Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament Policy Brief No.189

Reflections on R2P as a New Normative Settling Point

Ramesh Thakur

May 13, 2024

This Policy Brief is a reflection on the origins, progress, setbacks, and current status of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), the international community’s organising principle for responding to the threat or outbreak of mass atrocity crimes inside sovereign jurisdictions. While the articulation, refinement, institutionalisation, and consolidation of such a norm is one thing, the question remains: has R2P made a difference in practice? This question is addressed by Ramesh Thakur, a former UN assistant secretary-general, and a Commissioner and one of the principal authors of R2P.

Contents

- Background

- Power, Principles, Ideas, and the Normative International Architecture

- Sovereignty and Its Discontents

- ICISS & R2P

- R2P ≠ Humanitarian Intervention

- Refining and Institutionalising the Norm

- Implementation and Non-implementation Controversies

- Structural Intervention Dilemmas in Civil Wars

- R2P is a Global Normative Answer to a Universal Moral Failing

- Assessing and Explaining Success

- Conclusion

I retired from the Australian National University and more or less disengaged from academic debates six years ago.[1] Since then, my contributions have been limited to the occasional op-ed, and an edited volume on the Nuclear Ban Treaty.[2] Because the topic of my talk today[3] is likely to be the defining legacy of my professional life, I accepted this invitation as one final opportunity to reflect on the origins, progress, setbacks, and current status of what in its time was an innovative advance that aimed to fill a critically important normative gap.

The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) is the international community’s organising principle, acting through the authenticated structures and procedures of the United Nations, for responding to the threat or outbreak of mass atrocity crimes inside sovereign jurisdictions. The principle struck a balance between the institutionalised indifference of the international community in the Rwanda genocide of 1994 and unilateral intervention as by NATO in Kosovo in 1999. After adoption by the UN in 2005, R2P became the normative instrument of choice for converting a shocked international conscience into decisive collective action to prevent and stop atrocities; for channelling selective moral indignation into collective policy remedies. In the vacuum of responsibility for the dehumanised victims of mass atrocities, R2P provided an entry point for the international community to take up the moral and military slack. It was the acceptance of the duty of care by all of us who live in zones of safety towards those trapped in zones of danger.

Background

One of the most important developments in world politics in recent decades has been the spread of the twin ideas that state sovereignty comes with both domestic and international responsibilities as well as privileges, and that, alongside the primary state responsibility to protect people threatened by mass-atrocity crimes, there also exists a fallback global responsibility to protect. The 2001 report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) entitled The Responsibility to Protect put these ideas into circulation in the policy and scholarly communities. UN resolutions in and since 2005 have given it further shape and substance.

The justification of NATO action in Libya on the strength of Security Council Resolutions 1970 and 1973, which made explicit reference to the R2P principle, put this particular notion at the centre of discussion of some of the most challenging political dilemmas of our times. As international leaders struggled in vain to find ways to deal with mounting political violence in Syria, and then again with the emergence of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, the idea of R2P was never far below the surface. But since those times it seems to have fallen below the radar, with perhaps the occasional angry tirade against the failure to invoke it in various crises, from the plight of the Rohingyas in Myanmar to the Palestinians in Gaza.[4]

One key element of the context within which the idea of a responsibility to protect took shape was a critical weakness in the normative framework determining how sovereign states should relate to one another and also to international organisations. This weakness arose because of the unsatisfactory nature of ideas about ‘humanitarian intervention’ that had resurfaced.

Another key element was a sequence of events in which ordinary people were brutalised in ghastly ways in various parts of the world. Whilst the Holocaust had already provided an unprecedentedly horrific example of mass murder on an industrial scale, there had been hopes in the aftermath of the Second World War that the new architecture of the United Nations, the development and anathematisation of the idea of genocide, and the capacity of media to expose horrendous acts of cruelty in real time would put a stop to such events. Yet, they persisted and in the post-Cold War period, developments such as ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, and above all the Rwanda genocide of 1994 thirty years ago this month, made it a matter of urgency to find a better way of ‘saving strangers’ [5] and protecting the vulnerable.

Complicating the matter still further, the vocabulary of humanitarianism has been appropriated throughout history to justify political and coercive measures – up to and including the use of force in the service of self-interested geopolitical and commercial motives. Many developing countries were intimately familiar with this as part of their historical encounter with European colonial powers. A grim example of this was provided in Europe itself by Germany in the 1930s, where Nazi Germany frequently sought to justify its expansionism with reference to the need to protect the alleged infractions of the rights and freedoms of ethnic Germans living in contiguous countries like Czechoslovakia and Poland. In more recent times this has been resurrected in the form of Russia and its role in protecting linguistic and ethnic Russians living in kin states in its near abroad in eastern Europe.[6]

After the Second World War, a new framework of norms and rules was developed to deal with the use of force in international relations, a framework centred on the Charter of the new United Nations, in particular Articles 2.4, 39, 41, 42, and 51. The UN Charter codified both the law and the new normative consensus.

However, one crucial problem remained. The US, UK, USSR, France, and China were made permanent members of the Security Council. The no-limits veto power of the P5 ensured the paralysis of the Security Council other than on rare occasions. This raised the question of what was to be done when some horror seemed to require action, but action could not be justified either by reference to self-defence, or alternatively to explicit Security Council authorisation?

An answer came with the idea of ‘humanitarian intervention’ that, although illegal, might be morally justifiable. Various examples of state behaviour were cited from time to time as examples of humanitarian intervention, including the Indian intervention in East Pakistan in 1971 that created Bangladesh as an independent state, the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1978 that resulted in the displacement of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, and the Tanzanian overthrow of Idi Amin in Uganda in 1979. Although many observers welcomed the consequences of these specific actions, others worried about the future risk to the multilateral rules-based global order from the precedent being set of unilateral interventions based on a mix of self-serving and principled considerations, and the attendant risk of amplifying international power asymmetries.

