Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament Policy Brief No.183

Ten Take-Aways on Russia’s War and Five Ideas for the Future of Ukraine and Beyond

Herbert Wulf

February 06, 2024

This Policy Brief discusses the Ukraine war which is now entering its tenth year. Two years ago, President Vladimir Putin announced the so-called “special military operation”. There is no end in sight. To end suffering and destruction it is necessary to think about pathways to peace. How to end the war or at least achieve a ceasefire? What are the most important results of this war so far? Here are the ten key results of the war and five ideas for a possible way out.

Contents

- Ten Take-aways

- 1. Violation of international law and war crimes

- 2. Bogged down in trench warfare

- 3. Collapse of the European security architecture

- 4. Tough sanctions

- 5. Solidarity of NATO and EU

- 6. Destruction and demoralisation in Ukraine

- 7. Mobilisation of resources in Russia: Towards a war economy

- 8. Global impact

- 9. Global rearmament

- 10 .Side-lined UN

- Five Ideas for a Way to End This War

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world…

William Butler Yeats (1865 – 1939)

The future depends on what we do in the present.

Mahatma Gandhi (1869 – 1948)

The Ukraine war has now entered its tenth year. Two years ago, President Vladimir Putin announced the so-called “special military operation”, an invasion of large parts of Ukraine.[1] There is no end in sight. Russia's so-called special military operation has failed, but the Ukrainian counteroffensive did not really get off the ground in 2023 either. Eastern Ukraine is a field of rubble and many buildings and parts of the infrastructure throughout Ukraine have been destroyed. Nevertheless, plans for Ukraine were presented at reconstruction conferences; money was raised from state and private investors. But this alone is not a secure basis for recovery. To end suffering and destruction it is necessary to think about pathways to peace. How to end the war or at least achieve a ceasefire? At the moment, it looks as if the war could continue for years. In the West, there is great scepticism that peace negotiations could take place in the foreseeable future. Russian President Vladimir Putin repeatedly emphasises, despite heavy losses, that he wants to win the war and subjugate Ukraine. Now the war is entering its tenth year and the warring parties and their allies show no signs of compromise and possible consensus. In the apocalyptic scenarios, even a third world war and the use of nuclear weapons are not ruled out. What are the most important results of this war so far? Here are the ten key results of the war and five ideas for a possible way out.

Ten Take-aways

1. Violation of international law and war crimes

The Russian Federation's attack on Ukraine is a violation of international law. This was already the case in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea. There is no doubt that the attacks on civilian targets violate international humanitarian law, which obliges warring parties to provide the greatest possible protection for civilians. The acts of violence committed against the population have now reached a new dimension. In view of the disturbing images in Bucha and elsewhere, serious crimes under international law are evident, despite the Russian government's claims to the contrary. In October 2023, an Independent International Commission of the United Nations came to the following conclusion: „The collected evidence further shows that Russian authorities have committed the war crimes of wilful killing, torture, rape and other sexual violence, and the deportation of children to the Russian Federation.”[2]

Comprehensive investigations are likely to show that Russian authorities will be responsible for a range of crimes: war crimes, crimes against humanity, alleged genocide, and the crime of aggression. But there are also indications of war crimes committed by Ukraine. The UN report mentions “three incidents in which violations of human rights had been committed by Ukrainian authorities and is further investigating these and other allegations of such violations.” [3] Overall, however, the UN Inquiry Commission accuses Russia of a significantly larger number and range of potential human rights violations and war crimes than Ukraine. The report states that it is gathering more and more evidence that the Russian army is also torturing and attacking civilians and “that Russian authorities have used torture in a widespread and systematic way in various types of detention facilities which they maintained.”[4]

There are serious limits to international prosecution when it comes to states that, like Russia, evade any accountability mechanisms. It will be difficult, if not impossible, to hold President Vladimir Putin and his supporters accountable. To have a legal handle on the war crimes, it would be necessary to set up a special tribunal, similar to the war crimes tribunal in Yugoslavia or the Nuremberg tribunal after the Second World War. Neither Ukraine nor the Russian Federation is a State party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). But the UN report nevertheless concludes: “The Rome Statute and its Elements of Crimes provide detailed elements for some of the alleged crimes. Where the Court was found to lack jurisdiction, the Commission applied elements of crimes within the Rome Statute so long as they reflected customary international law.”[5]

2. Bogged down in trench warfare

The two most important military and foreign policy objectives of Russia`s President Vladimir Putin failed completely: : he could neither stop NATO's eastward expansion nor could the Russian military overthrow the Ukrainian government and sustain occupation of all parts of Ukrainian territory, and/or install a more compliant government. NATO, the transatlantic alliance, has with the admission of its new members Finland and Sweden moved even closer to Russia and the expected “Blitzkrieg” success in Ukraine failed to materialise in the early days of war. A first Ukrainian counteroffensive took Russia’s military by surprise, but the second counteroffensive in 2023 stalled for months. This conflict has turned into a war of attrition. It seems that none of the warring parties can gain the upper hand. It is difficult to see a military victory in the war.

There were disappointments on both sides. After Russia invaded in February 2022, Putin, and much of the world, expected that his military would quickly march to Kyiv and topple Ukraine’s government. Already in the first days of the war it became clear that this Russian war aim failed. Putin had hoped that NATO allies would provide only limited support to Ukraine through arms deliveries and military advice. This hope was also deceptive, even though many governments in the EU found it difficult (and in some cases still do) to provide massive military support to Ukraine.

Shortly after the start of the war, Russian forces were on the verge of collapse. But this did not happen either. On the contrary, the second half of 2023 was disappointing for Ukraine’s war effort. Russia mobilised additional armed forces and fortified their positions in eastern Ukraine in such a way that Ukraine was only able to break through Russian lines sporadically. Russia tried to exploit its numerical superiority; it improved its military strategy and boosted the production of weapons. The failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive was an example of a classic military experience: seizing occupied territory is far harder than holding it.[6]Thus, the warring parties are bogged down in trench wars.

The term "trench wars" is reminiscent of World War One, when destructive battles were fought for many years without much regard for humans and material. However, state-of- the-art technology and sophisticated weapons are also used in this war today. The most obvious illustrations of the new type of warfare are the massive use of drones and high- speed missiles, the importance of military reconnaissance, especially through satellites, and the automation and networking of the battlefield.

The prevailing opinion among Ukraine's supporters is that the country can only gain a good negotiating position through military successes. However, it is doubtful whether more weapons can promote the end of the conflict and a victory for Ukraine. Critically, the German journalist Andreas Zumach said that continued arms deliveries would possibly lead to the war dragging on for years, "with even more deaths, and that in the end many Ukrainian cities would look like Grozny after the second Chechen war.”[7]

The military assessment of the situation oscillates between three different scenarios. First, a military stalemate with a long-lasting, costly war of attrition. Second, ultimately, Russia's dominance, because the country can mobilise more resources than Ukraine, which is already suffering from shortages of ammunition and weapons and is struggling to mobilise enough soldiers. War weariness would lead to Ukraine's defeat. Third, there is a more optimistic scenario, as German Major General Christian Freuding, head of the Ukraine Situation Centre at the Ministry of Defence, recently explained in the Süddeutsche Zeitung:

The Ukrainian armed forces are succeeding. 80 percent of Ukraine is still free, and this after two years against an alleged military superpower. They have regained 50 percent of the territories they had lost. The Black Sea Fleet of the Russians has de facto been pushed out of the western Black Sea. Ukraine is increasingly succeeding in carrying out strikes with self-made weapon systems in depth behind the Russian lines, and is thus achieving considerable effect against command and control facilities and the logistic supply… No one would have believed a few months ago that Ukraine would be able to break Russia's dominance in the Black Sea and resume its steel and grain exports. But this is exactly what has happened because Russian ships are now keeping a great distance from the coast for fear of sea drones or missiles.[8]

But militarily, Ukraine's situation remains tense. Ukraine does not receive enough military supplies and also has difficulties in mobilising enough personnel.

3. Collapse of the European security architecture

The basis of the post-Cold War foreign and security policy in Europe is now eliminated. . One of the cornerstones of the policy of détente ("change through trade") has boomeranged. The thesis from the 1970s that antagonistic systems that are economically close to each other are more inclined to cooperate than to fight military conflicts[9] proved to be a double- edged sword in the case of Russia’s war. European economic dependence on Russia's gas, oil, coal, and other raw materials meant vulnerability and susceptibility to blackmail. The economies in most EU countries had to face painful economic adjustment processes, and the dependencies also set limits to the sanctions against Russia that had been adopted.

The period of détente after the Cold War, initiated with the 1975 Helsinki Act is dead. Arms control is no longer on the agenda. Important nuclear arms control treaties have not been renewed or were terminated and worldwide investments into arms production are booming.

Russia's aggression is an attack on European values. The consequences for the European peace order and the international economic system are immense. If Russia were to gain the upper hand over Ukraine, it would be a blow to democracies in Europe and proof that military aggression pays to achieve nationalist and imperialist goals. A period of further military aggressions might be on the horizon.

