Peace and Security in Northeast Asia By Hugh Miall | 11 July, 2024

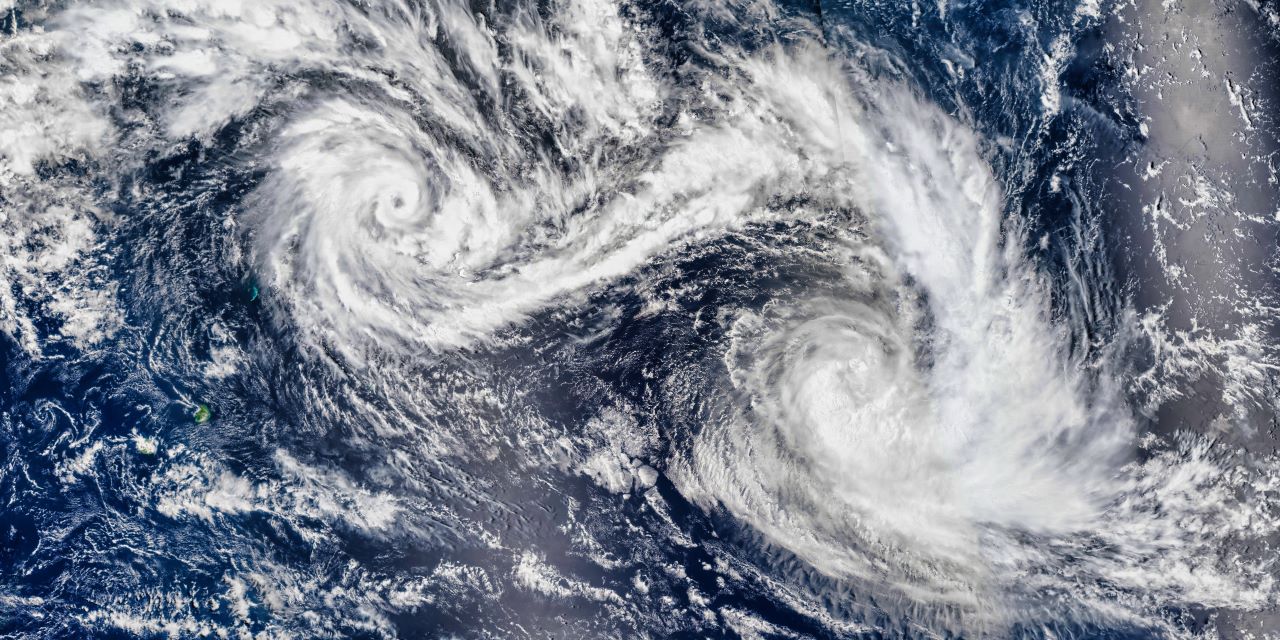

Turbulent Currents, Merging Storms: Northeast Asia Outlook June-July 2024

Image: BEST BACKGROUNDS/shutterstock.com

When two nearby cyclones rotate around each other, merging into a larger and more dangerous storm, meteorologists call it the Fujiwhara effect.

Is something like this developing in Northeast Asia?

Recent decades have seen an increase in what analysts call ‘transnational conflicts’ – that is, conflicts with local, regional and international dimensions. Ukraine is one example, Taiwan is another. It is difficult to address these multi-level conflicts, since responses are needed at all three levels.

Recently, transnational conflicts in different parts of the world have started to merge together. Responding to these emergent global conflict complexes will be a still more daunting challenge.

