancers/townswomen and your men as slaves. This is your value with us. Do you have anything to say? Any shame?”

“Awghans (Pashtuns) are immigrants from India. They force their barbaric language of Pashtun on our people in Khurasan land.”

“You prostitutes shall never be safe anywhere!”

Lack of effective content moderation

These and much more intense hate messages got through the ineffective content moderation mechanism of social media platforms. However, Facebook and Twitter (X) have introduced and enforced complex systems of content moderation. Comparably, they are less efficient in moderating divisive content or hate messages in low-resourced languages such as Dari and Pashtu, not to mention the case-specific requirement of conflict-prone and divided societies such as Afghanistan. Social media companies such as Facebook and Twitter (X) set government regulations as the baseline for standard content moderation (Bickert, 2020, 3). For Afghanistan, the first challenge for regulatory intervention for content moderation is the absence of a legitimate government with a minimum belief in guiding principles of social media platforms, especially human rights. If content moderation is structured based on government regulations, e.g., the Taliban sharia laws, it threatens freedom of expression, something that the Taliban would want.

In addition, as argued by de Keulenaar et al. (2023, 273), content moderation policies ‘on the basis of evolving and ever-contingent public conceptions of objectionability’ are also challenging in a socially divided context with heightened affective polarization. Affective polarization entails norms and value polarization; hence, content supported by a group might be fiercely rejected and perceived as objectionable by others. For instance, one mechanism for tackling hate messages on both Facebook and Twitter is reporting by the users, which results in taking down the reported account. Such reporting can be reciprocated in an outbidding manner, which does not solve the content problem but may increase inter-group conflict.

In practice, social media platforms use a hybrid approach for content moderation, employing automated means to identify content and an additional human review if needed. Since the actions of social media platforms are guided mostly by business priorities (Díaz & Hecht 2021,3), it seems less plausible that there will be much investment in developing robust automated mechanisms and content moderation algorithms for low-resourced languages and states with a couple of million users. Therefore, compared to languages such as English, in Dari and Pashu, hate messages and harmful content circulate freely on social media without being moderated. Today, users have learned how to get around content moderation mechanisms by changing the spelling of the words carrying harmful or hate messages or typing in a dashed and broken way. In addition, social media users improvise or use very local and old hate phrases that are not included or recorded in the existing lexicons, AI detection systems, and machine learning algorithms.

Conclusion

In Afghanistan, unresolved historical grievances and ethnicization of politics coupled with state failure and the Taliban’s extremist ideological and ethnopolitical stance exacerbate the situation and cause heightened affective polarization along ethnic, ideological, and gender lines. Continued violence and conflict, mass frustration with poverty, and multiple humanitarian crises are conducive to an inter-group blame game that turns smoothly into an identity-based narrative.

As a survival strategy, political elites have built their political ideology around ethnic identity and excessively exploited social divisions and old and new grievances to create a favourable status quo or push for change. However, they used legacy media, including newspapers, radio, and TV stations, to promote their political agendas and ethnic mobilization. The introduction and development of social media platforms provided both the masses and the elites with an unchecked platform of expression. The deep-rooted and unresolved aggregated grievances, massive identity-based sufferings, discriminatory policies and actions, gender apartheid, and oppressive rule in a very coercive manner resonate with and are reflected upon in social media content.

Elites, in their competition for soliciting support from their ethnic basis, have sought an outbidding strategy that leads to the intensification of animosities and the widening of social divisions. The current high volume of divisive content on social media, ranging from stereotypes to hate and harm messages, dehumanization and deindividuation, and vilification of others, indicates a latent conflict in Afghanistan that can ignite whenever the opportunity arises and conditions are ripe and right. Hence, ideological extremity and ethnic politics, coupled with elite competition and ample spaces for the dissemination of hate speech and harmful content on social media platforms, create a conflict aggregating loop that drives affective polarization to the extreme edge.

