Contemporary Peace Research and Practice By Chung-in Moon | 08 January, 2023

Fraught Shift From ‘Asia-Pacific’ To ‘Indo-Pacific’

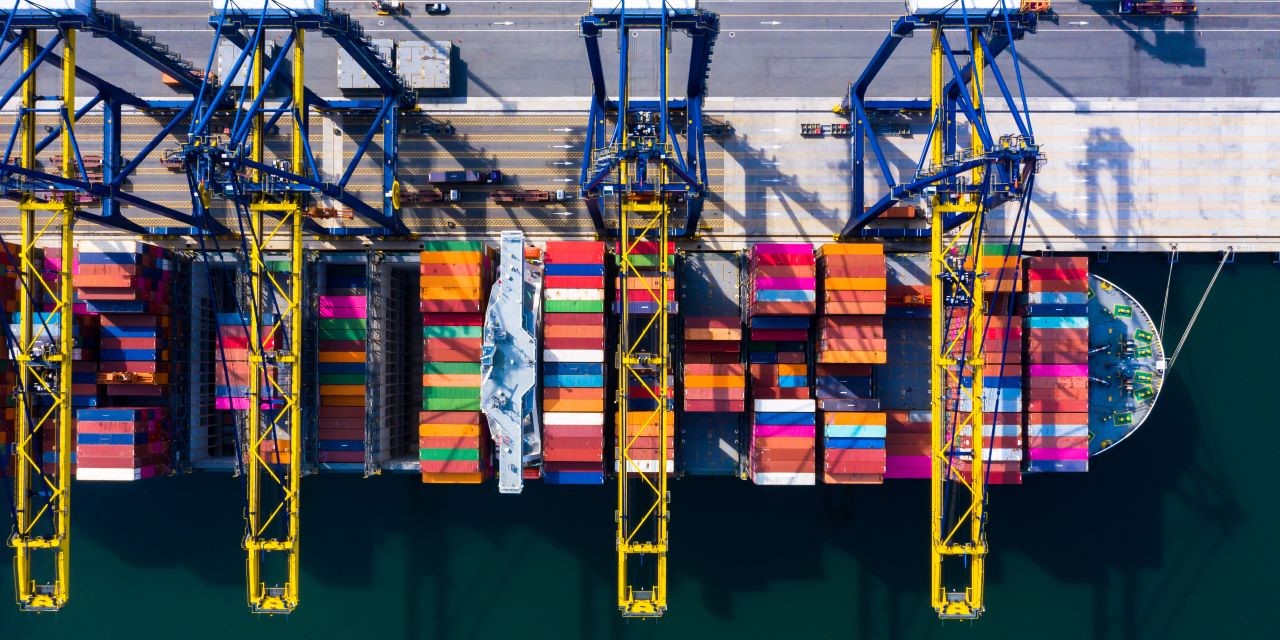

Image: Avigator Fortuner/ Shutterstock

This article is the text of a speech Moon Chung-in delivered at the Beijing Xiangshan Forum in November, which was subsequently published by China US Focus and in the Asia Times. It is republished with the permission of the author.

How to de-risk a lexical change that represents dangerous trends: fragmentation, decoupling and confrontation

I belong to the generation of “Asia-Pacific,” and am rather a stranger to the new idea of “Indo-Pacific.” But nowadays, wherever you go–Europe, Japan, South Korea, the United States and even Southeast Asia–“Indo-Pacific” has become the dominant theme.

In my opinion, the Indo-Pacific concept is very much based on the traditional American maritime strategy. The concept of Asia-Pacific, by contrast, originated from the combination of maritime and continental thinking for peaceful co-existence in our part of the world.

China and Russia–two continental powers–have customarily been included in the Asia-Pacific region, as seen in their membership of APEC. But I now see that the Indo-Pacific concept is radically replacing the Asia-Pacific one, and the Asian continent is disappearing from geopolitical maps (if not geographic ones).

Consequently, confrontation between the US-led Indo-Pacific and the old Asia-Pacific region has become more visible than ever before. It is a bad omen for peace, security and stability in our part of the world. That’s my starting proposition.

My second proposition is that South Korea is in a very difficult situation because of growing tensions between Beijing and Washington. Geopolitical confrontation and economic competition between the two powers, particularly in the areas of trade and technology, have been intensifying. A clash of values between liberal and illiberal states has also become visible, reminiscent of the old Cold War.