Even though the member states of NATO and EU repeatedly stress that direct participation in this war is out of the question, there is already a far-reaching military and economic commitment. Western economic aid, arms deliveries to Ukraine, training of Ukrainian soldiers, and support for military reconnaissance have so far prevented Ukraine's defeat. The deeper this support is, the greater the risk of a direct military confrontation between Russia on the one hand and NATO and the EU on the other.

What political project can end this brutal war and the present stalemate? What could a new European security policy look like? These questions must be raised in view of the huge losses in Ukraine and in Russia and in view of the risks of further escalation.[10]

4. Tough sanctions

Western sanctions against Russia on trade, against individuals and financial restrictions have caused significant effects, but not so much that Russia has been brought to its knees economically. Despite repeated tightening of sanctions, Russia is finding ways to circumvent them. The results of the toughest sanctions ever imposed on a country are mixed.

In sanctions research, it has long been assumed that there are different consequences. In the best case, the behaviour in the target country changes. But there are also usually ways for circumvention and other defence mechanisms. Additionally, it is also important to note that costs may arise in the sending states and in third countries.[11] Thus, sanctions are intended to trigger a change in behaviour in the sanctioned country through coercion. At the same time, they also limit the ability of the sanctioning countries through constraining. These general findings from sanctions research [12] also apply to the sanctions’ regime against Russia. The country was affected by the sanctions, but the weak point remained EU dependence on Russian energy supplies and the reserved reaction in many countries of the Global South.

The US and its allies excluded Russia from the international payment system SWIFT and froze $300 billion in Russian foreign exchange reserves. Around 11,000 banks process international financial transactions through SWIFT which is de facto controlled by the US and its partners. This exclusion of Russia significantly hampered its ability to trade internationally. But already a few weeks after the start of the war, the Russian central bank was able to fend off a collapse of its financial system with capital market controls, so that an economic debacle could be prevented. Although legally not without risks, Western allies of Ukraine try to organise, according to the New York Times, “new support for seizing more than $300 billion in Russian central bank assets stashed in Western nations” to fund Ukraine’s war efforts as financial support is waning.[13]

Export controls have been imposed mainly on high technology: microchips, semiconductors, software, and other dual-use goods that can be used for military and civilian purposes. However, during the course of the war, Russia was able to import some of the sanctioned high technology through third countries.

Russia was largely able to compensate for the drastic reduction in imports of Russian energy supplies by the EU through exports to China and countries of the Global South. An estimated one-third of Russia's state budget comes from oil exports. Even though the Russian economy has been hit hard and many Russian oligarchs can no longer freely access their assets abroad, the impact on the Russian economy has remained limited. A study of the Russia sanctions concludes: “The financial damage to Russia is already considerable, and more than 1,000 companies from all over the world have withdrawn from Russia.”[14] But Russia used this exodus to ensure that Russian investors and the state could buy the production capacities of Western companies at ridiculously low prices. In general, the impact of sanctions should not be overestimated. As a rule, sanctions are more effective in the medium and long term than in the short term.

The aim of sanctions is not only their economic impact, but also to exert political pressure. Sanctioning countries can direct symbolic messages at the target state as well as at the international community. But the history of sanctions has amply shown that dictators and autocrats are able to ward off these pressures. Examples of such extensive and long-term sanctions against Iran and North Korea illustrate that the rulers were able to counter such difficulties through a combination of repressive measures and a "belt-tightening" or “rally- around-the-flag” policy.

5. Solidarity of NATO and EU

Since the beginning of the war, both NATO and EU member countries have assured Ukraine of their full solidarity. It was a clear signal both to Russia and Ukraine. The broad military, economic and political support was not self-evident, especially since NATO was described – not without reasons – by French President Emmanuel Macron in November 2019 as "brain dead".[15] The EU was not a unified power since it was and still is divided on many central issues.

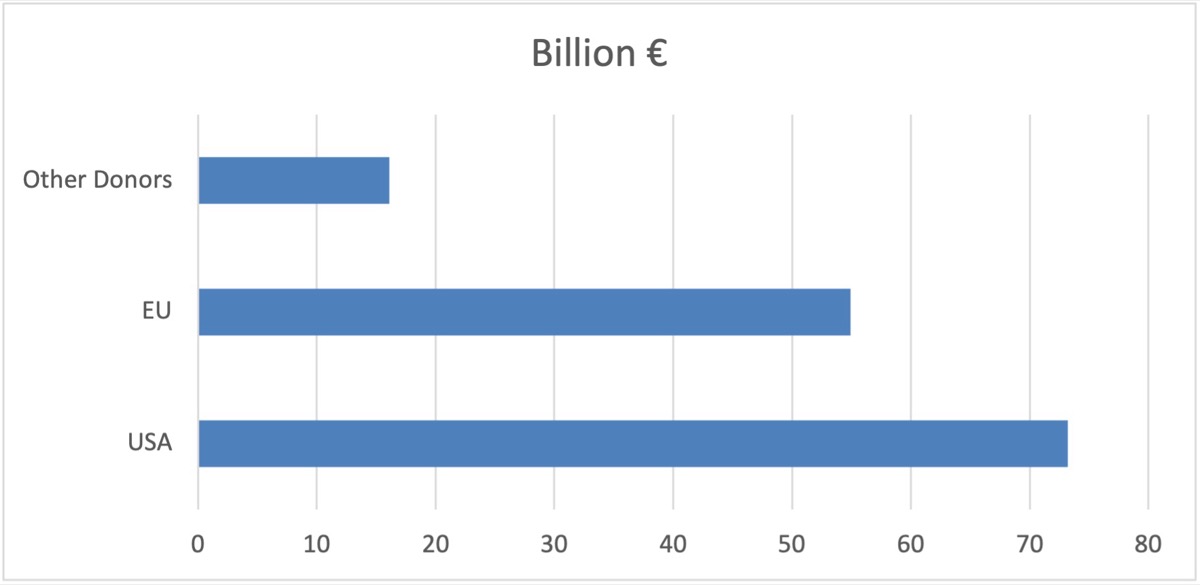

The US is by far the largest bilateral Ukraine donor and committed more aid than the 27 EU countries combined. During the first year of the war, the US pledged the equivalent of €73.18b, the EU €54.92b and other donor countries €16.1b. The EU contribution includes a substantial and unprecedented commitment from the “European Peace Facility” which was originally designed exclusively for development aid. A total of 41 countries participated in aid for Ukraine. These commitments included military, humanitarian, and economic support.

Figure 1: Total bilateral commitments during the first year of war

(24 January 2022 – 15 January 2023)

Source: Kiel Institute for the World Economy[16]

Interestingly, a Ukraine support tracker report concludes after the first year of the war:

Eastern European countries stand out when measuring aid in percent of donor GDP, and even more so if we add the large costs of hosting Ukrainian refugees. In international comparison, it is puzzling why some rich Western European countries, like France, Italy, or Spain provide so little bilateral support. In general EU countries show ongoing hesitancy in providing support to Ukraine… From the outset, military support for Ukraine, particularly the supply of weapons, has been the subject of highly controversial discussions between EU governments and, in some cases, within individual EU countries. The result was a certain hesitancy on the part of the EU, fearing that it would be drawn into this war by antagonising Russia. Practically each decision to supply the different categories of heavy weapons systems (battle tanks, artillery, ground-to-air defence systems, fighter aircraft, high-speed missiles) initiated a new controversy which led to considerable dissatisfaction in Ukraine over the delayed deliveries.

After two years of war, delays in providing military assistance are now less an outcome of political disagreement than of lack of production capacities. According to the New York Times: “Some senior European defense officials quietly acknowledge that the weapons and ammunition that Europe is currently sending to the war can’t match what Ukraine is burning through.”[17] Ukrainiane defence efforts suffer especially from a lack of munitions, air defence systems and repair facilities for damaged weapon systems.