East Asia has a raft of unresolved conflicts, left over from the postwar settlement of 1945. The legacy of the Korean war fuels continuing tensions and fears of war. The unresolved dispute over the status of Taiwan leads to dangerous military activity around the island. The territorial and maritime disputes in the East and South China Seas involve clashing nationalisms but also broader strategic concerns over supply lines and resources. Events in these hotspots were always calibrated against the state of relations between the US and China, China and Japan, Japan and North Korea. But it is only recently that they have become connected with conflicts in Europe.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 rang warning bells in policy circles in East Asia. Policy-makers feared that President Xi might be emboldened to act against Taiwan following Putin’s lead. The Ukraine conflict came closer with North Korea’s decision to supply the Russian Federation with weapons, and closer still when President Putin concluded a defence pact with Kim Jong-Un in June 2024. The Russian Federation and North Korea pledged to provide mutual assistance should either be attacked. Kim Jong Un offered “full support and solidarity to the Russian government, army and people in carrying out the special military operation in Ukraine” (CBS News, 19 June 2024). Meanwhile, on the Korean peninsula, Kim Jong Un warned his people to prepare for war, and ordered the army to undertake ‘actual war drills’, while proposing to change the constitution to refer to ‘completely occupying, subjugating and reclaiming the R.O.K. and annexing it as a part of the territory of our republic in case a war breaks out on the Korean Peninsula.’

At the same time, the West has not yet learned the lesson that NATO expansion is dangerous, and NATO is preparing to expand its activities into the Indo-Pacific region and north east Asia. NATO is developing links with South Korea and Japan and invited them to attend its last two summits.

Staff talks between NATO and the Japanese Self Defence Force have identified areas of cooperation in responding to security challenges, cybersecurity and military planning. A NATO office was to have been opened in Tokyo, though France objected to this plan. NATO sees its involvement in the area as a necessary response to the challenges to the ‘rules-based order’ coming from China, North Korea and Russia. The NATO summit of July 2023 declared that “The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values.’ The NATO Secretary General followed this up by saying that security is now globalised and security crises in one part of the world reverberate in another.

In April, before attending the NATO Summit for the first time as a South Korean leader, President Yoon condemned any ‘attempt to change the status quo by force’ in the Taiwan Strait, and promised that South Korea would cooperate with the international community to prevent such an outcome. The Japanese strategic community also believes that Japan would be drawn in, under this contingency. The Korean and Taiwan and Japan-China conflicts are thus potentially interlinked.

China and North Korea see the collaboration between NATO and Japan and Korea as a US-led effort to bring NATO into the region. In North Korea’s case, it is seen as part of a US strategy to overthrow Kim’s regime. In China’s case, NATO expansion is seen as a "grave challenge" to global peace and stability. "Despite all the chaos and conflict already inflicted, NATO is spreading its tentacles to the Asia-Pacific region with an express aim of containing China."

The US is deliberately emphasising the interconnections between the European and Indo-Pacific theatres as part of its strategy of building alliances with democratic partners. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan noted:

"We are also growing the connective tissue between US alliances in the Indo-Pacific and in Europe…allies in the Indo- Pacific are staunch supporters of Ukraine, while allies in Europe are helping the United States support peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait."

NATO has addressed the possibility that it might become involved in conflict in the Taiwan Strait, specifically in the situation where US territory and forces came under attack, which would trigger Article 5.

China also objects to the participation of NATO members’ naval units in Freedom of Navigation operations in the Taiwan Straits.

How can the risks of transnational conflicts coming together into global conflict complexes be defused? Second-track dialogue meetings can convene interlocutors from different arenas and bring them together to discuss all aspects of a situation. But though dialogue efforts are vital, they cannot bear the weight of conflict prevention alone. Restraint, trust-building and moderation on the part of political leaders is also needed. So is a climate of domestic political discussion that replaces security fears and nationalism with mutual understanding and an appreciation of our common humanity.

Related articles:

Floating in uncertain waters: Northeast Asian outlook January - March 2024 (3-minute read)

South Korea-China cooperation still has a long way to go (3-minute read)

Understanding China: Myths and realities (10-minute read)

Hugh Miall is Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the University of Kent, and Chair of the Conflict Research Society, the main professional association for peace and conflict researchers in the UK. He has been Director of the Conflict Analysis Research Centre and Head of the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent and a Research Fellow in the European Programme at Chatham House. He is a Senior Research Fellow at the Toda Peace Institute.