In its uncharted path toward social transformation, the youth bulge and the mobilization of new young forces in Afghanistan’s society and politics are intermingled with a tangible inter-generational gap and digital divide. In the absence of democratic institutions and positive developments in the political and economic areas that would help accommodation and incorporation of these forces, it presents a threat that could otherwise be its social dynamic for positive change. Youth’s frustration with the long-standing economic inequality and stagnation, social insecurity, and political instability have driven them toward ideological extremity, both those who side with the Taliban and those who oppose the Taliban. Ethnonationalist passions are higher among the youth compared to the older generation, which makes them susceptible to holding more extreme views regarding the political prospects of the country with an intense affective commitment to identity groups. While those among the Taliban are indoctrinated under ideological orientations of radical Islamism, Afghan youth opposing the Taliban are nested in an imagined utopia within the comfort of echo chambers of online homophily, isolating them from the political diversity and ground reality of the country. Therefore, inadvertently, they fall prey to the elite’s machination while being misled by the hyper-availability of social media and the massive flow of misinformation, disinformation, hate, and harmful messages, which turns them into forces of a latent conflict rather than constructive forces of peace and positive change.

In sum, for Afghanistan to move forward, all parties need to work for the deconstruction of affective polarization through the deconstruction of the culture and narrative of violence and inter-ethnic and sectarian enmity. However, we need to recognize that such efforts find less ground in the current political regime that suppresses its opposition voices and does not recognize cultural and political diversity. A robust and constructive international engagement for facilitating intra-Afghan dialogue and peacebuilding is of paramount importance. Historical evidence and past experiences suggest that without an accommodating democratic system of governance that recognizes the sovereignty of the nation and sociopolitical diversity, it is hard to imagine a foundational solution to the current situation and an end to the plight and suffering of the Afghan people.

Therefore, the following recommendations are quintessential for any positive engagement for peace and reconciliation in Afghanistan:

- Technological intervention from social media platforms for robust and effective content moderation would help reduce the amount of hate and harmful content and give moderate voices a chance to build common ground based on shared values and aspirations. This is also important in de-escalating conflict and deconstructing affective polarization, allowing diverse opinions to be heard and discussed in meaningful cross- group communication and interaction.

- In addition, deconstruction of affective polarization requires opening and widening the political and social horizons for positive change, which requires a more effective and robust international engagement for intra-Afghan dialogue and initiation of a peace and reconciliation process. Otherwise, as long as the Taliban’s oppressive monopoly of power continues, deconstruction of affective polarization will not be possible by moderating the content, simply because divisive content is part of a socio-political loop that works through a complex reinforcement mechanism.

- Given that initiating intra-Afghan dialogue and a comprehensive peace and reconciliation process takes time and can be lengthy and complex, track 2 discussions among political elites, parties, and civil society are crucial for highlighting common ground and shared principles. Digital peacetech platforms such as Remish and Pol.is can play a facilitating role in deliberative peacebuilding by generating a new conversation over the future of the country and bridging the gaps.

Acknowledgment

The author conducted the research as a visiting fellow at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and benefited from the generous financial and academic support during the fellowship.

References

Abbas, H. (2023). The Return of the Taliban: Afghanistan After the Americans Left. Yale University Press. https://t.me/HazaraVoiceLibrary

Acerbi, A. (2019). Cultural Evolution in the Digital Age. In Cultural Evolution in the Digital Age. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198835943.001.0001

Allan, N. J. R. (2001). Defining place and people in Afghanistan. Post-Soviet Geography and Economics, 42 (8), 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/10889388.2001.10641186

Asimovic, N., Nagler, J., Bonneau, R., & Tucker, J. A. (2021). Testing the effects of Facebook usage in an ethnically polarized setting. PNAS, 118 (25), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022819118

Bahari, S. (2015, November 15). Ma hama bikarim, az dawlat bizarim. Etilaat Roz. https://www.etilaatroz.com/29576/

Barfield, T. (2010). A Political and Cultural History of Afghanistan. Princetone University Press.