US President Joe Biden said in mid-December 2023 that “Putin is banking on the United States failing to deliver for Ukraine”[18] and the US and Europe losing patience with this war. In the US, support for Ukraine is controversial for domestic political reasons. The EU allocated a new aid package, but it was hotly debated for a long time. Previous promises by EU member states, like the supply of munitions, could not be kept. A certain war-weariness is evident. As was often the case in history, existing conflicts are suppressed in the public consciousness when new events are imminent. The attack of Hamas in October 2023 against Israel and Israel’s reactions in Gaza have somehow side-lined events in Ukraine. Apparently, the promise from the beginning of the war that "we will support for as long as necessary" no longer applies, but instead "as long as we can". The dynamics of aid to Ukraine have certainly slowed down. The above quoted support tracker reports “a new low between August to October 2023 – an almost 90 percent drop compared to the same period in 2022.“[19]

6. Destruction and demoralisation in Ukraine

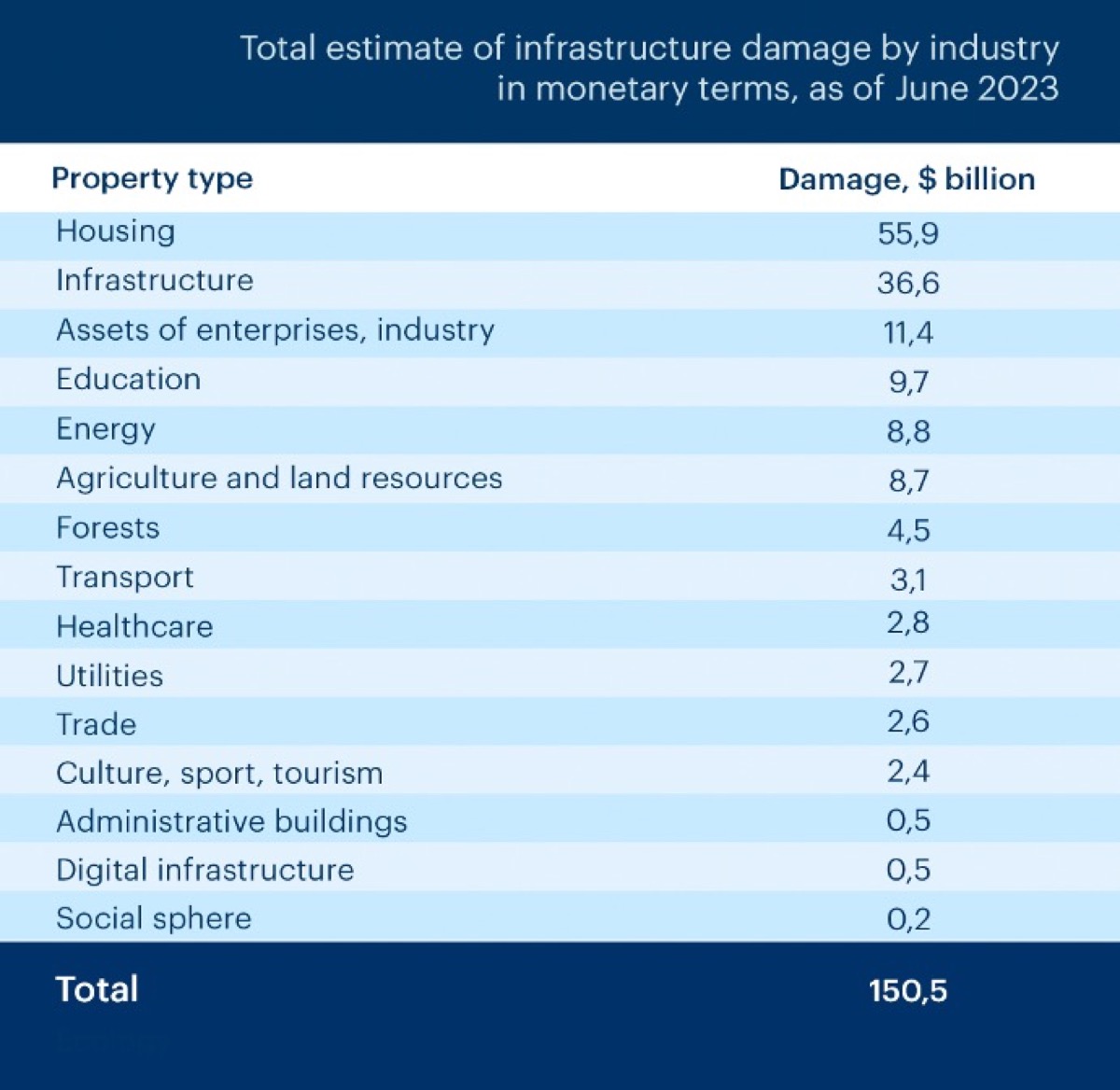

The war has caused severe damage to infrastructure, the industrial base, agriculture, the energy sector, and housing. Ukrainian sources estimated that the damage to the infrastructure amounted to USD $150 billion by June 2023. Many airports, railway stations, administration buildings and educational institutions were destroyed. The Russian strategy of indiscriminate bombings of civilian infrastructure is apparently intended to inflict so much damage to the country that the Ukrainian people will get demoralised. But Russia underestimated at the beginning of the war the determination and courage of the people of Ukraine.

Due to war spending, government spending has risen dramatically, but not government revenues. According to the National Bank of Ukraine, government revenues covered only 43 percent of expenditures between January and August 2023. The dependence on international support and loans on the financial markets is growing.[20] The reluctance in the US and the EU at the end of 2023 to make further aid commitments to Ukraine led to a discussion about the possible confiscation of Russian reserves, which are frozen mainly in the US, to overcome Ukraine's difficult financial situation.

In addition to the material damages, Ukraine is experiencing a demographic crisis since millions of people have fled and tens of thousands have been injured or killed. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated that “17.6 million people in Ukraine are in need of humanitarian assistance, and access for humanitarian assistance to areas affected by the fighting has proved to be challenging.”[21]

Figure 2

Source: Kyiv School of Economics[22]

Before the war, about 41 million people lived in Ukraine. More than 8 million have left the country since the beginning of the war. The United Nations registered 6.3 million refugees, the majority in Europe. After the first year of war more than 1.5 million refugees lived in Poland, over 1 million in Germany and close to half a million in the Czech Republic. The number of Ukrainians internally displaced persons is 7 million. These refugees are mostly women and children. As a result of the war, unemployment rose from just under 10 percent to over 25 percent.[23] In 2023, the situation on the labour market seems to have improved. Nonetheless, besides the traumatisation of thousands of people, the material damage is gigantic. According to a report by the World Bank, the poverty is estimated to have increased from 5.5 percent to 24.1 percent of the population in 2022.[24]

7. Mobilisation of resources in Russia: Towards a war economy

Russia's so-called special military operation poses a double challenge for the economy of the country. The government was forced to mobilise an unexpectedly large range of resources (weapons, ammunition, but also soldiers). In addition, Western sanctions forced the country to readjust its foreign trade and financial system. Contrary to many predictions in the West, Russia has largely succeeded in coping with both challenges, although at a cost. This was possible because Russia managed to change its own export and import chains. Many goods are imported now from other countries and Russian energy exports flushed high revenues into the Russian budget. The drastic increase in arms production boosted the growth of the economy. Contrary to predictions, Russia stabilised the rouble’s exchange rate after a brief slump.

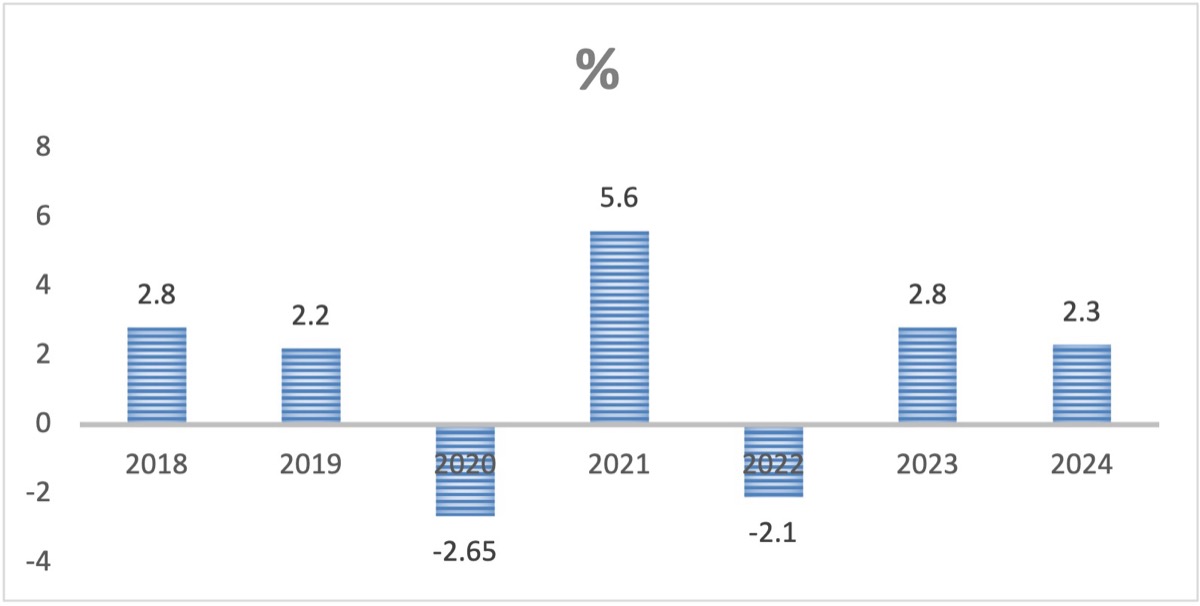

Economic growth was negative in 2019 because of the pandemic and in 2022 as a reaction to the war. However, the 2.1% slowdown in 2022 was significantly less than forecast. In 2023 the gross domestic product (GDP) grew in the third quarter by 5.5% and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects a real GDP growth of 2.2% for 2024.[25] Thus, the transition to a war economy, with high casualties of the Russian military and economic disruptions, did by no means result in a collapse.

