Cooperative Security, Arms Control and Disarmament By Herbert Wulf | 09 March, 2021

Setting New Priorities: The EU Shifts from Civil Peace and Development Projects to Military Policies

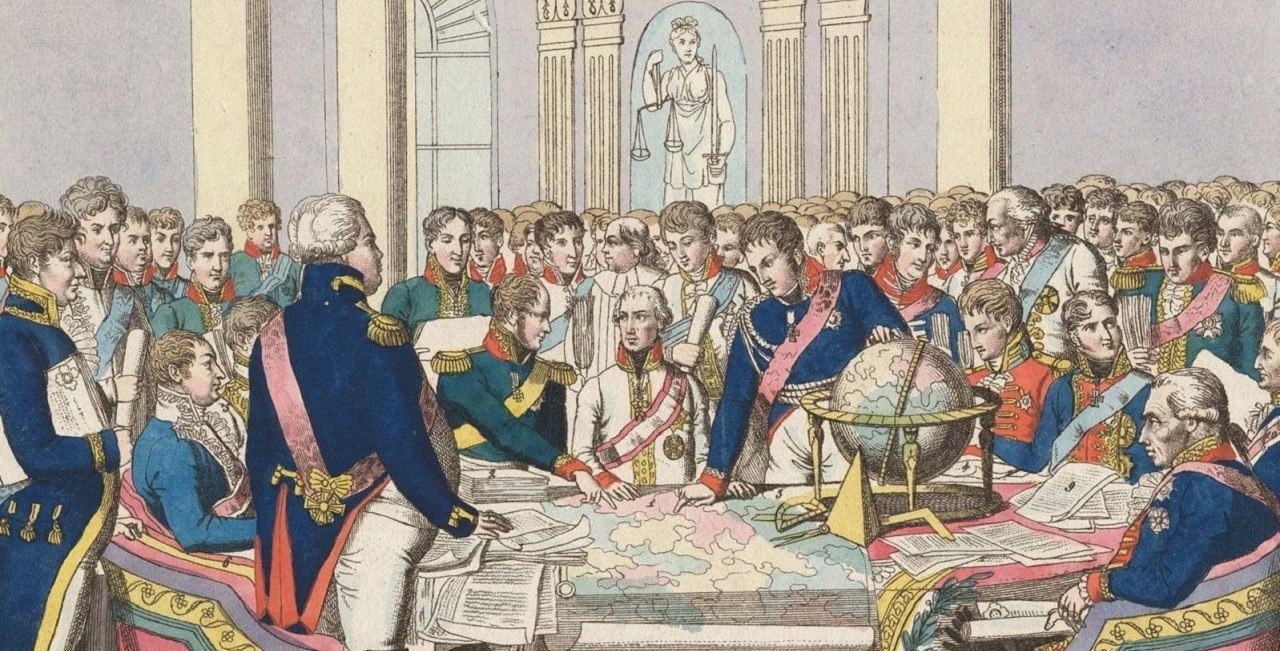

Image: The Congress of Vienna by August Friedrich Andreas Campe

The EU’s foreign and security policy is plagued by unclear concepts, contradictory interests and fierce controversies between its member states. At the moment, priorities are set for a stronger military and defence role. The EU as a “power of peace”, a term popular ten years ago, has been pushed aside and geopolitical ambitions moved into the foreground. This is a retrograde step for international peace and security and especially unfortunate at a time when the UN’s primacy is already under challenge.

In 2012, the EU was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and was particularly praised for its role in bringing about not only an armistice but real peace to Europe, after centuries of being ravaged by bitter armed conflicts. This served as an inspiring example to many other conflict-riven regions. Today, French President Emmanuel Macron repeats his mantra that the EU needs “strategic autonomy”, particularly in terms of military strategy and capability. A global strategy and solving conflicts in the neighbourhood sometimes calls for “hard power”. Loosely interpreted: In the current confrontative world order should the US no longer do the cooking and the EU the dishes? And the EU-Commission assists by calling for a more assertive foreign, security and defence policy. This is often underpinned by geopolitical considerations, assuming that US withdrawal creates a vacuum that must be filled by the EU. On the one hand, there are frequent complaints about the EU's lack of political and military capacity to act in any international crisis. On the other hand, national sovereignty in defence policy is carefully guarded in the various capitals and not transferred to Brussels.