Power, Principles, Ideas, and the Normative International Architecture

Over time the pendulum of human behaviour has swung surely, albeit slowly and in a jagged rather than linear trajectory, from the ‘pure’ power towards the normative end of the arc of history. To paraphrase and update the familiar mantra of Realism, international politics consists of the struggle for the ascendancy of competing normative architectures conducted on two axes. One axis consists of military muscle, economic weight, and geopolitical heft. The second axis consists of values, principles, and norms.

Over the last few centuries, Western ideas and values found expression as ‘universal’ norms and were embedded in the dominant institutions of global governance not necessarily nor solely because they are intrinsically superior, but more importantly behind battleships, missiles, and tanks. That era is fading but leaving considerable turbulence in its wake. And the form, contours, and normative content of the emergent new era remain inchoate.

Over 1989–91, the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the former Soviet Union, and the emergence of Russia as a shrink-wrapped successor state, set in train a cascading set of consequences. With the frozen geopolitical frame unlocked, many local conflicts emerged from the shadow of the Cold War and erupted into complex humanitarian emergencies. As the US-led West was the only grouping capable of alleviating the resulting mass suffering, demands grew correspondingly for the Western powers to ‘do something’. Efforts to intervene based solely on humanitarian considerations where no national interests were engaged lacked sufficient motivation for sustained engagement when difficulties were encountered, as in Somalia in the early 1990s. Therefore, other crises crying out for ‘humanitarian intervention’ were ignored, such as the Rwanda genocide. But interventions were mounted with mixed-motive calculations where geostrategic interests coincided with humanitarian tragedies, as in the Balkans in the second half of the 1990s.

In the process, the North Atlantic community discovered that a defeated Russia could be safely ignored as a military rival even in its Balkans backyard and that its influence in the United Nations system had also greatly waned. In 1999, Russia watched helplessly from the sidelines as its ally, Serbia, was dismembered by NATO, even though Serbia had not attacked any member of NATO that had hitherto been portrayed as a purely defensive alliance. Yet, Moscow neither forgave nor forgot the lesson. Meanwhile although China had begun its astonishingly rapid ascent up the ladder of economic growth and military modernisation, it was still two to three decades away from re-emerging as a comprehensive national power.

The inability of any other state actor or collective grouping to act as a check on the untrammelled exercise of US and NATO military power, combined with communism that was discredited both as a political ideology and as an organising principle for the economy, in turn fostered growing faith in using US military power to refashion the world in its own image, bred exceptionalism in the unipolar moment, and blinded Washington to the concerns, fears, and preferences of others. As Peter Beinart wrote in The Atlantic: ‘The Trump administration’s decision [of May 2018] to openly violate the Iran [nuclear] deal – and demand that Iran negotiate a new one more favourable to the U.S. – is a brazen example of this “rights exceptionalism”’.[7]

Only the United States, it seemed, was permitted to act in material breach of binding international agreements and violate international law. All other actors, including China and Russia as emerging and faded great powers, were still required to abide by accords, conform to global norms, and respect international law. Consider, for example, two speeches by a US president within four months of each other. Speaking at West Point on 28 May 2014, Nobel Peace Laureate Barack Obama insisted: ‘The United States will use military force, unilaterally if necessary, when our core interests demand it’. [8] In his speech to the UN General Assembly on 24 September, he said: ‘all of us – big nations and small – must meet our responsibility to observe and enforce international norms’.[9] The two statements are not compatible and indeed the second was in the context of criticising Russia for unilateral actions in Crimea and Ukraine undertaken in defence of its core interests.

Whoever thought this could be sustained indefinitely notwithstanding the shift in wealth, power, and influence, and in consequence in the geopolitical centre of gravity, from the previously ascendant North Atlantic countries to the Indo-Pacific? As other states become economically and militarily powerful, for example India, their trains of global interests expand and they seek commensurate influence over international political and economic institutions. If the equilibrium of interests proves too rigid and unbending in existing institutions, they look to create new ones more congenial to their interests, organising principles, and value preferences, such as the G20 and BRICS.

Even in the moment of the US unipolar triumph at the end of the Cold War, the Global South comprised a majority in the UN General Assembly and could deny the West the imprimatur of collective legitimacy by using superior numbers. They were motivated to do so because their historical narrative of colonialism was starkly different from that of the major European colonial powers who thought they had exported civilisation to the natives. Anyone who wishes to understand the deep-seated cynicism of many people in the Global South about the self-sustaining belief in an exceptional America and a virtuous West should read The Blood Telegram (2013) by Gary Bass.[10]

Reinforcing that in one of the more important as well as interesting studies of elite perceptions, published by Chatham House, in contrast to Europeans who emphasised America’s historical ‘moral leadership’, many Asian elites view the US as hypocritical, overbearing, arrogant, and disinterested in others’ interests, aggressively pushing its own policy priorities instead.[11]

Sovereignty and Its Discontents

The preceding section describes a shifting global order with respect to economic weight, military power, and diplomatic heft. As applied to international interventions—Can it ever be justified? If so, by whom, under whose authority and with what conditions and safeguards? —the legal principle over which the shift collided was state sovereignty as a shield against unilateral Western humanitarian intervention.

Sovereignty is the bedrock organising principle of modern international society and faith in it was strongly reaffirmed by the large number of countries as they regained their independence from colonial bondage. Their attachment to sovereignty is both deeply emotional, reflecting the lingering trauma of their colonial experience, and also functional. The state is the cornerstone of the international system and state sovereignty provides order, stability, and predictability in international relations.

