Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament By Ramesh Thakur | 13 January, 2022

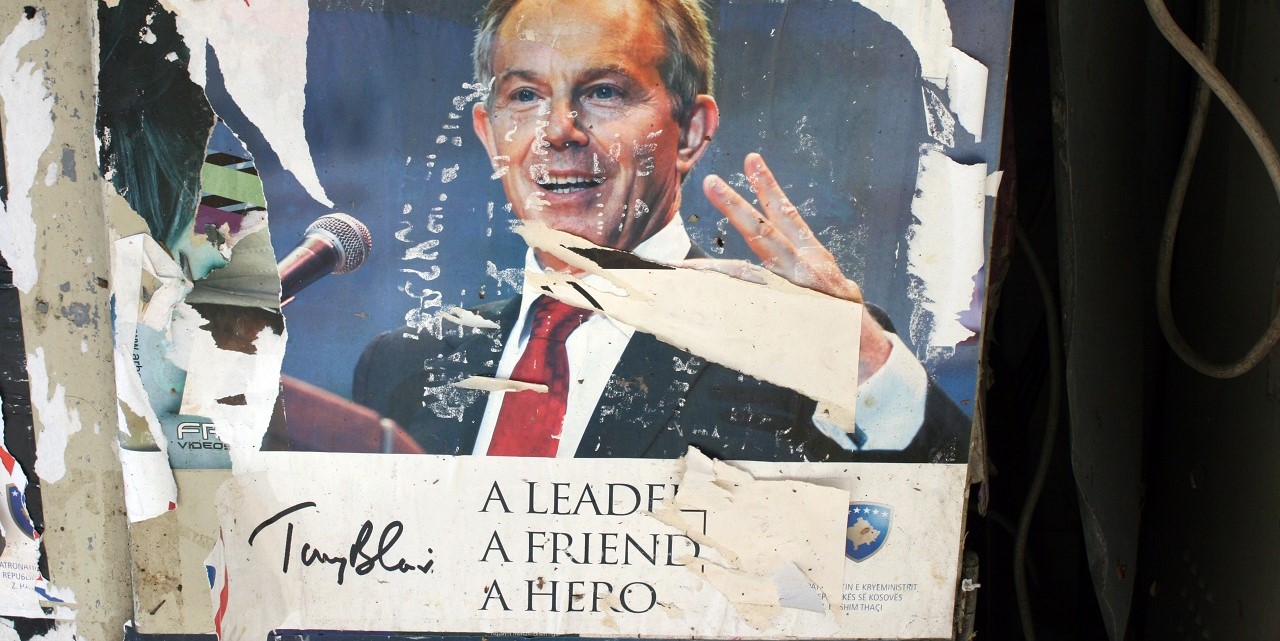

Blair Knighthood Shows How History Does Mockery

Illustration: Quinn Dombrowski/Flickr

This article was first published in The Strategist on 6 January 2022 and is reproduced with permission.

Proving that history does irony, banks that once feared masked robbers now fear mask-free customers. But does history also do mockery? The 1984 Nobel Peace laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu passed away on Boxing Day in Cape Town. Almost a decade ago, Tutu refused to share the stage with former British prime minister Tony Blair in Johannesburg, saying he should be in the dock in The Hague answering for war crimes.

Tutu pointedly asked why African leaders should be arraigned before the International Criminal Court while Blair joined the international speakers’ circuit. Recalling the ‘immorality’ of the Anglo-US invasion of Iraq, he wrote in The Observer: ‘[I]n a consistent world, those responsible for this suffering and loss of life should be treading the same path as some of their African and Asian peers who have been made to answer for their actions in The Hague.’

Within a week of Tutu’s death, Blair featured in the New Year’s Honours list as a Knight Companion of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. Lindsey German, convener of the Stop the War Coalition, was ‘amazed’ to hear the ‘incredible’ news: ‘I think it’s a kick in the teeth for the people of Iraq and Afghanistan, and a kick in the teeth for all the people who protested against the war in Iraq and who have been proved right.’ Andrew Pierce wrote in The Daily Mail of ‘the greed, vanity and folly that taints his true legacy’. Royal appointments to this order don’t require approval by the prime minister or parliament. By 4 January, a petition calling on the Queen to rescind the knighthood had garnered more than 650,000 signatures.

