Climate Change and Conflict By Volker Boege | 22 February, 2021

One Loud Voice Needed From The Pacific Islands Forum On Climate Action

Photo credit: Peter Hermes Furian/Shutterstock

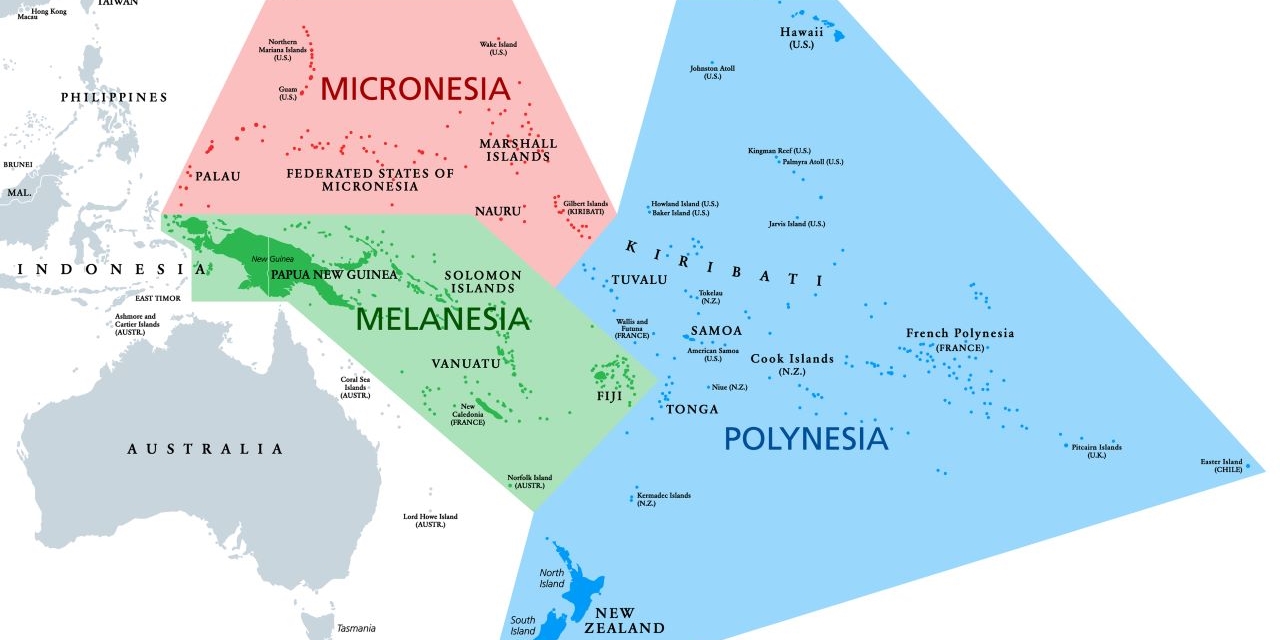

On 3 February, the leaders of the member states of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) came together—online—for a ‘Special Leaders’ Retreat’ in order to appoint a new Secretary General (SG) of the regional organisation to take over from Dame Meg Taylor from Papua New Guinea (PNG), whose second three-year term is coming to an end in April. The former Prime Minister of the Cook Islands, Henry Puna, was appointed as new SG. In a secret ballot he received nine votes, while the second contender, Gerald Zackios, a diplomat from the Marshall Islands, got eight votes. This means that a leader from a Melanesian country will be followed by a leader from a Polynesian country.

Before the meeting, however, the leaders from Micronesia had expressed their view that it was Micronesia’s turn this time, given that the immediate predecessor of Dame Meg Taylor also had been a Polynesian, and given that no Micronesian has held the post for more than twenty years. They referred to an informal unwritten ‘gentlemen’s agreement’: that the post of SG should rotate amongst the three regional groupings that make up the region (Australia and New Zealand are also members of the PIF but do not seek the SG position in normal circumstances).