Figure 3: Russia’s real GDP growth rate (2018-2024)

(2023 estimate, 2024 forecast)

Source: Statista (2018-2022); Cooper, SIPRI (2023-2024)[26]

Russia did not only lose several tens of thousands of soldiers in the battles but also many weapon systems. Some sources mention as many as 300,000 soldiers killed or badly wounded and some experts assume record losses of combat tanks and infantry fighting vehicles in the high four-digit range.[27]

Since the beginning of the war, Russia was able to mobilise additional personnel, although discontent at home is growing since hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers serve at the front without the prospect of returning home soon. Both the mobilisation of soldiers and the prioritisation of cannons instead of butter have led to labour shortages. The Washington Post estimated that between 500,000 and one million people, many of them highly qualified, left Russia during the first year of war.[28]

The capacity of the Russian defence industry was not designed for a large-scale war. Heavy investments into arms production and supply of weapons and technology from allies (China, Iran, North Korea) facilitated overcoming the initial bottlenecks in provisions of weapons.

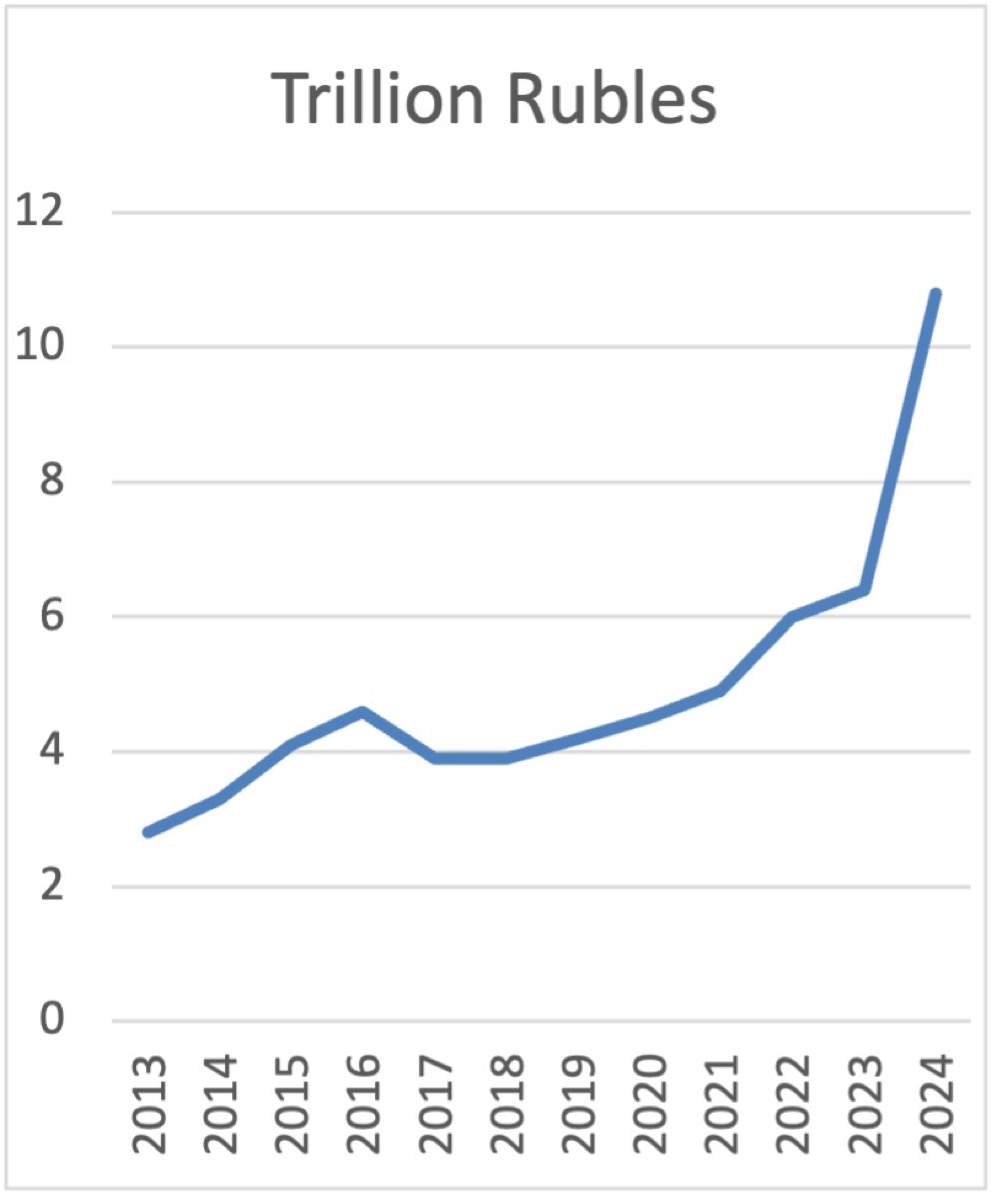

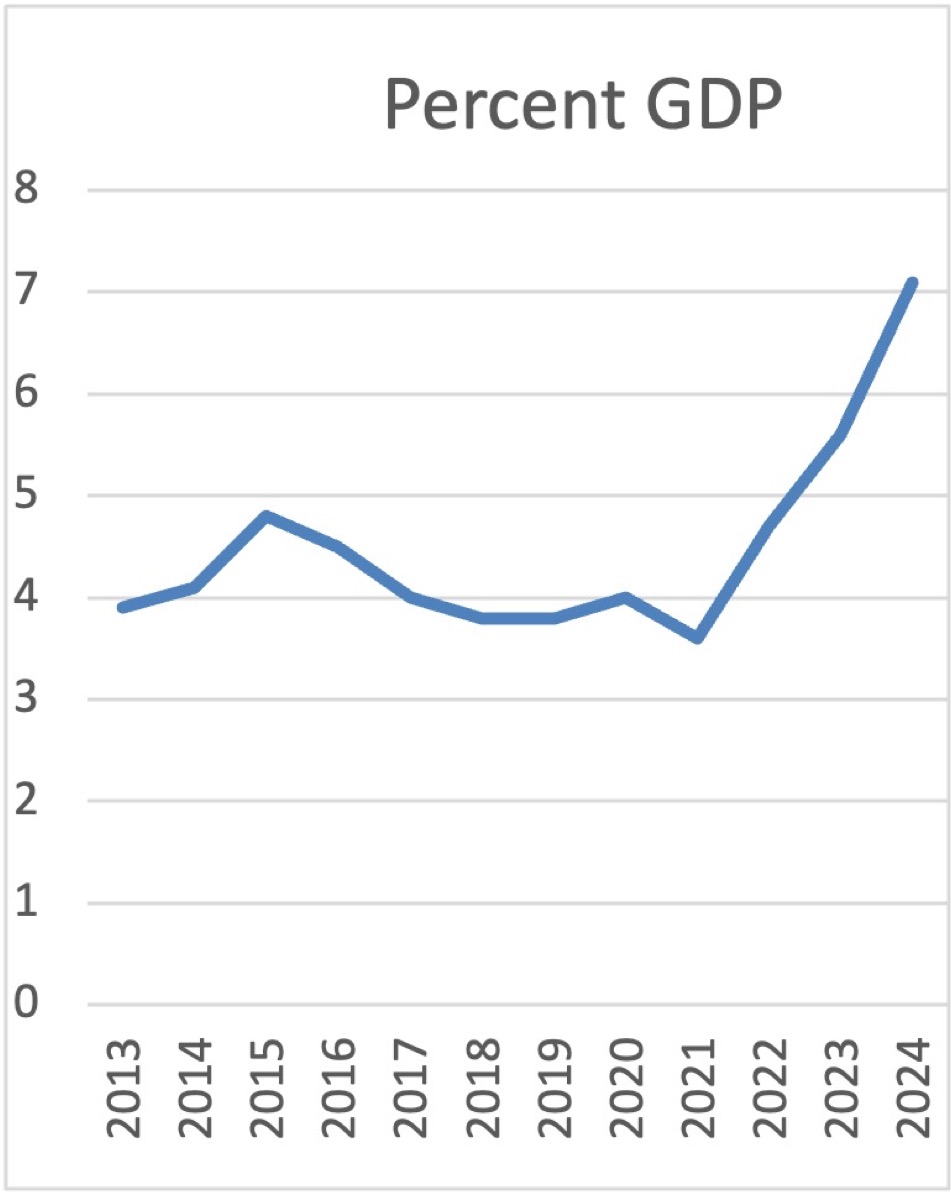

Over the past decade, Russia has spent around 4 percent of GDP annually on the military, amounting to over $71 billion, or 6 trillion roubles in 2022 (see Figure 4).[29] The National defence budget will increase from 6.4 trillion roubles in 2023 to 10.8 trillion roubles in 2024. The combined expenditure for national defence and national security will amount to almost 40 percent of the 2024 national budget.[30]

Figure 4: Russia’s Defence Budget (2013 – 2024)

(draft budget for 2024)

Source: SIPRI[31]

More and more resources are being poured into the war. ”Everything needed for the front”, Russia’s Finance Minister Anton Siluanow declared when he announced an enormous increase of the defence budget. Nearly a third of the roughly $350 billion of the state's budget[32] is spent on armaments ($109 million) and the percentage of military spending in GDP will go up to 7.1 % in 2024.