In the meantime, however, as the world steadily became a global village under the impact of rapid developments in communications and transportation technology, the human rights norm also deepened and spread outwards from the Euro–Atlantic core to the farthest reaches of the increasingly interconnected international system. In the use of force within and across borders, states have had to conform increasingly to international standards and normative benchmarks. The history of the twentieth century was in part the story of a twin- track approach to tame impulses to armed criminality by states in the use of force domestically (to commit atrocities against their own people) and internationally (to commit aggression against other countries). Cumulatively, these attempted to translate a newly internationalised human conscience into a new normative architecture of world order.

This produced normative dissonance between the norms of non-intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign states and the abusive practices and humanitarian atrocities perpetrated by some brutish thug-rulers on their own peoples shielding behind that norm. A critical gap developed when victims of state-sanctioned atrocities needed international military force to protect them, but the authenticated organisations were too timid or paralysed to act decisively and in time.

When some states defied the norm of non-intervention in efforts to protect the victims of mass atrocity crimes, their claimed emerging norm of ‘humanitarian intervention’ collided with the existing norm of non-intervention. The international policy community split between the major powers and the majority of states from the Global South. Under the impact of contrasting experiences in Rwanda and Kosovo, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan urged member states to come up with a new consensus on the competing visions of national and popular sovereignty and the resulting ‘challenge of humanitarian intervention’.

Institute of International Affairs, May 2014).

ICISS & R2P

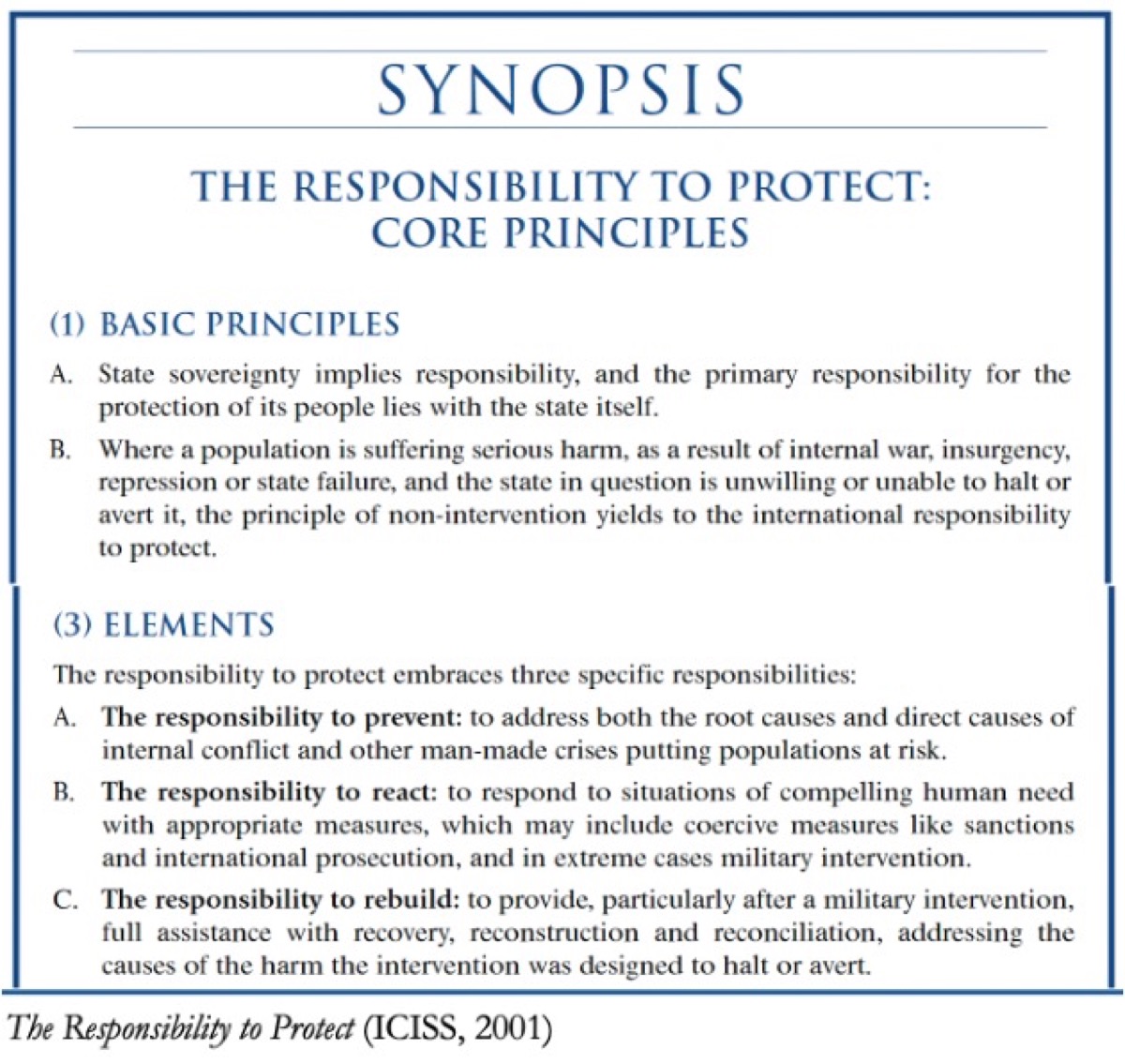

The combination of problems crying out for attention set the scene for conceptual innovation and normative entrepreneurship. The Responsibility to Protect met the challenge. The report is 91 pages long and is supplemented with a substantial research volume, published at the same time, that runs to 410 pages. The key elements are summarised in the preliminary synopsis shown above at p. xi.