Barth, F. (1998). Pathan Identity and its Maintenance. In Fredrik Barth (Ed.), Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference (pp. 117–124). Waveland Press, Inc.

Bickert, M. (2020). Charting a Way Forward: Online Content Regulation. https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Charting-A-Way-Forward_Online-Content-Regulation-White-Paper-1.pdf

Bose, S., Bizhan, N., & Ibrahimi, N. (2019). Making Peace Possible Youth Protest Movements in Afghanistan: Seeking Voice and Agency (145; Peacework). https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/02/youth-protest-movements-afghanistan

Bradley, M., & Chauchard, S. (2022). The Ethnic Origins of Affective Polarization: Statistical Evidence From Cross-National Data. Frontiers in Political Science, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.920615

Brass, P. R. (1991). Ethnicity and Nationalism: Theory and Comparison. Sage Publications.

Bright, J. (2018). Explaining the emergence of political fragmentation on social media: The role of ideology and extremism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23 (1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmx002

CBS News. (2021, December 19). Full transcript: Hamdullah Mohib on “Face the Nation,” December 19, 2021. CNS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/transcript-hamdullah-mohib-face-the-nation-12-19-2021/

Central Statistics Organization. (2014). The National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2011-12.

Chai, S. K. (1996). A theory of ethnic group boundaries. Nations and Nationalism, 2 (2), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1996.00281.x

Chandra, K. (2005). Ethnic Parties and Democratic Stability. Perspectives on Politics, 3 (2), 235–252. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i288406

Cheng, Z., Marcos-Marne, H., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2023). Birds of a Feather Get Angrier To- gether: Social Media News Use and Social Media Political Homophily as Antecedents of Political Anger. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09864-z

Cookson, J. A., Engelberg, J. E., & Mullins, W. (2023). Echo Chambers. Review of Financial Studies, 36 (2), 450–500. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhac058

de Keulenaar, E., Magalhães, J. C., & Ganesh, B. (2023). Modulating moderation: a history of objectionability in Twitter moderation practices. Journal of Communication, 73 (3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqad015

Díaz, Á., & Hecht, L. (2021). Double Standards in Social Media Content Moderation. https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/Double_Standards_Content_Moderation.pdf

Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? In Public Opinion Quarterly (Vol. 83, Issue 1, pp. 114–122). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz003

Flückiger, M., & Ludwig, M. (2018). Youth Bulges and Civil Conflict. Source: The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62 (9), 1932–1962. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48596881

Gaan, N. (2015). Youth bulge: Constraining and reshaping transition to liberal democracy in Afghanistan. India Quarterly, 71 (1), 16–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974928414554973

Garrett, K. R., Long, J. A., & Jeong, M. S. (2019). From partisan media to misperception: Af- fective polarization as mediator. Journal of Communication, 69 (5), 490–512. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz028

Haqqani, S. A. H. (2022). Al Emarat al Islamiah wa Nizamuha (The Islamic Emirate and Its Organization). Maktab Darul Ulum al-Shareiya.

Hawkins, J. (2009). The Pashtun Cultural Code: Pashtunwali. Australian Defense Force Journal, 180, 16–27. https://search.informit.org/doi/pdf/10.3316/ielapa.201001585

Hecht, M. L., & Ribeau, S. (1984). Ethnic communication: A comparative analysis of satisfying communication. In International Journal of lntercultural Relations (Vol. 8).

Hopkins, B. D. (2008). The Making of Modern Afghanistan. Palgrave.

Hopp, T., Ferrucci, P., & Vargo, C. J. (2020). Why do people share ideologically extreme, false, and misleading content on social media? A self-report and trace data-based analysis of countermedia content dissemination on facebook and twitter. Human Communication Research, 46 (4), 357–384. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqz022

Huntington, S. P. (1968). Political Order in Changing Societies. Yale University Press.