The war waged on Ukraine has left its mark on Russian society. The prioritisation illustrates that the Russian government does not expect a quick end to the war. Russia's population is forced to tighten their belts.

8. Global impact

The UN General Assembly of March 2, 2022, which "deplores in the strongest terms the aggression against Ukraine"[33] was passed with 141 members voting in favour, 5 against, and 35 abstentions. Despite this unambiguous result and most countries clearly opposed to the war, many are signalling that they are holding back in their criticism of Russia and do not participate in the sanctions.

An unintended consequence of the sanctions imposed on Russia have been serious disruptions of international trade. These disturbances were exacerbated by the fact that interdependencies had arisen because of close trade links. For most governments in the Global South, their own economic interests were more important than supporting the boycott of Russia. Representative of reaction from the Global South is that of the five BRICS members. Only Brazil voted in favour of the UN resolution. Russia voted against, and China, India, and South Africa abstained. In the pronouncements after the BRICS summit in South Africa in August 2023, the Ukraine war was not even mentioned.

The restrained reaction in the Global South came about mainly because of the indirect consequences of the comprehensive sanctions. The sanctions were meant to isolate Russia internationally, but many countries of the Global South suffered disproportionately by drastic price increases for energy, raw materials and grain.

The Chinese government continues to maintain a friendly relationship with Russia but does not forcefully support the Russian "special military operation". But why did Brazil, India, South Africa, and many other countries of the Global South object to the pressure of the Europeans and the US to participate in the sanctions? In June 2022, Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar expressed criticism of Western expectations most clearly by stating “that Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems but the world’s problems are not Europe’s problems.”[34]

Memories of the colonial era, from which some countries still suffer today, come up. Formerly colonised countries reflexively resist any form of (perceived) paternalism. In other words, many countries in the Global South feel pressured to take sides in a war in Europe, while the West's role in many conflicts in the Global South was rather dubious. Many conflicts in the Global South are hardly noticed in the West, while the West is deeply involved in others. Just three days after the start of the war in Ukraine, the Qatari news channel Al Jazeera spoke of the "double standards of the West".[35] The necessity of international norms, which is often presented by Western governments in a paternalistic manner, is all too reminiscent of the relationship between rulers and subordinates from the colonial era.

Commenting on India's position on the Ukraine war, Jaishankar expressed concern about the price of oil. “We are a USD 2,000 per capita economy. The price of oil is breaking our back.”[36] Apparently, Russia’s war against Ukraine has further increased tensions between the Global South and the West – especially with the US as the self-proclaimed leader of the free world. While the dividing lines between authoritarian regimes and liberal democracies seem to be intensifying, many Southern governments pursue a policy of equidistance – i.e. independence from both sides – and multiple alliances, which ties in with the traditional policy of non- alignment. They do not want to be drawn into the systemic conflict between democracies and autocratic regimes. Samir Saran, president of the Indian think tank Observer Research Foundation, argues that the new world order is characterised by self-interest and speaks of "partnerships with limited liability."[37]

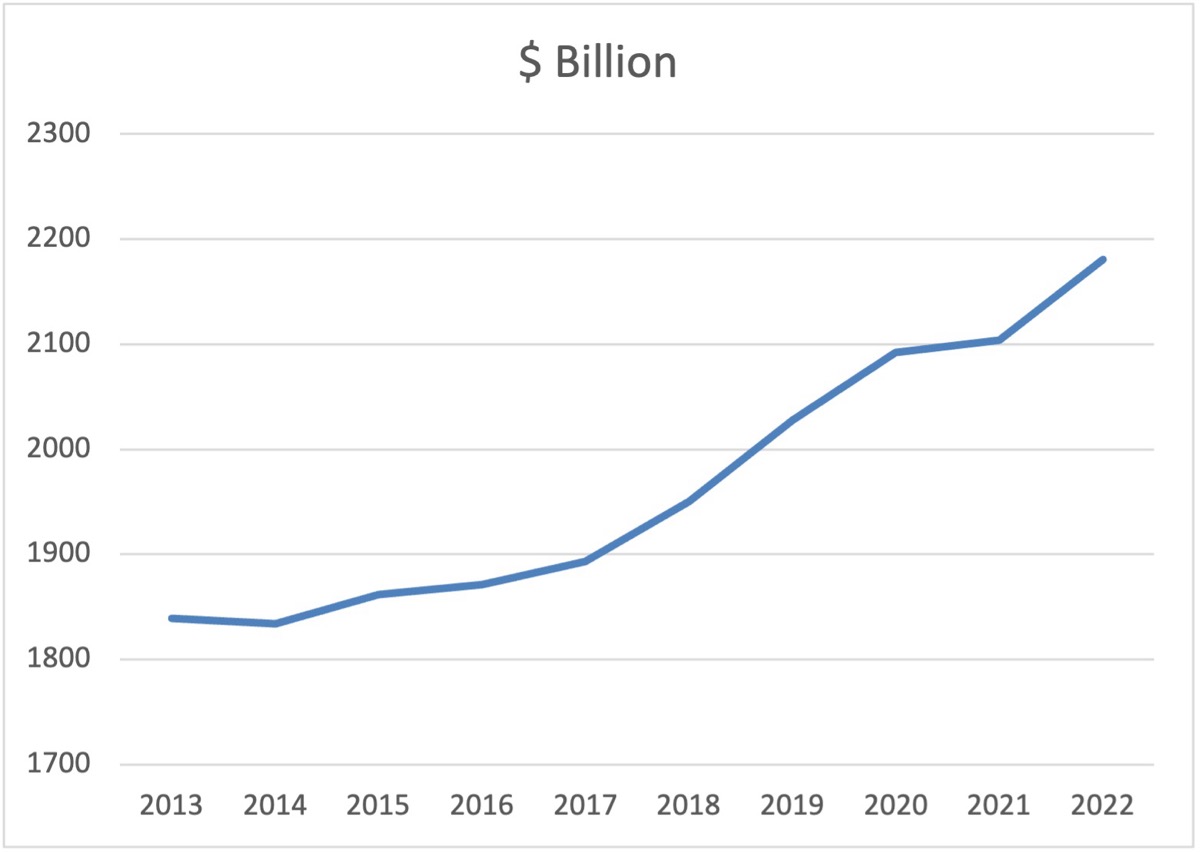

9. Global rearmament

According to SIPRI, world military expenditure rose by 3.7% in real terms in 2022, to reach a record high of $2240 billion. “Global spending grew by 19 per cent over the decade 2013– 22 and has risen every year since 2015.”[38] The invasion of Ukraine and tensions between China and the US and its allies are the main drivers for this dynamic trend in recent years. Tensions in the Middle East and the conflict between Hamas and Israel are also leading to increased investment in the armed forces, not only in the Middle East. Given the decisions and announcements about increased future military spendings in many countries, it can be expected that military expenditures will continue to rise rapidly.

Figure 5: Global Military Expenditure

(Constant 2022 $)

Source: SIPRI[39]

Not only Russian expenditure grew exponentially. “Ukraine’s military spending reached $44.0 billion in 2022. At 640 per cent, this was the highest single-year increase in a country’s military expenditure ever recorded in SIPRI data.”[40] NATO member states had agreed in 2014 to aim at spending of at least 2% of GDP for their armed forces. Although not all NATO countries have reached this threshold, overall spending in NATO amounts to $1100 billion, an average of 2.6% of GDP in 2023.[41] This amounts to half of global military spending. The US spends about two thirds of NATO’s total.

Tensions in Asia also drive the increase in military expenditures. For years, China has been the world’s second largest military spender. The country allocated an estimated $292 billion in its defence budget. This is 63 % more than in 2013. India is also among the top of major military spenders, allocating $81 billion in 2022 for their armed forces. Over the past decade, military spending has grown there by 47%.

The three largest spenders – the US, China, and Russia – account, according to the SIPRI data, for 56% of global military expenditures. Many states are reinforcing their armed forces in the present insecure environment. Apparently, arms control has little chance in these times of multiple conflicts and of significant long-term increases in global military spending as well as expansion of the armaments industry and weapons production.

10 .Side-lined UN

The Russian aggression has been regularly on the agenda of the UN Security Council and the General Assembly since the annexation of Crimea in 2014. But the UN plays a completely subordinate role in this conflict. The UN was not even a major player in the so-called Minsk- process which mediated unsuccessfully in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine in the Donbas region and Crimea between 2014 and 2022. Although it is the most noble task of the Security Council to ensure peace and security in the world, the UN’s hands are tied. The Council is deadlocked as Russia can veto any constructive initiative. In both the General Assembly and the Security Council, delegates urged that intensified efforts be made to bring the warrying parties to the negotiating table and called on Russia to withdraw all its military forces from the territory of Ukraine and for a cessation of hostilities. So far, however, the conditions for negotiations have not been created, neither by the UN nor by other third parties.