It offered the seductive promise of a new normative settling point on the contested challenge of how best to respond effectively to humanitarian atrocities with actions that were both legal and legitimate. In effect, ICISS inverted the paradigm of state–citizen relations on rights and responsibilities. Henceforth citizens were to be treated as the bearers of rights while states had to accept responsibilities towards the people and the international community. This was done by reconceptualising sovereignty as responsibility that was located in the state itself in the first instance, but in the international community as represented by the United Nations as a residual responsibility.

The principle was endorsed unanimously by world leaders meeting at the United Nations summit in 2005:

Affirming individual state responsibility to protect populations, member states declared they were ‘prepared to take collective action, in timely and decisive manner, through the Security Council … and in cooperation with relevant regional organisations as appropriate, should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities are manifestly failing to protect their populations’ – 2005 World Summit Outcome, paras. 138–9.

The ICISS formulation of the three symbiotically interlinked responsibilities embedded in the overall R2P principle are inflection points along the arc of a conflict curve: the responsibility to prevent atrocities; the responsibility to react to calls on our internationalised human conscience to situations requiring compelling human protection; and the responsibility to rebuild robust and resilient peace through enduring structures of governance that blend the co-equal imperatives of justice and order.

By realigning the emerging global political norm to existing categories of international legal crimes, the 2005 reformulation of the ICISS language added clarity, rigour, and specificity, limiting the triggering events to war crimes, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. The Secretaries-General’s special reports on R2P helped to sustain and consolidate the international consensus. Since then, R2P has progressed along three parallel tracks in the UN system: in numerous UNSC resolutions and presidential statements, successive reports of the Secretary-General, and annual debates in the General Assembly on these reports. In addition, it has been progressively institutionalised in the UN system and in some national governments and widely disseminated and promoted by civil society organisations.

R2P ≠ Humanitarian Intervention

The key innovation in 2001 was the re-conceptualisation of ‘humanitarian intervention’ as R2P; everything else in this discourse flows from that distinction. Contrary to the criticism that R2P was merely old wine in a new bottle, the differences between them are real and consequential:

- Conceptually, ‘humanitarian intervention’ defines relations between different states in a hierarchical power structure. By contrast, R2P upends state-citizen relations internally and defines the distribution of authority and jurisdiction between states on the one side and the international community on the other.

- Normatively, ‘humanitarian intervention’ rejects non-intervention and privileges the perspectives and rights of the intervening states. R2P addresses the issue from the perspective of the victims, sidesteps non-intervention, reformulates sovereignty as responsibility, and links it to the human protection norm.

- Procedurally, R2P can only be authorised by the UN whereas ‘humanitarian intervention’ is open to unilateral interventions.

- Operationally, protection of victims from mass atrocities requires distinctive guidelines and rules of engagement and different relationships to civil authorities and humanitarian actors, always prioritising the protection of civilians over the safety and security of the intervening troops.

- Politically, the visceral hostility of a large number of former colonised countries to ‘humanitarian intervention’ is explained by the historical baggage of rapacious exploitation and cynical hypocrisy. Insistence on the discredited and discarded discourse of ‘humanitarian intervention’ by self-referencing scholars amounts to an in- your-face disrespect to them, to ICISS, and to all the various groups of actors who have embraced R2P as an acceptable replacement.

Refining and Institutionalising the Norm

The 2005 UN world summit outcome resolution clarified and narrowed the scope of R2P by limiting it to four crimes: genocide, ethnic cleansing, other crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The nature of the new principle-cum-norm was further refined in the Secretary- General’s inaugural special report on R2P in 2009 which reformulated R2P in the language of three distinct ‘pillars’: a state’s responsibility not to commit such mass atrocity crimes or allow them to occur (‘Pillar One’); the responsibility of other states to assist those lacking the capacity to so protect (‘Pillar Two’); and the responsibility of the international community to respond with ‘timely and decisive action’ – including ultimately with coercive military force, but only if authorised by the UN Security Council – if a state is ‘manifestly failing’ to meet its protection responsibilities (‘Pillar Three’).

Today, although R2P is no longer seriously contested in the policy community as principle, controversy continues in the academic community over implementation and its normative status on two opposite fronts: it is too restrictive and offers too little protection against gross abuses of the human rights norm by powerful national leaders; and it is too permissive and fails to provide robust enough safeguards against self-interested abuses by powerful countries of the non-intervention norm. The post-intervention instability, volatility, lawlessness, and killings in Libya only strengthened the criticism.

Nevertheless, it is equally noteworthy that there has been no attempt in UN circles to rescind R2P. The drive to institutionalisation began with the creation of a new post, at the rank of Assistant Secretary-General, of a Special Adviser on R2P to the Secretary-General. Although the post remains unfunded, at least it is not unfilled and there have been six such office holders to date (Table 1).

Table 1: Special Advisers to the UNSG on R2P

| 2008–12 | Edward Luck |

|---|---|

| 2013–15 | Jennifer Welsh |

| 2016–18 | Ivan Šimonović |

| 2019–21 | Karen Smith |

| 2022-–23 | George Okoth-Obbo |

| 3.2023– | Mô Bleeker |

In addition, there have been scores of Security Council and Human Rights Council resolutions (Table 2). There are more than 60 R2P focal points,[12] comprising senior level national representatives, in New York, Geneva, and national capitals.

