Contemporary Peace Research and Practice By Samina Yasmeen | 01 October, 2021

Pakistan: Back to the Future?

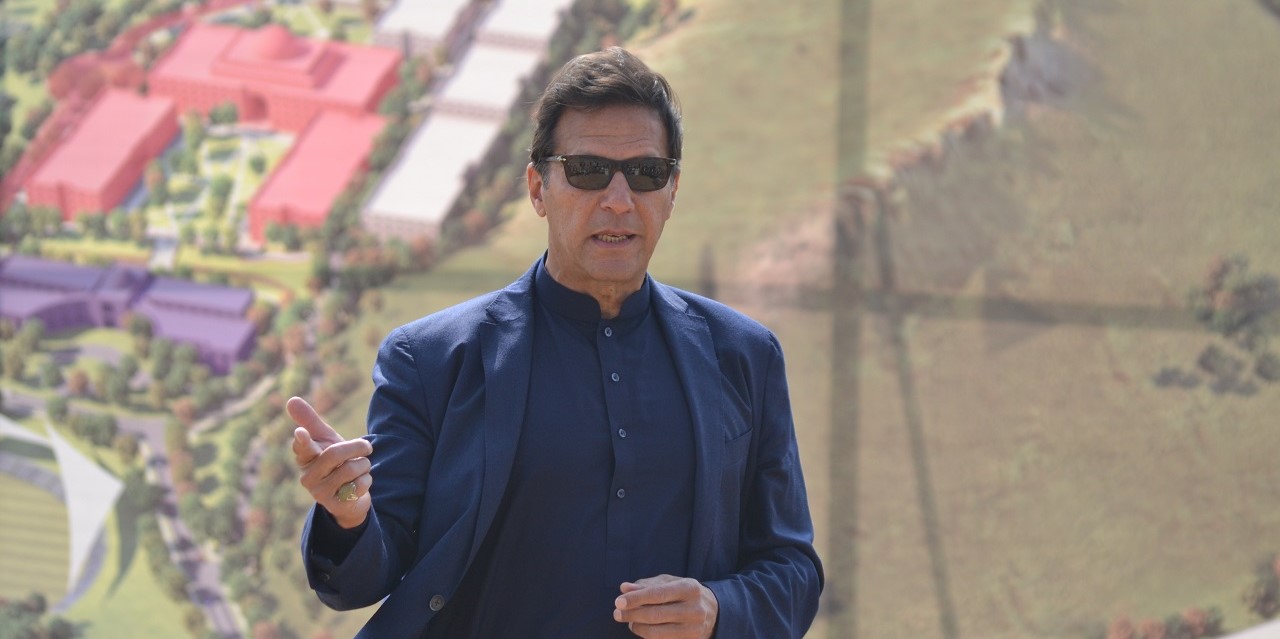

Image: Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan (Irfan Awan, Shutterstock)

After 20 years of American and NATO occupation, the Taliban takeover in Kabul might seem like a return to a pre-9/11 Afghanistan with a Pakistan-supported regime in power. Yet, 20 years on, fundamental differences present significant difficulties for all the powers in the region.

Taliban’s return on 15 August 2021, with seeming lightning speed a fortnight before the planned US withdrawal from Afghanistan, was welcomed euphorically by many in Pakistan. Some groups affiliated with Jamiat-ul-Islam (JUI) distributed sweets in Chaman, a Balochistan-Afghanistan border town. Siraj ul Haq, leader of Jamat-e-Islami (JI), praised the Afghan people for welcoming and opening their doors to the Taliban forces. Pakistan media commentators reminded their audiences of the prophecy of the former ISI Director General, Hameed Gul: “Our ISI has defeated the Russians with the help of the Americans in Afghanistan and now we are going to defeat the Americans with the help of the Americans”. A Gallup survey in mid-September 2021 showed that 55% of the Pakistani respondents viewed Taliban’s return positively.

The Pakistan Government was equally euphoric about the victory of the Taliban and the end of the US occupation of its western neighbours. Prime Minister Imran Khan referred to the success of the Taliban in removing the shackles of mental slavery on the day they occupied Kabul. Three days later, while speaking at the Parliament session about the Taliban’s victory, he reminded his fellow parliamentarians that a commitment to Lá iláha illallah (None has the right to be worshipped but Allah) imbues individuals and nations with ghairat (self-respect and zeal) which results in their success, including the ability to defeat great empires. Meanwhile, his special assistant Raoof Hasan rejoiced at the crumbling of “the contraption that the US had pieced together for Afghanistan …like the proverbial house of cards”. Minister of Human Rights, Shireen Mazari, tweeted images of the US withdrawal from Saigon, Vietnam and Kabul, Afghanistan.