Negotiations took place on two issues of this war: the Ukrainian export of grain and other agricultural products, and the exchange of prisoners. In July 2022, under the mediation of UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Turkish President Recep Erdoğan, grain exports from Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea were resumed. The agreement also included supplying the world market with Russian food and fertilizer to stop the global food price spiral and avoid famine. The UN was also represented in a Joint Coordination Centre specially set up in Istanbul to guarantee the safe journey of the ships.[42]

But after a year, an extension of the agreement failed. Russia insisted from the outset that Western sanctions would need to be eased in return, especially for Russia's state-owned agricultural bank, which could not conduct international business. Then, in the fall of 2023, efforts to revive the grain agreement finally failed. The situation has eased somewhat for Ukraine

because it has managed to push Russian warships out of the western part of the Black Sea, although the export of Ukrainian grain is far below its potential level.

The UN did not play a role in the second important issue of negotiations – the exchange of Russian and Ukrainian prisoners of war. These agreements were facilitated by the United Arab Emirates. The two sides have implemented several exchanges, welcomed by the UN chief.[43]

Five Ideas for a Way to End This War

How can the warring parties come to serious negotiations? Can the present deadlock be overcome? The key issues are on the table: a cessation of fighting and an armistice, Ukraine's neutrality or membership in EU and NATO, the future status of Donbass, Luhansk, and Crimea, a political settlement and reliable security guarantees for Ukraine.

History teaches us “that resolutions for even the most vexed conflicts can be arrived at through dialogue.”[44] Most interstate wars ended not because one of the belligerents won but because of negotiations between them. However, as the Swiss conflict mediator and former diplomat Gu nther Ba chler argues: “Experience has shown that parties to a conflict are not prepared to negotiate immediately after the seizure of force. Especially in the case of armed conflicts within and between states, the first shot is preceded by a long phase of tensions, polarizations, threats, and accusations.”[45]

Different positions about a possible end of this war can be identified. Russian President Putin declares that he is prepared to fight until Russia finally wins. Others believe that military victory for Ukraine is possible. A third group hopes for an end to the war through concessions to Russian security interests, as perceived by the Kremlin, especially regarding the Russian occupied territories and an easing of sanctions. Whether or not Ukraine should negotiate with Russia is at the centre of heated discussions. A fourth position considers a military victory by one side to be unlikely.

1. De-escalation, negotiation, mediation

Most security experts including supporters of Ukraine, argue that this war cannot be won militarily and that negotiations are needed to terminate it. Is this war "ripe"[46] now for negotiations? Has the looming war weariness among Ukraine's supporters given rise to the Russian government's hopes of winning this war after all? Or is Ukraine still convinced that it can defeat Russian forces on the Crimea and eastern Ukraine? Presently, continued fighting and a long war of attrition seems more realistic than serious negotiations. Several unsatisfying rounds of talks to end the war with an armistice were held immediately after its beginning in February and March 2022 in Belarus and in Turkey. The Ukrainian government had offered four points as the goal of negotiations, which were rejected by Russia at the time: Ukrainian renunciation of NATO membership, negotiations on the status of Crimea in 15 years, direct negotiations between the two presidents on the Donbass and security guarantees for Ukraine. After the successful defence of the major parts of the territory in summer 2022, the Ukrainian government withdrew from this proposal, pointing out that the Russian government was not seriously interested in a settlement at the negotiation table.

But the desire of Ukraine for the restoration of its sovereignty and full territorial integrity and Russia's goals for the capitulation of Ukraine, or at least the incorporation of the part of Ukraine now occupied into Russia, are irreconcilably opposed. Both hold on to their maximalist positions. It seems negotiations are not on the agenda yet, because Russia has not yet given up on its ambitious goals and Ukraine is motivated to push back the aggressor further.

But surprises are possible. Negotiations usually begin as background discussions, as pre- talks or talks about the possibility of negotiations. Such talks have recently taken place during the Economic Forum in Davos. It is not publicly known to what extent such rapprochements may take place now. The government of Switzerland has offered its good services. According to a report by the New York Times, Russia's president “quietly signals he is open to negotiations about a ceasefire in Ukraine.”[47] The dilemma remains: Is a credible threat needed to make the Russian government consider serious negotiations or will continued massive support to Ukraine lead to further escalation – either that NATO becomes more deeply involved in this conflict, or that Russia could actually use nuclear weapons, as Russian representatives announced several times?[48] In view of the risk of further escalation and the continued suffering on both sides, opportunities for diplomacy should not be ruled out. But after two years of war, no realistic road map for an end has been presented.

The massive rearmament and mutual threats are reminiscent of the Cold War. Although today's situation is significantly different, there are also parallels. The history of de tente shows that, despite miserable conditions, success and numerous arms control treaties were possible in the 1970s and 1980s. The Helsinki Final Act of 1975 laid down important principles. Agreements on national sovereignty, sanctity of borders, respect for human rights and economic, technical, and cultural cooperation were necessary to end the bloc confrontation. Even if the Helsinki principles are now violated by Russia, it is worth looking back to draw conclusions for today.

As long as both sides believe in a military victory, there is little hope for negotiations. But the signs of fatigue that are now clearly noticeable could contribute to pause. No successful diplomatic intervention can be launched against the declared will of warring parties. In their self-perception it seems “more advantageous to both the Russian and Ukrainian leaders to let the weapons do the talking.” Thus, it is important to look for opportunities somewhere between war and peace. “Much would be gained if a ceasefire would be reached in which humanitarian supplies could be improved, demilitarized areas could be negotiated, and thus the killing could be stopped.” [49] In addition, it would be advantageous to put an end to the disruptions to the global economy.

There is a potential role of third parties as mediators if they act impartially and uphold the principles of international law. Governments that have positioned themselves in a neutral position (like India, Brazil, Turkey, Saudi Arabia that initiated a discussion in August 2023) or other bodies like the UN or the churches, might exert their influence to get into serious negotiations. A promising third party could be the G20 Troika, (the past president India, the current president Brazil, and the incoming president South Africa). Even if such attempts, as those by the African Union, have so far been fruitless, it is worth and necessary to keep trying again. Third parties can facilitate overcoming the present deadlock and might enable a face-saving exit from further escalation. Relying only on escalation can lead into the abyss.[50]

None of the third-party interventions might be within short-term reach, but the UN-Turkish brokered grain deal and the UAE facilitated exchange of prisoners of war are proof that humanitarian steps are possible.

2. Institutional opportunities

The traditional negotiation platforms for security in Europe (especially the OSCE) or other channels (like the Minsk process) are in a crisis or have been terminated. Since the Russian attack on Ukraine, these forums have proved to be ineffective and are no longer able to act.

It is worth looking back at the beginning of the policy of détente 50 years ago to possibly deduce from this experience how to get out of today’s impasse. I have argued elsewhere that the history of détente shows that the conditions for its success in the 1970s and 1980s did not seem to be more promising than today. Still, at that time, numerous arms control treaties generated upper limits for weapons, and the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 agreed on a set of important principles, regulating the international relations.

An optimistic vision for future security in Europe could include the following three projects: first, a Helsinki II process, second, a revival of the OSCE, and third, a Minsk follow-up process.

Since Helsinki, the OSCE and Minsk are in extreme difficulties or have been given up, their revival needs to take today’s stumbling blocks into consideration.

Helsinki II: The West's security policy for the 1975 Helsinki Conference consisted of a dual strategy: military strength on the one hand and lasting political relations between NATO and the Warsaw Treaty on the other. Military deterrence with simultaneous negotiations about dismantling of armaments sat alongside political agreements that ultimately led to the resolution of the bloc confrontation.

Although Russia has violated many of the Helsinki principles, in the long term, a Helsinki II process is important. A European security architecture must take Russia into account. A political project must be pursued in which nuclear deterrence is contained, i.e., a return to predictability, a significant reduction, not necessarily a complete decoupling of economies, the opening of arms control negotiations as well as peace negotiation about Russia’s war in Ukraine. Perhaps this will lead to de-escalation, confidence-building, arms control and disarmament. The 50th anniversary of the Helsinki Final Act in 2025 would be a symbolic occasion for a new start.

Revival of the OSCE: The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, with its 57 member countries in Europe, North America, and Central Asia, offers a forum for dialogue on security conflicts. But the existing confrontation has led to a marginalisation of the organisation, which is in dire need of revival in the face of the Ukraine war and other "frozen" conflicts (for example in the Caucasus). The OSCE is a consensus-based organisation and substantive decisions are consistently prevented by Russia. Ukraine's supporters in the EU and NATO refuse to cooperate with Russia because it could be seen as a concession to Russia. During the December 2023 ministerial meeting in Skopje, North Macedonia, the complete breakdown of the organisation was prevented. But since Russia’s foreign minister Sergej Lavrov was invited, Poland, the Baltic countries and Ukraine refused to participate. There is no way around talking to each other if the assumption is correct that the war in Ukraine cannot be won by either side. It is essential not to destroy dialogue forums, which will definitely be needed in the future.