The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, established in 2008, has offices in New York and Geneva, acts as the secretariat for the Global Network of R2P Focal Points and the UN Group of Friends of R2P, has published a Manual for R2P Focal Points, [13] publishes regular R2P Monitor and Atrocity Alerts and engages in training programs as well as policy advocacy. The Asia Pacific Centre for R2P at Queensland University promotes the principle in Asia and the Pacific through research and policy dialogue.[14]

Table 2 – R2P as a normative force: UN Security Council, General Assembly, and Human Rights Council resolutions, 2006–23

| Security Council resolutions |

General Assembly resolutions |

Human Rights Council resolutions |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 2007 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2008 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 2010 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2011 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| 2012 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 2013 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| 2014 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 16 |

| 2015 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| 2016 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 19 |

| 2017 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 22 |

| 2018 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 22 |

| 2019 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 14 |

| 2020 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 14 |

| 2021 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 18 |

| 2022 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 15 |

| 2023 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 13 |

| Total | 98 | 31 | 76 | 205 |

Source: Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect (http://www.globalr2p.org)

On the academic side, there have been handbooks, numerous books, innumerable articles, and a dedicated and well-regarded journal—The Global Responsibility to Protect—devoted to R2P. In sum, the Responsibility to Protect is still very much part of the contemporary international normative and policy debate on the lawfulness and legitimacy of using force to protect at-risk populations inside sovereign jurisdictions.

Implementation and Non-implementation Controversies

The articulation, refinement, institutionalisation, and consolidation of the norm is one thing. The fact remains that the commission was set up to deal with a problem in the real world: the killings of large numbers of people by brutal rulers and the refusal of many other peoples around the world to stand by and watch helplessly, constrained by the principle of state sovereignty that had been corrupted effectively into a tyrant’s charter. In other words, for all its rhetorical flourishes, has R2P made a difference in practice? Here the answer is far more ambiguous.

Libya

Libya marks an important milestone on the journey to tame atrocities on their own people by tyrants, initially demonstrating the mobilising power of R2P as a new norm but then showing how easy it was for NATO powers to abuse UN authorisation and the resulting backlash from key players. The R2P consensus on Libya was damaged by the way in which NATO was widely seen beyond the West to have exploited the enabling licence function while ignoring the equally important restrictive leash function of Resolution 1973. Consequently, the record of NATO actions in Libya marked a triumph for R2P but also raised questions about how to prevent the abuse of UN authority to use international force for purposes beyond human protection.

Hardeep Singh Puri, the Indian Permanent Representative on the Security Council at the time (and now a cabinet minister), is clear in his mind that the ‘passage of Resolution 1973 would have been jeopardised if regime change had been specifically mentioned in the text’ – yet no sooner had the resolution been adopted than regime change became the all- consuming goal.[15] As well, while killing Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi helped NATO to win the war, it may have cost them the peace.[16]

Resuscitating the Responsibility to Rebuild

The more important explanation for losing the peace is the failure to pay attention to the needs of Libya after the military intervention that defeated the Gaddafi regime. The 2009 three-pillar frame of reference is now overwhelmingly accepted by the UN community. The coercive end of R2P is associated most strongly with Pillar Three, but the latter is not restricted solely to coercive tools, both military and non-military. Rather, even in Pillar Three, the default first response is peaceful means while forceful means is the option of last resort. The prevention and reaction components of the original ICISS formulation were endorsed and reaffirmed by the UN in 2005, but the third component, namely the responsibility to reconstruct and rebuild after intervention, got diluted in the reformulation into the three pillars framework. President Obama later was to blame the post-intervention Libyan mess on the Europeans who, ‘given Libya’s proximity’, should have been more ‘invested in the follow-up’.[17]

Syrians Paid the Price of R2P Failings in Libya

One important result of the gaps in understanding, communication, and accountability was a split in the international response to the worsening crisis in Syria. In 1999, many argued that although NATO’s bombing of Serbia Kosovo may have been illegal under the UN Charter, it was legitimate as a humanitarian intervention. In an ironic symmetry, NATO actions in Libya in 2011 were deemed by most developing countries to have been legal as they were UN-authorised, but illegitimate in implementation for exceeding the mandate.

The post-Libya intervention refusal by Russia and China to cooperate in robust resolutions against President Bashar al-Assad’s brutal crackdown in Syria led to a widespread perception that inaction on Syria proved the hollowness of R2P as an inherent flaw. Roland Paris argued that the core explanation for the failures in Libya were structural weaknesses in the R2P normative architecture.[18] But his analysis conflated the structural dilemmas inherent in any contemporary use of international force into a central dilemma of R2P.[19] The real question is: does R2P make the structural dilemmas more or less acute? In no case does R2P worsen the dilemma; in most cases it makes the dilemma less acute.

Structural Intervention Dilemmas in Civil Wars

The dilemma confronts the international community at both its starkest and also its most divisive in the context of civil wars. And the international divisions on this typically congeal along the North-South divide. This had already been demonstrated in the first decade of the new millennium in Sri Lanka. As its 26-year brutal civil war came to a bloody end in May– June 2009, the world was gravely concerned over the fate of civilians caught in the crossfire between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE, commonly called the Tamil Tigers) and Sri Lanka’s defence forces. According to UN estimates, some 7,000 civilians had died just in 2009. Up to 80,000 people had been killed in the civil war in all.

The LTTE had grown powerful enough to have its own navy and air force as well as army in de facto occupation of a large chunk of territory. Among the most ruthless terrorist organisations, and designated as such by more than thirty countries in 2009, it had pioneered the use of women suicide bombers and invented the explosive suicide belt. It had assassinated an Indian prime minister and a Sri Lankan president, and killed many civilians, including Tamils. It recruited child soldiers and often raised funds from the Tamil diaspora community through extortion. There was some basis for the government’s claim therefore that post-conflict recovery and progress was not possible until the Tigers had been decisively defeated on the battlefield and eliminated as a military force.