ITU. (2022a). Digital Development Dashboard, Infrastructure and Access in Afghanistan. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Dashboards/Pages/Digital-Development.aspx

ITU. (2022b). Measuring digital development: Facts and Figures. : https://www.itu.int/hub/publication/d-ind-ict_mdd-2022/

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Reviews, 22, 129–146. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. In Public Opinion Quarterly (Vol. 76, Issue 3, pp. 405–431). https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038

Jenke, L. (2023). Affective Polarization and Misinformation Belief. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09851-w

Kamber, T. (2017). Gen X: The Cro-Magnon of Digital Natives. Journal of the American Society on Aging, 41 (3), 48–54. https://oats.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Kamber-Gen-X-2017.pdf

Kemp, S. (2023). Digital 2023: Afghanistan. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-afghanistan

Korotayev, A., Romanov, D., Zinkina, J., & Slav, M. (2023). Urban Youth and Terrorism: A Quantitative Analysis (Are Youth Bulges Relevant Anymore?). Political Studies Review, 21 (3), 548–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299221075908

Kubin, E., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: a systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45 (3), 188–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2021.1976070

Kvam, P. D., Alaukik, A., Mims, C. E., Martemyanova, A., & Baldwin, M. (2022). Rational infer- ence strategies and the genesis of polarization and extremism. Scientific Reports, 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11389-0

Lackey, J. (2021). Echo Chambers, Fake News, and Social Epistemology. In The Epistemology of Fake News (pp. 206–227). Oxford University PressOxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198863977.003.0010

Levo-Henriksson, R. (2007). Media and Ethnic Identity: Hopi Views on Media, Identity, and Communication. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203941492

Lieven, A. (2021). An Afghan Tragedy: The Pashtuns, the Taliban and the State. Survival, 63 (3), 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1930403

Lijphart, A. (1969). Consociational Democracy. World Politics, 21 (1), 207–225. https://about.jstor.org/terms

Már, K. (2020). Partisan Affective Polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84 (4), 915–935. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa060

Mason, L. (2016). A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80 (Specialissue1), 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw001

Mcpherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Miller, D., Costa, E., Haynes, N., McDonald, T., Nicolescu, R., Sinanan, J., Spyer, J., Venkatraman, S., & Wang, X. (2016). How the World Changed Social Media. UCL Press.

Ministry of Economy (MOE). (2021). List or Non-Governmental Organizations. https://ngo.gov.af/publication/Home/National_ngos

Ministry of Justice (MOJ). (2021a). List of Active Associations. https://moj.gov.af/sites/default/files/jamiats4476.pdf

Ministry of Justice (MOJ). (2021b). Registered Political Parties. https://moj.gov.af/en/registered-political-parties

Naroll, R. (1964). On Ethnic Unit Classification. Current Anthropology, 5 (4), 283–312. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2740256

Nojumi, N. (2002). The rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass mobilization, civil war, and the future of the region. In The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region. Palgrave Macmillan.

Nordbrandt, M. (2021). Affective polarization in the digital age: Testing the direction of the relationship between social media and users’ feelings for out-group parties. New Media and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211044393

Nusratty, K., & Crabtree, S. (2023). Digital Freedom Out of Reach for Most Afghan Women. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/471209/digital-freedom-reach-afghan-women.aspx

Olesen, A. (1995). Islam and Politics in Afghanistan. Routledge.

Olzak, S. (1983). Contemporary Ethnic Mobilization. Annual Review of Sociology, 9, 355–374. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2946070

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin Press.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, Part 1. On The Horizon, 9 (5), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

Procter, A. J. (2015). Afghanistan’s Fourth Estate Independent Media (189; Peacebrief ). https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/PB189-Afghanistans-Fourth-Estate-Independent-Media.pdf

Quinn, D., & Gurr T. R. (2003). Self-Determination Movements and Their Outcomes. In Monty G. Marshall & Ted Robert Gurr (Eds.), Peace and Conflict 2003: A Global Survey of Armed Conflicts, Self-Determination Movements, and Democracy. Center for Interna- tional Development & Conflict Management.