Minsk follow-up: In the Minsk I and Minsk II agreements, measures were agreed to politically settle the war in eastern Ukraine, which has been waged since 2014. Russia, Ukraine and the OSCE, with the mediation by leaders of France and Germany (the so-called Normandy Format) agreed on several measures, including a ceasefire, withdrawal of weapons, release of prisoners of war and political arrangements for the Donbas region. But the agreement was never fully implemented and, with the beginning of the war in February 2022, Russia’s president declared the agreement invalid. Understandably Ukraine has rejected negotiations along the lines of the Minsk agreements, and President Putin declared the agreement a failure before Russia's attack on Ukraine.

To end the fighting and to relocate weapons at the border, an OSCE-like or Minsk-like format is needed. However, in contrast to the past Minsk agreement, a clearly defined ceasefire line is needed, monitored by a third party equipped to carry out surveillance, for example in the form of a robust UN peacekeeping mission. [51] Furthermore, it is important to guarantee Ukraine’s security. Such guaranties could be granted by the US in combination with other countries, as former NATO-Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen and Andrii Yermak, Head of the Ukraine Presidential Office, suggested already in September 2022.[52] In addition to the primarily military issues, reparations, and support for the reconstruction of Ukraine would have to be dealt with in this format.

Whether these forums are called “Helsinki”, “OSCE” or “Minsk” is not relevant. “Such forums are still necessary today, despite, or perhaps because of, the deadlocked confrontation. Not only to end the war in Ukraine, but also to stop and de-escalate the uncontrolled arms race at all levels in the longer term. Regardless of the course of the Ukraine war, serious negotiations will be necessary at some point. A ceasefire or even peace is hardly possible without negotiations, and war is never an answer to anything.”[53]

3. Reconstruction of Ukraine

Although the war still goes on, the reconstruction of Ukraine has begun. However, the prerequisite for sustainable reconstruction of the country is that the war damages are repaired and, above all, that this process is not torpedoed by constantly renewed destruction. Therefore, in addition to military support, political and economic support is also needed. The EU Commission proudly announced: “The EU is committed to playing a major role in Ukraine’s recovery, reconstruction and modernisation, supporting investments needed to rebuild the country and ensure a smooth transition towards a green, digital, and inclusive economy.”[54] They agreed on a Ukraine-facility, a four-year (2024- 2027), €50 billion fund for non-repayable and loan support to “cater for both short-term recovery needs and medium-term reconstruction and modernization of Ukraine”.[55]

In December 2023, the European Council (the heads of state and governments of the 27 EU members) decided that EU accession negotiations with Ukraine can begin. In doing so, the EU and Ukraine are building on the reform process that began in 2014, which primarily includes the decentralisation of administration, judicial and constitutional reform, and anti- corruption reform.[56] However, EU accession negotiations with other countries show that this process usually take many years.

Of the approximately $74 billion aid provided by the US between January 2022 and October 2023, 35% ($26.4 trillion) is economic assistance, and 4% ($2.7 trillion) is humanitarian assistance.[57]

Compared to other reconstruction programmes of the past, these are enormously large sums. But, given all the commitments about solidarity with Ukraine, further aid looked uncertain at the end of 2023 and the beginning of 2024.

The idea of this reconstruction is to provide the country with an economic future. But huge challenges lie ahead: the removal of debris, reconstruction of infrastructure (road, rail, utility networks), skilled labour shortages, etc. It is not only government support measures that are important, but also private investment and technical know-how. Millions of people in Ukraine are traumatised: soldiers on the frontline, refugees inside and outside Ukraine and, above all, children – a daunting task to cope with.

4. UN Trusteeship

Membership in both the EU and NATO seems to be Ukraine's top priority now. However, to enable long-term peace, other solutions should not be ruled out from the outset. Already a year ago, experts proposed the possibility of a demilitarised zone under the auspices of the United Nations. The goal should be a ceasefire and the Security Council should mandate a UN peacekeeping force. Ukraine could remain neutral and as a next step could a more comprehensive peace order in Europe be negotiated.[58]

Fischer considers it desirable "that NATO and the EU member states, instead of constantly expanding their military arsenals, strive for a policy of demilitarization under the auspices of the United Nations." [59] A temporary UN mandate could be an alternative to the present deadlock, especially if it is combined with security guarantees for Ukraine. The main responsibility of the UN would be to provide security, enable reconstruction and to re- establish public institutions. Of course, critics argue that only with the basis of a trustworthy and forceful defence posture by Ukraine and its supporters would President Putin consider negotiations. A complicating factor is that Russia codified the incorporation of four of the occupied Ukrainian regions in its constitution.

5. Global reforms

The Ukraine conflict has exposed the geopolitical fault lines. It is not just about the collapse of the European peace architecture. The globally over-arching rivalry between the US and China is now also seen as a conflict over a liberal, democratic as opposed to an authoritarian world order. At least three aspects of global relations are important as a result of this war : the challenge to the Western-dominated global economic order, the danger of escalation into a larger war, and the largely unchecked rearmament and the lack of arms control forums.

The rivalry and competition for spheres of interest and influence is both underlined by China’s assertive foreign policy, backed up by a dynamic modernisation of its armed forces as well as by the US global policy. The US National Security Strategy of 2022 clearly states that the Biden Administration wants “to position the United States to outmanoeuvre our geopolitical competitors.” [60] Already during the presidency of Donald Trump, the US pursued a policy of extensive decoupling from China. The EU, following a somewhat more moderate course, sticks to the formula that has been propagated for several years: China is both a partner, a competitor but also a systemic rival.[61] Therefore, de-risking but not de- coupling would be needed.[62] Whether this is more than a shift in terminology will be proven during the next few years in the development of international trade relations.

The war in Ukraine has clearly exposed the economic differences between the US and the EU on the one hand and the Global South on the other. NATO’s and the EU’s push for isolating Russia internationally has shown both the collision of economic interests as well as the ideological divide between China and Russia versus the US and allies. The Western liberal narrative of democracy and human rights, of a rules-based world order, will meet with interest and approval only if the legitimate wishes of the Global South are considered and if a reliable multilateral system of equal states develops. So far, the West has been far too hesitant to respond to the needs of the Global South and is still sticking to its Western- dominated world order.

For the West, a difficult balancing act lies ahead: the need to reach out to the Global South and take its legitimate wishes seriously and, at the same time, to uphold its own norms and values. It is necessary to insist that responsibility for this war lies in Moscow. Therefore, it is in the interest of the West, particularly Europe, to continue to consistently practice solidarity with Ukraine against Russia's aggression.

But Ukraine, and including Western security policy, faces a dilemma. Effective defence against Russian aggression is still needed, both through military action, through the maintenance of sanctions and through economic support for Ukraine. At the same time NATO is close to direct involvement in this war, with the risk of further escalation. For this reason, it is also necessary to signal a willingness to talk, even if Russia is reluctant to enter negotiations now. It is in Europe’s own interest to maintain a sufficiently stable coexistence with Russia, which relies on defence but also strives to achieve a minimum arms control.

In the short term, there will probably be no agreement with Russia on the territories annexed in violation of international law in eastern Ukraine and Crimea. This means that these conflicts may be "frozen" for a long time, as is already the case in various places in the post-Soviet space (Abkhazia, South Ossetia Transnistria). This may seem unsatisfactory and unjust in the face of Russia’s violation of international law. However, it would enable Ukraine to recover economically and spare human lives. It would be fatal to give up hope for a lasting security and peace order.

The prolongation of the present policy is not only problematic because further escalation could end in disaster. In view of the problems of the world (climate crisis, poverty and inequality), we cannot afford to waste scarce resources in this unprecedented arms race. All energy, ambitions and finances should be focused on the central global challenges.

NOTES

[1] The war started in 2014 with the invasion of Crimean, leaving aside the hybrid war in the East.

[2] United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, 19. October 2023, Report A/78/40, p. 2, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/coiukraine/A-78-540-En.pdf.

[3] Ibid, p. 5.

[4] Ibid, p.2.

[5] Ibid, p.4.

[6] Jones, Seth G., Riley McCabe and Alexander Palmer (2023),Seizing the Initiative in Ukraine, in: Center for Stra- tegic & International Studies, CSIS Briefs, October, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-10/231012_Jones_Initiative_Ukraine.pdf?VersionId=fLXQB2rZKhqVNiq8xRTeywAE7a3_C3xG

[7] In: The German TV channel Phoenix-Runde, 10. January.2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CI4WpWFOfIA&t=914s.

[8] Christian Freuding, in Su ddeutsche Zeitung, 28 December 2023.

[9] Keohane, Robert O. and Joseph F. Nye (1977), Power and Interdependence, Springer, Boston.