South Korea faces a serious dilemma of choice in this bilateral confrontation. Pressures have come mostly from the US side. From a geopolitical point of view, Washington has been pushing Seoul to embrace the Indo-Pacific strategy and to cooperate with the Quad and AUKUS, aiming to encircle China.

Although the US is its most important ally, South Korea is not in a position to antagonize China. In the geo-economic arena, the US has been seeking to decouple China from global supply chains. South Korea joined the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and has been strengthening economic ties with the US. But China remains Seoul’s largest trading partner, accounting for 25% of its total trade volume.

Therefore, it is not easy for South Korea to join the decoupling effort wholeheartedly.

Washington has also been urging Seoul to deepen bilateral technology cooperation at the expense of China. Take semiconductors. The Joe Biden administration has wanted South Korea’s leading semiconductor manufacturers to invest in the US and divert away from the Chinese market, within the framework of the American Chip 4 initiative.

But these companies export about 60% of their products to China (40% to the Chinese mainland, 20% to Hong Kong), while importing almost 60% of chip-related critical materials from China. Therefore, they cannot easily discard China.

And in the area of values, I see tensions. The US has been championing a liberal coalition to fight against illiberal states such as China and Russia. South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol’s government has given the impression that it has joined the liberal coalition by emphasizing freedom, human rights and democracy.

Such a stance could pose a major problem in dealing with China in the years to come.

All these developments are worrisome. The polarisation of the international system and the rise of bloc diplomacy in the region could bring major security, diplomatic and economic dilemmas to South Korea. And we cannot anticipate security, stability and peaceful development in this part of the world under such a devolving regional order.

What should be done? My basic idea is this: First, I think that there has got to be a restoration of the Asia-Pacific concept.

The Indo-Pacific is associated with the logic of bloc diplomacy, exclusivity and the geopolitical division of maritime and continental powers. This makes the disappearance of “Asia” troublesome for all Asians. Therefore, it is important for us to reassess the meaning and implications of the Indo-Pacific more critically, and revalue the traditional Asia-Pacific concept for inclusiveness, cooperation and stability.

Second, cooperative security needs to be re-energized. Now we see the big clash in this part of the world between America-centered collective defence based on alliances and China’s vision of a collective security system based on the United Nations Charter and multilateral security cooperation. To overcome such tensions and subsequent instability, we need to re-energize cooperative security while enhancing preventive diplomacy.

Third, I would also like to highlight the urgency of open regionalism. The Indo-Pacific economic framework; the logic of decoupling, reshoring, friend-shoring; and Chip 4 – all involve closed regionalism.

Closed regionalism contradicts basic norms, principles and rules of the liberal international trading order that the United States has created and sustained. We should return to open regionalism.

Although its performance has been rather dismal, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) is a good example of open regionalism. Even the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a multinational free-trade area, is based on the concept of open regionalism. Thus, the current pattern of closed regionalism is really going against the stream of history.

Fourth, multilateralism must be resuscitated. The world is becoming fragmented. In a fragmented world, we cannot find harmony, stability and peaceful development. It is necessary for us to return to the basic norms, principles and rules of multilateralism in order to avoid a fragmented world.

I really want to emphasize the importance of preventing a clash of civilizations. The Western idea of dividing the world into liberal and illiberal states is extremely misleading and even destabilising. Boosting tensions and conflicts between the two blocs is even worse. Every society has its own cultural and historical contexts, and we need to learn how to respect the differences and live harmoniously.

Finally, mutual respect and strategic empathy should guide our terms of engagement. That is the best way to enhance peaceful co-existence among different civilizations. Mutual respect comes from strategic empathy. When we put ourselves in the shoes of others, we can have a better understanding of their point of view. That reduces potential for misunderstanding and conflict.

I think that such inter-subjective understanding is the surest way to peaceful co-existence, harmony and common prosperity.

Chung-in Moon is professor emeritus at Yonsei University in South Korea. He is the chairman of Sejong Institute. He previously served as the special advisor for unification, diplomacy and national security affairs for President Moon Jae-in (2017-2021) He is also vice chairman of the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (APLN) and editor-in-chief of Global Asia, a quarterly journal in English.