In the final stages of the war, civilians were held against their will by the Tigers, not the army. Many who tried to flee were shot by the Tigers. Tellingly, there were no reports of civilians trying to flee from the Sri Lankan forces to the Tigers. A movement that began as the protector of the nation’s oppressed Tamil minority had mutated into their killers. While Western countries criticised the government’s military offensive and called for restraint and cease-fires, China provided arms and diplomatic cover for the government to complete the offensive. Most developing countries shared the assessment that ‘the West had no business trying to dictate peace terms to the legitimate government of the island, faced with an astonishingly brutal insurgency’.[20]

These considerations help to explain the outcome of the Human Rights Council deliberations in Geneva. [21] Western countries tabled a censorious resolution calling for unfettered access to 270,000 civilians detained in government-run camps and an investigation of alleged war crimes by both sides. China, Cuba, Egypt, and India were among

29 developing countries to support the alternative Sri Lanka-sponsored resolution describing the conflict as a domestic matter that did not warrant ‘outside interference’, praising the defeat of the Tigers, condemning the rebels for using civilians as human shields, and accepting the government’s argument that aid groups should be given access to the detainees only ‘as may be appropriate’. While Colombo was jubilant, Western diplomats and human rights officials were said to be shocked by the outcome at the end of the acrimonious two-day special session, saying it called into question the whole purpose of the Human Rights Council.

Eight Dilemmas

Looking back at the Sri Lankan example and the lack of any meaningful military action to protect civilians in Syria in and since 2011, there are a total of eight structural intervention dilemmas inherent in civil wars:

- Most countries of the world would strongly resist the claim that a state—which in practice means the recognised government of the day—is prohibited from employing force to fend off armed challenges to its authority. Many would also worry about the potential for opposition and secessionist groups elsewhere in the world being encouraged to take up arms against their governments.

- Most civil wars are characterised by confused facts and shared culpability. All sides deliberately manipulate and misuse casualty figures through casual elision, for example implying that one side is responsible for the total casualty toll.

- With regard to chemical weapons use—a qualitative escalation that does cross the ‘atrocity threshold’—there is a further problem. Even if incontrovertible evidence exists to prove the fact of chemical weapons having been used, the forensic examination to establish which agents were used, what their origins might have been, and how they were delivered, before assessing which conflict party might have used them based on the first set of conclusions, is time consuming and requires reasonably prompt access to the site(s) and victims of attacks. But by then it becomes correspondingly harder to mobilise domestic and international sentiment in support of robust military or other punitive action.

- Amidst the confusion of the fog of civil wars where culpability for atrocities is spread among multiple actors, it is nonsensical for outsiders to intervene against several opposing conflict parties in proportion to their degree of culpability. But to intervene against only one conflict party amounts to a partial use of force.

- If interventions are to be guided by an honest appraisal in advance of the balance of consequences, then, bearing in mind that any use of force can produce unintended and perverse consequences, it is impossible to be confident that forceful outside action would not inflame an already volatile situation.

- Diplomatic ennui is often the result of pronounced intervention fatigue.

- There is typically a clash of norms. To the non-West rest, enforcing humanitarian norms inside another country’s sovereign jurisdictions means flouting higher-order global norms on restrictions on the threat and use of force internationally. Those norms are critical to most countries’ national security and international stability. China and Russia (plus India and many others from the Global South) are strongly opposed to authorisation without host-state consent, insist that the continuation and deterioration of civil wars owe as much to rebel intransigence and tactics, and will veto any resolution that could set in motion a sequence of events leading to a Libya-style military operation aimed at regime change.

- Of course, in mixed-motives situations that are typical in world affairs, there are also commercial and geopolitical calculations entangled in any local conflict. Conversely, opposition to intervention also reflects mixed motives. Many countries dislike intrusions into sovereign affairs and fear an intensification-cum-internationalisation of an internal civil war if external troops are injected. They prefer measures to calm the situation, not inflame it further and also have concerns about the moral hazard of outside interventions. They firmly reject any UN right to impose political settlements on sovereign societies.

R2P is a Global Normative Answer to a Universal Moral Failing

The political impasse over coercive R2P intervention is often explained with reference to North–South schisms. Yet R2P is not and ought not to be a North–South issue. The persistent criticism, that R2P is a neo-colonial updated version of the old White Man’s burden, can itself be racist in assumptions and consequences.

- It denies agency to developing countries, insisting they can only be victims, and adds fuel to their sense of grievance.

- It would deny to peoples of developing countries the benefits of good governance that Westerners take for granted,[22] preferring either to leave them to the tender mercies of thugs masquerading as government leaders, or to leave any efforts to alleviate their suffering to the ad hoc geopolitical calculations of powerful Western countries rather than to globally validated norms and due process.

- It ignores the origins of R2P in the demands for protection by atrocity victims in both Africa and Europe and the norm entrepreneurship of people from the Global South in developing the principle, including Mohammed Sahnoun and Francis Deng.

- It also ignores the rich history of indigenous traditions in many parts of Asia and Africa that hold that rulers owe duties for the safety, welfare, and protection of subjects in return for the latter’s allegiance.

Consider the two heavyweight countries in the Global South. Notions of responsibility and the corollary concept of responsible governance have deep roots in Chinese traditions of statecraft and corresponding visions of world order.[23] In turn this suggests that ‘responsible protection’ [24]resonates in Chinese political thought and could conceivably anchor its engagement with global governance.