[10] Wulf, Herbert (2022): Escalation, De-escalation and Perhaps–Eventually–an End to the War?, in: Toda Policy Brief 128, April, https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-128_escalation-and-de-escalation_wulf.pdf.

[11] Doxey, Margeret (1980) Economic Sanctions and International Enforcement, MacMillan Press, Basingstoke and London.

[12] An overview of the effects of sanctions in: Peksen, Dursun (2019), When Do Imposed Economic Sanctions Work? A Critical Review of the Sanctions Effectiveness Literature, in: Defence and Peace Economics 30, No. 6, pp. 635–47. Hufbauer, Gary Clyde et al. (2007), Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, 3rd edition (Washington, DC: Peterson Insti- tute of International Economics).

[13] New York Times, 21 December 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/21/us/politics/russian-assets-ukraine.html#:~:text=The%20Biden%20administration%20is%20quietly,is%20waning%2C%20according%20to%20senior.

[14] Soest, Christian von (2023), Russland: Was ko nnen Sanktionen bewirken? In: Bundeszentrale fu r Politische Bildung, Bonn, https://www.bpb.de/themen/europa/russland/514169/russland-was-koennen-die-eu-sanktionen-bewirken/.

[15] Emmanuel Macron in an interview with the Economist, 7. Nov. 2019, https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/11/07/emmanuel-macron-warns-europe-nato-is-becoming-brain-dead#.

[16] Kiel Institute for the World Economy (2023), The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which Countries help Ukraine and how?, Kiel Working Paper 2218, February, p. 51. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/the-ukraine-support-tracker-which-countries-help-ukraine-and-how-20852/.

[17] New York Times, 13 December 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/13/briefing/ukraine-war-russia-biden.html

[18] Ibid.

[19] Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Ukraine Support Tracker https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/news/ukraine-support-tracker-new-aid-drops-to-lowest-level-since-january-2022/

[20] Quoted in: Slaviak, Natalia (2023), The Ukrainian Economy and its Destruction, in: Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn. https://www.bpb.de/themen/wirtschaft/europa-wirtschaft/543057/die-ukrainische- wirtschaft-und-ihre-zerstoerung/.

[21] United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, ibid.

[22] Kyiv School of Economics, https://kse.ua/about-the-school/news/the-total-amount-of-direct-damage-to-ukraine-s-infrastructure-caused-due-to-the-war-as-of-june-2023-exceeded-150-billion/.

[23] Slaviak, Natalia (2023), The Ukrainian Economy and its Destruction, in: Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn. https://www.bpb.de/themen/wirtschaft/europa-wirtschaft/543057/die-ukrainische-wirtschaft-und- ihre-zerstoerung/.

[24] World Bank, Ukraine, Macro Poverty Outlook 10/202, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/d5f32ef28464d01f195827b7e020a3e8-0500022021/related/mpo-ukr.pdf.

[25] IMF, https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/RUS.

[26] Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/263621/gross-domestic-product-gdp-growth-rate-in-russia/. Cooper, Julian (2023), Another Budget for a Country at War, SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security, No. 2023/11, December, https://www.sipri.org/publications/2023/sipri-insights-peace-and-security/another-budget-country-war-military-expenditure-russias-federal-budget-2024-and-beyond.

[27] Freuding, ibid.

[28] Ebel, Fancesca and Mary Ilyushina, Russians Abandon Wartime Russia in Historic Exodus, 13 February 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/02/13/russia-diaspora-war-ukraine.

[29] https://milex.sipri.org/sipri.

[30] Cooper, SIPRI, ibid. p. 8.

[31] https://milex.sipri.org/sipri and Cooper, ibid.

[32] https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/90753.

[33] UN General Assembly, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/293/36/PDF/N2229336.pdf?OpenElement.

[34] Indian Express, 4 June 2022, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/europe-has-to-grow-out-of-mindset-that-its-problems-are-worlds-problems-jaishankar-7951895/.

[35] Al Jazeera, 27. February 2022, Externer Link: www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/27/western-media-coverage-ukraine-russia-invasion-criticism.

[36] The Telegraph Online, 27. September 2022 https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/we-are-a-usd-2000-per-capita-economy-the-price-of-oil-is-breaking-our-back-says-s-jaishankar/cid/1889086.

[37] The Indian Express, 23 May 2023, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/the-new-world-shaped-by-self-interest-8623581/.

[38] SIPRI, https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2023/world-military-expenditure-reaches-new-record-high-european-spending-surges

[39] SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, https://milex.sipri.org/sipri.

[40] Ibid.

[41] NATO official figures based on 2015 prices and exchange rates, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2023/7/pdf/230707-def-exp-2023-en.pdf.

[42] https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative

[43] https://www.aa.com.tr/en/russia-ukraine-war/un-chief-welcomes-major-russia-ukraine-prisoner-ex-change/3100605.

[44] Bisaria, Ajay and Ankita Dutta (2023), The Ukraine Conflict: Pathways to Peace, Observer Research Founda- tion, Special Report, No 207, New Delhi, p. 7, https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ORF_SpecialReport-207_Ukraine-Pathways-to-Peace.pdf.

[45] Ba chler, Gu nther, in Neue Zu rcher Zeitung, 7 March 2023, https://www.nzz.ch/meinung/verhandlungen-im-ukraine-krieg-sind-nur-im-europaeisch-globalen-rahmen-moeglich-ld.1728054.

[46] The term „ripeness for negotiations“ is used by Zartman, I. William (1989), Ripe for Resolution: Conflict and Intervention in Africa. New York: Oxford University Press.

[47] New York Times, 23 December 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/23/world/europe/putin-russia-ukraine-war-cease-fire.html#:~:text=Mr.%20Putin%20has%20been%20signaling,and%20interna-tional%20officials%20who%20have.

[48] Charap, Samuel and Miranda Priebe (2023), Avoiding a long War. U.S. Policy and the Trajectory of the Russia- Ukraine Conflict, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PEA2500/PEA2510-1/RAND_PEA2510-1.pdf.

[49] In a thorough analysis, peace and conflict researcher Martina Fischer has shed light on the possibilities for ending the war. Fischer, Martina (2023), Wie ist dieser Krieg zu deeskalieren und zu beenden?, in: Bundeszentrale fu r Politische Bildung, https://www.bpb.de/themen/deutschlandarchiv/523377/wie-ist-dieser-krieg-zu-deeskalieren-und-zu-beenden-teil-1/#footnote-target-28.

[50] Wulf, Herbert (2022), Escalation, De-escalation and Perhaps – Eventually – an end to the War?, Toda Policy Brief No. 128, April, https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-128_escalation-and-de-escalation_wulf.pdf.

[51] Fischer, Ibid.

[52] Rasmussen, Anders Fogh and Andrii Yermak (2022), The Kyiv security compact – International security guaran- tees for Ukraine: recommendations, September Kyiv, https://www.president.gov.ua/storage/j-files-storage/01/15/89/41fd0ec2d72259a561313370cee1be6e_1663050954.pdf.

[53] Wulf, Ibid., p. 7.

[54] https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/factsheet-new-ukraine-facility-recovery-reconstruction-modernisation-ukraine_en.

[55] https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/ukraine-facility-eus-chance-take-leadership-ukraines-economic-re-covery

[56] Pryhornytska, Nataliya (2023), A modern, sustainable and inclusive reconstruction, in: Bundeszentrale u r Politische Bildung, Bonn, https://www.bpb.de/themen/wirtschaft/europa-wirtschaft/543138/debatte-wie-die-ukraine-wiederaufbauen/.

[57] Kiel Institute for the World Economy (2023), ibid.

[58] Kanninen, Tapio and Heikki Patoma ki, Friedenspla ne, Le Monde diplomatique (German edition, January 2023, https://monde-diplomatique.de/artikel/!5906061.

[59] Fischer (2023), Ibid.

[60] White House (2022), National Security Strategy, October, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/8-November-Combined-PDF-for-Upload.pdf.

[61] https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_meaning_of_systemic_rivalry_europe_and_china_beyond_the_pandemic/.

[62] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_2063.

The Author

Herbert Wulf is a Professor of International Relations and former Director of the Bonn International Center for Conflict Studies (BICC). He is presently a Senior Fellow at BICC, an Adjunct Senior Researcher at the Institute for Development and Peace, University of Duisburg/Essen, Germany, and a Research Affiliate at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago, New Zealand. He serves on the Scientific Council of SIPRI.

Toda Peace Institute

The Toda Peace Institute is an independent, nonpartisan institute committed to advancing a more just and peaceful world through policy-oriented peace research and practice. The Institute commissions evidence-based research, convenes multi-track and multi-disciplinary problem-solving workshops and seminars, and promotes dialogue across ethnic, cultural, religious and political divides. It catalyses practical, policy-oriented conversations between theoretical experts, practitioners, policymakers and civil society leaders in order to discern innovative and creative solutions to the major problems confronting the world in the twenty-first century (see www.toda.org for more information).

Contact Us

Toda Peace Institute

Samon Eleven Bldg. 5thFloor

3-1 Samon-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0017, Japan

Email: contact@toda.org