Iraq will forever stand as Blair’s political epitaph, an enduring metaphor for official dissembling and manipulation of evidence and public opinion to take a country into an illegal war of aggression. In The march of folly, Barbara Tuchman argued that historical figures made catastrophic decisions contrary to the self-interests of their countries that were held to be damaging to those interests by contemporaries and for which alternatives were available at the time.

The Iraq War proved to be one of the most consequential foreign policy blunders of all time, with a yawning chasm between the vision dreamed, the goals pursued, the means used, the price paid in blood, treasure and reputation, and the results obtained. The nearly two decades since 2003 have done little to soften the criticism and much to validate and deepen it.

The war set in train a sequence of events that has turned the entire region from Afghanistan to Libya into an anarchic mess of ravaged countries, broken societies and dysfunctional polities. The invaders left behind a country radically different from the one envisaged when it was attacked. Occupation proved different from and more difficult than invasion, and nation-building proved more challenging and protracted still.

The Chilcot report on the reasons for and management of the UK’s role in the Iraq War further seared conventional wisdom deep into the public consciousness. The report noted that:

[T]he UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted. Military action at that time was not a last resort …

The judgements about the severity of the threat posed by Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction—WMD—were presented with a certainty that was not justified.

Despite explicit warnings, the consequences of the invasion were underestimated. The planning and preparations for Iraq after Saddam Hussein were wholly inadequate.

Predictably, Blair rejected the judgement of Chilcot.

The principal author of the war was US President George W. Bush, but Blair was an essential enabler. Without his visible and robust international backing, Bush might not have garnered the requisite domestic support to carry the day. In the foreword to the ‘dodgy dossier’ of September 2002, Blair wrote that Saddam’s ‘military planning allows for some of the WMD to be ready within 45 minutes of an order to use them’. This turned out to be fake news but vital to rally the party, the parliament and the nation behind the decision to go to war.

British intelligence services informed Blair in April 2002 (a year before the war) that Saddam had no nuclear weapons and any other WMD would be ‘very, very small’. The Chilcot inquiry was told that Blair accepted this but converted to Bush’s way of thinking after a visit to his ranch in Crawford, Texas. This is corroborated in the infamous Downing Street memorandum written by British foreign policy aide Matthew Rycroft on 23 July 2002 summarising a briefing by Richard Dearlove, head of MI6. Bush was determined to go to war and military action was seen as inevitable. But British officials didn’t believe it was legally justified, so ‘the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy’.

Blair’s ‘spinmeister’, Alastair Campbell, orchestrated a campaign of denigration of critics querying the evidence. Those who questioned the lack of evidence to invade Iraq were demonised as apologists for the Butcher of Baghdad. Nor should Blair be absolved of partial responsibility for the death by suicide of the British scientist David Kelly. As David Hencke wrote in The Guardian in October 2010, the Blair government engaged in ‘appalling behaviour’ to distract attention from the lies and deceit about Iraq’s WMD and the threat they posed to Britain by highlighting Kelly’s ‘crime’ of lying about speaking to a BBC journalist. An honourable man was hounded to death to shield the government’s deceptions.

Blair also shares culpability with Bush for going to war without a clear exit strategy. Instead of a quick victory in Iraq followed by consolidated democratic regimes in a stable region and an orderly withdrawal, the US found itself in a quagmire and eventually went back home an exhausted and vanquished conqueror, its will to intervene abroad sapped.

Blair calls to my mind a character in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House: ‘Sir Leicester is generally in a complacent mood. When he has nothing else to do, he can always contemplate his own greatness. It is a considerable advantage to a man, to have so inexhaustible a subject.’ Perhaps Blair is mocking history instead.

Ramesh Thakur, a former UN assistant secretary-general, is emeritus professor at the Australian National University and director of its Centre for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament. He is the editor of The nuclear ban treaty: a transformational reframing of the global nuclear order, published by Routledge in early 2022.