Climate Change and Conflict By Robert Mizo | 13 July, 2023

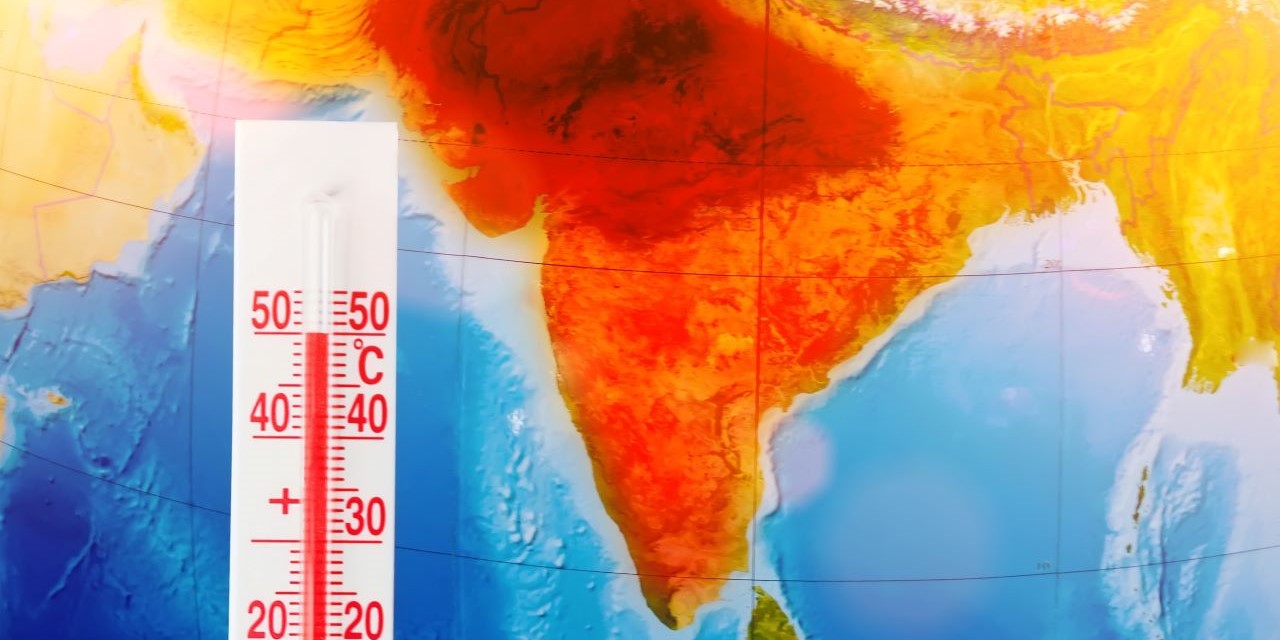

Riding the Heatwave: India’s Sweltering Exposure to Climate Change

Image: aappp/shutterstock.com

The end of June brought monsoon rains to North India as it always does. The rains were a welcome respite from the scorching heat the region reeled under since March. The heat waves that swept through North India in 2023 made headlines across the world as they killed dozens and many at-risk in the population sought medical assistance. The rain also caused floods in parts of the country such as the North-eastern state of Assam. Between heatwaves and floods, India’s western coast witnessed Cyclone Biparjoy making landfall in June, uprooting trees, crops, electric poles and human lives in its wake. These extreme climatic events attest to the fact that India is witnessing and enduring the impacts of climate change.

North India is naturally hot and humid in the summer months of April to August during which it experiences Loo conditions followed by high humidity. However, 2023 saw heatwaves arriving earlier than usual―by 3 March―in Northern India. More than 60 per cent of the country recorded temperatures higher than usual as per India’s Meteorological Department’s (IMD) report. The IMD also reported that by 3 April, 11 states and Union Territories in India experienced heatwave conditions. In India, a region is declared to be facing heatwaves based on the maximum temperatures it records – at least 40⁰C in the plains, 37⁰C in coastal areas and 30⁰C in hilly regions. The departure from normal temperatures should be at least 4.5 degrees. In parts of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Delhi, temperatures touched 47⁰C during the months of March to May 2023. While North India has a history of heatwaves, what is unique and worrying now is the early onset of the heat spells and their prolonged nature.

Heatwaves kill people. Between 2003 and 2022, approximately 10,000 people have died in India due to exposure to heatwaves, according to IMD records. The IMD also reports that there has been a rise of 34 per cent in deaths due to heat waves between 2003-2012 and 2013-2022. It is highly likely that these numbers under represent the actual counts. In 2023 alone, hundreds of deaths due to heatwaves have been reported from several regions in the country. As of 19 June, at least 68 people reportedly died in Ballia district in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, while its neighbouring state Bihar reported 45 deaths. In April, the state of Maharashtra also reported the deaths of around a dozen people from heatstroke while many were hospitalised for heat-related stress. Reporting heatwave-related deaths becomes politically charged, causing rows in some cases. For instance, the medical officer in Ballia, Uttar Pradesh, who declared the deaths as heat-related was reprimanded and transferred, probably in a bid to save face by the state authorities. Like other effects of climate change, it is society’s most vulnerable population with poor housing and working conditions who are most effected by heatwaves.

