Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament By Ramesh Thakur | 05 May, 2022

Double Standards are Normal in Foreign Policy

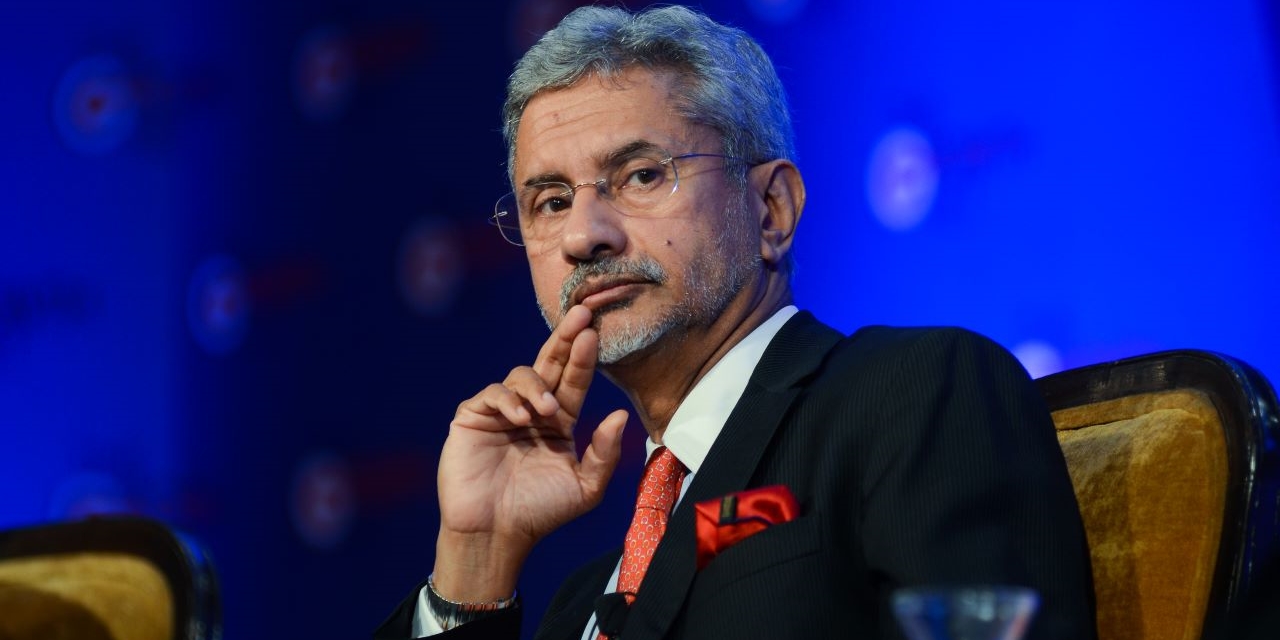

Image: India’s Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar Naveen Macro/Shutterstock

This article was first published in The Strategist on 3 May 2022.

What is it about some Westerners that makes them so singularly lacking in self-awareness as they assume a position of moral and intellectual superiority to issue condescending pronouncements on non-Westerners? In their chapter in the 1999 book The power of human rights, Thomas Risse and Stephen Ropp wrote: ‘Pressure by Western states and international organizations can greatly increase the vulnerability of norm-violating governments to external influences.’

I can still remember being startled, when I first read that sentence, by the unconscious arrogance it betrayed in dividing the world into non-Western governments as errant norm-violators and Western governments as virtuous norm-setters and norm-enforcers. When I worked at the United Nations, I lost count of the number of times African and Asian diplomats complained about the continued hold of the white man’s burden on Westerners’ dealings with the rest of the world.

Edward Luce pointed out in the Financial Times on 24 March that in saying Russia has been ‘globally isolated’ over Ukraine, the West ‘is mistaking its own unity for a global consensus’. True, 141 of the UN’s 193 member states voted to condemn Russia’s invasion in a General Assembly resolution on 2 March. But the 52 non-Western countries that didn’t, including half the African countries, account for more than half the world’s population and include democracies like Bangladesh, Mongolia, Namibia, South Africa and Sri Lanka. Because India is the most prominent and consequential of these, many commentators continue to ask: ‘Why does India get a free pass for supporting Russia?’

