Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament By Herbert Wulf | 10 May, 2021

The Renaissance of Geopolitics (in Europe)

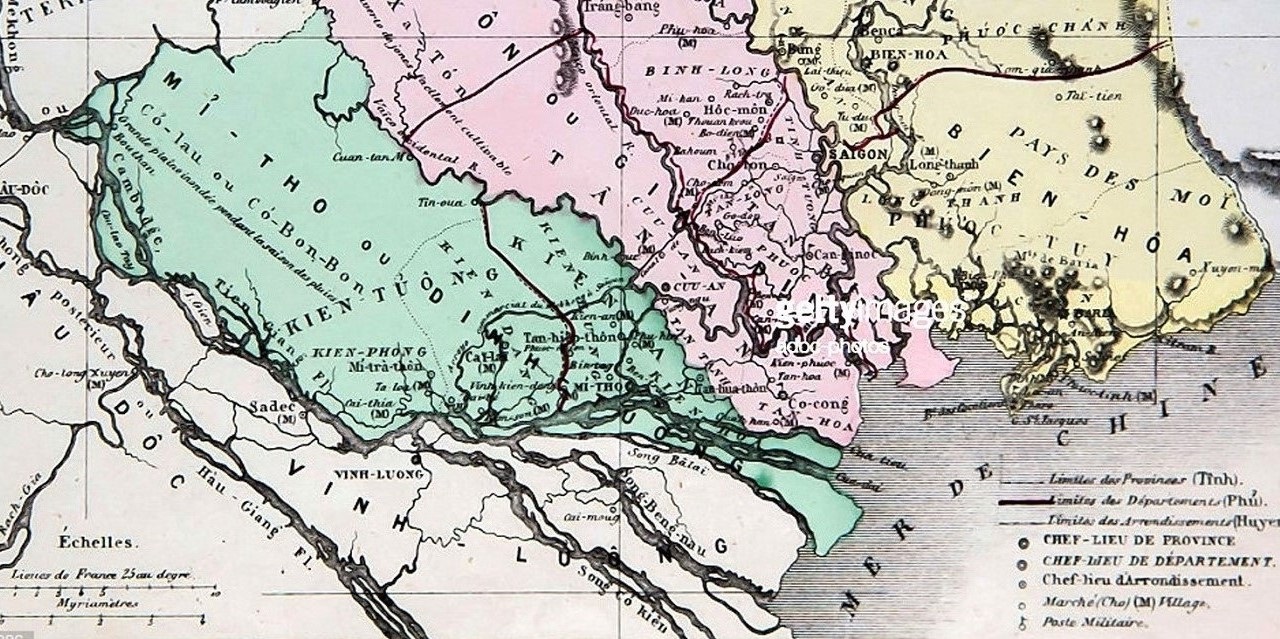

Image: Manhhai/Flickr

Three decades ago, at the end of the East-West antagonism, the old world order was gone and the trend for new formats unclear. Different and contradictory prognoses were made. Famously, Francis Fukuyama predicted the end of history and the triumph of capitalism and liberalism. In contrast, Samuel Huntington hypothesized that the new era would no longer be characterised by the ideological divide but by a clash of civilisations. And John Mearsheimer, who was worried about the instability in Europe after the Cold War, suggested that prospects for war in Europe would be likely to increase if a multipolar structure emerged. A bipolar system would be more peaceful.

What do we make of these seminal forecasts now? The unchallenged US-led Western dominance is over. Are we approaching a new Cold War between Russia and NATO and a new “great game” of fierce competition and confrontation between major economic and military powers in Asia? After four erratic Trump years, “America is back again” but the perception of China as a competitor, at best, and an enemy, at worst, remains. Irritations during the Trump administration have changed the security narrative in large parts of Europe. The political leadership pushes the EU into what is perceived as its “rightful place” at the high table in the new big power game. Defence and security policy no longer looks at opportunities for negotiations and dialogue; arms control is dead, and a peace dividend has been given up long ago. Power projection and intervention capabilities are the call of the day: from the US to China, from India to Russia, from the UK to the EU. A race for investments in modern military technologies is underway. All measures short of war (and in some cases even war) are explored. These trends are accompanied by the resurgence of geopolitics, the fight for the control of space: geographically, digital and in outer space. The big powers show their presence. These trends are beyond the control of any single nation or alliance. One has to be pessimistic when assessing the future of a war-avoiding international security architecture.