The leaders of the five Micronesian states—Nauru, the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands and Palau—were deeply disappointed that the ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ was not honoured. After their candidate lost by one vote, they felt gravely wronged. Consequently, at a meeting of the sub-regional Micronesian Presidents’ Summit, the five leaders declared that their countries would leave the PIF.

This declaration came as a shock. The other members of the PIF did not expect such a strong response by their Micronesian partners. If the Micronesian countries follow through on their decision, this will mean a significant split in the regional organisation, which will lose almost a third of its members. This is the most serious challenge to the organisation in its 50-year history. The spirit of regionalism will be seriously weakened, and the weight of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs) in the international arena will diminish.

The Micronesian countries, in particular the Marshall Islands and Kiribati, are extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. For them, global warming is an existential threat. They have been at the forefront of climate action of PICs.

But they are not alone. Melanesian and Polynesian countries are also threatened. Tuvalu, for example, is usually mentioned along with Kiribati and the Marshall Islands as an atoll nation under threat of becoming uninhabitable or even submerged because of climate change-induced sea level rise. And coastal or atoll communities in Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands or Fiji are being forced to relocate due to coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion, floods and inundation.

The ‘sinking islands of the Pacific’ have become a symbol for the severe and unprecedented consequences of man-made global warming. Globally, the PICs are on the radar of politics and public attention first and foremost in the context of climate change. And they showed admirable political talent in utilising this attention in the arena of international climate politics, not just presenting their peoples as ‘victims’ of global warming, but also as a strong moral force in the fight for climate action and climate justice. When PIF member delegates speak at international climate conferences, everybody has to listen. This allows them to punch well above their otherwise limited political weight.

Internally, the climate topic is arguably the most important unifying factor in the Pacific. The PIF’s regional security declaration of September 2018, the Boe Declaration, names climate change as “the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security and wellbeing of the peoples of the Pacific” and promotes “human security” and an “expanded concept of security”.

Globally, the PIF is also at the forefront of linking climate change and peace and security. For example, PIF members have requested that the UN Secretary General appoint a Special Adviser on climate change and security, and that the UN Security Council appoint a Special Rapporteur to elaborate regular reviews of security threats posed by climate change.

In short: The PIF gives voice to those most affected by climate change. It is accepted as a moral leader in the climate debate. This leadership on climate change in the international arena is severely threatened by a split in the PIF.

Not all is lost yet though. The process of actual withdrawal of the five Micronesian states will take a year. This offers a window of opportunity for preventing the break-up. Leaders of several non-Micronesian PIF member states, for example the Prime Ministers of Samoa and PNG, have indicated that they’ll try hard to mend the rift. PNG’s James Marape appealed “for the Micronesian Group to remain with the PIF whilst we collectively work to reform it to ensure all Members’ rights are respected and preserved in the true ‘Pacific Way’”. Meaningful reform of PIF structures is indeed needed. At the Leaders’ Retreat it was agreed that the process of selection of the SG should be reviewed. In fact, it has to be made clear and transparent.

The format of the 3 February meeting, held via zoom rather than face-to-face, was extremely ‘un-Pacific’. Direct personal exchange is of major importance in Pacific cultures. If the leaders had met in person, there would have been more space for ‘Pacific Way’ interactions, and the outcome may have been different. In a Pacific cultural context, decision-making by consensus is clearly preferred to voting, putting ‘majority’ against ‘minority’.

This can be rectified. The regional civil society, which in the Pacific is closely connected across state boundaries—in particular the highly influential churches—, also have a role to play. They can lobby for unity. That the peoples of the Pacific continue to speak with one loud voice when it comes to climate action and climate justice is of utmost importance not only for the PICs themselves, but also for the rest of the world. This voice carries significant weight in the international climate discourse and politics. We desperately need it.

Volker Boege is Toda Peace Institute's Senior Research Fellow for Climate Change and Conflict. Dr. Boege has worked extensively in the areas of peacebuilding and resilience in the Pacific region. He works on post-conflict peacebuilding, hybrid political orders and state formation, non-Western approaches to conflict transformation, environmental degradation and conflict, with a regional focus on Oceania.