Rabushka, A., & Kenneth A. Shepsle. (1972). Politics in Plural Societies: A Theory of Demo- cratic Instability. Longman.

Reiljan, A., Garzia, D., Ferreira Da Silva, F., & Trechsel, A. H. (2023). Patterns of Affective Polarization toward Parties and Leaders across the Democratic World. American Political Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000485

Renström, E. A., Bäck, H., & Carroll, R. (2023). Threats, Emotions, and Affective Polarization. Political Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12899

Rogowski, J. C., & Sutherland, J. L. (2016). How Ideology Fuels Affective Polarization. Political Behavior, 38 (2), 485–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9323-7

Rubin, B. R. (2002). The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System. Yale University Press.

Serpe, R. T. (1987). Stability and Change in Self: A Structural Symbolic Interactionist Expla- nation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50 (1), 44–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2786889

Sharan, T. (2023). Inside Afghanistan: Political Networks, Informal Order, and State Disruption. Routledge.

Smith, A. (1994). The politics of culture: ethnicity and nationalism. In The Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Routledge.

Snajdr, E. (2007). Ethnicizing the subject: domestic violence and the politics of primordialism in Kazakhstan. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.), 13 (3), 603–620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2005.32.2.294

Statcounter. (2022). Social Media Stats Afghanistan: Nov 2021-Nov 2022. https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/afghanistan

Stefanelli, A. (2023). The Conditional Association Between Populism, Ideological Extremity, and Affective Polarization. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 35 (2). https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edad014

Procter, A. J., Mccarty, N., & Bryson, J. J. (2020). Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline. In Sci. Adv (Vol. 6). https://www.science.org

Procter, A. J., Plotkin, J. B., & Mccarty, N. (2021). Inequality, identity, and partisanship: How redistribution can stem the tide of mass polarization. PNAS, 118 (50), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2102140118

Stewart, B., & McGauvran, R. J. (2020). What Do We Know about Ethnic Outbidding? We Need to Take Ideology Seriously. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 26 (4), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2020.1809897

Stryker, S. (2003). Symbolic Interactionism : A Social Structural Version. Blackburn Press.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and inter-group behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1 (2), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

The World Bank. (2020). Individuals using the Internet (% of the population) – Afghanistan. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=AF

Tornberg, P. (2019). How digital media drive affective polarization through partisan sorting.Toda Peace Institute, Policy Brief No. 44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2207159119

Voltmer, K. (2006). The mass media and the dynamics of political communication in pro- cesses of democratization: an introduction. In Mass Media and Political Communication in New Democracies (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

Wafayezada, M. Q. (2023). Hybrid Extremism: Ethnonationalism and Territorialized Islamic Fundamentalism in Afghanistan. Review of Faith and International Affairs, 21 (3), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2023.2235834

Williams, R. M. (1994). THE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC CONFLICTS: Comparative International Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Sociol, 20, 49–79. www.annualreviews.org

Zingher, J. N. (2022). Mass Opinion in Context. In Political Choice in a Polarized America (pp. 24-C2.P75). Oxford University Press, New York. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197630693.003.0002

Zuber, C. I., & Szöcsik, E. (2015). Ethnic outbidding and nested competition: Explaining the extremism of ethnonational minority parties in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 54 (4), 784–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12105

The Author

Dr. Mohammad Qasim Wafayezada is a specially appointed professor of peace and conflict studies at Kanazawa University, Japan. His scholarly pursuits focus on pivotal areas such as peacebuilding, statebuilding, nation building, ethnic politics, and conflict resolution in divided societies. He is the author of Ethnic Politics and Peacebuilding in Afghanistan (2013) and several academic articles and policy papers. As a practitioner, he has served in various governmental positions, including Minister of Information and Culture for the Afghan Republic Government.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org