In this global setting of a fluid environment, the EU and other European nations, particularly the United Kingdom after Brexit, are struggling to find their role and its place. EU’s policy makers fear that the EU will be marginalised in the US-China bipolarisation. The political elite, including the EU Commission, wants the EU to learn the language of power. In its own perception, and after a transatlantic normalisation, European leaders see security problems in three areas: Russia’s military actions, the Middle East and the Mediterranean/North African region, and the Indo-Pacific.

In a shift of the political and military balance, NATO moved closer to the Russian border by granting NATO membership to former Warsaw Treaty countries: Poland, the Baltic countries, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Romania and several Balkan countries. In geopolitical terms, the cordon sanitaire is gone. Russia feels threatened and has occupied the Crimea and supports separatist tendencies in Eastern Ukraine. Responses of European governments vis-à-vis Russia are contradictory. Neither the European part of NATO nor the EU have a clear concept or a Russia-strategy. Whenever issues of importance are on the agenda (e.g., EU sanctions to punish the Russian government’s treatment of the opposition or the gas pipeline North Stream 2 for the supply of Russian gas to Germany), controversies prevent a unified response. The pendulum swings between emphasising soft power and dialogue versus harsh reactions to “teach them a lesson”.

European policies regarding conflicts and regional ambitions in the Middle East and the Mediterranean/North African region are similarly erratic, contradictory and inconsistent. Two pressing and interconnected issues—wars and other violent conflicts in and the migration from this region to Europe—should be persuasive reasons for European governments to respond in a unified and combined fashion. The end-result of European reactions is devastating if we look at the response to the wars in Syria, Libya, Yemen and Mali, at foreign and trade policy with the autocracies on the Arabian Peninsula, a possible Turkish membership in the EU or the non-existing asylum policy. Some European governments support the Libyan government, others the opposing self-declared government of General Chalifa Haftar. A European position or a mediating role on the Israel-Palestine conflict: not on the horizon! A clear EU policy for this important European neighbourhood: missing for so long!

Despite these failures in the European neighbourhood, in an act of hubris, the EU and also the UK suddenly “discover” geopolitics. Ursula von der Leyen declared at the beginning of her term as President of the EU Commission: “This will be a geopolitical Commission.” All of a sudden, the Indo-Pacific is their important area of interest and the aim of geopolitics, like Obama’s “Asian pivot”, taking the focus from the European sphere to countries in the proximity of China. The German government just passed their Indo-Pacific guidelines, underlining their political and economic interest in the region. “Global Britain”, the February 2021 reassessment of its power after Brexit, perceives itself as an independent major power, emphasising particularly its naval power. As a signal, the UK government seems determined to send the new aircraft carrier strike group on a flag-flying mission off the coast of China. Is it more than a nostalgic look back at the lost empire? French President Macron pushes for an autonomous (militarily strong) EU vis-à-vis both the US and China. And the EU tries to position itself in this region of perceived systemic rivalry between China and the US.

When considering the ugly history of geopolitics, it is somewhat surprising to see this renaissance in Europe, particularly in Germany. At the end of the nineteenth century the school of geopolitics convinced the German leadership of the need for expansive territorial ambitions in the East. And at the dawn of World War II, the Nazis used the geopolitical term Lebensraum (space for living) to convince an entire nation to accept their horrendous ideology. It seems, the long existing taboo for geopolitics is forgotten in Germany. The belief of geopolitics was, and many policy statements today sound like it, that there are “vacuums” that need to be filled. It is the same attitude the colonial powers had when they divided up other parts of the world. Geopolitical notions constitute an almost deterministic Darwinism. Or, in more modern terms, a zero-sum-game. If we don’t move, others will take advantage. With geopolitics, the multilateral world with international cooperation is far away.

Herbert Wulf is a Professor of International Relations and former Director of the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC). He is presently a Senior Fellow at BICC, an Adjunct Senior Researcher at the Institute for Development and Peace, University of Duisburg/Essen, Germany, and a Research Affiliate at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago, New Zealand. He serves on the Scientific Councils of SIPRI and the Centre for Conflict Studies of the University of Marburg, Germany.