Social Media, Technology and Peacebuilding By Medinat Abdulazeez Malefakis | 29 January, 2021

Using Social Media and #ENDSARS to Dismantle Nigeria’s Hierarchical Gerontocracy

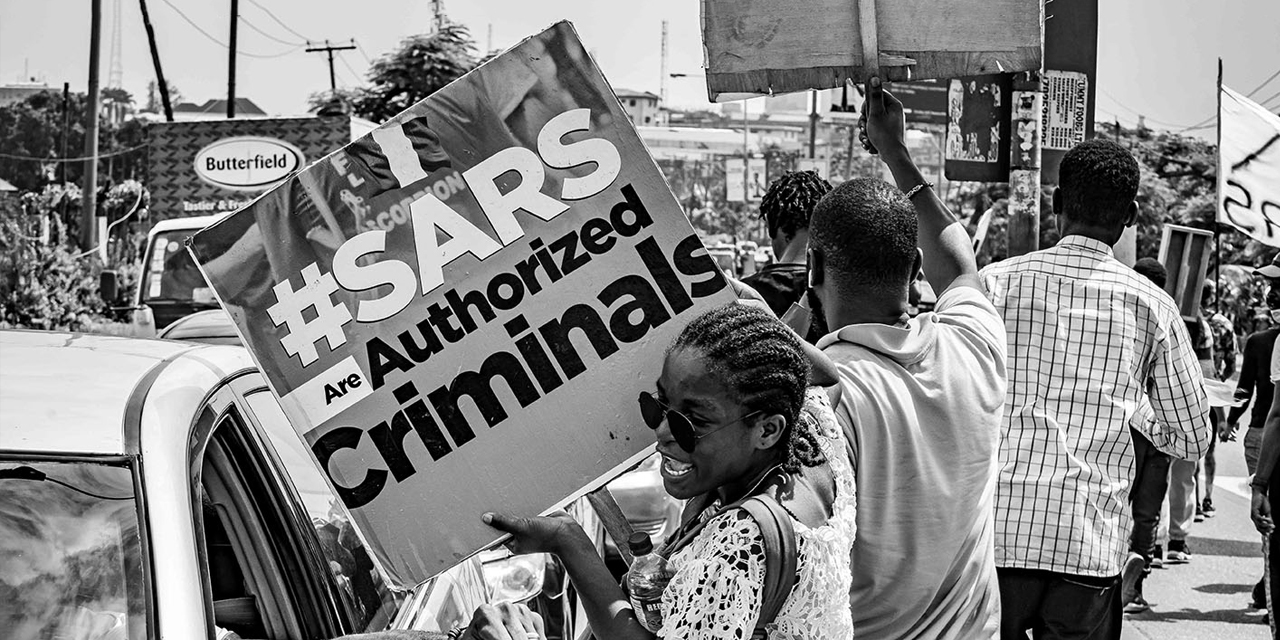

Photo credit: TobiJamesCandids - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

On October 3 2020, a video of a Nigerian Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) attack on a victim began to spread on social media, showing a young man shot and SARS operatives driving away in a Lexus SUV. The attack sparked public outrage, and the #ENDSARS hashtag became the most popular Twitter trend in the world, garnering about 28 million tweets on the first weekend. Young people took to the streets, beginning on October 8 2020, to peacefully demand the abolition of SARS.

Every year since 2017, a particularly gruesome SARS attack has led to online agitations with the Twitter hashtag #ENDSARS, calling for the unit to be scrapped. The Nigerian government and the police force have sometimes ignored these calls, and at other times claimed an overhaul of the unit, but the human rights violations being committed by SARS operatives continued.

Everything about the latest wave would be different. For the first time since 2017, #ENDSARS would develop from an online agitation to a full-fledged offline protest, starting in Lagos on October 8 after celebrities called for a peaceful march in the city and spreading to other parts of southern and eastern Nigeria, including Nigeria’s federal capital, Abuja.

SARS was a unit of the Nigerian police set up in 1992 to fight violent crimes including robbery and cyber-crimes. Over time, however, the unit became a force of terrorising law enforcement. Amnesty International documented at least 82 cases of torture, ill treatment and extra-judicial execution by SARS between January 2017 and May 2020.