Similarly, the Hindu-Buddhist concept of dharma—the code of right conduct based on duty —applies to monarchs as much as to subjects. The companion notion of rajdharma means duty of rulers. In 2002, the pro-Hindu Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was in power in the state of Gujarat as well as federally in New Delhi. Gujarat’s Chief Minister Narendra Modi was widely blamed for not instituting effective measures to protect up to 2,000 Muslims who were killed in anti-Muslim riots that erupted when a group of Hindu pilgrims were deliberately burnt alive in a railway carriage. It was a classic R2P case of a mass atrocity due to the responsible government being unable or unwilling to institute effective preventive and reactive measures. Appearing on a dais with Modi and speaking in Hindi, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the Indian prime minister at the time, pointedly reminded Modi of every ruler’s rajdharma.[25]

The Genocide Convention converted the moral revulsion of the Holocaust—a failure of Western civilisation—into a binding universal norm. The two humanitarian crises that most drove the push for R2P were the Rwanda genocide in 1994 and the Balkans atrocities bookended by the Srebrenica massacre in 1995 and the Kosovo intervention in 1999; one African, the other European. [26] R2P is a global norm that, in the allocation of solemn responsibilities of protection, does not discriminate on grounds of nationality, race, or religion, but applies equally to all. As such, it speaks eloquently to the highest UN ideals of international solidarity.

By contrast, the theory and practice of sovereignty is decidedly European in origin and flavour. The major European colonial powers acquired far-flung overseas territories while also intervening against nearby small states on a variety of pretexts. Clearly, Westphalian principles of sovereignty were no bar to such interventions even at the height of this order.

Conversely, as the US-led West’s capacity and will to defend the principles and institutions of the post-1945 liberal international order diminish, the rising powers too will be tempted to intervene across borders and should be subject to global normative restraints. Most countries have been just as suspicious of Russian attempts to appropriate R2P’s mantle of legitimacy in its ‘near abroad’ in eastern Europe (Georgia, Ukraine) as they were of claims of humanitarian intervention in Kosovo and Iraq. All major powers resist the leash functions of laws and norms, including R2P, precisely because laws and norms aim to ‘Gulliverise’ the brute exercise of power.

Assessing and Explaining Success

What counts as success for an international commission? Ideational impact is shown in the generation of new ideas that reshape the existing discourse on the topic. Normative success would come by promoting a new standard of behaviour. Operational success would be indicated by setting new action agendas and changing the prevailing patterns of behaviour. Institutional success would be shown by the creation of new institutions or the reconfiguration of existing ones.

Must a panel demonstrate impact on all these measures, or will one alone suffice to consider it to have been successful? And how much time-lag is permissible in attributing results to commission recommendations? It is worth emphasising that independent bodies, precisely because they are not official, are advisory only and lack executive decision-making authority. In addition, unless their contributions are openly acknowledged, it may be difficult to trace their lineage in the creation of new norms, practices, and institutions.

Attributes and factors that condition and determine the success and failure of high-level commissions include:

- Structural and operational features;

- The quality of leadership provided by the chairs;

- The breadth, depth, and diversity of expertise of panel members;

- The organisation of adequate financial and personnel resources to enable the necessary research and consultations to be undertaken;

- Mission clarity and focus;

- The full range of follow-up dissemination, advocacy, and championing of the recommendations.

While their operational impact can be diffuse, uncertain, and spread thinly over considerable periods of time, they can be important agents of change in global governance for projecting the power of ideas and processing them into new and improved policy, normative, institutional, and operational outcomes. For that reason, high-level international panels and commissions will continue to be set up as instruments for improving deficient governance norms, arrangements, and practices to tackle important and urgent problems. At the same time, history suggests that fewer rather than more will succeed, and even the successful will depend on fortune smiling on them with respect to some matters that are beyond control.

Conclusion

The main point of a new norm is not merely to promote the adoption of a new organising principle of world order to address a particular issue, but to reshape international behaviour by altering state practice. All controversies, shortcomings, and flaws notwithstanding, R2P has a secure future because its origin was essentially demand and not supply driven and the demand for it is unlikely to disappear. From the different theatres of the killing fields in Africa, to the brutality of the war waged by and against the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka and the actions of Islamist insurgents and counter-insurgency operations from Afghanistan through the Middle East to North Africa, the norms of international law, international humanitarian law, and international human rights law seem to have suffered serial reverses.

World order will remain organised around the sovereign state as the basic entity. Some states will continue to exhibit the worst of human nature and engage in atrocities. Others, driven by the better angels of human nature, will want to respond and help innocent victims. Acceptance of the responsibility to protect norm no more guarantees ‘humanitarian intervention’ than its non-existence had foreclosed it as a tool of individual and collective statecraft. Often, disappointing results reflect the failure to utilise other measures in the prevention and response toolbox, such as international humanitarian law and the International Criminal Court, rather than a failure to use coercive force. Increasingly, they reflect also the failure to reform the Security Council with respect to composition, permanent membership, and procedures, despite multiple efforts to do so.

R2P does not resolve all the dilemmas of how outsiders can provide timely, decisive, and effective assistance to all groups in need of protection. It may be deep but remains so narrow that many areas beyond the four atrocity crimes fall outside its scope. It is subject to Security Council veto and paralysis. The most common explanation for the failure to take effective human protection action is the inability to satisfy the balance of consequences test, particularly against the logistical and other practical difficulties of using force in local conflict theatres and the likely damaging consequences for humanitarian relief operations and the fragile peace process.

Even so, R2P is not a principle or norm in search of a self-validating crisis, but an attempt to find new consensus on a rare but recurring problem. The real choice is not if there will or should be any intervention, but whether the intervention will be ad hoc or rules based, unilateral or multilateral, and divisive or consensual. By its very nature, including unpredictability, unintended consequences, and the risk to innocent civilians caught in the crossfire, warfare is inherently brutal: there is nothing humanitarian about the means.