The emphasis on a stronger military role of the EU is faced with two problems: first, not all member states agree to this course and second, given the shortage of resources, this policy will in the long term be at the expense of the so-called “European Peace Facility”. Before Brexit was completed, the UK objected to a strong EU defence role. Now, defence policies are largely promoted in the core countries of the EU, or more precisely, pushed by the French and complemented by the German governments. But many other governments in the EU are not happy to be sidelined. With the EU enlargements, members were added, particularly the Baltic countries, who actually put more trust in NATO for their defence than in the EU. The 27 EU members voice and pursue different policies on such issues as conflict resolution in Syria, Libya and the Ukraine. There is disagreement on how to react to China’s silk road project, on the use of autonomous weapons and most countries in Europe oppose the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), although Austria was a driving force behind the Treaty and Ireland has signed and ratified it. And the role of French nuclear weapons in an EU security policy remains a taboo issue. Thus, the road to an EU policy is far from being clear.

Even the promoters of a stronger military role disagree on its implementation. When the French government talks about the “rediscovery of realpolitik” it has primarily military interventions in mind. And interventions are predominantly intended in Paris to counter terrorism. The German position is different. The German public—with an overwhelming majority opposed to military interventions abroad by the Bundeswehr—is always ‘lectured’ that engagement is necessary in the name of ‘stability’ in the intervened countries. Thus, French troops are engaged in battles, overtly and covertly, e.g., in Mali and through military assistance to the militia of Khalifa Haftar in Libya, while German troops concentrate on training and equipping the security forces in Afghanistan, Mali, Iraq, Horn of Africa, South Sudan and Kosovo. Inconsistency in these approaches is the result. Wolfram Lacher, an advisor to the German government, concludes: “The record of German and French policies in the crisis states of Mali and Libya is disappointing. While German engagement has remained largely ineffective, France's policies have often contributed to further destabilization.” And the EU Battlegroup, a military unit adhering to the Common Security and Defence Policy and in existence since 2007, has never been deployed.

A review of the past European military interventions shows that the EU has been slow and rather restrained in its self-defined responsibilities since the first Operation Artemis in eastern Congo in 2003. Overall, the record of Western military interventions is at best mixed. From Afghanistan (2001) to Iraq (2003) and Libya (2011) to Mali (2013), military successes have been followed by long-lasting instability. All these military engagements are now searching for face-saving exit strategies. The interventions in the Balkan countries (under NATO command)—although also highly controversial—produced better results and some of the countries of former Yugoslavia are now members of the EU.

The EU’s practises in civilian crises prevention and peace promotion are much more positive. Its capacity and potential are enormous. Interestingly, the EU spends much more money on its development programmes, civilian peace missions and democracy policies, mainly in African countries and the Balkans, than on military interventions. EU documentation lists 18 current and almost two dozen completed foreign missions. Two thirds of EU missions abroad are civilian, but only 20 percent of the personnel. The EU budget for 2021-27 allocates almost 100 billion EURO for neighbourhood and development policy, humanitarian aid, human rights, international cooperation and stability. These programmes are much more popular among EU citizens than military interventions. A combination of anti-militarist currents and fear of costly military operations, of dire experiences in the past and the long-lasting or seemingly never-ending military engagements abroad, make the EU’s military ambitions unpopular.

Notwithstanding such past experiences, the primary concern and focus of security debates among the EU elite is now on military interventions, all in the name of a global role for the EU. While defence matters were for many decades a “no-go” for the EU Commission, a change was introduced with the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009 that encourages member countries to cooperate in defence. Since then, the EU-Commission assumes an expanded role and financial resources are allocated for that purpose in the present EU budget. Lobbying for defence has recently even successfully encroached into the peace facility. Despite its name, the “European Peace Facility” can also be used to fund military intervention.

Despite an overall positive impact, the “European Peace Facility” could be further strengthened by better coordinated UN-EU efforts and not getting mixed up with geopolitical and military ambitions. Instead of holding on to the pledge of spending 2% of GDP on defence, the EU should strive for meeting the long-promised goal of allocating 0.7 % of GDP on development.

Herbert Wulf is a Professor of International Relations and former Director of the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC). He is presently a Senior Fellow at BICC, an Adjunct Senior Researcher at the Institute for Development and Peace, University of Duisburg/Essen, Germany, and a Research Affiliate at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago, New Zealand. He serves on the Scientific Councils of SIPRI and the Centre for Conflict Studies of the University of Marburg, Germany.