SARS targeted youths aged 15-35, profiling them based on the way they dressed, the cars they drove, the phones they used, their sexual orientation, and even their job types. A young man with an iPhone, an expensive car, ripped jeans, piercings, dreadlocks or a tattoo would be stopped by SARS operatives on the premise that, at this age, a young person is not expected to have such luxuries, and is therefore either an internet fraudster or an armed robber. Without being arrested or charged with any specific crimes, SARS operatives have indiscriminately searched phones, going through text messages from the banks of ‘arrested’ persons to see their account balances, and so on. They have been known to extort money from their victims, marching them at gunpoint to ATMs to withdraw all their cash. SARS operatives also arrested, tortured, detained and killed indiscriminately, carting away their victims’ cars, phones, laptops and cameras.

The #ENDSARS movement is led mainly by young people who direct their anger first and foremost against SARS. On a more general level however, an end to police brutality was one of many calls through which Nigerian youths aimed at dismantling the country’s hierarchical gerontocracy. This latest wave of #ENDSARS protests morphed into an identity conflict between the young and the old in Nigeria.

Young people used the street protests to aim their displeasure and exasperation at the hierarchal “status quo” of the Nigerian society which posited an “authoritarian odour”, where older people are supposed to be highly regarded for their wisdom and knowledge of community affairs. Of Nigeria’s population of approximately 200 million, about 135 million are under 30 years. As the SARS protests progressed, many of the youths voiced the opinion that the older generation was the real cause of Nigeria’s societal problems because they had been cowardly, never confronting the leadership of the country, and continuously praying away their problems. The elderly and political elites, on their part, viewed the youths as inexperienced, the generation that is always in a rush, always on the internet, and addicted to their smartphones. This is why they systematically do not allow the younger generation to participate in politics: they are regarded as immature and ill-suited for political office.

When these same youths used their so-called addiction to the internet to demand justice, the reaction to their demands was met with high-handedness, violence, and disdain. The elderly and the elites, typified by the Nigerian government and political office holders, acted on age-long traditions of gerontocracy and entitled respect. First, they ignored the protests as the usual rants of the young generation, then reacted condescendingly with the usual lip-serviced reforms, including unveiling a new police unit (Special Weapons and Tactics – SWAT) to replace SARS. When protesters would not fall for the old gimmicks, they were violently repressed. On 20 October 2020, the 12th day of the protests, the government ordered the military to open fire on the peaceful protesters, killing about 12 of them in Lagos (these are only the official numbers).

The protests in Nigeria against SARS demonstrate how social media can be galvanised as a tool to challenge established norms and demand for societal change. The use of digital technology changed the rhythm of the movement, from an online yearly banter to the most efficient and engaging youth-led movement Nigeria has seen in a long time. There was no discernible leadership in the decentralised structure of the movement. Twitter was used daily to map out specific locations where young people would converge, for example, at the Lekki Toll Gate. Social media was also used to share images and progress reports of the protest in Lagos before it spread to other parts of the south. Social media was also used to call the attention of international celebrities, politicians, diplomats, media corporations and others, embarrassing the Nigerian government into reacting and paying attention to the protesters and their demands. Social media also became, at a point, one of the only sources of information about the movement as mainstream media in Nigeria were not reporting on the protests.

Digital technology was also pivotal in funding the protests. Local tech start-ups, mostly owned and run by young people, helped with crowdfunding and donation links, and over US $380,000 was raised for the movement.

The government reacted as it did to the ENDSARS protests, including President’s Buhari’s refusal to acknowledge the Lagos massacre, because the protests (in organisation and effect) had shattered Nigeria’s culture of deference to the elderly and elites. As the youths were not expected to question the actions of elders/elites by demanding social justice, ENDSARS had defied the traditional order of age-based hierarchy, and the powers that be would not tolerate it.

While this wave of #ENDSARS protests ended tragically, Nigerian youths realised that social media can be a defining force in organising societal campaigns, and elders will not always have the best solutions. The youths now have an answer to the saying: “what an elder can see while sitting, a child cannot see it even if she/he climbs to the rooftop.” The youths have decided to use ‘drones’ to see such! This is an awakening that is sure to be appropriated in the search for real reforms in the future.

Medinat Abdulazeez Malefakis is an Information Analyst at ACAPS. Dr Malefakis obtained her Doctorate in International Studies from University of Zurich and the Nigerian Defence Academy, majoring in Terrorism and Humanitarian Displacement. Dr Malefakis’ research interests are terrorism, violent extremism, religious fundamentalism, humanitarian displacement (refugees and IDPs), social and violent conflicts, post-conflict resettlement, rehabilitation and reintegration.