By contrast, and echoing Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s earlier careful differentiation of India’s public neutrality on the Ukraine war from China’s (there’s no moral equivalence between India’s and China’s abstentions on UN votes on Ukraine, ‘not even remotely,’ he said), during his recent visit to India, UK PM Boris Johnson noted that Indian PM Narendra Modi had intervened ‘several times’ with Russian President Vladimir Putin ‘to ask him what on earth he thinks he is doing’. India, he added, wants peace and not Russians in Ukraine. He was followed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who expressed keen interest in partnering with India in renewable energies as a way of Europe’s ‘diversifying away’ from Russian oil and gas.

These views validate the claim by an Indian official, and broaden it to Western capitals more generally, that there’s been ‘a belated, but grudging, acceptance of India’s position within the US administration’. Such official understanding of India’s careful balancing act and nuanced policies is absent from much public commentary.

Foreign policy is not about virtue-signalling morality but about acting in the best interests of citizens. Every country’s policy is based on a mix of geopolitical and economic calculations (realism) and core values and principles (idealism). Consequently, no country’s policy is consistent and coherent, and none is immune from mistakes, hypocrisy and double standards, even if some are guilty more often and more gravely than others. It cannot be, therefore, that when Western governments downplay values, as in the long-running and brutal Yemen conflict, it’s realpolitik, but silence about atrocities in Ukraine by others is complicity with evil.

India’s Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar pointedly remarked on 11 April in Washington that since sanctions were imposed by NATO on Russia, India’s monthly oil imports from Russia were probably less than European energy imports in one afternoon. At the prestigious annual Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi on the 26th, Jaishankar gave similarly sharp answers to questions from the foreign ministers of Norway and Luxembourg. Last year, he reminded them, the rules-based order came under threat in Asia after the West’s hasty departure from Afghanistan and Asians were left to deal with the aftermath. India’s security interests were heavily impacted by the chaotic withdrawal that was all exit and no strategy. On 22 April, the UK’s Daily Telegraph reported that since the EU arms embargo on Russia imposed after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, France and Germany had sold €273 million worth of arms to Russia that were likely being used in the war in Ukraine.

On 24 April, Morrison said a Chinese military base in Solomon Islands would be an unacceptable red line. A White House statement after President Joe Biden’s top Pacific adviser Kurt Campbell met with Solomons PM Manasseh Sogavare said that if ‘a de facto permanent military presence, power-projection capabilities, or a military installation’ were to be established there by China, the US would have ‘significant concerns and respond accordingly’. This is not dissimilar to how Russia reacted to its red lines being crossed by Ukraine and NATO, as South African President Cyril Ramaphosa noted. The Solomons are 1,700 kilometres from Australia’s coast, while Russia and Ukraine share a land border and Kyiv is only 755 kilometres from Moscow (directly comparable to Ottawa–Washington).

There’s a more complete understanding among the Australian, British, European and US governments today that India’s dependence on Russian arms is a legacy posture that doesn’t reflect current trajectories. The dependence arose as much from restrictive US arms export policies in the past as from India’s preferences. The visible deficiencies of Russian arms in the Ukraine war will accelerate India’s shift away from them. Russia’s reduced economic weight under the impact of Western sanctions will also make it a less attractive partner.

Indian statements on the Russian invasion and atrocities against civilians have hardened over time, albeit without naming Russia. India offers possibilities for reducing Western dependence on the Chinese market and factories (cue the recent Australia–India trade-liberalising agreement) and also on Russian energy. And India is critical to an array of Western goals in the Indo-Pacific.

After the 2+2 ministerial meeting in Washington on 11 April, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin described the US–India relationship as a ‘cornerstone of security in the Indo-Pacific’. Secretary of State Antony Blinken acknowledged that India–Russia relations developed in the decades when the US ‘was not able to be a partner to India’. Today, however, the US is ‘able and willing to be a partner of choice with India across virtually every realm: commerce, technology, education and security’. Most Indians reciprocate that sentiment, but India can better help advance Western goals, including as a source of influence over other countries, as a demonstrably independent actor in world affairs than as a mere US cypher.

Ramesh Thakur, a former UN assistant secretary-general, is emeritus professor at the Australian National University, Senior Research Fellow at the Toda Peace Institute, and Fellow of the Australian Institute of International Affairs. He is the editor of The nuclear ban treaty: a transformational reframing of the global nuclear order.