Apart from the rising human casualties, heatwaves have other indirect and non-human impacts. Even when heatwaves do not cause health issues or death, they have a bearing on the day-to-day functioning of people, especially those in lower income brackets. Daily wage labourers and agricultural farmers face enormous risks working under heatwave conditions, impacting their productivity and ability to work. A study by Lancet reported that exposure to heat caused a loss of 167.2 billion potential labour hours among Indians in 2021 alone. Further, heat puts a strain on existing infrastructure. Many schools in rural India have tin roofed structures, which become heat containers during heat spells, where very little learning can take place. The impact of heatwaves is also gendered, it has been found. Women in poorer sections of India are faced with reduced productivity causing lowered incomes, which further heightens their socio-economic vulnerability. Being out of work, most women face the challenge of being trapped in dangerous indoor heat due to cramped living conditions. Further, one study of households across India, Pakistan and Nepal linked a 1⁰C rise in the yearly average temperature to a 4.5 per cent increase in intimate partner violence (IPV).

The agriculture sector is exposed to extreme stress during heatwaves with heightened demand for water for irrigation causing a strain on already scarce water resources. Heatwaves are also known to reduce crop yields, increase incidence of pest and diseases, and cause soil degradation. India’s heavy dependence on agriculture for employment and food security makes it especially vulnerable to heatwaves. Demands for cooling have caused failure of electricity grids, causing huge losses to productivity and mass discomfort.

Heatwaves are expected to be a recurring phenomenon in India’s future climate. There are varying estimates about its severity, though. A recent study by the University of Cambridge projected that more than 90 per cent of the country is vulnerable to heatwaves and will suffer loss of livelihood, reduction of crops yield, rise in vector-borne diseases and challenges to urban sustainability. However, India’s National Climate Vulnerability Index (CVI), developed by the Department of Science and Technology, estimates merely 20 per cent of the country is vulnerable to climate impacts. This underestimation is a result of a methodological problem as the CVI does not include physical risk factors from extreme heat (or heat index). Whatever the prediction and vulnerability estimation, the fact remains that heatwaves have become more frequent, prolonged and extreme in the recent years.

The government has taken some measures to tackle the problem. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) has framed the National Guidelines on Heat Wave Management for state governments and other stakeholders to help develop their respective heatwave management plans. India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare issued a heatwave health advisory to all states and union territories as temperatures soared in many parts of the country in 2023. Similarly, the National Centre for Disease Control has a host of policy resources on heatwave management preparedness, early warning system, and infrastructure interventions. More significantly, the government has launched the Heat Action Plan (HAP) including a variety of measures to prepare for heatwaves, respond to heatwave related disasters, and post-heatwave responses for state, district, and city government departments. While this is a welcome step in the right direction, there are many shortcomings in the plan according to a recent assessment by an independent Delhi-based think-tank, the Centre for Policy Research. The assessment found that most HAPs are not context specific, are underfunded, legally weak, and fail to identify the vulnerable populations.

As India is predicted to face more severe heatwaves in the coming years, heat action plans need to be mainstreamed into all development and poverty alleviation policies. Just as the poor need employment, education, and food security, there has to be a recognition of their right to safety from heatwaves (along with other climatic disasters). The government must heed the critical assessments coming from the scientific community and upgrade its policies to make them effective in the face of heat crises. Dealing with heatwaves long term will require a bolstering of climate finance geared towards strengthening adaptation technologies and capabilities. India as a welfare state has enormous responsibility and challenge to secure such facilities as cooling energy, clean water for drinking and sanitation use, and adequate shelter for all especially in the context of changing climate and rising temperatures.

Citizens, on the other hand, need to hold their leaders accountable to ensure their security from climate impacts such as heatwaves for which climate change education is inevitable. This would push climate change into the national political agenda. Meanwhile, the government must desist from underestimating the challenge of heatwaves and accord the primacy it deserves for the sake of the safety and security of the millions who still live in close proximity to the elements.

Related articles:

India's G20 Presidency: Can it reshape international climate politics? (3-minute read)

India at COP-27: Did it prevail? (3-minute read)

Climate change and the tribal communities of Manipur, India (3-minute read)

Robert Mizo is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the Department of Political Science, University of Delhi, India. He holds a PhD in Climate Policy studies. His research interests include Climate Change and Security, Climate Politics, Environmental Security, and International Environmental Politics. He has published and presented on the above topics at both national and international platforms.