Climate Change and Conflict By Teall Crossen | 13 October, 2022

The Climate Dispossessed are not Refugees

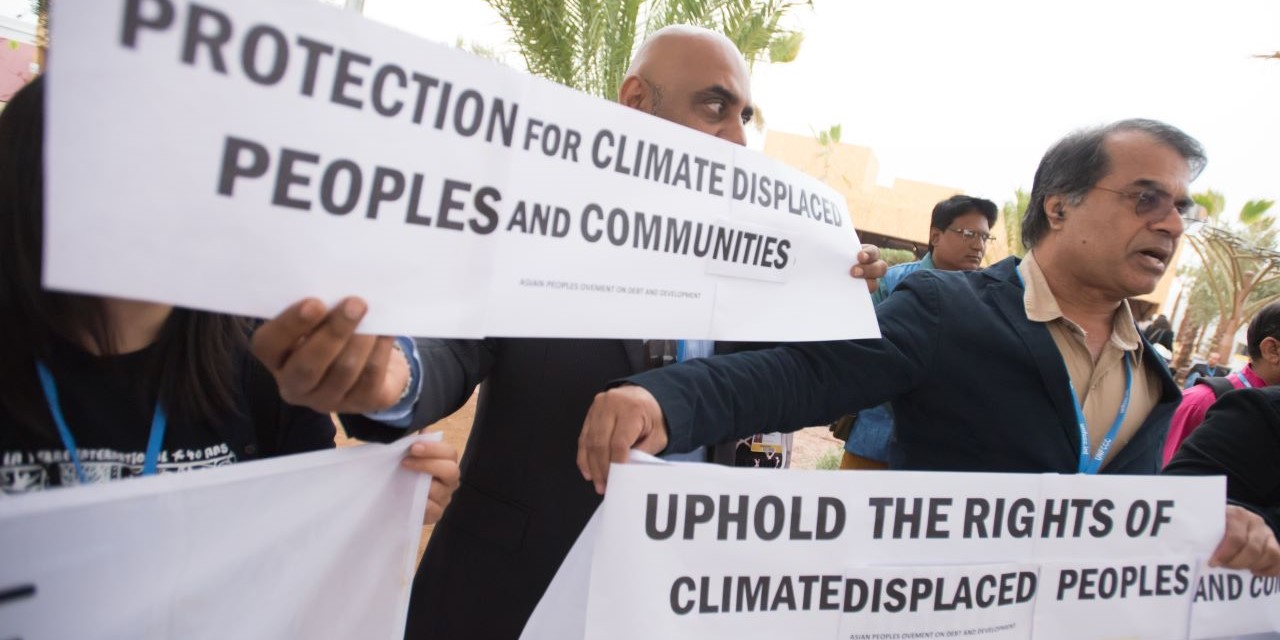

Image: Ryan Rodrick Beiler/Shutterstock

Let’s be clear, people displaced by climate breakdown are not climate refugees under international law. They are not being forced from their countries because of persecution by their own government. Nor are they migrants. They are not leaving in search of work or education, or to be closer to family. Rather, many millions of people are likely to be dispossessed from their homes by the choices of other countries to continue to pollute the atmosphere, without a legal framework to protect them.

In the past, Bangladesh and the Maldives have both called for the Refugee Convention to be extended to protect people displaced by climate change, without success. The UN Human Rights Committee has rejected a claim against New Zealand for deporting Ioane Teitiota back to Kiribati, despite rising seas and other climate damage imperiling his life. While a pathway to safety from deportation in the future may be possible under international human rights law, there are no guarantees, and no enduring solution on the horizon for the millions of people at risk of being dispossessed by climate damage.

Forced relocation of communities is already happening internally in the Pacific region. Recent floods in Pakistan highlight the gravity and immediacy of the crisis, with millions of people displaced from their homes across a country that is currently, literally, drowning. Without urgent and deep emission cuts beyond the commitments in the Paris Agreement, entire nations, particularly those in the Pacific region, are in jeopardy.

The international legal system is ill-equipped to respond to climate displacement – of both people and countries. Deeply troubling questions remain unanswered. How would international law protect the sovereign rights of a country destroyed by climate impacts? What would the legal status be of citizens from an island country no longer habitable, and could the country exercise their sovereignty elsewhere? Calls have been made for new norms to fill the legal void.

But, in advocating for an international legal regime to protect the climate dispossessed, we admit that it is too late to abate the warming climate. We concede that climate displacement across international borders is inevitable. This approach comes with major hazards. When we plan how to provide for people threatened by climate displacement, we provide an excuse to continue to pollute the atmosphere; it privileges polluting countries where displacement is not a serious threat and entrenches unequal global power dynamics. It appears cheaper, and likely easier, to look at migration as a climate solution, rather than giving up our addiction to climate pollution.

Islands have been thought dispensable in the past to further economic progress. Following the Second World War, most of the people of Banaba Island in what is now Kiribati were relocated to Fiji to enable the colonial government to expand phosphate mining operations. Similar plans were made to relocate the entire population of Nauru to Curtis Island off the coast of Australia, again to allow the expansion of phosphate mining to enhance the profits accruing to Australia, Britain and New Zealand from industrial agriculture. Nauruans rejected the proposal, preferring to maintain their national sovereignty and identity.

Of course, there is also a danger in not planning for all eventualities, including the possibility of cross-border displacement. Tuvalu, one of the most vulnerable Pacific countries to climate change impacts has called for a United Nations resolution to establish a legal process to protect the human rights and lives of those displaced by climate change. There is also ongoing work by the Taskforce on Displacement under the Climate Convention, including in relation to enhanced cooperation for displacement and planned relocation. The Taskforce seems to be taking only tentative steps, however, in recognition that its very existence admits failure. The ultimate goal of the Convention is to prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system, and the likely prospect of millions of displaced people seems beyond dangerous.

Any approach to climate displacement, including the development of new legal norms, needs to be firmly grounded in existing international law. The Refugee Convention does not provide answers for the climate dispossessed. The liability of polluting countries for climate damage, however, is more instructive as a foundation. Countries most at risk of forced displacement are the least responsible for causing rising temperatures and the ensuing loss and damage. Therefore, providing climate reparations to vulnerable countries so that remaining in their own territories is a viable option is a far better approach, that will protect both people and the sovereign identity of countries at risk.

Teall Crossen is an environmental barrister with two decades of experience advocating for environmental justice in Aotearoa and overseas. She has worked for Forest & Bird (New Zealand), Greenpeace International, and served Pacific Island countries at the United Nations. Teall is the author of The Climate Dispossessed: Justice for the Pacific in Aotearoa?