As the US completed its withdrawal and several Western states began evacuating citizens from Afghanistan, the Pakistan Government willingly supported these efforts. It issued visas to those wishing to leave the country via Pakistan and repatriated them on PIA flights within the first few days of the Taliban takeover. Regional states like Saudi Arabia and Turkey hastily sent emissaries to Islamabad to discuss the implications for the new strategic scenario. Together, these developments enabled Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, Shah Mahmood Quraishi, to claim that the world was acknowledging Pakistan as a ‘responsible country’.

Such assertions of good international citizenship are paralleled by analyses of the emerging security complex that assigns Pakistan a pivotal position. While Russia’s significance is acknowledged, Pakistani analysts and policymakers identify China as the country most capable of and willing to support Taliban’s Afghanistan in the post-US withdrawal era. They point to China’s focus on geo-economics and the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership concluded with Iran in March 2021 worth USD 400 billion over the next 25 years. China is also interested in ensuring that economic weakness and fragility does not render Afghanistan a base for terrorists. But most importantly, they see the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) worth US$62 billion (2020) as a major building block of the emerging security complex. Prime Minister Imran Khan’s special advisor, Raoof Hasan, echoed this view when he said:

“[I]n the event this happens, of which there is immense likelihood, the whole region would be connected in an economic corridor linking China with Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and on to Central Asia, Russia and beyond. That would open a world of opportunities for all countries that are linked in this chain which, potentially, could alter the economic and strategic dynamics of the region, turning it into the new mover and shaker of the world.”

Such characterisations of the emerging regional strategic scenario implicitly, and sometimes, explicitly portray India as a loser in the post-US Afghanistan. Siraj-ul-Haq, for example, claimed that Taliban’s return does not simply mean the defeat of the US but also that India has also been defeated. During the last twenty years, many in Pakistan have viewed successive Afghan governments as willing Indian accomplices posing a security threat along their western border. They assert that New Delhi has used Afghanistan as a channel for espionage and to provide support for militant activities, for example, in Balochistan. The return of Taliban is seen as marking an end to this dual-front strategy pursued by India in weakening Pakistan.

Despite such positive assessments of the emerging security complex, the Pakistan Government has responded with a mix of caution and support for the Taliban. This stance is different from the 1990s when Pakistan had hastily recognised the Taliban regime in 1996. Instead, Islamabad has privileged international consensus-building on recognising the Taliban regime and linked it to the idea of an inclusive government that respects human rights, including those of women and minorities, and is committed to not letting its territory be used for terrorism. Imran Khan has also categorically declared, unlike in the 1990s, that it does not view Afghanistan through the prism of strategic depth vis-à-vis India. At the same time, he has urged the international community to extend humanitarian aid to Afghanistan to prevent state failure with the risk of regional and international instability.

The cautious stance is partly linked to Pakistan’s assertion of its identity as a responsible state and good international citizenship. But it is also underpinned by strategic calculations: it is reacting to what it refers to as “scapegoating” and thanklessness by the United States and some other European states. Keen to avoid any justification for reprisals against Pakistan on the assumption that the interim Taliban government is evidence of Islamabad’s influence in Afghanistan and its duplicity, Islamabad has echoed regional and global calls for inclusivity in Afghan political and social policies. India’s position is significant with strengthening US-Indian ties, revitalising the Quad with Indian membership, and is viewed with concern in Islamabad. Pakistan is keen to deny India the possibility of portraying Pakistan as a state committed to supporting terrorism and human rights violations.

Despite the efforts to balance the gains with perceived threats, the Taliban regime will continue to pose a threat to Pakistan’s security. According to the UN Security Council reports, approximately 6,000-6,500 militants have been based in Afghanistan. Attacks in Pakistan by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the largest of these groups, have not subsided. The Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K), with approximately 2000 members, also poses a threat to Pakistan from Afghanistan.

Equally concerning is the emboldening of pro-Taliban groups in Pakistan itself. Since the Taliban’s capture of Kabul, these groups have used social media to stress the value of commitment to ‘true Islamic jihad’ to reshape the region. Some of them are already using it to once again push for the Talibanisation of Pakistani society. Within a week of the Taliban’s return, students raised Taliban flags at Jamia Hafsa in Islamabad, a seminary affiliated with the infamous Lal Masjid (the Red Mosque). Though the flags were removed when demanded by the law enforcement agencies, the incidence does not portend well for stability within Pakistan after the return of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Pakistan appears to be seeking a careful policy balancing the interests of domestic actors with the need to be seen as a responsible international citizen while advocating for immediate and generous humanitarian assistance to prevent Afghanistan from descending into chaos and disorder.

Samina Yasmeen is a teacher and researcher in the University of Western Australia’s School of Social Sciences. Professor Yasmeen is director and founder of the University’s Centre for Muslim States and Societies.