This is why good intentions are not a magical formula by which to shape good outcomes in foreign lands. R2P will help the world to be better prepared—normatively, organisationally, and operationally—to deal with crises of humanitarian atrocities as, when, and wherever they arise, without guaranteeing good outcomes. However, the prospects of success can be enhanced and the controversy surrounding interventions can be muted if they are based on an agreed normative framework. R2P speaks to these concerns and requirements and while inevitably it will be tweaked, it is unlikely to be discarded in the foreseeable future. The risks of perverse consequences are only too real. The use of military force must always— always—be the option of last resort (conceptually, not sequentially), not the tool of choice for dealing with threatened or occurring atrocities. Equally, however, it must be the option of last resort; it cannot be taken off the table.

NOTES

[1] My last academic contributions, written on this topic, were Ramesh Thakur, ‘Global Justice and National Inter- ests: How R2P Reconciles the Two Agendas on Atrocity Crimes’, Global Responsibility to Protect 11:4 (2019), pp. 411–34; and Ramesh Thakur, ‘Kofi Annan, Africa, and the Responsibility to Protect’, The Baobab (A Journal of the Council on Foreign Relations–Ghana)1:1 (2020), pp. 24–45. The writing in both instances was completed shortly before retirement.

[2] Ramesh Thakur, ed., The Nuclear Ban Treaty: A Transformational Reframing of the Global Nuclear Order (Lon- don: Routledge, 2022).

[3] This is the text of a public lecture delivered at Colgate University, Hamilton, New York, 15 April 2024.

[4] Ramesh Thakur, ‘Myanmar pleads for the world to honour the responsibility to protect’, The Strategist, 6 April 2021, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/myanmar-pleads-for-the-world-to-honour-the-responsibility-to-protect/; Abdelwahab El-Affendi, ‘Where is the ‘responsibility to protect’ in Gaza?’, Al Jazeera, 31 October 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/10/31/where-is-the-responsibility-to-protect-in-gaza.

[5] Nicholas J. Wheeler, Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society (Oxford: Oxford Uni- versity Press, 2003).

[6] See Walter Kemp, Vesselin Popovski and Ramesh Thakur, eds., Blood and Borders: The Responsibility to Protect and the Problem of the Kin-State (Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 2011).

[7] Peter Beinart, ‘The Iran Deal and the Dark Side of American Exceptionalism’ The Atlantic, 9 May 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/05/iran-deal-trump-american-exceptional-ism/560063/.

[8] ‘Remarks by the President at the United States Military Academy Commencement Ceremony’, 28 May 2014; http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/05/28/remarks-president-united-states-military-academy-commencement-ceremony.

[9] ‘Remarks by President Obama in Address to the United Nations General Assembly’, 24 September 2014; http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/24/remarks-president-obama-address-united-nations-general-assembly.

[10] Archer Blood was the US Consul General in Dhaka at the time, hence the title of the book.

[11] Xenia Dormandy with Joshua Webb, Elite Perceptions of the United States in Europe and Asia (London: Royal)

[12] https://www.globalr2p.org/the-global-network-of-r2p-focal-points/

[13] http://www.globalr2p.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/R2P-Focal-Points-Manual-6-Feb-2024-FINAL.pdf

[14] Disclosures: I was a founding member of the international advisory board of the Global Centre until my move back to the ANU in Canberra and a founding patron of the Asia-Pacific Centre until my professorial retirement.

[15] Hardeep Singh Puri (India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations while India was on the Security Council in 2011–2012), Perilous Interventions: The Security Council and the Politics of Chaos (Noida: HarperCol- lins India, 2016), 91–92.

[16] Arash Heydarian Pashakhanlou, ‘Decapitation in Libya: winning the conflict and losing the peace’, The Wash- ington Quarterly 40:4 (2018): 135–49.

[17] Quoted in Jeffrey Goldberg, ‘The Obama Doctrine’, The Atlantic, April 2016,http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/.

[18] Roland Paris, ‘The ‘Responsibility to Protect’ and the Structural Problems of Preventive Humanitarian Intervention’, International Peacekeeping 21:5 (2014): 569–603.

[19] Ramesh Thakur, ‘R2P’s ‘Structural’ Problems: A Response to Roland Paris’, International Peacekeeping 22:1 (2015), pp. 11–25.

[20] Peter Popham, ‘How Beijing won Sri Lanka’s civil war’, The Independent on Sunday (London), 23 May 2010.

[21] Catherine Philp, ‘Sri Lanka forces West to retreat over ‘war crimes’ with victory at UN’, The Times, 28 May 2009.

[22] Or at least they used to. I am no longer so sure of this by now.

[23] Pichamon Yeophantong, ‘Governing the world: China’s evolving conceptions of responsibility’, Chinese Jour- nal of International Politics 6:4 (2013): 329–64.

[24] Ruan Zongze, ‘Responsible Protection: building a safer world’, China International Studies (May/June 2012): 19–41.

[25] The video is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJBItuHzUR0.

[26] See Ramesh Thakur, ‘Rwanda, Kosovo and the International Commission on Intervention and State Sover- eignty’, in Alex J. Bellamy and Tim Dunne, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Responsibility to Protect (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 94–113.

The Author

Ramesh Thakur, a former UN assistant secretary-general, is emeritus professor at the Australian National University and Fellow of the Australian Institute of International Affairs. He is a former Senior Research Fellow at the Toda Peace Institute and editor of The nuclear ban treaty: a transformational reframing of the global nuclear order.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org